Executive Summary

In August 2017, Myanmar security forces and Rakhine Buddhist civilians attacked hundreds of villages in northern Rakhine state, massacring thousands of Rohingya Muslim residents and burning their homes to the ground.[1] As of January 2019, that targeted violence and ongoing abuses had prompted approximately 740,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh, where they remain.[2] Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) has collected extensive medical evidence of the human rights violations committed against the Rohingya in those attacks. A PHR report published in July 2018 presented clear medical evidence to corroborate survivors’ accounts of how shootings, beatings, stabbings, and other forms of violence inflicted upon the Rohingya in the village of Chut Pyin made it an emblematic example of the targeted, systematic violence that unfolded in hundreds of other villages across northern Rakhine state.[3]

This supplemental report focuses on a separate, underreported outcome of the August 2017 attacks on the Rohingya: survivors who suffered physical impairments from their wounds that will potentially become long-term disabilities.[4] These disabilities will hinder these survivors’ ease and freedom of movement, limit their ability to seek gainful employment, and otherwise obstruct their ability to live productive, pain-free lives. The plight of these disabled Rohingya survivors highlights how the ruthless violence that the Myanmar security forces and others inflicted on the Rohingya in August 2017 will have a decades-long, painful, life-altering legacy for potentially thousands of survivors and their families.

PHR approached 120 survivors living in refugee camps in Bangladesh to request interviews and interviewed a total of 114 survivors who gave their consent to be interviewed. 90 survivors out of that pool of 114 reported physical injuries resulting from the violence and consented to and subsequently underwent clinical evaluations by PHR medical partners. In total, 43 of these injured survivors were left with long-term disabilities as a result of violence they experienced in or around August 2017.

The vast majority of Rohingya who were disabled as a result of that targeted violence were gunned down as they fled attackers. Many of the bullet wounds have resulted in permanent neurological impairment that limits limb function and causes severe and persistent pain: both can make simple tasks like walking, grasping a pot, or lifting a bag of rice extremely painful or impossible. Other survivors suffered shrapnel wounds from grenades or were injured by landmines laid in fields surrounding Rohingya villages in an apparently deliberate strategy to inflict maximum harm on Rohingya fleeing attack. Some Rohingya survivors who were unable to flee were reportedly seized by Myanmar security forces and brutally beaten, kicked, stabbed, raped, and killed.

The Rohingya profiled in this report are the survivors: unlike the estimated 10,000 killed in the attacks,[5] these people escaped death by being rescued by relatives or by taking refuge in surrounding forests or nearby villages before making the long overland journey to Bangladesh. In many cases documented by PHR, survivors said they had heard that it was unsafe to seek medical treatment inside Myanmar because doctors would allegedly report injured Rohingya to Myanmar authorities. This fear, combined with a longstanding de facto policy of denying health care services to Rohingya meant that survivors often resorted to traditional natural remedies for wound treatment and pain relief during the days- or weeks-long trek to refuge in Bangladesh. PHR clinicians have concluded that this lack of adequate medical attention often exacerbated already severe wounds: these injuries were often worsened by delayed surgery, while infections led to amputations that earlier treatment might have prevented.

The vast majority of Rohingya who were disabled … were gunned down as they fled attackers. Many of the bullet wounds have resulted in permanent neurological impairment that limits limb function and causes severe and persistent pain: both can make simple tasks like walking, grasping a pot, or lifting a bag of rice extremely painful or impossible.

PHR asserts that the attacks by Myanmar security forces should be investigated as crimes against humanity and supports recommendations by a United Nations (UN) fact-finding mission to refer Myanmar to the International Criminal Court or an ad hoc criminal tribunal for accountability for those abuses. PHR is convinced that, by inflicting indiscriminate injury and thus long-term disability on many Rohingya, Myanmar security forces also violated the right to health and the right to work of their Rohingya victims. Myanmar now has forward-looking redress obligations toward Rohingya who were disabled by the 2017 attacks, including guarantees of financial compensation for those who can no longer work; free and comprehensive access to medical services and education; and long-term rehabilitation services for disabled Rohingya if and when the Myanmar government and the international community can guarantee their safe and voluntary return to Myanmar.[6][7]

Muriam’s Story

Five-year-old Muriam Khathu (Profile 5) was at home with her parents and grandparents when soldiers began approaching their village, firing rifles and throwing and firing grenades at some of the Rohingya houses. The family ran out of the house. Soldiers shot and killed Muriam’s father, while several members of Myanmar’s security forces grabbed the 40-pound Muriam and threw her against a wall. They began stomping on her and kicking her with their combat boots, ignoring the pleas of Muriam’s mother and grandparents that they stop.

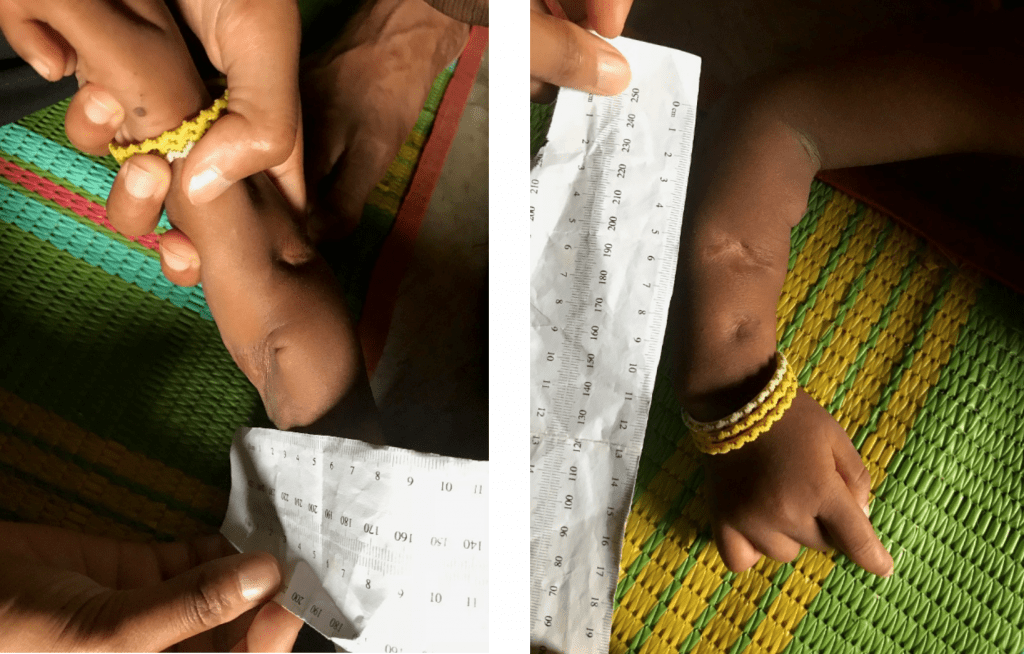

When Muriam’s assailants moved on, Muriam’s family took shelter in the forest near their village before setting out on the long journey to Bangladesh. They carried Muriam on a makeshift stretcher, but she still cried out in pain every time she was moved. Once in Bangladesh, Muriam was sent to a hospital, but the damage could not be undone: she had suffered a pelvic fracture and serious neurological injury as a result of the attack. She could move her legs only slightly and was unable to walk or bear any weight on them. Months after the attack, she said she still felt pain whenever she moved. According to a clinical examination carried out by PHR medical partners on the ground, the presence of ongoing pain and Muriam’s inability to walk more than two months after the injury indicated a low likelihood that Muriam would ever be able to walk or move without pain.

Members of Myanmar’s security forces grabbed the 40-pound Muriam and threw her against a wall. They began stomping on her and kicking her with their combat boots, ignoring the pleas of Muriam’s mother and grandparents that they stop.… [Today,] Muriam is unable to walk, play, or even sit up.

If Muriam and her family return to northern Rakhine state, many difficulties await. The rural region faces severe food insecurity and its residents are highly dependent on subsistence farming. Muriam will most likely be limited in her ability to work or do the physically demanding chores intrinsic to life in rural Rakhine State. Muriam is unable to play, walk, or even sit up. Her mother is responsible for basic personal hygiene tasks such as helping her use the toilet. Muriam will most likely have extremely limited medical support if she returns to Myanmar: the Rohingya have faced state-sponsored discrimination in accessing health services for years.[8] Even if Myanmar were to end such discriminatory practices, there are fewer than 1,400 hospital beds in Rakhine state to service a population of more than three million people,[9] imposing extremely limited access to services. The lack of adequate support services for people with disabilities in Rakhine state will likely place severe burdens on their caregiver family members. Longtime caregivers of people with disabilities are at high risk of poor health outcomes themselves, including depression and shortened life-expectancy due to the stresses imposed by caregiving.[10]

For those like Muriam whose interviews are documented in this report, the violence directed at them over a period of days in 2017 has resulted in the high likelihood of a lifetime of chronic pain and disability.

