Executive Summary

On December 23, 2020, Bella Quinto-Collins called 911, seeking help for her 30-year-old brother, Angelo Quinto, who was agitated and exhibiting signs of a mental health crisis at their home in Antioch, California. When two police officers arrived, they pulled Quinto from his mother’s arms onto the floor. At least twice, Quinto’s mother, Cassandra Quinto-Collins, heard him say to the officers, “Please don’t kill me.” Bella and Cassandra then watched in disbelief and horror as the two officers knelt on Quinto’s back for five minutes until he stopped breathing. Three days later, Quinto died in the hospital.[1]

It was not until August 2021 that the family learned the official determination of cause of death: a forensic pathologist testified during a coroner’s inquest that Quinto died from “excited delirium syndrome.”[2]

Angelo Quinto, a Filipino-American Navy veteran, is one of many people, disproportionately people of color, whose deaths at the hands of police have been attributed to “excited delirium” rather than to the conduct of law enforcement officers. In recent years, others have included Manuel Ellis, Zachary Bear Heels, Elijah McClain, Natasha McKenna, and Daniel Prude.[3] “Excited delirium” even emerged as a defense for the officers who killed George Floyd in 2020.[4]

An Austin-American Statesman investigation into each non-shooting death of a person in police custody in Texas from 2005 to 2017 found that more than one in six of these deaths (of 289 total) were attributed to “excited delirium.”[5] A January 2020 Florida Today report found that of 85 deaths attributed to “excited delirium” by Florida medical examiners since 2010, at least 62 percent involved the use of force by law enforcement.[6] A Berkeley professor of law and bioethics conducted a search of these two news databases and three others from 2010 to 2020 and found that of 166 reported deaths in police custody from possible “excited delirium,” Black people made up 43.3 percent and Black and Latinx people together made up at least 56 percent.[7]

The term “excited delirium” cannot be disentangled from its racist and unscientific origins.

Watch: Debunking “Excited Delirium”

When did the term “excited delirium” evolve to describe a distinct type of “delirium?” How did the corresponding term “excited delirium syndrome” become a go-to diagnosis for medical examiners and coroners to use in explaining deaths in police custody? What is the evidence that it is indeed a valid diagnosis? This report traces the evolution of the term from when it appears to have first been coined in the 1980s to the present. Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) reconstructed the history of the term “excited delirium” through a review of the medical literature, news archives, and deposition transcripts of expert witnesses in wrongful death cases. We evaluated current views and applications of the term through interviews with 20 medical and legal experts on deaths in law enforcement custody. Additionally, we spoke to six experts on severe mental illness and substance use disorders to better understand the context in which the term most often arises. Finally, we interviewed members of two families who lost loved ones to police violence for a firsthand account of the harms of the term’s continued use.

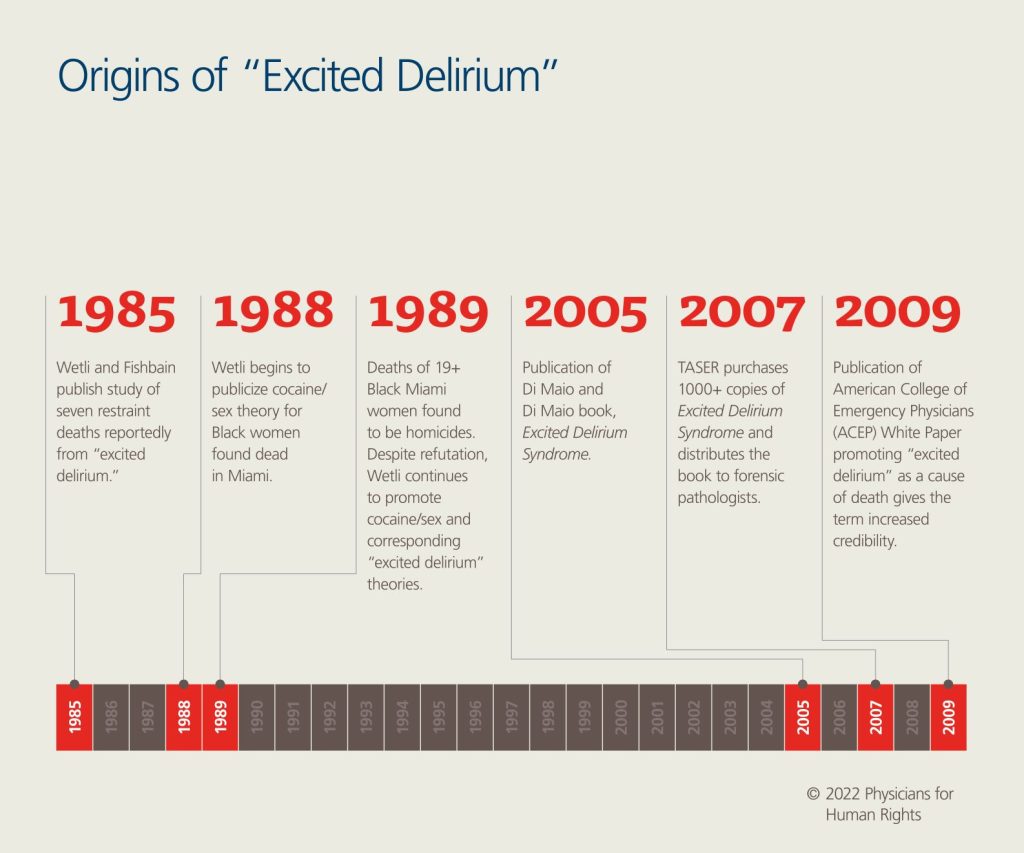

This report concludes that the term “excited delirium” cannot be disentangled from its racist and unscientific origins. Dr. Charles Wetli, who first coined the term with Dr. David Fishbain in case reports on cocaine intoxication in 1981 and 1985,[8] soon after extended his theory to explain how more than 12 Black women in Miami, who were presumed sex workers, died after consuming small amounts of cocaine.[9] “For some reason the male of the species becomes psychotic and the female of the species dies in relation to sex,” he postulated.[10] As to why all the women dying were Black, he further speculated, without any scientific basis, “We might find out that cocaine in combination with a certain (blood) type (more common in blacks) is lethal.”[11]

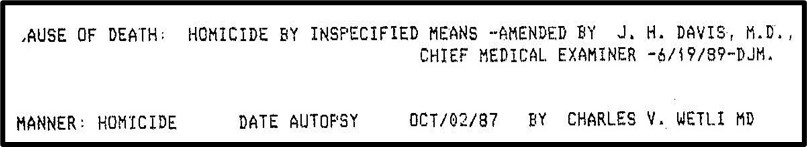

After a 14-year-old girl was found dead in similar circumstances but without any cocaine in her system, Wetli’s supervisor, chief medical examiner Dr. Joseph Davis, reviewed the case files.[12] Davis concluded that all of the women –19 by that point – had actually been murdered, pointing to evidence of asphyxiation in many of the cases.[13] Investigators eventually came to hold a serial killer responsible for the murders of as many as 32 women from 1980 to 1989.[14]

The year after the suspected killer’s arrest, Wetli continued to assert that at least some of the women had died from a combination of sex and cocaine: “I have trouble accepting that you can kill someone without a struggle when they’re on cocaine … cocaine is a stimulant. And these girls were streetwise.”[15] He also continued to promote a corresponding theory of Black male death from cocaine-related delirium, without any scientific basis: “Seventy percent of people dying of coke-induced delirium are black males, even though most users are white. Why? It may be genetic.”[16]

Wetli’s grave mischaracterization of the murders of Black women in Miami – and the racism and misogyny that seemed to inform it – should have discredited his other equally racialized and gendered theory of sudden death from cocaine. Instead, the use of the term “excited delirium” grew.

A small cohort of authors, many working as researchers or legal defense experts for TASER International (now Axon Enterprise) – a U.S. company that produces technology products and weapons, including the “Taser” line of electroshock weapons marketed as so-called “less-lethal” “stun” weapons – increased the broader use of the term by populating the medical literature with articles about “excited delirium.” In 2007, TASER/Axon purchased many copies of a book entitled Excited Delirium Syndrome written by one of its defense experts, Dr. Vincent Di Maio, and his wife Theresa Di Maio, that built on Wetli’s description of “excited delirium” by describing an “excited delirium syndrome.”[17] They distributed the book for free and also gave out other materials on “excited delirium” at conferences of medical examiners and police chiefs.[18] Seven years later, during a deposition, Dr. Di Maio acknowledged that he and his wife had “come up with” the term “excited delirium syndrome.”[19] The term has come to be used as a catch-all for deaths occurring in the context of law enforcement restraint, often coinciding with substance use or mental illness, and disproportionately used to explain the deaths of young Black men in police encounters.[20]

“Excited delirium” is not a valid, independent medical or psychiatric diagnosis. There is no clear or consistent definition, established etiology, or known underlying pathophysiology.

PHR’s review leads to the conclusion that “excited delirium” is not a valid, independent medical or psychiatric diagnosis. There is no clear or consistent definition, established etiology, or known underlying pathophysiology. There are no diagnostic standards, and it is not included as a diagnosis in any version of the International Classification of Diseases, the international standard for reporting diseases and health conditions, currently in its tenth revision (ICD-10), or in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria for psychiatric illness. Neither the American Medical Association nor the American Psychiatric Association currently recognize the validity of the diagnosis. In general, there is a lack of scientific data, and the body of literature supporting the diagnosis is small and of poor quality, with homogenous citations rife with conflicts of interest.

