Foreword

Dr. Şebnem Korur Fincancı

Chairperson of the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey, PHR Advisory Council

Dr. Metin Bakkalcı

Secretary General of the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey

Regardless of where we are, we are living in a reign of violence in which we can’t breathe. We are witnessing a global downward trend in terms of respect for fundamental human rights, freedom, democracy, and the rule of law. In most parts of the world, the human rights environment is radically transforming in a way that brings into question the basic concept of human rights: holding, possessing, claiming, and asserting rights legally as a human being. This deterioration in the human rights environment has accelerated over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nonetheless, hope and solidarity are always present. Otherwise, how could the last words of George Floyd be owned by millions of people in the United States and elsewhere in the world? Yes, we will come out of this dark period, thanks to the invaluable efforts against tyranny of large groups of people who cannot be silenced.

The report you are about to read, which documents unlawful use of force by law enforcement officers during Black Lives Matter protests in June and July 2020 in Portland, Oregon, is another effort that gives us reason to believe in a humane world that stands against violence, torture, and racism.

For 34 years, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) has documented abuse of force by governments and their security and police forces in countries around the world. Among many others, PHR worked closely with our organizations in Türkiye to document police violence against peaceful demonstrators and pressures on health care professionals during the 2013 Gezi Park protests in Türkiye.

This current report reveals that the violence exerted by law enforcement officers against peaceful demonstrators in Portland constitutes unlawful use of force that could amount to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.[1]

Health care workers are usually the very first witnesses of state violence throughout the world. Their caring and equally courageous efforts are brought to light once again, thanks to this report.

As their friends and colleagues from Türkiye, we extend our thanks to PHR for conducting this study and preparing this report, which is so invaluable for the people of the United States and the whole world, particularly for those subjected to state violence.

“We came out here dressed in T-shirts and twirling Hula-Hoops and stuff, and they started gassing us, so we came back with respirators, and they started shooting us, so we came back with vests, and they started aiming for the head, so we started wearing helmets, and now they call us terrorists. Who’s escalating this? It’s not us.”

Mac Smiff, Portland journalist and Black organizer

MSNBC, July 29, 2020

Executive Summary

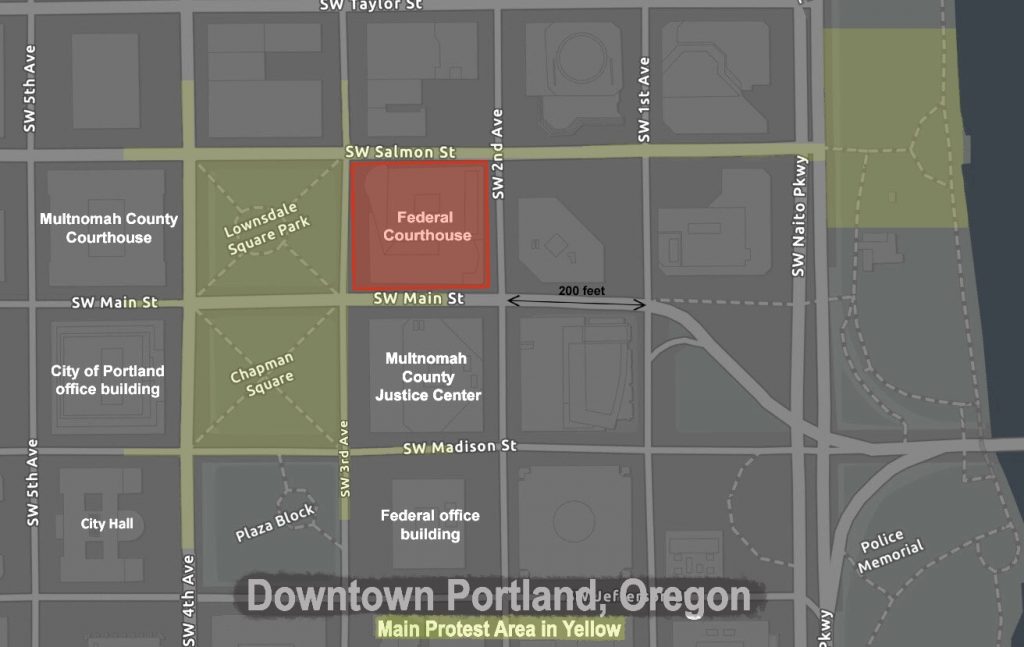

The May 25, 2020, in-custody police killing of George Floyd sparked a wave of public demonstrations across the United States and around the world against police violence and racism. Thousands of residents in Portland, Oregon organized and joined in large demonstrations under the banner “Black Lives Matter” (BLM). While these demonstrations – many of which took place in front of the Multnomah County Justice Center (“the Justice Center”), the adjacent Mark O. Hatfield United States Courthouse (“federal courthouse”), and the city parks of Lownsdale and Chapman Squares in downtown Portland – were overwhelmingly peaceful, a small minority of protestors set small fires and broke into storefronts.

As early as May 29, President Donald Trump made public statements expressing eagerness to send the military to U.S. cities to respond with force to the demonstrations. On June 26, President Trump issued an Executive Order to send federal officers to cities around the country with the stated purpose of protecting monuments, statues, and federal property. On July 1, federal officers emerged for the first time from the boarded-up federal courthouse and fired pepper balls at demonstrators. Most officers were clad in either black or camouflage military uniforms, without clear identification of their agency or their name. Although the demonstrations had dwindled to a couple of hundred people by July 3, the arrival of federal troops reignited the protests. The month of July saw nightly protests of thousands of people being met with massive barrages of tear gas, rubber bullets, and other crowd-control weapons fired by Portland police and federal agents.

A Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) investigation conducted in Portland from July 24 to July 31, 2020 examined evidence of excessive use of force by Portland Police Bureau (PPB) officers and federal agents in July 2020, through a focus on both attacks against volunteer protest medics and the medics’ own experiences treating injured protestors. The team also examined whether there was interference with emergency medical assistance and whether in any cases medics were specifically targeted. The team interviewed 20 health professionals, former emergency medical technicians (EMTs) and paramedics, and other volunteers who regularly worked as medics at the Portland protests in June and July 2020. PHR interviewed in person and conducted targeted medical examinations of four medics who had sustained clinically significant injuries from PPB and/or federal agent use of force. PHR also spoke with three injured medics by phone, each of whom provided photographic documentation of their injuries. PHR interviewed in person and conducted medical examinations of two protestors who sustained injuries during the weekend of July 24-25, and PHR conducted phone interviews with two protestors injured that weekend who provided photographic documentation of their injuries. In addition, PHR spoke with six elected Portland, county, and state officials who had attended the demonstrations, four leaders of Black activist and community organizations coordinating and providing leadership for the demonstrations, and representatives of legal organizations. Finally, PHR interviewed four current paramedics with American Medical Response, Inc. and four Portland Fire Department and county officials in charge of emergency medical response. All interviews were completed between July 25 and August 10, 2020.

This study’s findings provide evidence that PPB officers and federal agents engaged in a consistent pattern of disproportionate and excessive use of force against both protestors and medics over the course of June and July 2020. Medics further reported treating an increasing number of serious injuries among protestors from kinetic impact projectiles following the arrival of federal agents on July 1. Volunteer medics experienced and witnessed indiscriminate attacks by both PPB officers and federal agents. In some cases, medics reported that these attacks appeared to be specifically targeting medics, including the use of tear gas and projectiles. A number of medics sustained serious injuries while providing medical assistance to protestors due to the use of force by PPB officers and federal agents.