Photo: Salahuddin Ahmed for Physicians for Human Rights

Introduction

For centuries, Muslim Rohingya people have lived in Rakhine state on the western coast of Myanmar, a predominantly Buddhist country. Since the Myanmar military junta stripped the Rohingya of citizenship in 1982, the Rohingya have been stateless and subjected to decades of human rights violations, including denial of the right to health and education, limited political participation, restrictions on freedom of movement, forced displacement, arbitrary detentions and killings, forced labor, and trafficking, among other abuses.[11]

Following attacks on Myanmar security forces by the insurgent Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army in October 2016 and again in August 2017, the Myanmar military unleashed a wave of violence on Rohingya communities.[12] PHR’s July 2018 report, “The Chut Pyin Massacre: Forensic Evidence of Violence Against the Rohingya in Myanmar,”[13] detailed the brutal attacks that took place in one village. As the violence was widespread and systematic throughout Rakhine state, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) conducted a sub-analysis: in a survey of some 604 Rohingya hamlet leaders, 534 (88 percent) reported violence against their hamlets, with more than half of the 534 reporting beatings and shootings, and almost a third reporting rapes or sexual assault.[14] The Myanmar military’s ruthless attacks on Rohingya civilians from August 2017 onward has driven some 740,000 people into neighboring Bangladesh.[15] Evidence gathered by PHR supports the conclusions of a United Nations fact-finding mission, which found that actions by Myanmar security forces indicated “genocidal intent.”[16][17]

To gather the data used in this report, PHR conducted four visits to Bangladesh after October 2017 to interview and carry out clinical examinations of Rohingya survivors of these attacks. PHR interviewed a total of 114 survivors. Of those, 24 people were witnesses who had sustained no injuries and were therefore not given a forensic exam. In total, 90 survivors who had suffered injuries underwent a PHR clinical evaluation consisting of both an interview and a physical exam. Of these survivors, 43 were left with long-term disabilities – defined as physical impairment, activity limitations, and restrictions in participating in activities of daily life – as a result of the attacks.[18] These survivors were from 19 different villages throughout northern Rakhine state.

In September 2018, the UN Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) published a 444-page report about human rights abuses against the Rohingya.[19] The mission’s report concluded that there was evidence warranting criminal prosecution for crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide.[20] The report names top military officials as targets for investigation and prosecution and also blames civilian authorities for “spreading false narratives, denying the wrongdoing of the (security forces), blocking independent investigations … and overseeing the destruction of evidence.”[21] The Myanmar government rejected the report’s findings as “false allegations.”[22]

The FFM’s findings were echoed in the results of the first-ever quantitative survey, carried out by PHR, of Rohingya leaders displaced to refugee camps in Bangladesh. The analysis of the survey’s results was published in a March 2019 peer-reviewed Lancet Planetary Health article, which concluded that “in 2017, the Rohingya ethnic minority population of Northern Rakhine State were the targets of a campaign of widespread and systematic violence, including violence by state forces.”[23]

To date, Myanmar authorities have failed to conduct impartial and independent investigations into these events and have not fully cooperated with the UN and other bodies seeking to do so. A four-member commission formed by the Myanmar government to investigate the alleged crimes announced in December 2018 that it had found no evidence to corroborate the UN’s accusations,[24] an assertion roundly rejected by human rights groups.[25] The UN Security Council is currently negotiating a draft resolution to address the Rohingya refugee crisis which would include the option of imposing sanctions on the Myanmar government, though news reports suggest that Russia and China have boycotted that initiative.[26]

PHR is publishing this report based on testimonies and clinical evaluations of individual cases to contribute to documentation and investigation efforts, so that those who perpetrated these crimes can be held accountable and that survivors may be given redress. While this report focuses on the rights of Rohingya survivors disabled in the violence of August 2017 to redress, and, specifically, to access health care and rehabilitative services, this does not discount the need for all people with disabilities in Myanmar to access those same services, especially those who face discriminatory obstacles in accessing health care. Likewise, this report does not discount the rights to reparations of Rohingya who were not injured in the attacks as well as the many survivors who lost loved ones (or entire families), property, and, thus, their economic viability.

Methodology

Field Investigations

Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) conducted four visits to Rohingya refugee camps (Balukhali, Jamtoli, Kutupalong, and Thangkali) near Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh between October 2017 and July 2018. During an initial visit in October 2017, the PHR clinical team established contact with local health providers working in camps in the area and assessed the need to collect scientific and medical evidence in the form of clinical evaluations. In December 2017, the PHR medical team returned to conduct interviews and clinical examinations of survivors from dozens of villages across Rakhine state, from where most Rohingya have fled since the August 2017 attacks. PHR carried out a second field investigation in Bangladesh in March 2018, and a third in July 2018. PHR then did secondary data extraction to identify evaluations of survivors with disabilities and then conducted an analysis of those particular cases. This report follows the publication of a larger project whose methods and main findings have been previously described in the March 2019 peer-reviewed Lancet Planetary Health article, “Violence and mortality in the Northern Rakhine State of Myanmar, 2017: results of a quantitative survey of surviving community leaders in Bangladesh.”[27]

Interviews and Clinical Examinations

The findings of this report are based on two-part assessments – interviews and clinical examinations – conducted in private locations through a Rohingya language interpreter. The PHR research team collaborated with local organizations, health facilities, and community informants utilizing purposive and snowball sampling to identify survivors with physical injuries from the violence. The PHR research team also interviewed other key informants, including community leaders, medical professionals, activists, lawyers, journalists, and others. All survivors interviewed were adults or accompanied minors who self-identified as Rohingya and who were in surrounding hospitals or lived in refugee camps in the Ukhiya and Teknaf areas south of Cox’s Bazar. PHR excluded anyone who arrived before August 27, 2017 and/or was unable to provide consent.

The PHR team interviewed and evaluated 114 survivors. Twenty-four people were witnesses who had sustained no injuries and who therefore did not undergo a clinical examination. Ninety survivors who had suffered injuries underwent a PHR clinical evaluation consisting of both an interview and a physical exam. Each of these assessments began with a semi-structured interview to collect information on the survivor’s demographics and their personal experiences, as well as when they first noted any disturbances in daily life in late August 2017 and how they arrived in their current location. Questions focused on the survivor’s own experiences and on instances in which they witnessed abuse.

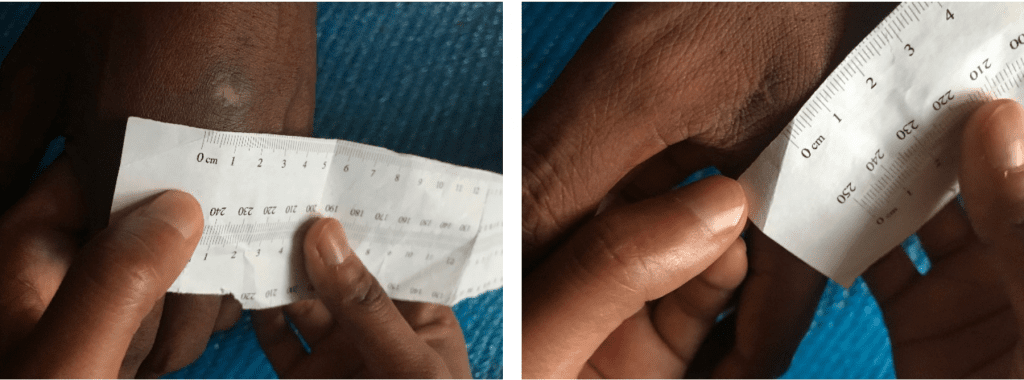

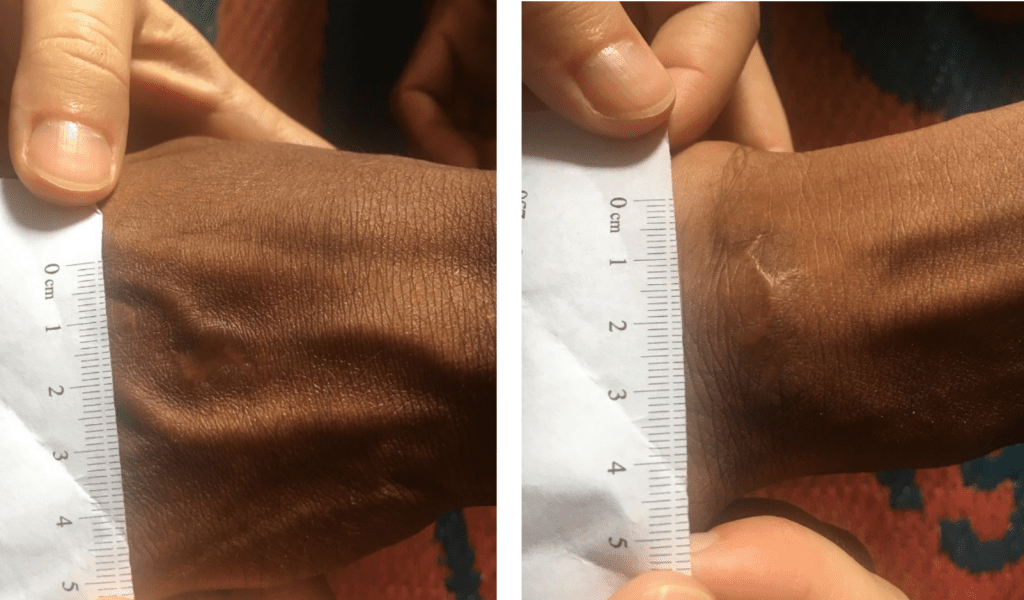

PHR then conducted physical examinations to identify injuries, scars, wounds, and disabilities based on the principles and guidelines of the “Manual on Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment,” commonly known as the Istanbul Protocol. The Protocol is the international standard to assess, investigate, and report alleged instances of torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment.[28] This study focused on physical forensic examinations of the area of reported injuries; available diagnostic images, laboratory tests, and other medical records were also reviewed.