The foundations underpinning the diagnosis of “excited delirium” have been misrepresented, misquoted, and distorted. The ICD-10 and DSM-5 acknowledge delirium and its subtypes as valid, but these do not align with purported criteria for “excited delirium” and are described as stemming from underlying causes. It seems that “excited delirium” as a diagnosis and standalone cause of death was originally brought about by one or a few people’s subjective opinions. The term has since taken on a meaning and life of its own, with a deleterious impact.

In our interviews with clinicians and scientists across disciplines, there was no consensus on the definition of “excited delirium.” A review of the medical literature further confirms that the syndrome is not well defined or understood. The term is therefore scientifically meaningless because of this lack of consensus or rigorous evidentiary basis. Many of the studies that have been used to support the diagnosis have serious methodological deficiencies and are laden with conflicts of interest with law enforcement and TASER/Axon. Moreover, the use of “excited delirium” to explain agitated behavior raises the concern that underlying causes of these behaviors, such as a mental illness or substance intoxication, are not being diagnosed or treated. Most significantly, it is disturbing that “excited delirium” as a diagnosis has been used to justify aggressive and even fatal police tactics.

It is also concerning that “excited delirium” has come to pervade law enforcement policies and training manuals, at least in part due to the continued acceptance of the term by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) and National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME). Officers in many law enforcement agencies are trained to respond to an array of medical emergencies as “excited delirium,” which in practice have included conditions that may not all warrant the same medical response, including heart attacks, drug or substance overdoses or withdrawals, acute psychosis, and oxygen deprivation. “Excited delirium” has also gained international reach, having received attention in the wake of in-custody deaths in Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, among other countries.[21]

The diagnosis of “excited delirium” has come to rest on racist tropes of Black men and other people of color as having “superhuman strength” and being “impervious to pain,” while pathologizing resistance to law enforcement, which may be an expected or unsurprising reaction of a scared or ill individual (or anyone who is being restrained in a position that inhibits breathing). Presently, there is no rigorous scientific research that examines prevalence of death for people with “excited delirium” who are not physically restrained.

The term has come to be used as a catch-all for deaths occurring in the context of law enforcement restraint … and disproportionately used to explain the deaths of young Black men in police encounters.

People who present with symptoms and signs such as agitation, confusion, fear, hyperactivity, acute psychosis, sweats, noncompliance with directions, tachycardia (rapid heart rate), and tachypnea (rapid breathing), which are too often classified by medical examiners and coroners as “excited delirium,” must be recognized as having an underlying diagnosis. The specific underlying condition should be identified and treated. Too often, law enforcement officers are called as the sole first responders to medical emergencies and then use violent methods to forcibly restrain people manifesting these signs, methods – such as those that induce asphyxia from prone and other forms of restraint – that themselves may cause death. Consequently, “excited delirium,” rather than law enforcement actions, is cited as the cause of death, or as a factor contributing to death, in autopsy reports.

PHR holds that “excited delirium” is a descriptive term of a myriad of symptoms and signs, not a medical diagnosis, and, as such, should not be cited as a cause of death. It is essential to end the use of “excited delirium” as an officially determined cause of death, particularly in cases of deaths in police custody. This is one critical step among many to stop these preventable deaths.

Introduction

As Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on George Floyd’s neck in May 2020, fellow officer Thomas Lane said, “Roll him on his side?… I just worry about the excited delirium or whatever.” Officer Lane’s comment in the midst of George Floyd’s murder is indicative of the extent to which the concept of “excited delirium” has come to pervade U.S. law enforcement training and practice.

This report traces how “excited delirium” has evolved from a description in case reports of people with cocaine intoxication into a term that is used by law enforcement, forensic pathologists, emergency physicians, and in courts. Others have already described the troubled history of “excited delirium.”[22] Yet since the term persists, this report reviews the origins, history, medical literature, and views of experts and affected family members in order to evaluate the underlying validity of the diagnosis.

It is essential to cease the use of “excited delirium” as an officially determined cause of death, particularly in cases of deaths in police custody. This is one critical step among many to stop these preventable deaths.

Background

In the United States, people of color are far more likely than white people to be killed by police.[23] The American Medical Association, American Public Health Association, National Medical Association, and many other groups recognize this as a public health crisis.[24] In addition, a significant percentage of police killings – anywhere from 25 to 50 percent – occur while responding to mental health, behavioral health, or substance use disorder crises.[25]

The in-custody killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in May 2020 ignited an unprecedented wave of national and global demonstrations in support of the Black Lives Matter movement and against police brutality and systemic racism across many areas of law enforcement. Protesters called for accountability for police killings and reforms, with many urging the reallocation of funding from law enforcement to social and community services, including mental health services. Protesters also drew attention to the ways in which certain health emergencies all too often receive a law enforcement rather than a medical response, which can result in serious harm or death.

In Many Areas, the United States Lacks Appropriate Systems to Respond to Mental and Behavioral Health Crises

In 2020, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), a branch of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, reported that more than one in every five American adults (21 percent) experienced a mental illness.[26] Additionally, in 2020, more than one in every 20 adults (5.6 percent) experienced a serious mental health condition, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.[27] Both of these estimates were higher than annual estimates from 2008 through 2019.[28]

Despite the increasing prevalence of mental health conditions in the United States, there remains a lack of appropriate emergency response systems for people in crisis. Moreover, the deinstitutionalization movement, beginning in the 1950s, left many people with severe mental illness with neither proper treatment nor resources. This has led to a number of people finding themselves homeless or in contact with the carceral system rather than appropriate treatment.[29] The norm when someone is experiencing a mental health crisis is to call emergency services through 911, where, in most jurisdictions, the police often respond. Using armed police as first responders in these cases can result in an escalation of the situation while criminalizing or further endangering the person in crisis. Introducing people with mental illness in crisis first to the carceral system by proxy of a police officer, instead of a trained mental health counselor or clinician, can and has led to deaths at the hands of law enforcement.[30] A 2015 report by the Treatment Advocacy Center found that people with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed during a law enforcement encounter than other civilians.[31]

A significant percentage of police killings – anywhere from 25 to 50 percent – occur while responding to mental health, behavioral health, or substance use disorder crises.

In a 2021 report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) observed that law enforcement officers frequently violate the rights of Black people experiencing mental health crises to protection from discrimination on the basis of both race and disability. OHCHR reviewed more than 190 reports of deaths of Black people in law enforcement custody worldwide, including in the United States, finding that one of the three contexts that accounted for 85 percent of the cases that occurred was “the intervention of law enforcement officials as first responders in mental health crises.” The report stated:

“Several incidents analyzed by OHCHR occurred after calls to emergency services seeking assistance for a person experiencing a mental health crisis. According to the analysis, when acting as first responders, police interventions often aggravate the situation including due to the use of restraints, while crises de-escalation protocols may not provide for appropriate crisis support services. Further, police often fail to identify the victims as individuals in distress and in need of rights-based mental health support. Instead, racial bias and stereotypes compounded with disability-based stereotypes appear to lead law enforcement officials to perceive the victim as “dangerous”, overriding considerations of the individual’s safety and well-being and of delivery of the appropriate care and basic life support.”[32]

“When you’re dealing with severe mental illness, and especially when you’re a Black family or a brown family, you pause before you call the police.”

Sabah Muhammad, attorney and legislative and policy counsel, Treatment Advocacy Center

Standards for Death Investigations in the United States Vary by Jurisdiction

In the United States, official processes for investigating and establishing cause of death vary by state and local jurisdiction. Each state has different requirements for which kinds of deaths require investigations or autopsies.[33] Death investigation systems are highly variable, including both medical examiner systems and coroner systems. In most systems, it is a coroner or medical examiner’s responsibility to lead an investigation to determine the circumstances of a person’s death in cases of homicide or when there is suspicion of crime or foul play, including police violence.[34] Coroners in most states do not have to be physicians.[35] Medical examiners are physicians but are not always forensic pathologists. Forensic pathologists are physicians that specialize in pathology (study of injured organs, tissues, and cells) and work at the intersection of law and medicine to determine the cause of death. Twenty-three (23) states and Washington, D.C. have appointed medical examiner and/or coroner systems, 11 states have elected coroners and appointed medical examiners, four states have a combination of elected and appointed coroners, and 12 states have a combination of elected and appointed medical examiners.[36]Although there is a lack of national standards and of a universal definition, the consensus for defining deaths in custody is “deaths of persons who have been arrested or otherwise detained” by law enforcement officials.[37]

In 2009, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) recommended, “Congress should authorize and appropriate incentive funds to the National Institute of Forensic Science (NIFS) for allocation to states and jurisdictions to establish medical examiner systems, with the goal of replacing and eventually eliminating existing coroner systems.” NAS further held, “All medicolegal autopsies should be performed or supervised by a board certified forensic pathologist.”[38]

Law Enforcement-Related Deaths Are Under-Counted

There is strong evidence that deaths after or during interaction with law enforcement are not always appropriately reported, monitored, or investigated. A 2017 Harvard study found that more than half of all police killings in 2015 were incorrectly classified as not the result of police officer interactions.[39] Coroners and medical examiners were found to regularly report results that minimized the accountability of police officers.[40] The study compared data from The Guardian’s “The Counted,”[41] an investigative project on police killings, to data from the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), a U.S. federal government system that gathers death certificate data, identifies law enforcement-related deaths, and assigns a corresponding diagnostic code: “legal intervention.”[42] This same study found that there were significantly more law enforcement-related deaths in The Guardian’s data set compared to the NVSS. They further discovered that the NVSS had misclassified 55.2 percent of all police killings, and that deaths in low-income areas were disproportionately underreported.[43]

A 2021 study found that the National Vital Statistics System, the most comprehensive mortality database in the United States, failed to report “55.5 percent of all deaths attributable to police violence,” missing about 17,100 deaths from 1980 to 2019.