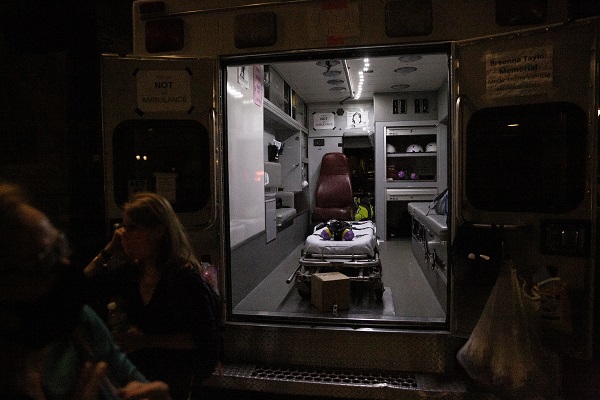

PHR also documented that, except for rare reported instances, paramedics affiliated with the PPB and Fire Department did not provide medical care to injured protestors. Furthermore, because the PPB deemed the area unsafe, official ambulances were prevented for much of July from arriving within a perimeter of several blocks outside the downtown protest site to assist and transport injured demonstrators to emergency rooms. This left a gap that civil society had to fill. While there did not appear to be a consistent pattern of law enforcement destruction of medical supplies, there were a few reported incidents.

The U.S. Department of Justice has not developed national guidelines detailing the lawful use of so-called less-lethal weapons, and U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) national policy on use of force also does not contain any detailed guidance related to the lawful use of these weapons.[2] The 1990 UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials has limited mention of “less-lethal” weapons, focusing on the use of firearms. However, the 2020 UN Human Rights Guidance on Less Lethal Weapons in Law Enforcement (“UN Guidance”) provides more detail on how weapons may or may not be used in order to respect the human rights principles of necessity and proportionality and the U.S. government’s obligation to prevent cruel or inhuman treatment and protect the right to life. Potentially unlawful use of these weapons should not be considered to comply with the U.S. constitutional standard of reasonableness, that is, that the use of force is “objectively reasonable” in light of the specific circumstances.[3] When comparing the cases that PHR documented, there were many incidents where potentially unlawful use of “less-lethal” weapons occurred in Portland, including: use of batons on people not engaged in violent behavior; use of chemical irritants without sufficient toxicological information made available for treatment by medical responders; irritant-containing projectiles fired at individuals, including at the head and face; and kinetic impact projectiles fired at the head and face. The use of crowd-control weapons against those only passively resisting dispersal was also reported to cause mental pain and suffering to demonstrators, resulting in potential psychological trauma. Such use represents unlawful use of these weapons and may constitute cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

The volume and type of weapons deployed could be expected to require emergency medical attention. Yet, there were no measures to coordinate between the county EMS, city Fire Department, city police and contracted ambulance service to prevent a gap in services, with the result that civil society had to try to fill this gap. Meanwhile, volunteers seeking to provide assistance were also threatened and attacked by local police and federal forces.

The UN Guidance states that when the government is deploying crowd-control weapons in a protest setting, the government is obligated to ensure that protestors have timely access to emergency medical services, including by actively protecting medical personnel, whether they are acting officially or as volunteers. The DHS use of force policy of 2018, which states that medical care should take place “as soon as practicable following a use of force and the end of any perceived public safety threat,” is not in compliance with these international standards and unacceptably increases the health risks for protestors.[4] According to the cases documented by PHR, the government did not actively protect volunteer medics, even those who were clearly marked and offering particular aid to people who had been incapacitated by serious injuries. Moreover, the official ambulance service, when called, was often not allowed to come directly to even seriously injured protestors at the downtown protest site, as the PPB declared the area unsafe.

Many people PHR interviewed believed that the combination of potentially unlawful use of “less-lethal” weapons and failure to ensure and protect emergency medical services discouraged people from attending peaceful assemblies who would otherwise have done so. The repeated use of excessive force escalated tensions between demonstrators and law enforcement. To date, law enforcement officials who seriously injured demonstrators with excessive use of force or who have overseen such use have not been held accountable.

PHR recommends the following actions to the City of Portland:

• Establish an official oversight body of lawyers and others empowered to monitor and observe each demonstration, and then report to the City Council and police oversight board. Official ongoing monitoring at protests is essential;

• Create a safe zone very near to the protest area where medical personnel have safe access to attend to any injured person, whether acting officially or as volunteers, along with a safe way to transfer patients from the protest area to the safe medical area;

• Prohibit police crowd-control tactics that create a disproportionate risk of serious injury or death, including the use of rubber bullets and “kettling” (confining groups of protestors in a small area);

• Release reports on police use of force that explain in each instance why the use of force was necessary and proportionate for each deployment of crowd-control weapons or firearms and which measures were taken to ensure access to emergency medical services;

• Require police to be equipped with body and dashboard cameras and clear identification of names;

• Facilitate an independent review process accessible to people who have been subjected to the use of force, such as an evaluation similar to a Department of Justice pattern or practice study.

PHR makes further recommendations for the U.S. Congress, U.S. Department of Justice, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Oregon Attorney General’s office, and the Multnomah County EMS and Portland Fire Department, which are detailed later in this report.

Background

Local Police Responses to Nationwide Demonstrations Supporting Black Lives Matter in the United States

The killing of George Floyd in police custody in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, following that of Ahmaud Arbery by three white men in Atlanta and Breonna Taylor by police officers in Louisville, precipitated a wave of public demonstrations across the United States and around the world. These killings further compounded outrage about the disproportionate rates of COVID-19 infection and death among Black and other communities of color. In response, in the United States, hundreds of thousands of people of all races joined in public demonstrations to demand an end to systemic racism, widespread racial inequality, and police violence. On June 6 alone, half a million people in nearly 550 places across the United States turned out to show their support for the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement.[5]

In the United States, these demonstrations were met with varied local police responses. In cities such as Camden, NJ, Flint, MI, and Newark, NJ, police officers joined with protestors in peacefully marching.[6] In other cities, police in full riot gear confronted demonstrators, volunteers providing medical assistance (“medics”), legal observers, and journalists, while brandishing shields and batons and deploying a barrage of chemical irritants and kinetic impact projectiles (KIPs). In some areas, local police presence was augmented by federal agents, as was the case in Portland, Oregon from July 1 to July 29. Although there were some instances of vandalism and violent acts, the overwhelming majority of demonstrations in all U.S. cities through these months were peaceful.[7] Nonetheless, scores of protestors were injured as a result of police use of excessive force, often in peaceful settings. In many documented instances, such attacks were used as the first response against peacefully assembled crowds.[8] Nationwide, between May 26 and July 31, 2020, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) confirmed 115 cases of head injuries documented by news and social media from rubber bullets, other impact munitions, and tear gas canisters.[9]

Provision of Medical Assistance and Aid to Injured Protestors in U.S. Protests

The UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials specify that when law enforcement officials resort to force in the context of protests, they “shall ensure that medical assistance shall be rendered to any injured or affected person at the earliest possible moment.”[10] These guidelines impose a positive obligation on officials to ensure effective access to medical care and transport. Since U.S. protests began in May 2020, such official medical assistance at the site of protests has often been absent or withheld. Therefore, informal networks of volunteer medics and civil society organizations have often been required to rise to the occasion and tend to the injured.

These networks of volunteers, often referred to as “street” or “protest” medics,[11] include emergency medical technicians (EMTs), paramedics, physicians, and nurses, as well as lay-people with first aid training, to support protestors’ health needs. Many function as the first point of contact for assessment and treatment of a wide variety of injuries. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, many also provide masks and hand sanitizer to protestors. Other medics stay close to medical supply tents or vehicles to provide more advanced levels of care and assist with transport as necessary to urgent care facilities. In the face of the use of chemical irritants and KIPs over the past few months in some cities, many medics have provided eye washes to help remove chemical irritants from tear gas and pepper spray and have treated contusions, fractures, and lacerations from batons and projectiles.