Data Extraction and Analysis

PHR investigators attempted to assess disability according to the severity of the impairment and the likelihood that it would constitute a long-lasting impediment to a survivor’s ability to work, do domestic chores, and otherwise live a fully-functional life.

To identify persons with disabilities, a PHR consultant reviewed the 90 evaluations of survivors with injuries. We defined disability as “a restriction or lack (resulting from an impairment) of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being as defined by the World Health Organization.[29] In this definition, a person qualifies as having a disability if their functional issues fulfill at least one of the following criteria:

- Impairments – The injury causes problems in body function or structure that affect daily life.

- Limitations in Activity – The person has difficulty executing a task or action at least once a day because of the injury.

- Restrictions in Participation – The person is restricted by the injury from involvement in a life situation that would otherwise be available, such as transportation or employment.

Based on WHO criteria, the PHR consultant then classified those people with long-term disabilities. We considered people to have long-term disabilities if they had the disabilities defined above at the time of the assessment and the clinical evaluator mentioned that the disability would likely persist as a long-term disability that would affect the person throughout their lifetime. We excluded psychological and psychosocial disabilities from this analysis. Given that this was a secondary analysis of previously collected data that was not specifically focused on collecting data on long-term disabilities, the consultant reviewed the evaluation documents and any available medical records or diagnostic data; they also consulted relevant clinicians who conducted the clinical evaluations for their assessment of whether survivor injuries and their effects qualified as long-term disabilities, the level of disability, and the impact of the disability on routine activities.

Of the 90 injured Rohingya evaluated by PHR, 43 were left with long-term disabilities as a result of the attacks. These disabled survivors were from 19 different villages throughout northern Rakhine state. The survivors with disabilities included 32 adults (five women and 27 men) and 11 children under the age of 18 (four girls and seven boys).

Consent and Ethics Approval

The PHR researchers obtained consent from each interviewee through an interpreter, following a detailed explanation of PHR’s work, the purpose of the investigation, and its voluntary nature. For reasons of safety and confidentiality, PHR has replaced the names of survivors with pseudonyms and blurred their faces in the images used in this report.

PHR’s Ethics Review Board provided guidance and approved this study based on regulations outlined in Title 45 CFR Part 46, which are used by academic Institutional Review Boards in the United States. All of PHR’s research and investigations involving human subjects are conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 2000, a statement of ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects, including research on identifiable human material and data.[30]

PHR Clinical Team

The clinical team involved in field investigations included in this report was composed of six PHR medical experts: Rohini Haar, MD, MPH; Parveen Parmar, MD, MPH; Rupa Patel, MD, MPH; Satu Salonen, MD; Homer Venters, MD, MS; and Karen Wang, MD, MHS.

Limitations

This report sheds light on how multiple attacks on Rohingya living in northern Rakhine state unfolded and provides key forensic evidence on how these attacks had a long-term physical impact on 43 people from 19 separate villages. However, this report does not provide a full analysis of the human rights violations faced by all people from these villages or by the broader Rohingya population. The survivors were interviewed between three and 11 months after the attacks and demonstrated symptoms of trauma, which may have exacerbated recall bias. In addition, given the range of months post-injury at which an individual was interviewed (e.g., some at three months), it would not be possible to determine a definitive diagnosis of permanent disability in all the survivors. We utilize the term “long-term disability” to encompass these disabilities, while acknowledging that rehabilitation services, time, and healing may improve some physical outcomes for some of these survivors.

Definitions of a disability differ, although the WHO describes disability as an “umbrella term, covering impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions.”[31] While most definitions of disability include psychosocial impairments, limitations in the field made it impossible for PHR to conduct widespread and in-depth examinations to determine whether survivors suffered psychosocial disabilities as a result of the attacks. However, it is likely that many survivors suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and other potentially disabling mental health conditions, a phenomenon that has been documented by other humanitarian organizations working with Rohingya survivors in Bangladesh.[32]

Terminology

In this report, the term “Rakhine Buddhist” refers to Buddhist people of Rakhine ethnicity, and “Rohingya” refers to civilian Muslim people of Rohingya ethnicity. “Myanmar security forces” encompasses the military and Border Guard Police officers; the term “Rakhine Buddhist civilians” in this context refers to Rakhine civilians who were armed or appear to have acted in concert with, or at least with acquiescence from, Myanmar authorities during attacks on the Rohingya.[33]

The Rohingya in Myanmar: A Short History[34]

The Rohingya were considered citizens of Myanmar (then “Burma”) under the Constitution of 1948, when the country declared independence after British rule. In 1962, the military junta took over Myanmar, and Myanmar’s Citizenship Act of 1982 fully stripped the Rohingya of their citizenship rights. Myanmar continues to deny citizenship to the Rohingya and to implement discriminatory laws and policies that have led to widespread human rights violations against the Rohingya.[35]

In 2012 and 2013, attacks on Muslim villages uprooted 140,000 Rohingya and made them internally displaced people within Myanmar.[36] In 2014, Myanmar’s first country census in 30 years did not include the Rohingya as a recognized ethnic group and the government initiated a citizenship verification program,[37] whereby the Rohingya were instructed to register as “Bengali.”[38] Many Rohingya resisted doing so for fear of being categorized as “illegal” foreigners. In 2015, a new law was passed requiring that political leaders be citizens of Myanmar, thereby excluding Rohingya from being candidates and from voting.[39] In 2015, the Myanmar government announced that people would be given National Verification Cards (NVCs), but because the process was not transparent and lacked an option to self-identify as Rohingya, many refused the NVC for fear of being registered as “illegal” and expelled from Myanmar. The government increased pressure on the Rohingya to register for the NVC.[40]

In October 2016, the insurgent Arakan Rohingya Solidarity Army (ARSA) attacked three Border Guard Police outposts, killing nine officers. The following day, the Myanmar government declared ARSA “terrorists” and responded with military force, implementing a counterinsurgency campaign. According to the International Organization for Migration, these operations drove an estimated 87,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh between October 2016 and July 2017.[41]

In August 2017, ARSA – armed primarily with knives and homemade bombs – raided 30 police outposts, killing 12 members of Myanmar’s security forces.[42] This was followed by a brutal security crackdown involving arrests, disappearances, beatings, stabbings, mass shootings, rape and sexual violence, looting, and the burning of Rohingya villages.[43] The military has denied responsibility for attacking Rohingya civilians, stating that its offensive was a counterinsurgency campaign focused on ARSA.[44] A UN fact-finding mission used satellite imagery and firsthand accounts to confirm that some 392 villages (40 percent of all settlements in northern Rakhine state) – or nearly 38,000 individual buildings – had been partially or totally destroyed.[45] A separate report by the Public International Law & Policy Group said that the “scale and severity of the attacks and abuses … suggest that the goal was not just to expel, but also to exterminate the Rohingya.”[46] Some 740,000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh since the start of the violence in August 2017.

Findings: Disabled by Targeted Violence

The attacks on the Rohingya described by those interviewed for this report followed a similar pattern. Usually in the early morning, when families were at home, Myanmar security forces – sometimes accompanied by groups of Buddhist Rakhine civilians who, in some instances, were armed – entered a Rohingya village. Some Rohingya woke up to the sound of gunfire or shouts. Others saw houses being lit on fire or looted. They saw fellow villagers being rounded up, arrested, beaten, or shot at. Realizing their best chance for survival was to flee to the nearby hills, many attempted to dash out of their homes, often carrying babies, elderly relatives, or the disabled.

Many people were gunned down as they ran. Others stepped on landmines that appeared purposely placed to target fleeing civilians or were hit by shrapnel from rocket launchers or grenades. Some were unable to flee and were brutally beaten after having surrendered to their attackers. Although the systematic gang rape, mutilation, and torture of Rohingya women by Myanmar security forces have been extensively documented elsewhere,[47] only one of the survivors that PHR interviewed for this report elected to recount such incidents herself.

Those who survived were eventually rescued by relatives or managed to take refuge in the surrounding forests, farmlands, or villages. In many cases, local health workers denied survivors necessary medical treatment. Many survivors had heard, directly or indirectly, that Myanmar authorities required doctors to report injured Rohingya to the authorities, thus putting the lives of those injured Rohingya at grave risk. As a result, most survivors interviewed for this report used only herbal remedies for their wounds, or were given bandages, disinfectant, and over-the-counter painkillers from local shops or clinics prior to their arrival in Bangladesh.

Many people were gunned down as they ran. Others stepped on landmines that appeared purposely placed to target fleeing civilians or were hit by shrapnel from rocket launchers or grenades. Some were unable to flee and were brutally beaten after having surrendered to their attackers.