Similarly, a 2021 Lancet study compared data from the NVSS to “The Counted” and two other media-based databases on police violence, “Fatal Encounters” and “Mapping Police Violence.” The results showed that the NVSS failed to report “55.5 percent of all deaths attributable to police violence,” missing about 17,100 deaths from 1980 to 2019.[44] The study also found that the age-adjusted mortality rate due to police violence grew by 38.4 percent from the 1980s to the 2000s, and mortality rates due to police violence were highest in non-Hispanic Black people, followed by Hispanic people of any race, non-Hispanic white people, and finally non-Hispanic people of other races.[45]

System Flaws and the Ability to Manipulate the Reporting System Contribute to Under-Counting of Law Enforcement-Related Deaths

Several factors contribute to under-counting of law enforcement-related deaths. One oft-cited reason is the lack of independence of coroners and medical examiners. In a 2011 survey of National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME) members, 22 percent reported experiencing political pressure from elected or appointed officials to change the cause or manner of death listed on death certificates.[46] Conflicts of interest built into many systems include having medical examiners and coroners work for or be part of police departments.[47] A second contributor to under-counting is the lack of well-established standards and guidelines. There are no standards or explicit instructions to note whether there was police involvement in many death certificates’ open-ended sections to “describe how the injury occurred,” or to assure correct coding that there was law enforcement involvement, even if the certificate notes police involvement. Moreover, lack of standards to ensure sufficient knowledge and training of coroners and medical examiners further contributes to errors in classification. For example, some medical examiners face difficulty in having to determine whether a restraint case, such as a “hog-tying incident,” should be classified as “homicide,” “accident,” or “undetermined.” There is no national definition on manner of death for these police custody killings.[48] Lastly, fear of litigation resulting from problematic conduct also influences accurate documentation. In another NAME survey with 222 medical examiner respondents, 13.5 percent acknowledged modifying their forensic findings because of previous threats of litigation, and approximately 32.5 percent revealed that these considerations would impact their decisions in the future.[49] Thirty (30) percent expressed that “fear of litigation affected their diagnostic decision-making.”[50] In this way, a lack of standards is compounded by a lack of independence of forensic scientists to act without undue pressure from law enforcement or political officials.

In 2002, the National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME) published its first edition guide for manner of death classification; it notes that its guide is not a standard and that death certification requires judgment on a case-by-case basis.[51] It elaborates that manner of death (i.e., determination of how an injury or disease leads to death, such as natural, accident, suicide, homicide, or undetermined) is “circumstance-dependent, not autopsy-dependent.”[52] This guide outlines important general principles and definitions:

“Natural deaths are due solely or nearly totally to disease and/or the aging process. Accident applies when an injury or poisoning causes death and there is little or no evidence that the injury or poisoning occurred with intent to harm or cause death. Homicide occurs when death results from a volitional act committed by another person to cause fear, harm, or death. Intent to cause death is a common element but is not required for classification as homicide…. Undetermined or “could not be determined” is a classification used when the information pointing to one manner of death is no more compelling than one or more other competing manners of death in thorough consideration of all available information. In general, when death involves a combination of natural processes and external factors such as injury or poisoning, preference is given to the non-natural manner of death.”

The “but-for” logic is often used as a simple way to determine whether a death should be classified as natural or non-natural.[53] “But-for the injury (or hostile environment), would the person have died when [they] did?” The guide elaborates that “the manner of death is unnatural when injury hastened the death of one already vulnerable to significant or even life-threatening disease.” In this guide, the authors call for greater national consistency in death certification.

In 2017, NAME published a position paper with recommendations for the investigation and reporting of deaths in police custody. In summary, the association calls for an investigation into the facts and circumstances of these deaths, and notes that the investigation has the potential to prevent similar future deaths and provide educational benefits.[54] The report elaborates on cause of death and manner of death:

“This committee recommends that the physician consider homicide as the manner of death in cases similar to those that would otherwise meet the threshold of ‘death at the hands of another.’ While the cause and manner of death designation should be handled the same as any other, the certifying physician/professional should fully utilize the ‘How Injury Occurred’ section of the death certificate to communicate that the death occurred in custody. For example, wording such as ‘Shot by Law Enforcement’, ‘Driver of Motor Vehicle in Collision with Fixed Object during Pursuit by Law Enforcement’, ‘Shot Self in the Presence of Law Enforcement’, ‘Hanged Self while Incarcerated’, or ‘During Restraint by Law Enforcement’ should be included.”

Methodology

Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) sought to understand the complex origins, history, current usage, and validity of “excited delirium” by pursuing multiple strands of inquiry.

Documents

As part of PHR’s work to systematically document the origins, history, and evolution of the term and concept of “excited delirium,” PHR partnered with civil rights attorney Julia Sherwin, who, through nearly two decades of work, has compiled an extensive library of news archives, deposition transcripts, court documents, and articles related to the origins and history of “excited delirium.” PHR obtained additional deposition transcripts and court documents from civil rights attorneys John Burton and Ben Nisenbaum.

Medical Literature Review

To examine the extent and quality of evidence for “excited delirium” as a diagnosis and potential cause of death, physician members of the PHR team conducted a scoping review of and analyzed peer-reviewed medical literature.[55] On August 19, 2021, PHR conducted a PubMed/MEDLINE search using the key words “excited delirium” without filters. Two hundred twenty-six abstracts (226) were found between the available date range of January 1956 and August 2021. Titles and abstracts were screened for information on diagnostic criteria for “excited delirium,” origins of the term, pathophysiology, and evidence for the syndrome. If the abstract was not available or if the article was unclear after a review of the abstract alone, a full review of the article was performed.

Articles were excluded if they were not peer reviewed, not in English (due to a lack of capacity to translate), or did not provide any of the following: 1) historical information on the origins of “excited delirium;” 2) a definition or description of “excited delirium,” which may have included pathology or pathophysiology; or 3) a discussion of evidence for or against “excited delirium” as a distinct syndrome. Articles were also excluded if they focused solely on a case report or series, drugs, or treatment without significant discussion of “excited delirium” as an entity itself. Of the 226 articles, 180 did not meet the above criteria and were excluded from our analysis, leaving 46 peer-reviewed articles. A secondary search was performed on the same database using the term “excited delirium syndrome,” which yielded 95 results, all of which had already been captured in the primary search. (Of note, alternate search terms were not employed, such as “Bell’s mania,” “agitated delirium,” “positional asphyxia,” “restraint asphyxia,” “in-custody deaths,” or “police use of force.”)

Between August 19, 2021 and October 20, 2021, PHR team members read and abstracted articles that met inclusion criteria. To provide important context to the 46 peer-reviewed articles, other literature, such as letters to the editor and commentary, secondary references, consensus and position papers, and non-peer reviewed material, were also considered and incorporated in this report when germane.

To check for saturation and consistency, results were compared to a general literature review performed in July 2021 by a different PHR team during the concept design stage of this report. The references and conclusions of these two independent literature reviews were complementary and consistent.

Interviews

In light of the continued use of “excited delirium” as a cause of death among medical examiners and coroners, PHR explored the experiences and perspectives of forensic pathologists and other medical and legal experts on deaths in custody. After obtaining exemption from PHR’s Ethics Review Board, given the low risk to interviewees, PHR conducted individual semi-structured interviews with 20 experts on deaths in police custody regarding their knowledge and perspective on the use of “excited delirium” as a cause of death. The interviewees included nine forensic pathologists (across the United States, Canada, Chile, and New Zealand, one of whom also trained in Italy and Scotland), one forensic epidemiologist, two emergency physicians, one surgeon who is also a certified medico-legal death investigator, four plaintiff’s attorneys, two prosecutors, and one law enforcement trainer.[56] We used snowball sampling to connect with experts and continued reaching out to prospective interviewees until we reached thematic saturation (i.e., no new themes emerged during analysis of interview transcripts). Although the focus of our research was the use of “excited delirium” as a cause of death in the United States, we also interviewed forensic pathologists based outside the United States considering the global reach of the medical literature on “excited delirium.”

In the interviews with physicians, we sought to identify areas of consensus and ongoing discussion regarding “excited delirium” and to learn about their introduction to the term and the evolution of their understanding. We interviewed the attorneys to inform the report background and to seek their views on the prevention of deaths in custody that are attributed to “excited delirium.” PHR also held conversations geared toward preventing such deaths with experts on mental health and substance use crisis response, including staff at the Treatment Advocacy Center, National Harm Reduction Coalition, Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS), and Portland Street Response.[57]

Finally, PHR received approval from PHR’s Ethics Review Board to interview members of families who had lost loved ones to deaths in police custody in the United States where “excited delirium” was designated by medical examiners as the cause of death. We connected with civil rights attorneys who represent families in wrongful death lawsuits against law enforcement officers and asked the attorneys whether any of their clients were interested in speaking with us for our report. Two families conveyed through their attorneys their interest in speaking with PHR, and their attorneys were present for the subsequent interviews.

All interviews took place via video or audio conferencing due to the SARS-CoV-2 public health emergency and wide geographical location of interviewees. All participants gave verbal consent to the interview, and for the interview to be recorded. Notes were also typed during the interviews.

Interviewees were informed of the purpose and voluntary nature of the interview. They were told that they could stop the interview at any time and that all possible measures would be taken to keep their identity confidential unless they wanted to disclose it. They were given the option of remaining anonymous and using a pseudonym in this report. Interviewees received no compensation for participating in interviews. The interviewers used an interview guide, previously agreed upon by the research team. Interview materials and transcripts were stored securely on PHR computers. Team members reviewed the written notes and transcripts to identify key themes across the interviews and pull illustrative quotes.