Most medics wear clear markings and universally recognizable insignia to identify themselves as medical volunteers. These include red crosses and “MEDIC” markings on helmets, jackets, backpacks, sleeves, and other visible areas. Some clinicians wear white coats to signal their ability to provide medical aid. To date, there have been no systematic investigations of police treatment of volunteer medics, despite these individuals rendering assistance in many different U.S. cities. There have, however, been documented incidents of police injuring medics who are visibly well-marked, as well as damaging medical supplies and medical posts with clear signage. Human rights organizations and media outlets documented in May and June 2020 local police attacks on medics resulting in injuries in, at a minimum, Seattle, WA, Columbus, OH, Minneapolis, MN, Asheville, NC, Austin, TX, and Tampa, FL.[12]

For more than three decades, PHR has documented the health harms caused by so-called less-lethal crowd-control weapons (CCWs) like tear gas, stun grenades, pepper balls, rubber bullets, and other impact munitions. These CCWs are defined as “offering a substantially reduced risk of death when compared to conventional firearms.”[13] Less lethal does not mean non-lethal. PHR has reviewed cases upon cases of serious injuries, disability, and death from misuse of CCWs around the world, including in Bahrain, Panama, South Korea, Turkey, and multiple other countries. Projectiles, when fired at close range or directly at people’s heads, necks, or chests, have caused loss of eyes, perforated chests, brain damage, cardiogenic shock, and even death. They should never be used for crowd control against largely peaceful demonstrators. Law enforcement officials have a legal obligation to apply non-violent means before resorting to the use of force. “Less-lethal” weapons should only be employed against individuals committing violent acts if other means remain ineffective and when strictly necessary to obtain a lawful and legitimate law enforcement objective. Any use of these must be preceded by clear warnings. In the face of multiple serious injuries caused by police use of force in the U.S. Black Lives Matter demonstrations, there is a heavy burden of proof on these law enforcement agencies to show that these actions do not amount to excessive force that fails to comply with the international human rights principles of necessity, proportionality, precaution, legality, and accountability. The rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly are protected by the U.S. Constitution and international treaties ratified by the United States; any use of force deployed against demonstrators must be used as a last resort after carefully weighing all other enforcement options. In addition, police violence against clearly marked medics providing medical assistance in demonstrations, especially where official emergency services are not accessible, creates serious health risks that call into question whether the state is upholding the obligation to facilitate freedom of assembly and to protect the rights to life and health.

Portland, Oregon

Oregon has a long history of discrimination against Black people. This history has relevance to the events of 2020. Since white settlers began large-scale emigration into indigenous land in the 1840s, many of Oregon’s policies were explicitly discriminatory against Black people. The provisional territorial government prohibited Black people from entering or residing in Oregon, imposing punishment by whipping for breaking this law.[14] When Oregon joined the Union, the 1857 Oregon state constitution banned Black people from living in or holding property in Oregon, the only state in the Union with such a clause;[15] the clause was not formally removed from the state constitution until 1926.[16] Oregon did not ratify the 14th Amendment (Equal protection clause, ratified 1868) to the U.S. Constitution until 1973 and did not ratify the 15th Amendment (right of Black people to vote, ratified 1870) until 1959.[17] In the 1920s, Oregon had the highest number of Ku Klux Klan members per capita of any U.S. state.[18] Today, Portland is one of the whitest large cities in the country, with only 6.3 percent Black residents, while 72.2 percent of residents are white.[19] Recent county data show that Portland residents who live in communities of color east of 82nd Avenue have contracted COVID-19 at more than double the rate of people living in less diverse communities west of 82nd Avenue.

Before the 2020 protests, the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) had been found to engage in a pattern of excessive use of force. In the 2012 case U.S. v. City of Portland, the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon found that the Portland police had deployed unconstitutional and improper use of force against people experiencing a mental health crisis.[20] This case resulted in a 2014 Settlement Agreement on necessary police reforms, including, but not limited to, use of force, training, crisis intervention, officer accountability, and communication and transparency.[21] In 2015 and 2016, the U.S. Department of Justice found that the PPB was only partially compliant with nearly every provision of the agreement. In 2017, Mayor Edward Tevis Wheeler disbanded the city’s Community Oversight Advisory Board, a volunteer citizen board organized to monitor police reforms arising from the settlement, while also setting up a new system for monitoring compliance without community oversight.[22] Meanwhile, community groups, such as Don’t Shoot Portland, organized to advocate for police reforms after the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, including holding demonstrations[23] and supporting family members of people killed by police.[24]

In late May 2020, residents of Portland, Oregon organized and joined in large BLM demonstrations. These demonstrations, many of which took place in front of the Multnomah County Justice Center (“the Justice Center”), the adjacent Mark O. Hatfield United States Courthouse (“federal courthouse”), and the city parks of Lownsdale and Chapman Squares in downtown Portland, were overwhelmingly peaceful. On May 29, President Donald Trump made public statements expressing eagerness to send the military to U.S. cities to respond with force to the demonstrations. On June 26, President Trump issued an Executive Order to send federal officers to cities around the country, with the stated purpose of protecting monuments, statues, and federal property.[25] On July 1, federal officers came out of the boarded-up federal courthouse and fired pepper balls at demonstrators.[26] Most officers were clad in either black or camouflage military uniforms, without clear identification of their agency or their name. Within a week, Portland police announced that federal officers were making arrests and using tear gas against demonstrators. Although the demonstrations had dwindled to a couple of hundred people by July 3, the arrival of federal troops reignited the protests. The month of July saw nightly protests of thousands of people being met with massive barrages of tear gas, rubber bullets, and other crowd-control weapons fired by both Portland police and federal agents. On September 10, 2020, the mayor of Portland, who is also the Portland police commissioner, issued a directive ending the use of ortho-chloro benzylidenemalononitrile (CS) gas for crowd control.[27]

Timeline of Key Events in the Portland Protests from May through August 2020, as Documented in the Media

Late May 2020: Residents in Portland, Oregon organize and join in large, overwhelmingly peaceful Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

May 29, 2020: More than a thousand people participate in a vigil in North Portland and march to the Multnomah County Justice Center (“the Justice Center”) in downtown Portland, adjacent to the Mark O. Hatfield United States Courthouse (“federal courthouse”) and across the street from the city parks of Lownsdale and Chapman Squares, the site of most large demonstrations since then.

June 1: Authorities construct the first of several fences around the Justice Center that become the focus of nightly conflict between the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) and protestors until the fence is removed on June 26. Graffiti is sprayed on the neighboring federal courthouse and first floor windows are broken.[28]

June 26: President Trump issues an Executive Order to send federal officers to cities around the country, with the stated purpose of protecting monuments, statues, and federal property.[29]

July 1: For the first time, federal officers begin their nightly exit from the federal courthouse and fire pepper balls at demonstrators. Most officers are wearing black or camouflage military uniforms without clear identification of their agency or their names.

July 10: Portland police announce on social media that federal officers are making arrests and using tear gas against downtown demonstrators. President Trump formally announces that he has sent federal agents assigned to agencies within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the U.S. Marshals to Portland.

By July 17: Media sources report extensive use of chemical irritants and kinetic impact projectiles (KIPs) by federal agents and Portland Police Bureau (PPB) forces against multiple protestors over the prior weeks with numerous reported injuries. Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum files a lawsuit seeking a temporary restraining order barring the DHS and other federal agencies from seizing and detaining protestors.[30]

By July 22: Portland, Multnomah County, and state elected leaders are unified in their stated opposition to the presence of federal officers in Portland, [31] and the number of people participating in demonstrations at the federal courthouse surges to the thousands. Federal officials construct a fence around the federal courthouse.

July 25: More than 5,000 people join in the nighttime demonstration around the federal courthouse. New groups join the Black and other organizations participating in the protests, including groups such as the “Wall of Moms” (now Moms United for Black Lives), who come each night starting July 19 dressed in yellow and linking arms to form a physical barrier to protect protestors.[32] Other groups include the Disabled Comrade Collective, Wall of Vets, Wall of Dads, lawyers, teachers, health care professionals, chefs, and fire fighters. Groups such as Snack Bloc and Riot Ribs provide free food.[33]

July 29: Oregon State Governor Kate Brown and acting U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Chad Wolfe release statements that Oregon and the U.S. federal government have reached a deal to withdraw federal agents in exchange for an increased presence by Oregon State Police.

July 30-August 10*[1]: Small protests in Portland continue at diverse locations in the city, no longer centered downtown, with continued reported use of tear gas, mace, and force by the PPB and scattered acts of violence by some protestors.