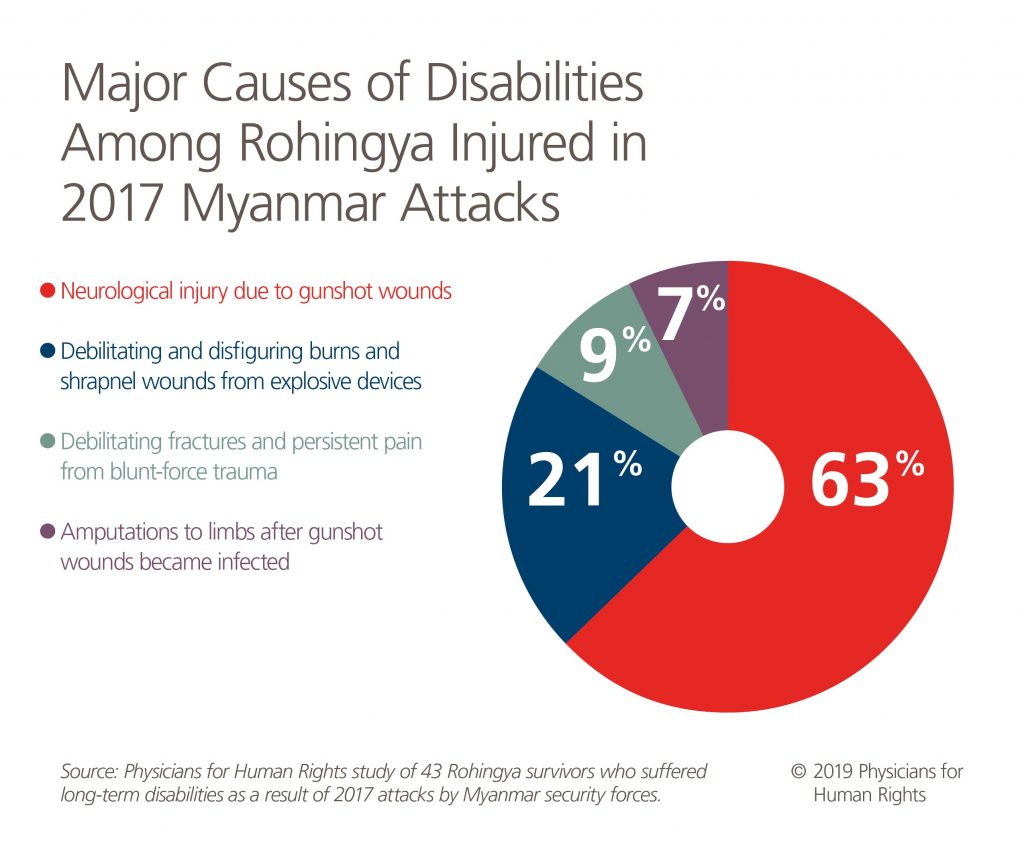

Many survivors now live with physical impairments that will potentially become long-term disabilities. Major causes of disabilities include: neurology injury due to gunshot wounds in 27 out of 43 disabled individuals (63 percent); amputations to limbs after gunshot wounds became infected (three people, or seven percent); debilitating fractures and persistent pain from blunt-force trauma (four people, or nine percent); and debilitating and disfiguring burns and shrapnel wounds from explosive devices (nine people, or 21 percent).

PHR documented significant variance in the type and severity of physical impairments that Rohingya survivors reported. Some survivors could not walk more than a few steps, while others could walk but had pain or a limp and could not remain on their feet for extended periods. Some had lost all use of an arm, while others had lost muscle control in their hands and could not firmly grasp objects. Most of these injuries were likely exacerbated by the lack of immediate medical treatment post-injury, and some examinations indicated a lack of appropriate physical therapy or other rehabilitative services for the affected limb. At the time of writing this report, several organizations in the refugee camps of Bang-ladesh were providing these services, but it was unclear how many Rohingya survivors in need of such services were aware of or had access to them.

Disabilities from Gunshot Wounds

The majority of disabled Rohingya survivors (27/43) examined by PHR medical experts were shot, often while fleeing from the scene of an attack by Myanmar security forces or Buddhist Rakhine civilians. Seven Rohingya examined by PHR medical experts had wounds that were consistent with their testimonies of having been shot from behind while fleeing. Other survivors sustained gunshot wounds when they left an area of relative safety to go back and get an infant or an elderly family member left behind in the epicenter of the attack. Still others were shot while seeking refuge from their attackers – sometimes by Myanmar security forces shooting indiscriminately into areas around Rohingya villages. Those gunshot wounds inflicted permanent neurological damage to the limbs of survivors.

Gunshot wound survivors evaluated by PHR included survivors who had a range of physical disabilities. Three people had lost a majority of function in at least one leg, meaning that they could not walk without crutches or assistance. Six more people had persistent pain and partial loss of nerve functioning, so they could walk only with difficulty and for only a few minutes at a time. Three people had suffered from nerve injury in an arm or a hand – with resulting muscle atrophy, or a wasting away of muscle mass, that results from disuse – while seven others experienced a loss of feeling or sensation in their arms and hands and could no longer do things like hold a pot or a pan or carry their child. Finally, two people had limited motion and chronic pain in their shoulders or neck secondary to gunshot wounds. These disabilities will be a significant impediment in a society in which physical labor is essential to livelihood. “I could work and run normally before. Now I cannot…. People say: ‘He got an injury.’ I feel bad about that – I used to be a normal person,”[48] Uddin said.

Eighteen-year-old Salim Uddin (Profile 18) worked as a farm laborer and lived with his parents, brothers, wife, and son in the village of Chita Para. At about 4 p.m. on a day in late August 2017, Uddin’s family was at home when they saw military personnel shooting at and burning houses. The entire family ran from their home and into the surrounding hills. But Uddin was shot in both legs: “I felt a sharp pain and a hard shake in my body, and I lost consciousness.” Eventually, his father and brothers rescued him and helped carry him to Bangladesh, where he received surgery. He still had difficulty walking and thus working, which made him feel that he no longer belonged. “How can I [farm again]?” he said. “I have to try to do as much as I can, but I can’t hold anything firmly and so I won’t be able to work.”[49]

“I could work and run normally before. Now I cannot…. People say: He got an injury. I feel bad about that – I used to be a normal person.”

Salim Uddin, 18, gunshot injuries to both legs

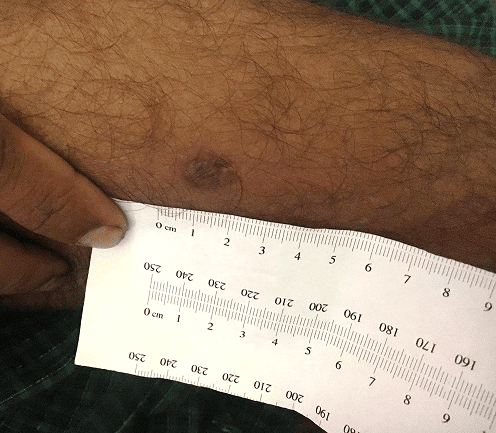

Faizal Islam (Profile 27) was a 28-year-old farmer who lived with his wife and two children in the village of Pa Da Kah Yua Thit. On August 25, 2017, he saw Myanmar security forces entering the area. Villagers were shot at as they ran. Islam ran with the others and was shot in his left hand, but he was able to hold onto the wound and keep running until he reached the forest, where he stayed for six days before setting out for Bangladesh. Despite receiving immediate medical attention in Bangladesh, he has lost basic motor function in his left hand, rendering him unable to grasp and hold onto objects of any size or weight.

Photo: Salahuddin Ahmed for Physicians for Human Rights

For some survivors, intense, chronic pain from gunshot wounds effectively disabled an injured limb. During an attack around August 25, 2017, Myanmar security forces shot 14-year-old Anowar Hussein (Profile 26) in his right shoulder as he ran to a nearby nut garden to hide. He pretended to be dead, and when the military retreated, he fled to the forest and eventually crossed the border into Bangladesh. When PHR medical experts interviewed him almost a year after the attack, Hussein still suffered from intense, chronic pain that caused him to have a limited range of motion in his shoulders and his right arm, which he could not raise more than 90 degrees. He had previously worked jobs that required physical labor, such as herding cattle.

“I feel bad. It is itchy here at my wound. Sometimes I can’t stand it, the itching and the pain. I can move (my arm) a bit at normal times. But when it becomes very painful, I can’t move at all,”[50] Hussein said.

“I feel bad. It is itchy here at my wound. Sometimes I can’t stand it, the itching and the pain. I can move (my arm) a bit at normal times. But when it becomes very painful, I can’t move at all.”

Anowar Hussein

Amputations Because of Gunshot Wounds

Three of the survivors (3/43 or seven percent) sustained gunshot wounds in limbs that then became infected and had to be amputated. This was likely a result of spending days or weeks hiding from Myanmar security forces without access to adequate medical care.

Mohammed Erfan (Profile 1), a 15-year-old, was at home with nine family members in late August 2017 when security forces and civilians began attacking and arresting Rohingya villagers, looting their homes and then burning them down. Erfan suffered a gunshot wound to his upper left arm as he fled toward the forest. He kept running until he lost consciousness. When he regained consciousness, he was alone and saw that his village had been destroyed. He made his way into the forest and eventually met up with an uncle. They spent two months in the forest, too terrified to leave. Eventually they trekked to Bangladesh, where medical personnel immediately referred Erfan to a hospital to have his arm amputated. Since then, his uncle has been reunited with his wife and children, leaving Erfan alone in the camp. Erfan did not know how he would find work or engage in any other productive activity without his left arm, and he appeared to be suffering extreme trauma and abandonment in addition to his physical disability.