Limitations

PHR’s interviews with forensic pathologists, emergency physicians, lawyers, and others are not intended to be a representative sample of the field. Rather, we sought to speak to experts both in the United States and internationally to gauge areas of consensus and ongoing discussion regarding the continued use of “excited delirium.”

The medical literature review was not exhaustive and used one biomedical literature database (PubMed/MEDLINE). Only “excited delirium” and “excited delirium syndrome” were searched and may have not resulted in a comprehensive selection of relevant articles. After articles meeting inclusion criteria were identified and reviewed, a pragmatic research approach was adopted: references of included articles were explored for context and history.

Findings

Origins and History

Key Definitions

A syndrome consists of a group of signs and symptoms that occur together and characterize a discrete abnormality or condition.[58] The cause, pathophysiology, and/or course of a “syndrome” is often not clearly understood. Once medical science identifies a clear causative agent or underlying pathophysiologic process, the group of signs and symptoms are then referred to as a “disease.” What are considered diseases change over time as a result of advances in technology, diagnostic ability, and expert consensus determinations, among other factors. In psychiatry, maladaptive mental and behavioral disturbances that impair functioning are often referred to as disorders. There are well-defined criteria for diagnosing psychiatric disorders, even though some have criticized these criteria as unreliable.[59]

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) defines delirium as a neurocognitive disorder characterized by a “disturbance in attention and awareness that develops over a short period of time and is not better explained by another preexisting, evolving, or established disorder.”[60] Additional features may include hypo- or hyperactivity and emotional disturbances such as fear, agitation, or euphoria, as well as reduced awareness of the environment. The pathophysiology of delirium is poorly understood, but it is generally accepted as a sign of an underlying disease process, such as organ failure, infection, lack of oxygen, metabolic imbalance such as low blood sugar levels, drug side effects, intoxication, or withdrawal, among others. Delirium is medically treated by finding and treating the underlying cause, along with supportive behavioral modifications and medical care such as hydration, psychopharmaceuticals, and pain control.

Restraints in the medical context are actively discouraged and avoided in the management of delirium, never include prone or neck restraints, and are monitored by an independent medical oversight organization (the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations). Delirium is not itself considered a cause of sudden death.

Bell’s Mania

In 1849, Dr. Luther Bell, a Massachusetts physician at the McLean Asylum for the Insane, described cases of primarily female psychiatric patients who experienced symptoms and signs such as overactivity, delusions, transient hallucinations, sleeplessness, and fevers, typically over days to weeks, and in some cases resulting in death.[61] This constellation of signs and symptoms has been called Bell’s Mania, delirious mania, acute maniacal delirium, lethal catatonia, and, later, chronic “excited delirium.”[62] The Bell’s Mania description occurred long before other diagnoses like schizophrenia,[63] bipolar mania, or autoimmune encephalitis were described in their current formulations, and the signs and symptoms of Bell’s Mania are consistent with these diagnoses, among others. The disappearance of case reports using these descriptions between the 1950s and 1980s has been attributed to the rise of relatively effective antipsychotic medications and treatment and greater psychiatric diagnostic precision.[64]

Wetli and Fishbain

The introduction of the term “excited delirium” in the 1980s has been attributed to Drs. David Fishbain and Charles Wetli. In the early 1980s, at the University of Miami, Fishbain was director of psychiatric emergency services, and Wetli was a forensic pathologist. In 1981, Wetli and Fishbain co-authored a case report of cocaine intoxication in a person who swallowed packets of cocaine in order to store them within their body, termed “bodypacker.”[65] Wetli and Fishbain described the resulting delirium as a medical emergency characterized by a disturbance of attention with impaired perception. They characterized this “acute excited delirium” as reversible, transient, and with an array of possible causes. They elaborated that there are “two types of delirium: stuporous … and excited.” Notably, they stated that the treatment of delirium is of the underlying illness and concluded that the delirium presentation hides the “medical nature.”

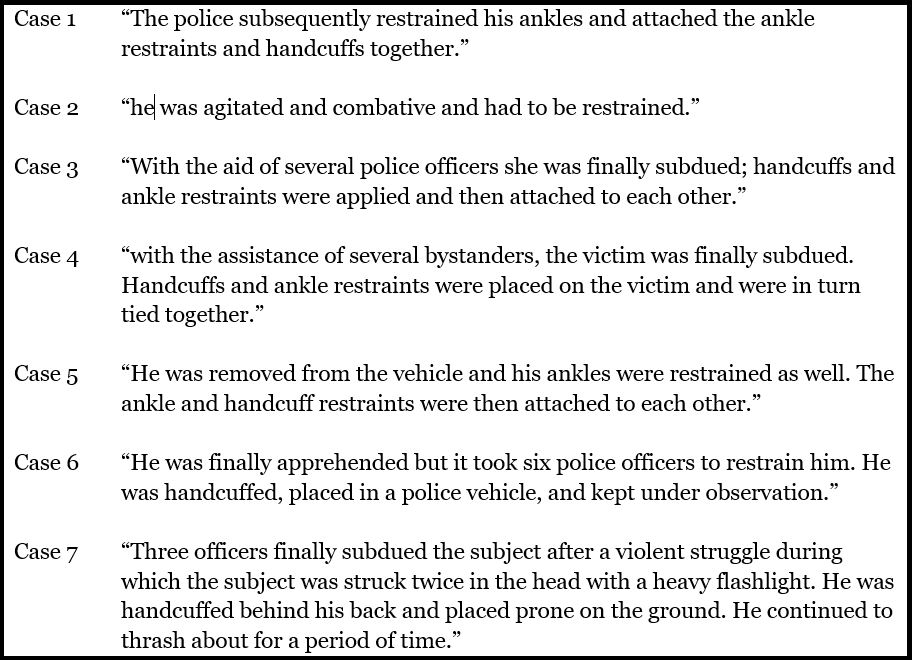

In 1985, Wetli and Fishbain published a case series on cocaine-induced psychosis.[66] This series described seven cocaine users (six men and one woman) who exhibited fear, panic, violent behavior, hyperactivity, hyperthermia, and/or unexpected strength. All of them had been restrained (six by police, in some cases with the assistance of bystanders, and one by emergency room staff) and all died suddenly with respiratory arrest, with five of them reportedly dying in police custody.

Autopsies did not reveal any “anatomic cause of death.” In this publication, Wetli and Fishbain again described “excited delirium” as a “medical emergency but with a psychiatric presentation” and noted that the “prognosis depends on the underlying cause of the delirium.”

Four of the seven people had been either hog-tied (had their hands and feet fastened together) or put into a hobble restraint (a nylon strip that ties a person’s ankles together and links them to their wrists handcuffed behind their back) in a prone position, which can impair breathing. Other than mentioning the prone restraint in passing, Wetli and Fishbain did not discuss the role restraint may have played in these victims’ deaths.

In both these 1981 and 1985 case reports, Wetli and Fishbain reference the Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 3rd edition, chapter 20, pages 1359–1392.[67] This section was written by Dr. Zbigniew J. Lipowski. (PHR obtained the same edition and reviewed these pages.) Wetli and Fishbain cite Lipowski when defining delirium, including the description of a hyperactive and hypoactive delirium: “There are two major types of delirium: stuporous (dull, lethargic, hypoactive, mute, somnolent, and apathetic), and excited (thrashing, shouting, hyperactive, fearful, panicky, agitated, hypervigilant, and violent).”[68] Lipowski does not use the term “excited delirium.” It is our conclusion that Wetli and Fishbain initially used “excited” as an adjective to portray the hyperactive form of delirium.

A short time later, Wetli, as will be discussed below, began using “excited delirium” as a cause of death, diagnosis, and unique disease. There is, however, no indication in his writings that he had access to new scientific evidence underpinning this change.

Serial Murders of Black Women in Miami

In the years that followed his publications on cocaine-induced “excited delirium,” Wetli began to seek new applications of his theories in his work as deputy chief medical examiner in Miami.

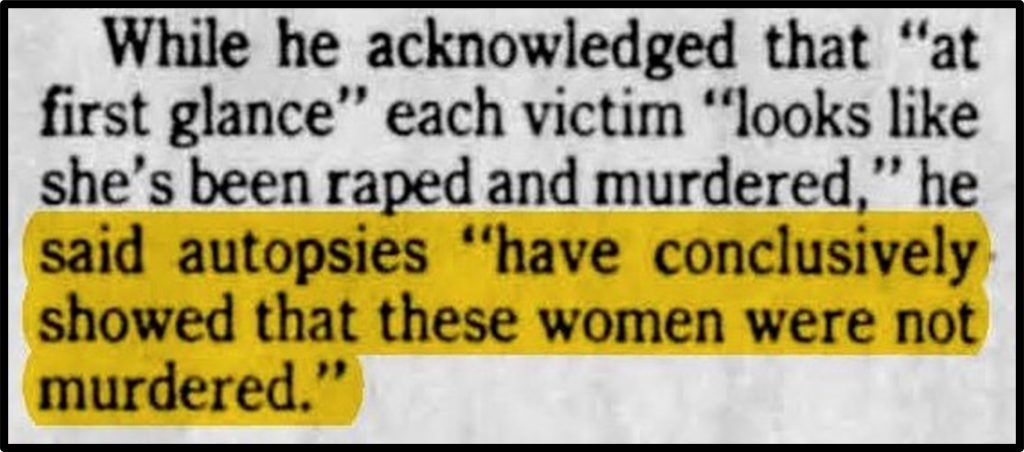

Between September 1986 and November 1988, 12 Black women who were presumed sex workers were found dead, one after the other, in the same geographic area of Miami.[69] Wetli and several of his colleagues found that almost all had low levels of cocaine in their systems and classified the majority of the deaths as accidents from cocaine intoxication.[70] On November 24, 1988, Wetli began to publicize his theory that the women had died from combining sex with cocaine use, claiming that autopsies had “conclusively” shown they had not been murdered.[71]