September 10: The mayor of Portland, who is also the Portland police commissioner, issues a directive ending the use of CS tear gas for crowd control.[34]

Methods and Limitations

This report’s findings are based largely on a one-week investigation conducted by Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) in Portland, Oregon from July 24 to July 31, 2020, as well as phone interviews thereafter. The PHR team, consisting of the executive director, medical director, and a program staff member, examined evidence of excessive use of force by Portland Police Bureau (PPB) and federal officers in July 2020 through a focus on attacks against volunteer protest medics and the experiences of medics treating injured protestors. PHR researchers also examined whether there was interference with emergency medical assistance and whether in any cases medics were specifically targeted. In order to assess the nature and extent of purported abuses, the PHR team conducted interviews with medics providing assistance at the protests in front of the Multnomah County Justice Center and Mark O. Hatfield United States Courthouse, injured protestors who had received medical assistance from medics, and others who witnessed the reported incidents. The team also met with Portland, Multnomah County, and Oregon state elected officials, Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum and staff members, and representatives of legal organizations filing lawsuits on behalf of injured protestors. The team examined further background information from other sources, including the American Civil Liberties Union of Oregon, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and multiple traditional and social media sources.

Sampling Strategy

PHR used chain, or snowball, sampling to identify potentially eligible volunteer medics who provided assistance at the Portland demonstrations from May through July 2020. While this method is not designed to produce a representative sample of respondents, it constituted the only option that allowed for effective contact with eligible participants with whom outreach can be difficult. As there are high levels of caution and wariness among some medics, working through established medic networks and existing relationships helped quickly develop necessary trust among potential participants. The team sought to form as diverse a sample as possible by engaging with representatives from each of the main associations of street medics in Portland (e.g., Rosehip Medical Collective, Portland Action Medics, the Ewoks, the Witches, MEDBLOC), as well as representatives from OHSU4BLM, the medic group supported by the Oregon Health & Science University, key Black activist and community organizations, and local medical associations. Medics interviewed were all 21 years of age or older, had provided volunteer medical assistance at least within the month of July 2020, and, except for one interviewed medic, all had worn clear insignia identifying them as medics (e.g., red crosses) when working as medics during the protests. The protestors interviewed and examined had been injured by federal officers over the weekend of July 24-25 and had been treated by the medics we interviewed.

Human Subject Protections

The PHR researchers obtained written informed consent from each interviewee for the interviews, for audio-recording the interviews, and, in cases of injuries, for photo documentation. Before each interview, PHR ascertained whether the interviewee wished to remain anonymous. For those who requested this, PHR made every effort to protect their identities, using pseudonyms in this report and in notes. PHR’s Ethics Review Board provided guidance to and approved this study based on regulations outlined in Title 45 CFR Part 46.

Semi-structured Interviews

The physician researcher (Michele Heisler, MD, MPH) conducted in-person semi-structured interviews and, in the cases of people reporting injuries, targeted medical examinations between July 24 and July 30, 2020. She assessed interviewees for symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) using the abbreviated PCL-C, a six-item validated scale.[35] Through August 10, 2020, the PHR team interviewed by phone several additional medics and witnesses. In addition, PHR interviewed elected and other governmental officials and representatives of the Fire Department, official paramedics, and representatives of Don’t Shoot Portland, a leading Black activist organization coordinating demonstrations in Portland.

The team adapted health and human rights instruments used by PHR in similar settings where excessive force and attacks on health care workers have occurred. The semi-structured interviews of medics focused on details of any incident of violence the interviewee had experienced, their experiences caring for injured demonstrators, and the type and nature of injuries they had treated.

The PHR team interviewed 20 health professionals, former emergency medical technicians (EMTs), and paramedics, and other volunteers who regularly worked as medics over the two-month period during the 2020 Portland protests. PHR conducted targeted medical examinations of four medics who sustained significant injuries from PPB and/or federal agent use of force, whom we interviewed in person. PHR spoke with three injured medics by phone who provided photographic documentation of their injuries. PHR interviewed in person and conducted targeted medical examinations of two protestors who sustained injuries the weekend of July 24-25 and conducted phone interviews with two protestors injured that weekend who provided photographic documentation of their injuries. In addition, PHR spoke with six elected Portland, Multnomah County, and Oregon state officials who had attended the demonstrations, four leaders of Black activist and community organizations coordinating and providing leadership for the demonstrations, and representatives of legal organizations. Finally, PHR interviewed four current paramedics with American Medical Response, Inc. and four Portland Fire Department and Multnomah county officials in charge of emergency medical response. All interviews were completed between July 25 and August 10, 2020.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Drawing on interview notes and recordings, PHR researchers wrote case reports based on each interview of injured individuals. The clinician researcher provided diagnostic interpretations of the results of the targeted medical assessments and assessed the credibility of the accounts. PHR analyzed all interview transcripts thematically. The team also sought to verify interviews with reports from other witnesses, traditional and social media accounts, publicly available video footage, legal records, official medical records documentation, and other sources.

Limitations

As this was a rapid-response field investigation conducted over a short time (six days), it is subject to limitations in duration, scope, and access. The scope of the current investigation did not permit a full analysis of all written and video documentation of all events. It is also important to note that many demonstrators and medics who experienced injuries from local and federal security official violence did not seek formal care. Some accepted care from medics but refused to go to emergency departments, while others refused even medic assistance. Thus, documented accounts likely represent only a portion of total injuries. Moreover, PHR only interviewed a small number of medics. Their experiences may not generalize to a larger group. They do, however, illustrate the experiences of volunteer medics during the Portland demonstrations. This investigation should thus be considered a snapshot in time, with partial rather than complete community accounts and incomplete prevalence reporting of human rights violations. Notwithstanding these limitations, the study produced sufficient data to make informed conclusions and recommendations.

Key Findings

Physicians for Human Rights’ (PHR) investigation revealed a number of disturbing findings regarding the use of force by local and federal officers in Portland. Volunteer medics reported treating an increased number of serious injuries among protestors from kinetic impact projectiles (KIPs) over the course of July 2020, following the arrival of federal agents early that month. Medics experienced and witnessed indiscriminate attacks, both by the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) and by federal officers. In some cases, medics reported that these attacks appeared to be targeting medics. A number of medics sustained serious injuries while providing medical assistance to protestors due to the use of force by PPB and federal agents. Except for rare reported instances, there was a lack of official medical assistance at the protests, which prompted volunteer medics to organize to provide assistance for injured demonstrators. There were also two reported incidents of law enforcement destruction of medical supplies.

A. Medics reported increasing number of serious injuries among protestors from kinetic impact projectiles after engagement by federal forces

The types of injuries resulting from law enforcement use of force that medics reported treating included: eye and skin irritation from tear gas and pepper spray; burns from flash grenades; abrasions; avulsions; contusions; sprains; lacerated scalps, necks, hands, and feet; bone fractures; trauma-induced seizures; and traumatic brain injuries.

Several medics described their perceptions that the number and severity of injuries they were treating had increased since early July, when federal agents had joined the PPB, with more patients requiring transport to emergency departments. Interviewees noted a dramatic increase in head injuries. One coordinator of the OHSU4BLM medic group, Michelle Ozaki,[36] reported that, earlier in the protests, medics transported people to the emergency department only once or twice a week, usually with head injuries or concussions.

She described how this had changed after the arrival of federal officers:

“In the last two weeks, on Saturday alone, three people we treated had injuries serious enough to be taken to an emergency department. The federal officials and local police do not seem to be wanting to disperse protestors anymore, they seem to be wanting to hurt protestors. We are now seeing more head injuries. They are throwing flash bangs and tear gas canisters at head level, whereas before they would roll the canisters on the ground. Last Saturday [July 25], I was at 4th and Main and my feet were surrounded by tear gas canisters. The ground was littered with canisters…. Yes, now they seem to just want to hurt us.”

“Nat Griffin,”[37] a former emergency medical technician (EMT) and current nursing student, also described an increase in injuries. Griffin regularly drove and staffed the “Medical Utility Vehicle” (MUV), a decommissioned ambulance used by the volunteer medics to provide support for the injured:

“For the past week or two, we are calling an ambulance at least once – sometimes three times – a night. One night, we had to transport three people to the ED [emergency department] because either the ambulance didn’t come, the ambulance was not where [the 911 dispatcher] said it would be, and in one case, the person asked us to take them instead. I have treated more impact wounds since the [federal agents] came.… There has been an enormous uptake of 303 rounds … made of hard glass and plastic that will hit and shatter on impact. These [often cause] deep lacerations … [in] strategic places, usually right where the body armor just finishes. Usually just one round to the throat, jaw, and head.”