Photo: Salahuddin Ahmed for Physicians for Human Rights

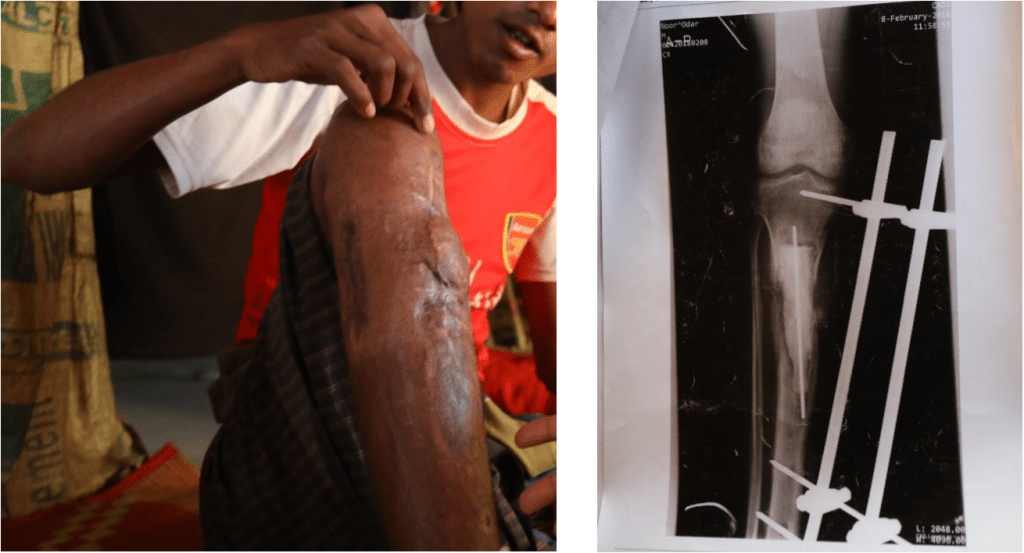

Another patient, 26-year-old Halek Husson (Profile 12) from Mirullah village, had to have an above-the-knee amputation of his left leg after a gunshot wound he suffered became infected. He now walks on crutches and can stand on his right leg for only a few minutes at a time without support. He still felt pain in his left leg after the amputation, mostly at night.

Blunt-Force Trauma

Four survivors (4/43 or nine percent) suffered blunt-force trauma such as beatings or kicking.

This was the only category in which a majority of the victims with disabilities interviewed by PHR (three out of four) were female. As in Muriam’s case, described above, these other two women were unable to escape and were detained by the Myanmar security forces, who subjected them to beatings or other forms of brutality.

Photo: Salahuddin Ahmed for Physicians for Human Rights

Myanmar security forces attacked Bi Bi Zuhra’s (Profile 15) village in the morning of August 30, 2017. Upon seeing soldiers and helicopters, Rohingya civilians fled to the river, but the security forces caught up with them. They rounded up the men and children and killed them with guns and machetes: Zuhra’s husband and five of her six children were killed in front of her. Afterward, she and six other women were taken into a home by force. The men beat her and the other women and broke her wrist. She was then raped by a man who afterwards used a knife to cut her throat in two places and left her for dead. In addition to the severe psychological trauma she endured, Zuhra developed a bony deformity on the end of her forearm that resulted in limited wrist function in that arm.

Burns and Other Injuries from Blast Explosions or Projectile Devices

Nine of the survivors (9/43 or 21 percent) had wounds from explosive devices. Some of them distinctly remembered being shot at by military forces with a rocket launcher or having stepped onto something that exploded under their feet, suggesting that they had stumbled onto landmines that appeared to have been planted as part of an intentional strategy of the Myanmar security forces to kill or injure escaping Rohingya. Others could not specify the type of weapons that had been used to attack them and were only aware that something had exploded close to them.

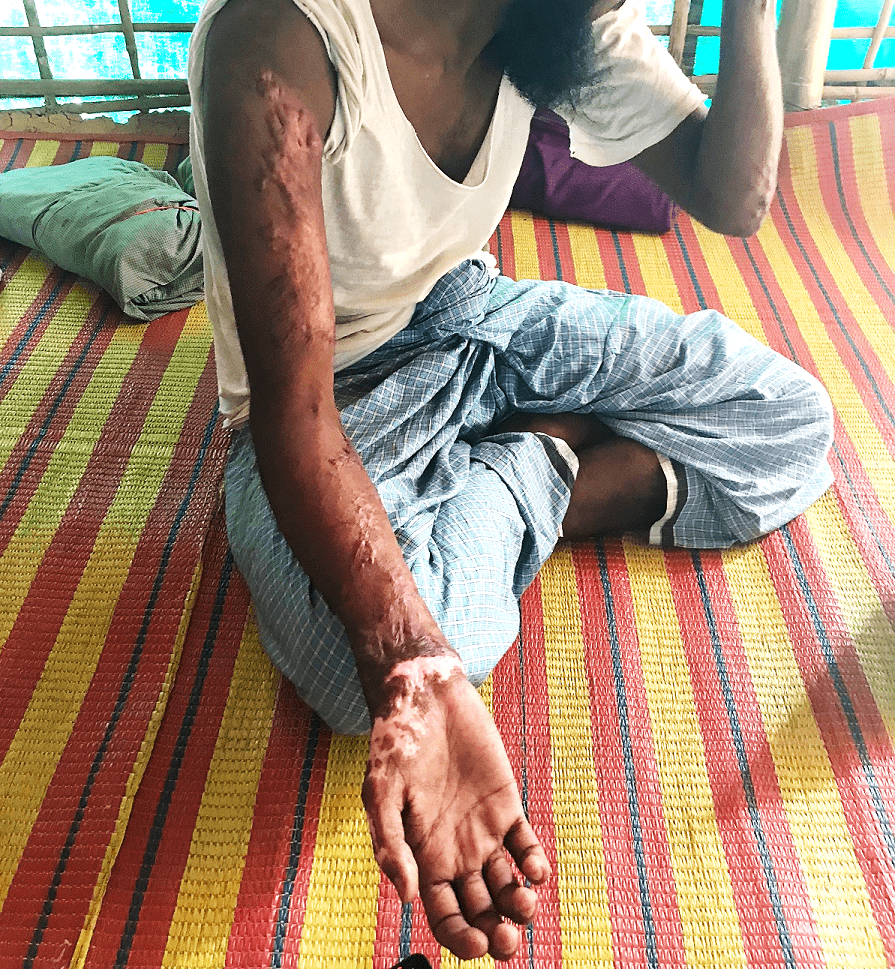

Twenty-five-year-old Monzur Alom (Profile 17) was a teacher at a mosque in the village of Tin May. He was at home asleep with his wife and three children when he heard shooting. He saw military and Border Guard Police, which he recognized by the uniforms they wore, entering the village and shooting guns. He and his family ran out of the house to escape the attack, but Alom turned back when he realized they had left behind his eight-month-old son. He saw Myanmar security forces firing a rocket launcher in the direction of fleeing villagers but made a dash for it with his son held to his chest. Seconds later, something exploded directly in front of him, hitting and instantly killing his son. The explosion inflicted shrapnel wounds and severe burns on Alom. Despite his wounds, he ran until he lost consciousness. Eventually, he was transported to Bangladesh with the help of his family. Extensive scarring to his hands and wrists will make it difficult for him to do any kind of physical labor, as those injuries prevent him from fully flexing or making a fist with his right hand.

Abu Tayub (Profile 25), a 25-year-old farmer from Gu Dar Pyin, was fleeing approaching Myanmar security forces on August 25, 2017 when he was hit by the blast from a landmine. The explosion killed five other fleeing villagers around him and seriously injured his left arm. He hid in the forest for three days before traveling to another village, where somebody helped him bandage his wound. After seven days there, he traveled to Bangladesh, where he was sent to a hospital and received skin grafts. He has lost all function in his left hand, likely rendering him unable to perform many of his previous farming activities. “I used to be a hard laborer,” said Tayub. “I can’t work now, I can’t even lift the small water pot that is used at the latrine…. I feel so sorry that I can’t use my hand anymore.”[51]

“I used to be a hard laborer…. I can’t work now, I can’t even lift the small water pot that is used at the latrine…. I feel so sorry that I can’t use my hand anymore.”

Abu Tayub, 25, landmine injury

Human Rights Analysis

Crimes Against Humanity

The Rome Statute, the treaty which established the International Criminal Court (ICC) and defines core international crimes, enumerates murder, torture, rape and other forms of sexual violence, enforced disappearances, and the forcible transfer of populations as crimes against humanity. The Statute extends the definition of crimes against humanity to “inhumane acts … intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health.”

The August 2017 attacks by Myanmar security forces against the country’s Rohingya minority, which left the 43 survivors whose cases are documented in this report – and quite possibly many more – with long-term disabilities, fit this definition.

These crimes have been thoroughly documented by Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and other credible organizations: 88 percent of the 604 village leaders surveyed by PHR in August 2018 reported violence in their hamlets in or around August 2017, clearly showing that the attacks were widespread and followed notable patterns. Among many other crimes, security forces shot at villagers who were fleeing attack or randomly shot into forests and other places where survivors sought refuge.