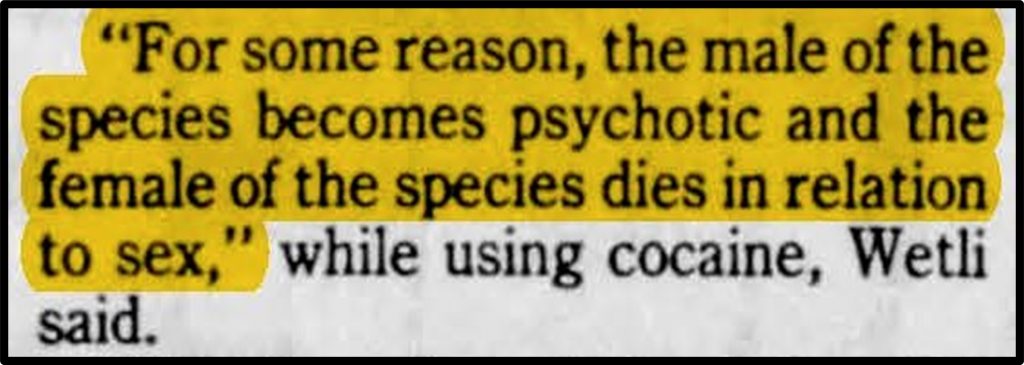

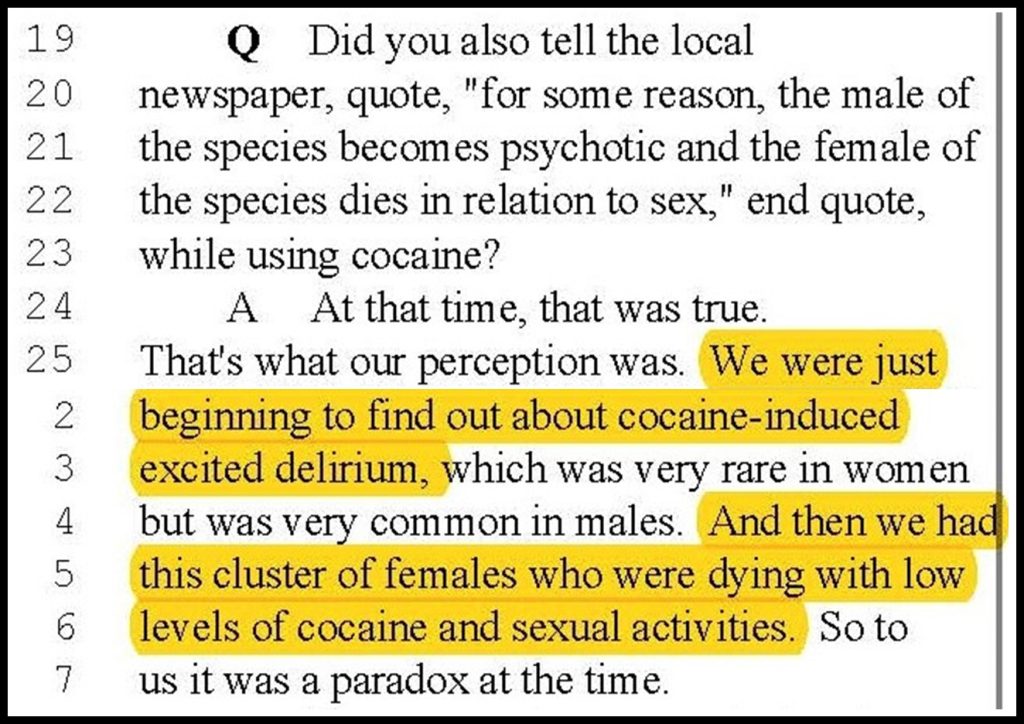

Wetli speculated that while the women were working as sex workers, they consumed small amounts of cocaine and then died from sexual excitement, which he described as the female manifestation of the “cocaine psychosis” he had previously identified in men.[72] “For some reason, the male of the species becomes psychotic and the female of the species dies in relation to sex,” he said.[73]

As to why all the women dying were Black, he further speculated, without any scientific basis, “We might find out that cocaine in combination with a certain (blood) type (more common in blacks) is lethal.”[74]

The following month, he said, “We know that the deaths are related to crack, but we still don’t know the mechanism.”[75]

On December 12, 1988 – less than a month after Wetli began to publicize this theory – 14-year-old Antoinette Burns was found dead.[76] Wetli, who performed the initial autopsy, believed that she, too, had died from a combination of sex and cocaine use.[77] For weeks, Burns’ family pushed back against this theory, but it was not until the toxicology report came back negative that authorities began to take them seriously.[78]

In March of 1989, police investigators confronted Wetli’s supervisor, chief medical examiner Dr. Joseph Davis, with evidence they believed pointed to homicide.[79] Davis began to reexamine the case files.[80] In May, a newsweekly reported that the number of Black women found dead had reached at least 17.[81] The article noted that Burns had died without cocaine in her system and cited investigators’ beliefs that a serial killer was actually responsible for the women’s deaths.[82] Burns’ mother told the paper, “I’m always wondering who killed her and how did she die. I want justice to be served.”[83]

The article described Wetli’s sex-cocaine theory for women as the counterpart of his “excited delirium” theory about men. “The women may be dying after sexual activity,” Wetli said. “The men just go berserk.”

Wetli, meanwhile, continued to promote his theory that cocaine combined with orgasm produced lethal results: “We still really don’t know what’s going on. My gut feeling, though, is that this is a terminal event that follows chronic use of crack cocaine affecting the nerve receptors in the brain. I think it’s a type of neural exhaustion.”[84] The article described Wetli’s sex-cocaine theory for women as the counterpart of his “excited delirium” theory about men. “The women may be dying after sexual activity,” Wetli said. “The men just go berserk.”[85]

Later that month, Davis announced his conclusion that the deaths of all of the women – 19 by that point – were homicides.[86] He reclassified the 14 that had initially been ruled accidents or left unclassified.[87] Only nine women’s bodies had been found soon enough to identify concrete signs of strangulation and/or asphyxiation.[88] In those women’s cases, Davis found evidence of neck pressure in seven and pressure to the mouth in four, as well as evidence of hemorrhaging in the eyes.[89] He noted that in some of the women’s cases, the signs of asphyxiation were so pronounced that one could see them from “ten feet away, it’s that clear.”[90]

All but one of the women were believed to have the same killer.[91] Police soon identified Charles Henry Williams, a convicted rapist, as the primary suspect.[92] Arrested in 1989 on an unrelated rape charge, he was eventually believed to be responsible for the deaths of as many as 32 women since 1980.[93] Later charged with one of the murders, he died before he could stand trial.[94]

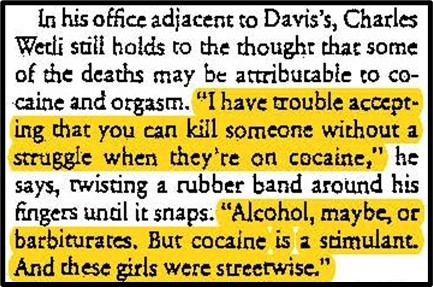

One year after Davis’s reclassification of the deaths as homicides, Wetli continued to assert that at least some of the women had died from a combination of sex and cocaine: “I have trouble accepting that you can kill someone without a struggle when they’re on cocaine … cocaine is a stimulant. And these girls were streetwise.”[95]

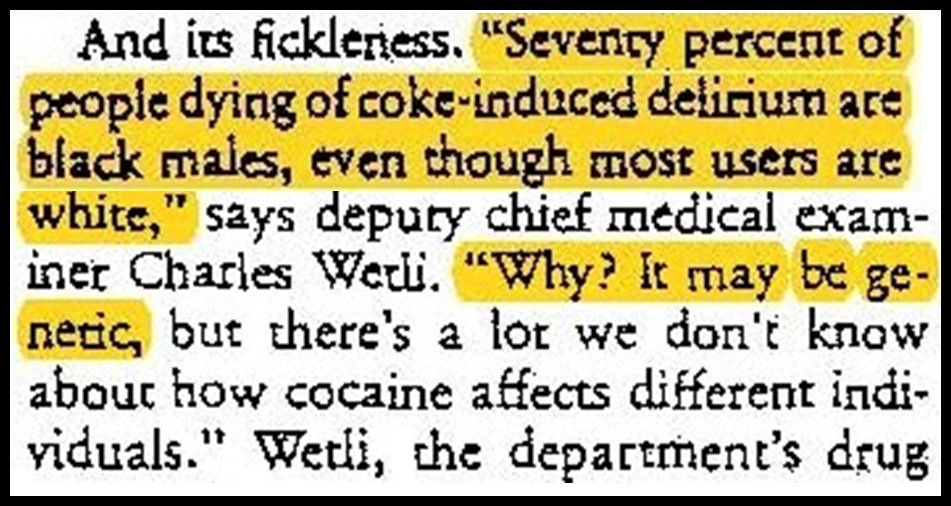

Wetli also continued to promote a corresponding theory of Black male death from cocaine-related delirium, without any scientific basis: “Seventy percent of people dying of coke-induced delirium are black males, even though most users are white. Why? It may be genetic.” [96]

Wetli’s grave mischaracterization of the murders of Black women in Miami – and the racism and misogyny that seemed to inform it – failed to discredit his other equally racialized and gendered theory of sudden death from cocaine.[97] Instead, the use of the term “excited delirium” grew.