“Izzy Landis,”[38] a former EMT and medic who owns and manages the MUV, described more extreme and intentional violence, particularly from the federal agents:

“We started seeing baton wounds, trauma to the hand. Usually, PPB did not get close enough to hit people with batons…. This was new. Federal agents would race after an individual who was not necessarily doing anything … grab him, turn him over on his back, tear his mask off, and spray mace in his face. I saw this happen… from about 20 to 30 yards. I saw lots of baton injuries, shoving people out of the way, wrist, hand, and head injuries. They shoot [impact munitions] from the top floors, also.

“Just in the last two to three weeks, I have treated three major avulsions, medium or full-thickness wounds with chunks of skin missing. The most concerning was a full-thickness wound/avulsion on a woman’s left neck under her chin. [See photo #2.] That was from Friday morning, July 24 … just after midnight. She was standing around in Chapman Park, not doing anything…. As we were treating her, we could hear gargling through the wound. It was right near her trachea and carotid [artery]. I could see her jaw [bone] through the wound.”

“Federal agents would race after an individual who was not necessarily doing anything … grab him, turn him over on his back, tear his mask off, and spray mace in his face.”

“Izzy Landis,” former EMT and volunteer medic.

Photo: Volunteer medic Izzy Landis treated this woman, who was shot under her chin during the protests on July 24. “We could hear gargling through the wound… It was right near her trachea and carotid… I could see her jaw [bone] through the wound,” Landis told PHR.

Nate Cohen,[39] a former EMT and volunteer medic, noted that he had treated the highest number of clinically significant injuries in the last four nights he worked as a medic at the protests [July 23-25, July 29] than he had treated in more than 100 protests over the years at which he had worked as a medic. He described treating multiple minor pepper ball injuries that left welts about the size of a nickel or a quarter. He treated a severe two-inch deep laceration on a protestor’s lateral patella from an impact round or canister. He treated two other people who had been injured by tear gas canisters, one breaking a protestor’s hand. He described only seeing federal officials the nights he was out; he did not see officials dressed as PPB officers.

“The violence the feds are doing is the worst I have ever seen. It is a higher level of aggression, which is saying something compared to PPB. They are using weapons much more indiscriminately, directly hitting people with canisters, shooting canisters directly at people. The angle launch of canisters is much lower with the feds. With PPB, they are still launching into the crowd, but they are shooting high, so they arc – though still can hit people when they fall. What we have noticed is feds shoot at head-level in a straight line. People have to dive to get out of the way. One friend was shot directly in the abdomen with a tear gas canister. Four to five friends have been badly injured. Many more head injuries from being shot directly in the head. The feds don’t seem to have training in how to use these weapons in the way they are designed.”

“Bill Daniele,”[40] a former Army combat medic and volunteer at the protests, told PHR that he perceived an increased level of force since the arrival of federal agents in July: “I do feel that they seem to be more aggressively injuring medics. It is definitely true that if you break the medical support demonstrators receive, then you break the crowd.”

In a July 30 interview with PHR, Deputy Fire Chief Steve Bregman, who oversees Rapid Response Team (RRT) medics embedded with the local police, also stated his belief that, when the federal agents arrived, there was an “uptick” in injuries of protestors.

“I do feel that they seem to be more aggressively injuring medics. It is definitely true that if you break the medical support demonstrators receive, then you break the crowd.”

Bill Daniele, former Army medic and volunteer medic

PHR’s investigation team attended and observed the federal courthouse protests on July 24-25. To gain a snapshot of injured protestors who were treated by medics, we interviewed several protestors who were injured by law enforcement use of force that weekend.

1. Akitora Ishii,[41] volunteer helping serve food – impact munitions injury to the eye

Akitora Ishii, a recent college graduate, was helping serve food with Riot Ribs in Lownsdale Square early on July 26, when an impact munition launched by federal officials hit him in the eye.

“I [served hot dogs] until they [the officers] stormed the park again, somewhere from 3:15 to 3:45 a.m. I didn’t really see a lot of what led to the rush … but then I heard explosions go off and saw people running, moving out of the park. I took cover by the grills after the explosion. I tried to look around and see what was going on.

There were a few [shields on the ground] about seven feet away. I popped up to see which way to run and then I got hit. I was wearing goggles when I was hit. Very soon after, I was stuck in a cloud of tear gas. I called out for help … and only called out twice before someone was at my side. He held my shoulders and guided me to the rest of his street medic team. I knew I got hit pretty bad but could hear people reacting: ‘Oh my God, there is so much blood!’ The medics concluded ‘We need to not touch this at all until he gets to the ER.’ It was a shock to go from handing out hot dogs to hungry people to being shot in the face.”

In the emergency department (ED), physicians tried to flush out the debris from Ishii’s eye, which was difficult due to the swelling, and stitch the lacerations. He noted that the ED doctor described seeing fine metallic powder on his face and in the wounds and his eye. Later that day, he required general anesthesia for ophthalmologists to fully clean out his eye.

“It was a shock to go from handing out hot dogs to hungry people to being shot in the face.”

Akitora Ishii, volunteer food server.

Two weeks after the injury, Ishii described the pain as better but still present. He had 80-90 percent of his vision back in the mornings, but by the end of each day, that declined to 10-20 percent of vision. There was still blood in his eye (hyphema), but doctors were hopeful that his pre-incident vision will return.

2. Kristen Jessie-Uyanik,[42] participant in “Wall of Moms” – head injury from KIP

Kristen Jessie-Uyanik is a 41-year-old information technology consultant and mother of three, who began to attend protests at the Justice Center when the “Wall of Moms” formed. She participated several nights from Sunday, July 19 until Saturday, July 25. Jessie-Uyanik described the events leading to her being shot by a projectile directly in her forehead by federal officials as she stood with her arms linked with other moms on July 25:

“We marched in as a group to the Justice Center after 10 p.m…. There was an enormous crowd. I was 10 feet away from the fence [separating the federal officials and protestors] … in the first row…. The feds came out of the building at about 10:45 p.m. and just stood there…. Nobody was trying to take the fence apart…. I put my goggles back on and stood there, observing the scene. The people in my vicinity were just standing there.

Between 10:53 and 11 p.m., I heard a boom and felt something hit my forehead very hard and knock me back while I was linking arms with other moms. I slumped and wondered what had happened. I did not feel pain. I felt my forehead and felt nothing at first. Then, I felt the warmth and the blood. I realized I was not fine. I screamed, ‘My eyes!,’ according to somebody near me. It was right between my eyes. I was slumped down and being held by people on either side. My cousin told me to take off my helmet…. There was a lot of blood on my helmet. A tall person picked me up and I felt that I was hoisted above other people. He started to yell, ‘Medic!’ and run with me west from Third to Fourth.”

Medics transported Jessie-Uyanik to the MUV, which drove her to the intersection several blocks away, where the 911 dispatcher said the ambulance would be. After waiting “what seemed like a long time,” the MUV drove her to a hospital emergency department. There, a CT scan did not find observable brain injury, bleeding, or skull fractures. Doctors stitched the forehead laceration.

At the time of PHR’s interview with Jessie-Uyanik on July 26 – less than 24 hours after the incident – she had a vertical 4- x 2-cm-deep laceration on her lower forehead between her eyebrows closed with seven stitches, consistent with an injury from a sharp projectile. She continued to have severe pain at the site, headache, and nausea.

“I heard a boom and felt something hit my forehead very hard and knock me back while I was linking arms with other moms…. I felt my forehead and … felt the warmth and the blood…. It was right between my eyes.”