PHR’s research demonstrates that the Myanmar military’s actions must be investigated per the Rome Statute or another ad hoc tribunal with jurisdiction to try individuals for serious international crimes, including crimes against humanity and genocide. While Myanmar is not among the 124 nations that are party to the Statute, the Statute allows the United Nations Security Council to refer non-signatories to the court.[52]

Genocide

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (commonly referred to as the “Genocide Convention”),[53] which Myanmar ratified in March 1956,[54] specifically criminalizes acts “committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” The Convention notes that the following acts are punishable: genocide; conspiracy to commit genocide; direct and public incitement to commit genocide; attempt to commit genocide; and complicity in genocide. The crimes committed by Myanmar security forces against the Rohingya and detailed in this report may constitute violations of the Genocide Convention.

Unlawful Use of Landmines

The Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction, known as the Mine Ban Treaty, to which 164 nations are party, forbids the use of antipersonnel landmines, and further extends this prohibition by banning signatory nations from using, stockpiling, developing, or producing these weapons entirely.[55]

Survivor accounts indicate the possible unlawful use of landmines by Myanmar security forces against Rohingya civilians. Some survivors described seeing, hearing, or being the victims of explosive weapons. Some reported seeing or being hit by a rocket or a grenade, while others had blurred memories and only knew that they had been burned or hit with shrapnel from a nearby explosive. The Myanmar government claims that the Arakan Rohingya Solidarity Army is responsible for placing landmines in Rakhine state, yet numerous reports have documented that the Myanmar military actively placed landmines in the area prior to their attacks on Rohingya villages.[56]

Three survivors, all from the village of Gu Dar Pyin, described surviving or witnessing the use of landmines. Abu Tayub said he had been fleeing the Myanmar forces and running toward the mountains, and when he reached a field outside his hamlet landmines began exploding all around him. He said that five people he was running with died instantly, and that his left hand was injured in the blasts. Mustafa Kamal, a 23-year-old who was severely wounded but not permanently disabled by the attacks, also reported stepping on an object that exploded under his feet, leaving him with a shrapnel wound to his left arm. Rashid Ahmed (Profile 33), a gunshot victim from Gu Dar Pyin, was not hit by a mine himself but said he had seen landmines exploding and saw three people die instantly as a result.

While Myanmar is not a party to the Mine Ban Treaty, its use of landmines is unlawful both in times of conflict and non-conflict, as these weapons do not discriminate between civilians and combatants, thereby affecting a breadth of human rights ranging from the right to life to freedom of movement.

In addition to signing and ratifying the Mine Ban Treaty, Myanmar must guarantee assistance and support for the often extensive rehabilitation that landmine victims require for recovery. The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction noted in a 2015 article on landmines in Myanmar that people disabled by landmines are, as a result of their injuries, “poorer than the rest of the community and have a lower level of education. They are also more isolated and less integrated into local society, facing discrimination and stigma,”[57] as is likely to be the case with the survivors included in this report.

Health Services Access Denial

“They [Myanmar security forces] threatened that if they could catch injured people, they would slit their throats.”

Abu Tayub, 25

Myanmar is party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESR), a treaty which requires governments to guarantee the “highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.”[58] This covenant, which the government of Myanmar ratified in 2017, requires states to “ensure the right to access health facilities, goods, and services on a non-discriminatory basis.”[59]

Many survivors of the August 2017 attacks evaluated by PHR reported that they did not have access to medical care, despite facing life-threatening injuries. The lack of timely access to medical services and denial of care constitutes an infringement of the Rohingya’s right to health, as well as a major violation of universally recognized principles of medical ethics.

Several survivors said they had received only rudimentary medical services from local medical clinics with limited resources to treat their injuries, such as wound bandaging and over-the-counter pain med-ications. Many did not get proper medical treatment at all and instead sought treatment from local tra-ditional healers or treated themselves using herbal remedies like turmeric. These remedies were clearly insufficient to treat the life-threatening injuries Rohingya suffered. Several of the survivors said that they had either directly or indirectly heard that medical personnel in Myanmar were compelled to re-port injured people to the Myanmar authorities.

“They [Myanmar security forces] threatened that if they could catch injured people, they would slit their throats,” said Abu Toyub (Profile 25).[60]

As a result of the lack of medical treatment, 17 of the 43 disabled survivors interviewed and physically examined by PHR had to be carried into Bangladesh, while three could walk, but only with assistance. It was only once in Bangladesh that they received adequate medical treatment. Delays in medical attention resulted in overall poor health outcomes, increased complications, including infection, and less recovery of limb function and higher levels of immobility and disability among victims. Two survivors whose wounds became infected while hiding eventually required amputation of their limbs. One gun-shot wound survivor had a recurring limb infection that PHR medical experts suspected was due to an infection that extended from their skin to the bone due to an untreated wound. Bone infections require immediate treatment and months of antibiotic therapy and when inadequately treated often result in permanent limitations in limb movement, changes in sensation in the affected limb, and limb pain. Many survivors also said they still suffered chronic limb pain months after the attacks. Such pain can sometimes result from the delayed or inadequate management of acute pain, wounds (muscle, ligament, nerve, skin, and bone injury), and complications of the original physical injury, such as infections.[61]

Photo: Salahuddin Ahmed for Physicians for Human Rights

As noted above, the Rohingya have long had inadequate and discriminatory access to health care within Myanmar. But the failure to deliver medical care in an emergency situation where an injury is a genuine threat to a person’s life is a major violation of the principles of medical ethics. The World Medical Association, an independent global confederation of medical providers, calls for medical providers to make the health of their patient their first consideration, and not to allow considerations of creed, ethnic origin, or nationality to interfere with their care for patients.[62]

There are indications that discriminatory deprivation of medical services to Rohinyga remaining in Myanmar is worsening, according to reports from aid groups working there. Rohingya have to pay more for treatment, are kept in segregated wards, and even have difficulty obtaining blood donations because of state-sanctioned discrimination against them.[63]

Both the denial of emergency care during the August 2017 attacks as well as ongoing discriminatory access to health care services for the Rohingya in Myanmar constitute serious violations of the right to health.

Deprived of the Ability to Work

“How can I [farm again]? I have to try to do as much as I can, but I can’t hold anything firmly and so I won’t be able to work.”

Abu Tayub, 25, landmine injury

The ICESR also guarantees that all people have the “right of self-determination,” including the right to “freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.” It also decrees that “in no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence.” This principle is further reinforced by Article 6, which enumerates the right to work, meaning “the right of everyone to the opportunity to gain his living by work which he freely chooses or accepts.” Denial of this right has a ripple effect on a series of other human rights, such as the right to an adequate standard of living.[64]

The Rohingya who remain in Myanmar are already denied this right: the government has continued to target Rohingya by shelling their villages[65] and forcing them to live in camps for internally displaced people, where their freedom of movement and association is highly restricted, depriving them of their ability to pursue a livelihood through farming or other means.[66]

However, even under more hospitable conditions, having a physical disability would make life in rural northern Rakhine state – which was home to all 43 survivors whose stories are recounted in this report – challenging; in a region where farming, fishery, and aquaculture are the main sources of livelihood,[67] amputees or those who no longer have full use of their limbs will clearly be unable to realize their right to work. A survey of four northern Rakhine townships found that 54 percent of households sold crops, livestock, aquaculture, or fishing products in the 12 months before the survey, while casual farm labor accounted for more than a quarter of people’s income.[68] Forty-four percent of people in Rakhine state live below the poverty line, compared to the national average of 26 percent.[69] Subsistence farming is a vital part of everyday life.

Fifteen of 19 survivors who gave information about their or their family’s source of income said they made their money farming, fishing, or doing other types of physical labor. Two survivors were teachers (although one said he also made money by working on the family farm) and two were students. The remaining 24 did not state their source of income.

Given the crucial role of physical labor in the predominantly agricultural economy of rural Myanmar and the purposeful official barriers that the Rohingya face in accessing health services there, these potentially long-term disabilities will change the course not only of the survivors’ lives, but their livelihoods as well. The World Food Programme has noted that while most of Mynamar’s residents struggle to access “sufficient, safe and nutritious food,” people with disabilities face even greater challenges due to “discrimination, including customary laws and traditions.”[70]

A Myanmar government survey published in 2012 revealed that 85 percent of the country’s people with disabilities were unemployed and relied on “casual labor” for their livelihood. As a result, persons with disabilities in Myanmar “are more likely than non-disabled persons to be poor, uneducated, unemployed, to live in poor housing, to be landless, to die prematurely, to have food insecurity, to be unable to access public information, to be excluded from public places, and to be ignorant of their rights.”[71]

The poor employment prospects of disabled Rohingya if and when they have the opportunity for safe and voluntary return to Myanmar are compounded by long-standing barriers to education. Schools are segregated in Rakhine state, and travel bans have prevented Rohingya schoolteachers from accessing government-run teacher training programs, meaning that many Rohingya teachers do not have higher education.[72] This limited and segregated access to education – in and of itself a violation of the right to education guaranteed in the ICESR – has been the status quo for many years.[73] In addition to guaranteeing education, ICESR mandates a right to “technical and vocational guidance and training programs.”[74] Without access to adequate schooling and training programs, Rohingya returnees to Myanmar are unlikely to acquire skills that could help mitigate the impact of their disability on their employment prospects and standard of living.