NAME Position Paper (2004)

More than a decade later, Wetli coauthored a 2004 National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME) position paper that continued to link cocaine use to “excited delirium.”[98] That position paper, in a single reference, noted briefly “a catecholamine-mediated excited delirium, similar to cocaine” that was “becoming increasingly recognized and has been detected in patients with mental disorders taking antidepressant medications, and in psychotic patients who have stopped taking their medications.” It provided as a citation for this claim the abstract of a presentation by Wetli.[99] Yet, in discussing “sudden death related to police actions,” the paper only discussed assessing the involvement of cocaine as a cause of death and asserted that “other obvious causes of death must be carefully ruled out through a careful scene investigation, meticulous forensic autopsy, and a review of the medical information.” The paper also delineated criteria for a diagnosis of “cocaine-induced excited delirium,” requiring a “clinical history of chronic cocaine use, typically bizarre and violent psychotic behavior, and the presence of cocaine or its metabolites in body fluids or tissues.” It did not discuss at all criteria for diagnosing “excited delirium” from causes other than cocaine use.[100]

In its 2017 position paper on recommendations for the investigation and reporting of deaths in police custody, NAME referenced “excited delirium” in passing, noting, “the more difficult cases are those where the individual is observed to be acting erratically due to a severe mental illness and/or acute drug intoxication. These cases have been defined in the literature as excited delirium and often result in a law enforcement response and restraint of the decedent.”[101]

Publication of Excited Delirium Syndrome

In 2005, Theresa Di Maio, a psychiatric nurse, and her husband, Dr. Vincent Di Maio, a forensic pathologist who was serving as the chief medical examiner of Bexar County, Texas and editor of the American Journal of Medicine and Pathology, published a book on “excited delirium syndrome.”[102] They defined the term as “the sudden death of an individual during or following an episode of excited delirium, in which an autopsy fails to … explain the death.”[103] They defined “excited delirium” as “delirium involving combative or violent behavior” caused by “normal physiologic reactions of the body to stress gone awry.”[104] The Di Maios discussed the history and origins of “excited delirium” via summarized case reports from primarily the 1930s and 1940s, in most cases describing women in psychiatric institutions. In a 2014 deposition in a restraint death case, Dr. Di Maio noted that he and his wife had coined the term “excited delirium syndrome.”[105]

Prone Restraint Studies

At the same time that the Di Maios were promoting the concept of “excited delirium syndrome,” others were conducting research on the safety of prone restraint tactics. Among the studies most widely used to exonerate law enforcement officials in cases of deaths in custody are those conducted by emergency physicians Theodore Chan and Gary Vilke. Drs. Chan and Vilke are part of what the New York Times in a December 26, 2021 investigative report described as a “small but influential cadre of scientists, lawyers, physicians and other police experts whose research and testimony is almost always used to absolve officers of blame for deaths.”[106] Forming a “cottage industry of exoneration,” many of the dozen or so individuals in this group, including Chan and Vilke, have ties with TASER/Axon and/or work as defense experts in death-in-custody litigation.[107]

In 1997, Chan and Vilke sought to determine whether the “hobble” or “hog-tie” restraint position results in clinically relevant respiratory dysfunction. Fifteen healthy volunteers – a small sample size with a questionable ability to generate valid or reliable results – were hogtied. Measurements of lung function decreased by up to 23 percent, which were statistically significant, but the authors deemed them not clinically significant.[108]

In the early 2000s, Chan and Vilke conducted a study in which they placed 25 pounds and 50 pounds on the backs of 10 participants – again a very small sample size – while they were in a prone position.[109] They obtained Institutional Review Board (“IRB”) approval from the University of California’s Human Research Protection Program for this study.[110]

In 2001, Vilke served as a plaintiff’s expert in a restraint asphyxia case when a man with schizophrenia in psychiatric crisis was restrained in a prone position while officers put their weight on his back. At that time, in his deposition, Vilke opined that the weighted restraint killed the decedent. In referring to his studies involving the placement of 25 and 50 pounds on people’s backs, he stated that these were preliminary studies only and seemed to suggest that experimenting with greater weights would be unethical due to the possible danger. He noted, “We don’t want to put 200 pounds on people and kill them.”[111]

After appearing in that case, Vilke took on work as a defense expert in several wrongful death cases against TASER/Axon and law enforcement. Vilke acknowledged in a 2018 deposition that he had worked as a defense expert on behalf of TASER International in “certainly a number of cases” and said he believed that whenever he had testified in cases involving the use of a Taser, he had always testified on behalf of the defense. [112] Further evincing his defense sympathies, Vilke even told a journalist in 2021 that it was “doubtful” that Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin had killed George Floyd by pressing his knee on his neck.[113] The New York Times reported that in a deposition in summer 2021, “Dr. Vilke said it had been 20 years since he had last testified that an officer was likely to have contributed to a death.”[114]

Likewise, in a 2014 deposition, Chan acknowledged that he had been retained by the defense in cases involving the use of a Taser “probably four or five times.”[115]

In 2007, Vilke and colleagues published an article titled “Ventilatory and Metabolic Demands During Aggressive Physical Restraint in Healthy Adults,” in which they put up to 225 pounds (102.3 kg) on the backs of 30 healthy adults who were restrained in a “hogtie restraint” prone position, with 27 participants told to “struggle vigorously” for 60 seconds.[116] The authors found no clinically significant impairments in breathing (ventilatory function) among participants who were either prone or struggling. The authors reported that they received IRB approval from San Diego State and the University of California San Diego (UCSD) Human Research Protection Program for the study. However, repeated efforts by Julia Sherwin to subpoena IRB materials related to this study produced no evidence of a completed IRB review or approval. This raises concerns about whether this study that has since been used as evidence for the safety of prone restraint law enforcement tactics ever passed the ethical and safety hurdles needed to obtain IRB approval.[117]

In two recent restraint death cases handled by Julia Sherwin, the defendant police officers hired Vilke to testify on their behalf.[118] In both cases, Vilke testified that the officers beating and restraining the decedents in a prone position, putting weight on the victims’ backs, and even choking one decedent did not cause or contribute to their deaths.[119]

Role of TASER

TASER/Axon is a U.S. company that develops technology products and weapons for the military, law enforcement, and civilians, including “Taser,” a line of so-called “less-lethal” electroshock “stun” weapons. In 2007, TASER purchased 1,000 to 1,500 copies[120] of Di Maio’s book on “excited delirium syndrome” and distributed free copies. [121] They also gave out other materials on “excited delirium” at conferences of medical examiners and police chiefs.[122] Since there are only about 500 full-time forensic pathologists in the United States,[123] TASER purchased enough copies of Di Maio’s book in 2007 alone to easily cover the entire forensic pathology community, ensuring widespread familiarity with his theory on “excited delirium syndrome.”[124]

Di Maio has acknowledged testifying as a paid expert for TASER/Axon multiple times and stated in 2014 that in the cases in which he was deposed, he always gave the opinion that the Taser did not cause or contribute to the person’s death.[125]

Since there are only about 500 full-time forensic pathologists in the United States, TASER purchased enough copies of Di Maio’s book in 2007 alone to easily cover the entire forensic pathology community, ensuring widespread familiarity with his theory on “excited delirium syndrome.”

American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) White Paper

In 2005, TASER’s national litigation counsel,[126] Michael Brave, co-founded a corporation entitled the Institute for the Prevention of In-Custody Deaths (IPICD) with another TASER defense expert and consultant,[127] John Peters.[128] In October 2008, IPICD held its “3rd Annual Sudden Death, Excited Delirium & In-Custody Death Conference.” IPICD advertised the conference as “the first consensus conference that focuses upon excited delirium,” and promised that “attendees will help make law enforcement, medical, and legal history … focused on arriving at a ‘consensus’ about excited delirium.” IPICD stated that the “findings from this seminal event will then be published in leading medical, legal, and law enforcement journals.”[129]

The conference speakers included TASER and/or restraint death defense experts and consultants such as Chan, Di Maio, Vilke, and Wetli, as well as Dr. Steven Karch[130] and Dr. Deborah Mash.[131] The results of the 2008 IPICD conference were published as the “White Paper Report on Excited Delirium Syndrome” by the American College of Emergency Physicians on September 10, 2009.[132] The co-authors of the white paper included Chan, Mash, and Vilke, as well as TASER’s medical director, Dr. Jeffrey Ho.[133] Despite the close links between the paper’s co-authors and TASER, PHR has been unable to find conflict-of-interest statements or disclosures in connection with the conference or the resulting white paper.