Kristen Jessie-Uyanik, protestor shot in the head with a projectile

The PHR team spoke with two other “Wall of Moms” participants who were standing directly behind Jessie-Uyanik, in the second row of women. They both confirmed her account. Kelly Campbell[43] posted an account on Facebook[44] and described the events to PHR by phone:

“It was about 10:50 p.m., we heard a sound like ‘pew, pew, pew,’ and she [Jessie-Uyanik] moaned and stumbled backwards. There had been no provocation. We were all just standing there. Suddenly they burst out – it seems to happen suddenly at shift changes…. My friends and I helped carry her back to a medic and her goggles fell on the ground and were full of blood. Some of her blood was on my arm. We then noticed that the filter on the side of the mask of my friend standing next to me had a big gouge out of it, presumably from whatever was fired. This happened with no warning, no provocation, no order to disperse … and before tear gas was deployed. A federal officer shot a nonviolent protestor in the face, from maybe 25 feet away. I knew these kinds of things were happening but to witness it first-hand and up close was a shock.”

The PHR team also spoke with the woman standing next to Campbell, a single mother of two who did not want to be identified.[45] She described what happened:

“I was behind Kristen. I was staring up at the [federal] officials behind the fence…. She was standing there completely quiet, just standing there…. I said, ‘Are you okay?’ She said, ‘No. I was shot in the head.’…. I yelled for a medic, who are usually in the back. She was starting to lose consciousness, she was bleeding profusely…. Finally [a medic] came up and grabbed her in a fire fighter hold, slung her over his shoulder, and sprinted away with her. I was covered with her blood on my right forearm to my hand…. My friend noticed that my filter was ripped from the shrapnel or whatever it was. The filter had protected my face. It would have ripped into my face if I had not been wearing the filter…. That evening, nobody had even started any provocations. Nobody had thrown fireworks or tried to disassemble the fence.”

3. Ellen Urbani,[46] participant in the “Wall of Moms” – foot injured by projectile

Ellen Urbani is a 50-year-old author and mother of two who joined the “Wall of Moms” the third day after it formed on July 18. She described the events on July 24, when she was shot in her left foot with a projectile by federal officials while she was standing peacefully with arms linked with other moms. The projectile broke her big toe, “as if you split the bone with a hatchet.”

Urbani stated that she had initially hesitated to join the protest because she has severe asthma and had broken her right ankle two weeks earlier and was still on crutches. The arrival of federal officials, however, convinced her to join the “Wall of Moms.” Wearing a N100 respirator, swim goggles, and a snowboard helmet, she participated in the protests from July 22 to July 24.

On the night of Friday, July 24, Urbani wore an immobilization cast on her right leg but did not bring her crutches. As she did on prior nights, she linked arms with other moms in front of the Justice Center. At about 10:45 p.m., a protest coordinator instructed them to put their gear on, so she put her respirator and helmet on. She described suddenly being enveloped with tear gas:

“I could smell it but because of the respirator I could breathe. People were collapsing to the ground choking and coughing, one person vomited, people were stumbling…. We were at the corner of the federal courthouse. I realized I was being pulled to the front line, but since I could breathe, I felt it was fine…. I personally did not witness any provocation, violence or illegal behavior from the crowd…. I am standing with a group of peaceful people exercising their rights and not doing anything wrong….

[The federal officials] kept throwing tear gas…. We all had arms linked…. The federal officials were shooting flash bang grenades. The noise was concussive, the whole line would shudder…. We were enveloped with tear gas. You could not see anything. My head kept getting hit with hard projectiles that made me feel I was being shot with automatic fire. I had my helmet on. It really hurt…. I kept thinking that I couldn’t believe how relentless they were.

What I perceived next was that the gas lifted…. I realized I was right in front of the courthouse…. Everybody in front of us was gone. I thought, ‘Oh shit. We are the front line. We are defenseless on the front line.’ We were assaulted with gas, pepper balls…. Then I knew that they were there to hurt us. Everybody had retreated and there were five moms with arms linked standing in the street.

“My head kept getting hit with hard projectiles that made me feel I was being shot with automatic fire…. I kept thinking that I couldn’t believe how relentless they were…. We were assaulted with gas, pepper balls…. Then I knew that they were there to hurt us.”

Ellen Urbani, protestor shot in the foot

That was the moment I got shot. I suddenly felt a smashing pain on my left foot. The pain was overwhelming. I thought, ‘They shot me!’ I was so surprised. Then, I thought, ‘Oh my God. They broke my good foot.’ My friend bent over and was also hit in the foot. It felt like somebody had taken a sledgehammer and swung it as hard as possible on the front of my foot. I stayed on my feet, and she went down…. We were at most 10 feet [away from the officers]. We realized they were shooting us at pointblank range.”

Urbani described to us how medics helped remove her and her friend to an open space, examined her foot, and took her to the hospital. At the emergency department, X-rays showed a vertical fracture through the metatarsal bone of her big toe. At the time of our interview, Urbani was using a wheelchair to avoid putting weight on that foot.

4. “Jason Nozak,”[47] a nurse who joined a health professional march – thigh injured by a projectile

Jason Nozak, a registered nurse, described joining the health professional group marching in front of the Justice Center and federal courthouse on the evening of July 24. He and his partner, also a nurse, dressed in their nurse scrubs, bike helmets, and half-face respirators with P100 particulate filters. He carried a shield (plastic rain barrel, three feet tall) stenciled with the caduceus (the medical symbol of intertwined snakes) and “RN, registered nurse” in text to indicate “we are medical professionals, we are nurses, protesting.” He described how, at about 11 p.m., federal agents began shooting pepper balls and impact rounds from air-powered rifles and launching tear gas canisters.

Nozak described suddenly feeling as if somebody had taken a baseball bat and “whacked” him in the thigh. He found it difficult to walk but was not completely disabled. He described the impact site where the skin was damaged to be about the size of a nickel, and a surrounding circular area of bruising about the size of his hand. [See Photo #9.) He noted that if the federal officials had hit his knee, the impact seemed hard enough to possibly have shattered the patella.

Bryan Wolf, MD is a 37-year-old diagnostic radiologist and faculty member at Oregon health & Science University (OHSU) who served as the faculty liaison for the OSHU4BLM volunteer medical response group. As he saw the safety risks the student volunteers faced from projectiles and tear gas, Dr. Wolf helped raise funds to buy them safety equipment, including gas masks, goggles, and helmets. An activist later donated bullet-proof vests.

On July 2, Dr. Wolf wrote OHSU leadership, resigning as a faculty volunteer due to concerns about the safety risks the students were facing from law enforcement use of force. He then devoted himself to efforts to de-escalate tensions and violence. He dressed in his white lab coat and carried a sign that read “DE-ESCALATE” superimposed on a large red cross, often positioning himself between protestors and law enforcement officials and begging police to put their barrels down and not to shoot. In interviews with PHR, Dr. Wolf described multiple incidents in which he was shot by projectiles; he described the incidents from June 10 to July 4 in formal testimony to the Oregon state legislature. He told PHR he felt so traumatized that he did not go to the protests between July 4 and July 18. On July 19, while he was standing in his white coat holding his sign, federal agents shot Dr. Wolf directly with impact munitions. Since July 19, he continues to provide radiologic diagnostic care at OHSU, where he has reviewed a number of cases of head and neck wounds from KIPs fired by federal officers.

On our targeted medical exam on July 25, Dr. Wolf had several significant lesions from July 19 that were consistent with projectile injuries: a 2-cm abrasion shaped like a crescent one inch above his right Iliac Crest surrounded by a 10- x 2-cm eccymosis, and a 2- x 1-cm. abrasion surrounded by a 11- x 4-cm eccymosis on his left medial calf 11 cm proximal to his ankle. He reported moderate to severe PTSD symptoms on the abbreviated PCL-C scale.

B. Volunteer medics both witnessed and experienced indiscriminate attacks, including attacks apparently targeting medics

1. Massive use of tear gas:

Both PPB and federal officials employed massive amounts of chemical irritants against demonstrators, including pepper spray and balls, and CS tear gas. PHR and other medical groups have documented the potential adverse health effects from these weapons, and current research is ongoing on the effects of such large quantities deployed in the Portland protests.[48] Since this investigation took place, on September 10, 2020, the mayor of Portland, who is also the Portland police commissioner, issued a directive ending the use of CS gas for crowd control in Portland.[49]

All interviewees who attended the Portland demonstrations were exposed to some form of chemical irritant and described the resulting severe pain, disorientation, and discomfort.