Disability Rights

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) guarantees the rights of disabled people not to be discriminated against, to be actively included in society, and to be guaranteed equal opportunity and accessibility. The CRPD also calls on governments to “promote vocational and professional rehabilitation, job retention and return-to-work programs for persons with disabilities.”[75]

In addition to allowing the independent investigation and prosecution of those responsible for past crimes against the Rohingya, the Myanmar government has forward-looking obligations toward the disabled. As noted above, even able-bodied Rohingya continue to face discrimination in accessing education, health care, and employment opportunities in Rakhine state. If and when the Myanmar government creates the conditions for safe and voluntary return of Rohingya survivors from Bangladesh, disa-bled returnees are likely to face even greater barriers.

Myanmar’s Response

To date, the Myanmar government has denied scrupulously well-documented allegations of widespread and systematic violence by security forces who targeted the Rohingya. It has also blocked international human rights organizations and the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Myanmar, Yanghee Lee, from accessing the country to investigate these allegations. The Myanmar government has also made no public mention of the disabilities inflicted upon thousands of Rohingya by the targeted violence of August 2017. The Myanmar government has also failed to acknowledge its obligation to provide rehabilitation and reparations for disabled Rohingya civilians or to create conditions for their safe and voluntary return.

As of December 2018, the Myanmar government appeared to be cementing segregation by forcing the minority of Rohingya who remain in Myanmar to live in separate and closely monitored camps.[76] Humanitarian aid groups had been banned from providing much-needed food and other assistance to the region[77] and renewed military operations – including the shelling of villages inhabited by civilians – had displaced an additional 5,200 Rohingya in Rakhine state.[78] These operations, in response to alleged attacks by the Arakan Rohingya Solidarity Army (ARSA), have also included official restrictions on the amount of food that Rohingya can transport to their villages due to allegations by military authorities that Rohingya village food stores supply ARSA insurgents.[79]

In September 2018, the UN Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar found that the crimes carried out by security forces against the Rohingya in August 2017 should be investigated and prosecuted as genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.[80] In response to these findings, the UN Human Rights Council voted overwhelmingly to extend the mandate of the fact-finding mission so that it could continue gathering evidence for eventual use in criminal proceedings against the Myanmar government.[81] The fact-finding mission recommended that Myanmar be prosecuted by the International Criminal Court (ICC). Though Myanmar is not party to the Rome Statute, which established the ICC, the UN Security Council can refer a non-signatory to the ICC for investigation. However, Russia and China reportedly oppose such proposals.[82] The fact-finding mission also recommended other avenues for prosecuting Myanmar officials, such as an ad hoc international tribunal, and created an independent mechanism “to build on the important work of the Fact-Finding Mission by collecting, consolidating, preserving and analyzing evidence of the most serious crimes and violations of international law committed in Myanmar since 2011.”[83]

Myanmar has refused to cooperate with international attempts to investigate the alleged crimes and has failed to establish truly independent mechanisms to do so within the country. A government-backed commission announced in December 2018 that it had found no evidence to confirm the UN fact-finding mission’s allegations.[84] Eight previous Myanmar-led commissions have failed to find systemic wrongdoing on the part of the security forces,[85] and there is little hope that members of the new council will be impartial. As of January 2019, Myanmar continued to bar entry to UN Special Rapporteur on Myanmar Yanghee Lee.[86]

Myanmar’s refusal to engage with the international community has been reinforced by a crackdown on domestic civil society and media outlets. Two Reuters journalists were arrested for reporting on the massacre of 10 men and boys from a Rohingya village. In September 2018, they were sentenced to seven years in prison. The Myanmar government freed the two journalists on May 7, 2019 after relentless international pressure for their release.[87] The Myanmar government has blocked journalist access to Rakhine state and has denied allegations of human rights abuses confirmed by other media outlets.[88] Most humanitarian organizations have been barred from working in northern Rakhine state.[89] Barring journalists and humanitarian organizations not only harms the civilian population of Rakhine state by depriving them of services, but eliminates potential witnesses to any past or future crimes, leaving civilians even more vulnerable.

In late October 2018, officials from Myanmar and Bangladesh announced an agreement to begin repatriation of Rohingya currently living in Bangladesh back to Myanmar.[90] UN officials condemned the plan,[91] noting that security risks and living conditions for Rohingya within Myanmar are still dire. Many Rohingya inside Myanmar are forced to live in government-run camps for internally displaced persons, where strict travel restrictions and curfews are a daily reality.[92] Plans to relocate the displaced to government housing far from the Rohingya’s native villages have been criticized for attempting to further cement segregation.[93] The government of Bangladesh is pursuing plans to relocate up to 100,000 Rohingya currently in Cox’s Bazar to the nearby uninhabited island of Bhashan Char.[94] UN Special Rapporteur Yanghee Lee in March 2019 publicly questioned “whether the island is truly habitable.”[95]

Conclusion

Based on the accounts in this report of Rohingya women, men, and children suffering severe disabilities as a result of the 2017 attacks by Myanmar security forces, it is clear that Myanmar security forces perpetrated grave human rights violations against the Rohingya, and that Myanmar’s actions should be investigated per the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court or before other ad hoc tribunals that have jurisdiction to try individuals for serious international crimes, including crimes against humanity and genocide. Additionally, Myanmar should be held to account for other violations of civil and political rights, the right to health, the right to work, and the unlawful use of landmines against civilians.

Moreover, the stories and medical documentation detailed in this supplemental report underscore the importance of enforcing Myanmar’s forward-looking obligations to the Rohingya people. For many years, the Rohingya have been denied the right to citizenship and the right to self-identify as Rohingya, and they have been routinely denied or given discriminatory access to health care services, employment opportunities, and education. This situation continues within Myanmar today, and is bound to confront returnees with long-term disabilities with an even more daunting reality, since their inability to do physical labor will limit their economic prospects.

The Myanmar government is clearly unwilling to investigate, acknowledge, and hold accountable those people responsible for these crimes, or to stop discriminatory practices against the Rohingya. Therefore, international actors must help bring justice to the Rohingya. Among other measures, they must put mechanisms in place to ensure that Rohingya disabled in the attacks receive reparation for the harms they have sustained, and that, wherever they reside, they have the possibility to thrive.

Recommendations

To the United Nations Security Council:

- Implement the recommendations of the UN’s Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar, including:

- Investigate and prosecute crimes committed by the Myanmar government by referring the situation to the International Criminal Court, or by creating an ad hoc criminal tribunal;

- Impose an arms embargo against Myanmar until independent international observers certify that the Myanmar government no longer supports or perpetrates gross human rights violations against the Rohingya and other minority groups and vulnerable populations in Myanmar;

- Adopt individual sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, against responsible Myanmar officials, including at the highest levels of government and the security forces;

- Support safe, dignified, and voluntary repatriation of refugees only with assurances and international monitoring of safety and individual choice, with explicit human rights protections, including citizenship, for the Rohingya;

- Create a trust fund for victim support, including psychosocial support, legal aid, livelihood support, and other means of assistance.

- Convene a session dedicated to the commission of atrocity crimes in Myanmar, with a specific focus on genocide prevention tools that should guide UN policy toward Myanmar in order to mitigate future risks to Rohingya and other groups in the country.

To United Nations Member States:

- Create an internationally-funded mechanism to provide the resources necessary for sustained treatment, rehabilitation, and vocational training for Rohingya victims physically disabled in the 2017 attacks.

- UN member states who are party to the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (“Genocide Convention”) and who have already recognized the crimes against the Rohingya as genocide – including Canada and Malaysia – should file complaints to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for the Myanmar government’s violation of the Genocide Convention and press the ICJ to seek reparations.

To the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Disability and the UN Division for Social Policy and Development, which oversees enforcement of the Covenant for the Rights of People with Disabilities:

- Support the creation of a systematic assessment of the Rohingya population disabled in the Au-gust 2017 violence in order to triage the most serious cases for immediate treatment and for longer-term rehabilitation and vocational training with transition to economic dependence, and psychosocial support of those individuals.

- Urge the government of Bangladesh and UN member states supporting Bangladesh’s humanitarian support for Rohingya refugees to respect their obligations under Article 11 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which requires state parties to “ensure the protection and safety of persons with disabilities in situations of risk, including situations of armed conflict, humanitarian emergencies, and the occurrence of natural disasters.”

- Urge only safe, dignified, and voluntary repatriation of refugees, including those Rohingya with dis-abilities, and only with assurances and international monitoring of safety and individual choice, with explicit human rights protections, including citizenship, for the Rohingya, in line with Article 15 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which requires state parties to “take all effective legislative, administrative, judicial or other measures to prevent persons with disabili-ties, on an equal basis with others, from being subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

- Urge UN member states supporting international accountability efforts for Rohingya victims and survivors of the August 2017 violence to respect their obligations under Article 13 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which requires states to “ensure effective access to justice for persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others.”

- Urge the government of Bangladesh and UN member states supporting Bangladesh’s humanitarian support for Rohingya refugees to respect their obligations under Article 16 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which requires state parties to “take all appropriate measures to promote the physical, cognitive and psychological recovery, rehabilitation and social reintegration of persons who become victims of any form of exploitation, violence or abuses, including through the provision of protective services.”

To the Government of Myanmar:

- Cease segregation of and human rights violations and discrimination against the Rohingya people.

- Appoint an independent third party to investigate and prosecute human rights violations and crimes against humanity committed during the August 2017 attacks as well as other violations committed against the Rohingya and other religious and ethnic minorities in Myanmar.

- Grant access to United Nations officials, agencies, and other international organizations to investi-gate human rights violations in Myanmar, particularly in Rakhine state.