The White Paper Report acknowledges that the pathophysiology of “excited delirium syndrome” is not understood, that there are no tests or standard diagnostic criteria, and that the medical treatment for the “syndrome” is unknown. Regarding the term “excited delirium,” the authors assert that the “issue of semantics does not indicate that excited delirium does not exist” and provide similar ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision) codes such as manic excitement, delirium of mixed origin, agitation, delirium, and abnormal excitement which “describe the same entity as excited delirium syndrome.” They fail to consider that if manic excitement, delirium of mixed origin, agitation, and abnormal excitement (among other ICD-9 codes listed) are the same entity as “excited delirium,” then “excited delirium” cannot be a unique entity. Their Report also does not consider that the forms of delirium or manic excitement in the ICD-9 are not considered lethal. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the main diagnostic tool used by clinicians for psychiatric diagnosis, in fact, recognizes “delirium” as a clinical entity, with “hyperactive,” “hypoactive,” and “mixed” delirium subtypes, but these do not align with “excited delirium.” The Task Force elaborates: “In most cases, the underlying disease will be untreated at the time of [excited delirium] presentation,” which suggests that “excited delirium” is a presentation or manifestation of another cause.[134]

The White Paper Report offers 10 specific features suggesting the presence of “excited delirium” (pain tolerance, agitation, not responding to police presence, superhuman strength, rapid breathing, not tiring despite heavy physical exertion, naked/inappropriately clothed, sweating profusely, hot to the touch, and attraction to/destruction of glass/reflective surfaces). However, it provides no direct citations to the medical literature as to the origins or accuracy of these 10 features in predicting or diagnosing “excited delirium,” nor does it comment on the validity of these features as a screening tool. The descriptions of certain symptoms and signs also play into racist tropes that people of color possess “superhuman strength” and are “impervious to pain.”[135] This is doubly concerning given that Wetli had asserted without evidence 18 years prior that 70 percent of people who died of cocaine-induced delirium were Black men and that “it may be genetic.”[136]

In 2011, the same group of authors published a reiteration of the White Paper Report in the academic, peer-reviewed literature, titled, “Excited delirium syndrome: defining based on a review of the literature.”[137] Based on a review of 18 articles, 10 written by the paper’s authors, the authors again identified 10 features of “excited delirium.”[138]At no point did the authors discuss the lack of and consequent need to develop and test screening tools for “excited delirium” that are valid (able to accurately identify diseased and non-diseased individuals) or reliable (repeat measurements yield the same result). They also provided no statements of conflicts of interest or disclosures.

A 2008 National Institute of Justice (NIJ) report defined “excited delirium” as a “State of extreme mental and physiological excitement, characterized by extreme agitation, hyperthermia, euphoria, hostility, exceptional strength and endurance without fatigue.” Of note, the report was written by the then director of the NIJ but included the disclaimer that “Findings and conclusions of the research reported here are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position and policies of their respective organizations or the U. S. Department of Justice.”[139]

The Death of Martin Harrison

Photo: Courtesy of the Harrison family.

On August 13, 2010, Martin Harrison was arrested for jaywalking in Oakland, California.[140] A warrant check revealed an outstanding warrant for failing to appear in court on a “driving-under-the-influence” charge, and the police arrested Harrison and took him to the Alameda County Santa Rita Jail.[141] During the intake medical screening process, which occurred at approximately 3:00 p.m., Harrison was visibly intoxicated and smelled of alcohol.[142] He told the licensed vocational nurse (LVN) who conducted the intake medical assessment that he drank every day, that his last drink was that day, and that he had a history of experiencing alcohol withdrawal.[143] The LVN determined Harrison needed no medical care and sent Harrison to the jail’s general population without instituting any alcohol withdrawal treatment protocols.[144]

Three days later, Harrison experienced severe alcohol withdrawal, or delirium tremens, hallucinating that he was in his apartment and holding his mattress over his head because he perceived people were trying to shoot him. Ten deputies arrived at Harrison’s jail cell, Tased him, severely beat him, put a spit hood on him, and forced him into a prone position with officers on top of him, until he died.

Alcohol withdrawal and delirium tremens are considered treatable by medical professionals, yet no medical management was offered at any point during Harrison’s stay in jail, including in response to deterioration of his medical condition.

The defendants hired both Di Maio and Wetli as their expert witnesses.

In 2014, Di Maio and Wetli gave sworn deposition testimony in the Harrison case. There was no dispute between the parties that Harrison was experiencing delirium tremens – which, unlike “excited delirium,” has an International Classification of Diseases code – at the time he was severely beaten, Tased, and restrained. Yet Wetli testified in his deposition that Harrison died of “excited delirium” and “is a classic example of death due to excited delirium or the resuscitation that has taken place.”[145] Di Maio testified that Harrison’s “presentation is of somebody in excited delirium” and “you could argue” that Harrison’s death was “a pure excited delirium case.”[146]

Despite their assertions regarding “excited delirium,” Di Maio and Wetli’s depositions confirmed these facts:

- “Excited delirium” has no International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9 or ICD-10) code, which means it cannot be assigned as a diagnosis or as a cause of death for statistical purposes; [147]

- “Excited delirium” has never appeared in any version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the main diagnostic tool for mental health problems used by physicians and mental health workers in the United States, which is now in its fifth edition; [148]

- “Excited delirium” is not recognized by the American Medical Association, American Psychiatric Association, or American Psychological Association.[149]

The Harrison case settled in 2015 after the first week of an eight-week trial, for $8.3 million, along with changes to policies and training in the fifth largest jail in the United States.[150]

“Excited delirium” has no International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9 or ICD-10) code, which means it cannot be assigned as a diagnosis or as a cause of death for statistical purposes.

Medical Literature Review

The PHR team explored two main areas of controversy in the peer-reviewed medical literature on “excited delirium”: 1) the underlying pathophysiology of “excited delirium;” and 2) “excited delirium” as a cause of death.

Consensus in the Literature that the Pathophysiology of “Excited Delirium” Is Unknown

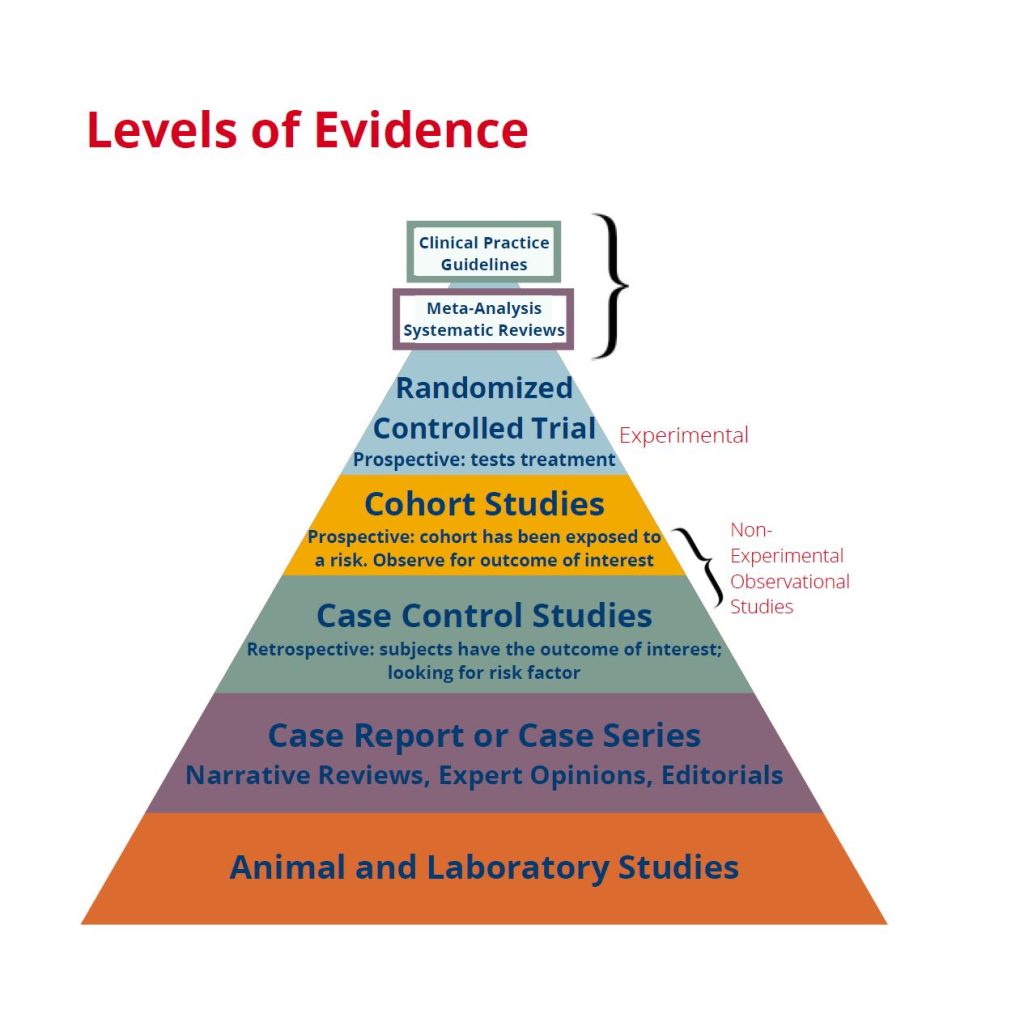

There is consensus across reviewed articles that the pathophysiology of “excited delirium” is unknown, and that there are no telltale or characteristic autopsy findings.[151] Many possible causes of the symptoms associated with “excited delirium” are hypothesized. These include a fight-or-flight response (catecholamine surge) resulting in cardiac arrhythmia, disturbances of dopamine and/or dopaminergic pathways, and restraint-related asphyxia or other use of force.[152] Several systematic reviews of the literature on “excited delirium” conclude that the levels of evidence for any postulated etiology are low to very low, and that the overall quality of the studies is poor.[153] For example, a 2018 systematic review found that 65 percent (n = 43) of the articles were retrospective case reports, case series, or case-control studies, all weaker forms of medical evidence.[154]

Hypothesized Roles of Cocaine Intoxication and Neurotransmitters in Symptoms and Signs of “Excited Delirium”

The consensus among the articles included in the review was that Wetli and Fishbain in 1985 introduced into the literature and medical community the concept of “excited delirium” in the context of cocaine use. The authors reported that “excited delirium” was secondary to cocaine intoxication. Therefore, “excited delirium” is a presentation with an underlying cause.[155] Wetli et al. cite the Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, chapter 20, written by Dr. Zbigniew J. Lipowski, when defining delirium: “There are two major types of delirium: stuporous … and excited….” Lipowski does not use the term “excited delirium.” In fact, cocaine is only referenced in the context of “substance-induced organic mental disorders.”[156] It seems that Wetli et al. initially used “excited” as an adjective to portray the hyperactive form of delirium in their case report.