2. Medics reported being targeted by projectiles

Several medics PHR spoke to described what they believed were targeted attacks on medics by law enforcement officers firing projectiles.

Izzy Landis, the medic who managed the MUV, described how she was burned by a flash grenade while attending to an injured protestor at the Justice Center in early June:

“It was broad daylight after the 8 p.m. curfew. The [PPB] were driving around in militarized vehicles, wearing riot gear. My patient … had fallen while running with the crowd [from the Justice Center], hit his head, and had a 1-inch superficial laceration. I was stopping the bleed and applying disinfectant…. I was bent over caring for the patient…. I had a red backpack with a huge ‘Street Medic First Aid’ patch, red crosses on arms, on my hat. They [police] were … throwing flash grenades and tear gas at people. There was a group of people 30 feet away from me, and I was apart from them with the patient. Rather than throwing at the large crowd, police threw a flash grenade at my heel. I had a burn where my pants ended and boot began. It felt like the worst sun burn I ever had. It was maybe a second-degree burn.”

Landis believes that both the local and federal officials were targeting medics. She said she is always clearly marked as a medic; nonetheless, she said, “There have been days that I have been trying to walk to treat a patient and suddenly there is tear gas and flash grenades right in front of me.”

Chris Wise,[50] a former EMT and volunteer medic at the protests, suffered numerous injuries at the hands of law enforcement, three of them serious, and noted his concern about whether on occasion he was deliberately targeted:

“It is hard not to feel that they are at times deliberately shooting at me. One time I was shot with pepper balls three times, right in the middle of a group of people. They were aiming … [with] the [type of] munitions [where] you pick a target and shoot that target. Each of these times, they chose to shoot at me and not at somebody else. Tear gas is one thing. Being hit by a tear canister is another…. The tear gas canister that hit me in the head – somebody had to aim that. It was thrown by about 100 feet and must have [been] aimed at me.”

Wise described another example when he believed he was targeted by a PPB officer. On June 28, dressed as a medic, Wise witnessed an officer at close range spray a protestor’s eyes with bear mace. He rushed to the protestor to pull her out of harm’s way and flush her eyes with water. When he reached the protestor, the officer turned to him and sprayed him directly in the eyes at a distance of approximately 6 inches. His eyes burned and he was unable to see, so others helped him seek shelter and flushed his eyes for 45 minutes.

“It is hard not to feel that they are at times deliberately shooting at me. One time I was shot with pepper balls three times…. Each of these times they chose to shoot at me and not at somebody else…. The tear gas canister that hit me in the head – somebody had to aim that.”

Chris Wise, former EMT and volunteer medic

Dr. Anita Randolph,[51] a neuroscience post-doctoral researcher who helped organize the OHSU4BLM medic group, has regularly volunteered as a medic at the protests and has investigated the health effects of tear gas.[52] She described incidents when it seemed law enforcement had targeted medics at the protests:

“All medics are very clearly marked. Red crosses are all over. Usually groups of medics are at the perimeter of where there is a crowd of demonstrators, watching from the back lines until about 10-11 p.m. Then, they put on their helmets and go into the crowd to see if anybody needs help. I don’t think the shooting of medics is always indiscriminate. Sometimes you see police point at a medic clearly marked with red crosses and then that person is shot with a rubber bullet. I have seen that. They shoot and then pat each other on the back.”

Nearly all medics PHR interviewed continued to wear clearly marked insignia, despite some believing that medic insignia led them to being targeted by police. “Joan Garcia,”[53] the one medic who reported not wearing insignia at the protests, said, “I feel that I would be targeted if I wore a red cross. I feel that they are targeting people with red crosses and journalists first, any sort of press or legal observers from the ACLU…. I know one medic who has been hit with different projectiles 11 times, all while clearly being marked with a red cross.”

All medics we interviewed emphasized that they share a code of ethics that their role when working as medics is not to join the protests but to provide medical assistance to all who need it. We asked each person we interviewed if they had ever heard reports of or witnessed anyone marked as a medic with red crosses and/or other medic insignia engaging in violent behaviors. Unanimously, the answer was: “No.” As a coordinator of OHSU4BLM stated, “In all our nights out, we have never seen anyone wearing a red cross engaging in any act of violence.”

“Sometimes you see police point at a medic clearly marked with red crosses and then that person is shot with a rubber bullet. I have seen that. They shoot and then pat each other on the back.”

Dr. Anita Randolph, neuroscience post-doctoral researcher and volunteer medic

C. Medics sustained serious injuries by PPB and federal agents while providing medical assistance to protestors

1. Christopher Wise,[54] volunteer medic – injured by rubber bullets

Christopher Wise is one of several Black medics and a former EMT who has rendered medical aid at the Portland protests most nights since May 29. When he works as a medic, he always wears a denim jacket with red crosses on both shoulders, a red cross over his left breast pocket, and “Medic” spelled in large block letters. Wise described suffering multiple minor injuries and three clinically significant injuries from law enforcement use of force.

On June 2, a Portland police officer shot Wise in the shin with a rubber bullet. During a tear gas attack, Wise pulled a fallen protestor out of the cloud of tear gas, moved him to a bench, and began to examine his minor injuries. While he was bent over the protestor, he felt a sharp pain in his leg: “I looked down and there was no hole in the pant, but under the pant leg there was an almost complete avulsion [skin was completely torn off].” He washed the wound and continued to attend to his patient. About a week later, a physician looked at the wound and said it was infected. Wise was prescribed a course of antibiotics. Nearly two months later, upon PHR’s examination of Wise, the wound had still not completely closed.

“As one of the few Black medics, I think it is really important that I am out there treating people. They are trying to intimidate us. If there aren’t medics, people will be afraid to come out. There won’t be anybody to treat them if they get injured. I have to be there.”

Christopher Wise, volunteer medic

On July 4, after the Portland police declared the demonstration a “riot” and fired tear gas, the police formed a riot line and began pushing protestors away from the Justice Center to the north. Wise described walking backward facing the police to monitor for potential injuries. “We were backing up, and the officer yelled, ‘Move!’ and, rushing by several protestors, tackled me to the ground. I fell to the ground straight backwards and put my arms back to brace myself. I sprained my left shoulder. I landed on my palm and had a severe avulsion about the size of a quarter.”

On July 21, Wise was working as a medic, standing just behind the first row of protestors between the federal courthouse and the Justice Center. A group of federal officers were standing at the intersection of Main and 3rd Streets. Protestors in the first row were kneeling and holding wooden shields to block projectiles. Chris was standing and, at 6 feet 5 inches, he was taller than many around him. He described what happened:

“I saw a little light coming toward me like a firecracker. I turned my head and crouched a little bit. It hit my right temple. If I had not moved it would have hit me … in the eye. I immediately had tinnitus, ringing in my ears. I took one hand and put pressure on the wound. I knelt on one knee until the tinnitus went away. They said they had to get me to the ED right away. I kept providing medical care … mainly eye washes and treating abrasions…. I felt tired … was nauseous, slight worsening of balance. I was having trouble ordering my thoughts.”

Photo: Andrew Stanbridge for Physicians for Human Rights

Later that day, Wise went to the Providence St. Vincent Medical Center Emergency Department. With his authorization, PHR secured his medical records from that visit. The records described his diagnoses as a concussion, with severe bruising and an abrasion-laceration of the right temple. (See photo #11) PHR conducted a medical examination of Wise on July 29, which showed resolving wounds consistent with his description of his injuries from June 2, July 4, and July 21.[55]

In light of the attacks on him, PHR asked Wise why he continued to go to the protests to work as a medic. He replied, “As one of the few Black medics, I think it is really important that I am out there treating people. They are trying to intimidate us. If there aren’t medics, people will be afraid to come out. There won’t be anybody to treat them if they get injured. I have to be there.”