- Provide assistance to all Rohingya people with disabilities, including those disabled in the violence of August 2017, including:

- Creation of a trust fund or other financial mechanism to provide sustained support to those who were injured in the August 2017 attacks and are unable to achieve financial independence as a result;

- Provision of funding for free and comprehensive long-term access to health care and rehabilitative services, with the explicit aim of promoting vocational and professional rehabilitation; and

- Creation of return-to-work programs designed for people with disabilities, and full access to and promotion of educational opportunities for the disabled.

- Guarantee safe, dignified, and voluntary repatriation of Rohingya refugees by explicitly protecting their human rights, including with guarantees of citizenship.

To the Governments of the European Union and the United States:

- Expand existing financial sanctions against the Myanmar government and military, and specifically link the lifting of those sanctions to measurable benchmarks, including the end of human rights violations, discrimination, and segregation targeting the Rohingya and to cooperation with international mechanisms for accountability.

- Expand visa bans and asset freezes to include all senior Myanmar security officials for whom the United Nations Fact-Finding Mission and domestic and international human rights organiza-tions have compiled convincing evidence of those officials’ complicity in grave rights violations against the Rohingya people.

- Impose broader trade sanctions on specific industries within Myanmar, including the loss of tariff-free access to European Union (EU) markets by revoking Myanmar’s EU trade access via the “Everything But Arms” agreement of the Generalised Scheme of Preferences.

- Impose foreign investment bans on businesses with proven close links to the Myanmar military.

- Support resolutions in national and international fora to protect Rohingya refugees from forced repatriation, and to ensure the safe, dignified, and voluntary return of displaced persons. Maintain or expand current suspensions on military relations between Myanmar and the EU or the United States, and specifically condition the full resumption of military relations on specific human rights and accountability benchmarks, including those referenced and recommended in this report.

Profiles

Profile 1: Mohammad Erfan, a 15-year-old male

- Impairment: Gunshot wound resulting in amputation of arm. Treatment delayed due to violence.

- Disability: Unable to perform basic tasks, including manual labor in an agricultural setting without a prosthesis.

In late August 2017, Mohammad Erfan was at home with nine family members in the mid-afternoon when security forces and Rakhine Buddhist civilians surrounded his village. The civilians entered homes and looted valuables. Anyone who resisted or ran away was attacked by security forces, who then began burning down homes.

Erfan ran into the forest with his family and was shot in the left upper arm. He recalled running for a bit and then fainting. When he regained consciousness, he couldn’t see anyone and his village had been destroyed. He had not seen his parents since, but found an uncle and two siblings in the forest near his village. They spent two months there, too afraid to leave, but eventually they traveled to Bangladesh. Erfan had no treatment for his arm and was unable to move it. He had severe pain, but no fever or signs of infection during those two months.

At the border, Erfan was referred straight to the hospital where his left arm was amputated, leaving a stump. He still suffered from itching and ghost limb sensations. His uncle had found his wife and children and had gone to stay with them, leaving Erfan alone in the camp. At the time of the interview, he thought he would be able to leave the hospital soon but did not know how he would find work or do anything without his arm.

PHR Medical Evaluation

Erfan had a total left upper extremity amputation with good granulation (re-growing) tissue around a still open 4 cm area at the stump. Otherwise, the wound was clean, dry, and intact. A review of medical records included labs and chest X-ray which were all unremarkable and a simple surgical report indicating he had an amputation but not noting the reason it was needed.

Profile 2: Fozol Korim, a 28-year-old male

- Impairment: Gunshot wound resulting in bone fracture, nerve injury, rotator cuff tear and limited ability to lift and move arms. Treatment delayed due to violence/incorrectly treated.

- Disability: Unable to perform basic tasks, including holding his newborn child.

One night in September 2017 at around 4 a.m., Fozol Korim heard gun shots in his village of Mirullah. He went outside and saw Myanmar security forces about 500 meters away firing weapons. On the other side of the road, security forces were trying to surround the village and were burning houses. He woke his wife and four children and they ran into the forest.

At around 8 a.m., the security forces started firing randomly into the forest, knowing villagers were hiding nearby. Korim’s nephew was shot in the chest and died immediately. His cousin was shot in the back of the head and died immediately. Korim was shot in the left upper back area. He fell, losing blood and feeling weak. The family carried him for more than four days to Bangladesh.

He went immediately to a hospital where little was done for him. An X-ray showed a broken bone. Korim still could not lift any weight with his left arm and felt very weak. He had a newborn child, who he couldn’t carry in that arm. He had persistent aching chest pain and fatigue.

PHR Medical Evaluation

Korim’s exam was consistent with his narrative. His weakness was obviously visible and represented a more than superficial injury to the limb’s bone, nerves, and muscles, which includes a rotator cuff tear.

Korim had an entry and exit bullet wound in the left upper back just over the superior scapula (shoulder bone). The entry wound is about 1.5 cm and circular. The exit wound is oval-shaped with the medial (middle) area appearing with a scab and an extended lateral oval area, consistent with a bullet injury. The scab area, according to the patient, is very itchy and he scratches it regularly. He had no history of bone or soft tissue infection or pus draining from the limb. The wound appeared clean, dry, and intact and was forming a small scab. He had no pain when examining the wound by the examiner’s hands or no tenderness to palpation. His scapula (shoulder bone) and clavicle (collar bone) appeared intact.

Korim had significantly limited range of motion and could not lift his left arm above his head and has limited posterior (backward) movement, a severe limitation that constitutes a disability (per WHO definitions).[96] The length of time since the initial injury, coupled with the lack of progress made over time, classifies this as a long-term, and likely permanent, disability.

Profile 3: Abdul Wahid, a 6-year-old male

- Impairment: Gunshot resulting in leg injuries, causing inability to walk without a limp or run. Treatment delayed due to violence.

- Disability: Unable to perform basic tasks including walking and rice farming.

Abdul Wahid’s family were rice farmers in the village of Morikorum. Wahid’s father said the Rohingya had experienced increasing persecution and had not been allowed to leave their town to buy things. On September 3, 2017, after already hearing that the military was attacking all nearby Muslim villages, the family saw Rakhine Buddhist civilians and security forces entering the village. They ran in the forest and walked for two days, when they heard gunshots nearby. Wahid was hit in the left leg, but nobody else in the group was hit.

Wahid remembered being shot but then fainted. His father carried him another two days through the forest to Bangladesh. Wahid was bleeding from several wounds in his scalp and on the left side of his leg, buttocks, and back. His leg was shattered. In Bangladesh, he had surgery and spent a month in the hospital before returning to the camp on crutches. He could walk independently but had a limp and could not run.

PHR Medical Evaluation

(Patient’s) wounds were significant and consistent with the manner of injury described in the history, specifically a projectile injury, either from a shotgun or ricochet of bullet fragments.

Wahid had several scars over his left leg, hip, and buttocks and on his scalp that appeared a few months old. He had a valgus deformity (bone angled away from leg) on his left leg and walked with a limp. He had a 3 cm stellate burst (star-shaped) scar with an 8 cm surgical wound superior to (above) it over the anterior (front) left mid-shaft of the leg. He also had similarly aged wounds of 0.5 to 2 cm over the right superior tibia area (top of lower part of leg) and the medial (middle) aspect of the right knee. He also had a 0.3 cm right frontal scalp wound just past the hairline. He had two wounds to the left buttock consistent with a projectile injury (circular) and a 3.5 cm by 0.75 cm healed wound just superior to (above) the penis in the groin area.

Profile 4: Mohammad Eliyas, a 20-year-old male

- Impairment: Explosive blast resulting in deformities of left eye, loss of fingertips, and other hand injuries. Treatment delayed due to violence/untreated.

- Disability: Difficulty with any basic tasks with his hand, including gripping and loss of sight.

Mohammad Eliyas reported that his village, Landha Khali, was attacked on August 27, 2017 by Myanmar security forces. He was at home with 11 family members. As he heard shouting outside, Eliyas was hit by something hot and heard a loud explosion at the top of his house. He reported falling to the ground and being confused. He then recalled being picked up by his family and helped out of the house. At that time, he had pain in his right hand and left eye and also in his arms and chest. He could not see from his left eye thereafter. His house was full of smoke and flames, and smoke and flames were coming from other houses as well. His family led him out of the village and they walked to Bangladesh, which took two days.

Eliyas was sent to the hospital for his hand injuries, but no surgery was possible, and he had not seen medical staff about his eye. He reported that he could only see light and dark from his left eye, not shapes or colors. He also reported constant tearing which got worse if he went out during the day.

PHR Medical Evaluation

Eliyas’s physical examination revealed numerous injuries that are highly consistent with his account of blast injuries secondary to an explosive/incendiary device being detonated in or on his home. The injuries to his right hand revealed a traumatic loss of bone and skin that was imprecise and resulted in varying degrees of damage to his fingers. The multiple scars on Eliyas’s hands, arms, and chest were also consistent with multiple fragments from various types of materials impacting his body all at the same time.

Eliyas’s left eye revealed blurring of the perimeter of the iris from the 2 o’clock to 10 o’clock positions. This blurring included a loss of border between the sclera and iris and also included a brown ring of pigmentation. The sclera was injected (reddened) in the inferior half of the eye and the pupil appeared largely opacified and the border between the iris and pupil was not apparent.