Later, in 1996, Wetli et al. again discussed cocaine-associated delirium and concluded that, “When cocaine users with agitated delirium die, cocaine should be considered the cause of death, unless there is clear physical evidence that death is due to some mechanism other than cocaine toxicity, such as positional or mechanical asphyxia.”[157]

The reviewed literature accepts that cocaine interacts with different receptors in the body, including the dopamine system in the brain, by increasing dopamine levels through various mechanisms.[158] Increased release or transport of dopamine is hypothesized in some articles to lead to “excited delirium.”[159] However, controversy remains about whether there is any evidence from autopsies that the dopamine system in the brain is associated with “excited delirium.”[160]

Other articles have hypothesized that “excited delirium” may be part of a spectrum of other known medical conditions with other neurotransmitters and pathways involved.[161] No reviewed studies provide conclusive evidence for one hypothesized mechanism over another. Similarly, while death from “excited delirium” in reviewed case series were often attributed to acute myocardial dysfunction leading to cardiopulmonary arrest, exact mechanisms leading to this cause of death are not elucidated.

Debate in the Literature on Whether Prone Restraint Positions rather than “Excited Delirium” Are a Cause of Death in Police Custody

Bell and Wetli et al. defined positional asphyxia as the decedent being found in a position that does not allow adequate breathing and having been unable to free themselves.[162]

In 2020, Strommer et al. conducted an extensive review of the literature and converted all relevant “excited delirium” or “agitated delirium” case reports and characteristics in the literature into a numerical dataset for quantitative analysis.[163] They found that some form of restraint was described in 90 percent of all deaths in “excited delirium.” Restraint increased the odds of an “excited delirium” diagnosis by between 7 and 29 times.[164]

A central debate has thus been whether restraint positions such as prone restraint can physiologically cause positional asphyxia and death. Some case reports have shown that prone restraint was used during sudden and unexpected in-custody deaths.[165] Studies have attempted reenactment of prone and prone restraint positions, including with compression, with no clear pattern of results.

One of the earliest studies evaluated blood oxygenation and heart rate after recovery from exercise while in a restrained and hogtied position.[166] The study found that it took participants longer to recover in the hogtied position and questioned if this could be worsened during a violent struggle. Later, a different study monitored similar parameters for different types of restraint positions over a longer period of time after exercise, but in obese adults.[167] This study concluded that there were no clinically significant effects. However, its data showed that carbon dioxide elimination was reduced in all restrained positions. None of the studies captured scenarios reflective of police encounters, i.e., involving people who may be struggling and agitated, as opposed to lying at rest, as were the participants in these studies.

Some studies have shown statistically significant decreases in lung function measures during prone restraint positioning, though whether these results were clinically meaningful is not clear.[168] Researchers have found large decreases in lung function and/or other physiologic parameters, such as heart rate and blood pressure, and concluded that some prone restraint positioning should be considered a risk factor for sudden death.[169] Other studies have shown that after applying weight to the torso of prone people, there were reductions in cardiac output, blood flow, and/or the diameter of the inferior vena cava (the large vessel which returns blood to the heart that is then pumped to the lungs to be oxygenated).[170] One study measured the effects of prone positioning and restraint for 10 minutes on adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; almost half were unable to complete the study due to uncontrolled respiratory symptoms.[171]

A 2020 study found that some form of restraint was described in 90 percent of all deaths in “excited” or agitated delirium. Restraint increased the odds of an “excited delirium” diagnosis by between 7 and 29 times.

A 2021 study noted that four prominent factors – physical exertion, prone positioning, restraint, and body compression – had been tested in other studies.[172] The researchers used electrical impedance tomography (EIT) to measure the combined impacts of these parameters on ventilation in 17 healthy human participants. They found that under the combined effects of all these conditions, participants had significant and prolonged declines in lung reserve volumes over time, indicating increased work of breathing compared to the control posture of arms at the side.[173]

The researchers noted that these declines took place with an applied weight of 35 percent participant bodyweight, which the study described as “likely less” than the weight an officer would typically apply in an arrest-related encounter. They hypothesized that in true conditions of weighted restraint, the increasing effort needed to breathe while in a restraint posture would become more relevant to the survival of the participant the longer the weight is applied.[174]

The above studies demonstrated measurable hemodynamic and/or respiratory changes detectable in volunteers who were placed in a prone or prone restraint position in a controlled and mild setting. All of these studies had tiny sample sizes composed of primarily healthy volunteers in well-controlled environments. None of the study participants were intoxicated, fearful, or agitated, within or outside the context of mental illness, and none were being forcibly restrained. Therefore, none of the studies replicated an accurate police encounter with someone supposedly in “excited delirium” who may be struggling and agitated due to restraints, as opposed to laying in rest.

It is not known whether the use of prone restraint in conditions such as the forcible restraint of an agitated person could cause significantly worse hemodynamic or respiratory harms than what was found in these studies.

Regarding all forms of neck restraint, however, a 2009 study found that “A force of only 6kg is needed to compress the carotid arteries, which is about the average weight of a household cat or one-fourteenth the average weight of an adult male.”[175] For this reason, among others, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) has held that neck restraints should be classified, “at a minimum, as a form of deadly force.”[176]

Whether Delirium Alone Can Be a Cause of Death

The DSM-5 recognizes delirium as characterized by “disturbance of consciousness” (i.e., reduced clarity of awareness of the environment), with reduced ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention. The three delirium subtypes are hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed. Yet, some literature discussed that delirium alone cannot be a cause of death because, by definition, delirium requires an identifiable underlying organic cause that can be ascertained from the clinical presentation, diagnostic studies, or, in the case of death, by autopsy.[177]

In their 2020 quantitative analysis on “excited delirium,” Strommer et al. discussed the overlap between restraint asphyxia and “excited delirium,” in that the characteristics used to describe “excited delirium” are likely to trigger the use of force and restraint, and that risk factors for “excited delirium” overlap with the risk factors for restraint-related asphyxia.[178]This recent review further reinforces that “excited delirium” does not cause death in unrestrained people.

Delirium alone cannot be a cause of death because, by definition, delirium requires an identifiable underlying organic cause that can be ascertained from the clinical presentation, diagnostic studies, or, in the case of death, by autopsy.

Key Concerns Raised by Review of the Scientific Literature on “Excited Delirium”

The foundations for the diagnosis of “excited delirium” have been misrepresented, misquoted, and distorted. The authors credited with the creation of the term initially used “excited delirium” as a descriptive term for delirium and noted underlying causes. Our examination of the peer-reviewed medical literature on “excited delirium” found that those articles supporting this diagnosis were authored by a small group of people, many of them with ties to TASER/Axon and/or other conflicts of interest. Most of the studies cross-reference each other and highlight non-peer-reviewed sources, such as the Di Maio and Di Maio book Excited Delirium Syndrome, which is not a scientific or medical textbook, is not peer reviewed, and draws unsubstantiated conclusions.[179] For example, Di Maio and Di Maio discuss the 1997 study by Chan et al. multiple times. They describe this study as a “death blow” to the positional asphyxia theory and that believing positional asphyxia is possible “involves suspension of common sense and logical thinking.” Elsewhere, they state that Chan et al.’s study “disproved” the restraint asphyxia hypothesis. Di Maio and Di Maio are not reporting evidence-based conclusions. Chan’s single study with a small, non-representative sample size that does not replicate real-life conditions cannot deliver a “death blow.”

Most of the reviewed literature suggests a relationship between “excited delirium,” death, and restraint. However, these studies have small sample sizes alongside other limitations. The extensive review conducted by Strommer et al. included studies up to April 2020 and summarized all “excited delirium” characteristics. It found that restraint was described in 90 percent of all deaths in the “excited” or agitated delirium medical literature.[180] Notably, they report that asphyxia often lacks pathognomonic signs (clear signs that a particular disease is present) on autopsy.

Our review does not allow for conclusive determinations about whether or not restraint or positional asphyxia is the most likely true cause of death for people said to have died from “excited delirium” while agitated and forcibly restrained. All the studies discussed here, however, including those by authors who claim their studies refute restraint asphyxia and those that did not show clinically significant changes in cardiac or respiratory parameters, indeed did demonstrate measurable changes in cardiac and respiratory parameters. It is unknown if they would be clinically significant in a specific real-world situation, but it is notable that there were cardiopulmonary changes even among participants in calm and controlled settings. It is, therefore, reasonable to hypothesize that these cardiopulmonary changes could worsen and become clinically significant in real-world settings. We found no rigorous scientific research that examines the prevalence of death for people with “excited delirium” who are not physically restrained.

We found no rigorous scientific research that examines the prevalence of death for people with “excited delirium” who are not physically restrained.

Of note, in a December 26, 2021 investigation in the New York Times, the authors analyzed more than 230 scientific papers on restraints, body position, and “excited delirium” in the National Library of Medicine database published since the 1980s. They found that nearly three-quarters of the studies that included at least one author who was in the network of TASER/defense experts “regularly supported the idea that restraint techniques were safe or that the deaths of people who had been restrained were caused by health problems.” Meanwhile, “only about a quarter of the studies that did not involve anyone from the network backed that conclusion. More commonly, the other studies said some restraint techniques increased the risk of death, if only by a small amount.”[181]

Continued Use of “Excited Delirium” to Explain Deaths in Custody and as a Legal Defense to Exonerate Law Enforcement Officials