2. Nate Cohen,[56] volunteer medic at protests – injured by a tear gas canister

Nate Cohen is a graduate student and former EMT who has been involved in racial justice advocacy since 2016, working closely with the group Don’t Shoot Portland. He estimates he has worked as a medic at about 100 protests. He did not experience significant injuries from law enforcement at the Portland protests until July 25, when he was shot in the chest with a tear gas canister at a range of 20 feet. That night, he wore multiple insignia marking his status as a medic.

Cohen described the events leading to his injury at about 1 a.m.:

“They were lobbing tear gas and shooting pepper balls. I was aware that I seemed to be the only medic there. I was running around giving people eye washes, helped somebody who had fallen…. I checked on people who were hunched over to check they were okay. I was working my way back and forth across the front line of protestors….

One official pointed at me and spoke to another. I then ran across the street to see if they would keep looking at me, and they did. I saw a part of a triple canister land behind a group of journalists and legal observers who were clearly marked standing on the northeast corner of 3rd and Salmon. I saw the canister land and spew gas. I ran up and doused it with a water bottle to extinguish it. I was hunched down over it. I checked on a person next to it who was hunched over a lamp post, checked on a journalist who was leaning against a car taking photos over the hood of a car…. The car was between me and the feds. They were less than 20 feet away. I straightened up after checking on the journalist.

When I stood up straight and looked towards the feds, I felt something slam into my chest that almost made me lose my balance. The impact pushed me back a few steps. I looked down and saw a burning canister spewing gas at my feet. I was in so much pain, I don’t remember anything else.”

Cohen noted that a photojournalist friend had been livestreaming and captured audio at the time when he was hit. He recalled somebody yelling “The feds just shot a medic in the chest.” He was taken in a private car to a local emergency department. X-rays there did not show any fractures, and an EKG showed that the impact had not induced any arrythmias. This was of concern, as Cohen has a rare variant of Wolff Parkinson White syndrome that predisposes to potentially fatal arrythmias. Cohen was diagnosed with a chest wall contusion with an abrasion but no lacerations or avulsions.

“When I stood up straight and looked towards the feds, I felt something slam into my chest that almost made me lose my balance. The impact pushed me back a few steps. I looked down and saw a burning canister spewing gas at my feet. I was in so much pain, I don’t remember anything else.”

Nate Cohen, former EMT and volunteer medic

At the time of PHR’s interview five days later, Cohen described continuing to feel significant pain over the site. On physical exam, he had a 15- x 12-cm hematoma over his left breast, extending over the nipple, with a 4-cm full abrasion where the canister hit, creating an almost full circle outlining the size of the canister (a 5.5- cm diameter canister). He scored as having moderate PTSD symptoms on the abbreviated PCL-C.

3. Bill Daniele, volunteer medic at protests – injured by tear gas canister and rubber bullet

Bill Daniele is a former Army combat medic who has worked as a volunteer medic at the Portland protests most nights since the killing of George Floyd.

Bill described that, until July, he had never witnessed tear gas canisters being shot directly at protestors. By late July, he had treated several protestors with injuries from tear gas canisters. Then, on July 18, he was shot himself:

“I was working as a medic. I was clearly marked … bright pink crosses … on a white helmet, ‘Medic’ in black sharpie on my backpack, and crosses on both shoulders. I was coming from the back of the Justice Center. Somebody standing near the front line was calling for a respirator, so I was heading toward them to see if they were okay. I saw that one of the Border Patrol officials was looking right at me and tracking me…. He was standing about 10-20 feet from me on the street corner with some other [agents]…. He pointed me out to the guy holding the grenade launcher. I was holding my hands up in the surrender position over my head saying as loud as I could, ‘I am a medic checking injuries. Don’t shoot.’ But the guy pointed the grenade launcher and shot me with a 40-mm CS canister that hit my left thigh…. I turned in pain … and they hit me with a rubber bullet on my right lateral thigh.”

Bill said he still felt considerable pain from these injuries but was continuing to work as a medic. On physical exam by PHR, he had a large resolving hematoma/ecchymosis on his left thigh approximately 14 x 10 cm, with no abrasions/excoriations evident. His right thigh had an approximately 4- x 4-cm resolving ecchymosis with an erythematous abrasion in middle. He has been diagnosed with PTSD since his military service, so we did not administer the PCL-C PTSD scale.

“I was working as a medic. I was clearly marked…. I was holding my hands up in the surrender position over my head saying as loud as I could, ‘I am a medic checking injuries. Don’t shoot.’ But the guy pointed the grenade launcher and shot me with a 40-mm CS canister that hit my left thigh…. I turned in pain … and they hit me with a rubber bullet on my right lateral thigh.”

Bill Daniele, former Army medic and volunteer medic

4. “Michael Blake,”[57] frontline volunteer medic – injured by a projectile

Michael Blake is an EMT who has worked as a frontline volunteer medic three to four times a week since the second day of the protests in late May. He always wears large orange crosses on his helmet, arms, and backpack, despite his belief that wearing medical insignia makes him more of a target for the police.

Blake described a number of incidents in which he suffered minor injuries from flash bangs or projectiles. He described two occasions (June 11, June 30) in which he was hit with batons by PPB officers while he was clearly identified as a medic but suffered “only bruises.”

Blake’s most serious injury occurred on June 2, when a PPB officer about 80-100 feet behind him shot him in the back of his thigh with a projectile.

“There was a small group of PPB officers behind the fence at the Justice Center and there was a small group of protestors in front of the fence at about 9:30-10:00 p.m…. Nobody was being violent…. All at once, the police started firing tear gas and flash bangs. Everybody was screaming. Five individuals were unable to move – one was a young man with a walker, three of them were on all fours wheezing, coughing, vomiting, and one was a teenage girl having a panic attack. She was wheezing, crying, yelling for her mom, saying she was going to die. They kept firing tear gas and flash bangs. Six people were lying on the ground. The PPB left and did not arrest any of us. It was maybe 2-3 minutes but that is a long time when you can’t breathe.

“Later, … I was 80-100 feet ahead of [PPB officers] with my hands up, crosses on my back, and they shot me right in the back of my left thigh. It was a 7 out of 10 pain. It made me drop to my knees…. It still hurts two months later.”

“All at once, the police started firing tear gas and flash bangs. Everybody was screaming. Five individuals were unable to move – one was a young man with a walker, three of them were on all fours wheezing, coughing, vomiting, and one was a teenage girl having a panic attack. She was wheezing, crying, yelling for her mom, saying she was going to die.”

Michael Blake, EMT and volunteer medic

As this was a phone interview, PHR did not conduct a medical examination. On the abbreviated PCL-C, Blake scored as having severe PTSD symptoms.

D. Due to a lack of official medical assistance, volunteer medics had to organize to provide help for injured demonstrators

All of the people PHR interviewed stated that, except for a few instances, they did not witness official EMTs or paramedics associated with the PPB or Portland or Multnomah County Fire Departments provide medical assistance to protestors at the demonstration sites in Portland. Several interviewees noted that there was a period of about two weeks in June when a group of paramedics from the Portland Fire Department provided medical assistance at demonstrations that occurred in East Portland, but they were then withdrawn and did not appear again. Deputy Fire Chief Steve Bregman confirmed to PHR that, for two weeks in June, paramedics from the Fire Department worked as a special First Aid team at the events in East Portland. He noted that, due to the peaceful nature of those events, the teams did not have many patient encounters. As the number of marches dwindled by the end of June, the Fire Department decided there was less need for a special team and that emergencies could be handled by 911, so the team was re-assigned. He also said that there are 12-15 RRT medics present, who have special emergency and trauma training and are equipped with body armor and ballistic helmets.

Beginning June 11, students, employees, and faculty from OHSU, as OHSU4BLM, maintained a medical supply and assistance post in Chapman Square from approximately 7 p.m. to 11 p.m. nightly. By June 23, several volunteers with medical supplies remained after the post was packed up to continue providing medical assistance. Over the two months that OHSU volunteers worked as medics at the protests, they noted only one incident when a paramedic affiliated with the PPB aided an injured demonstrator. Student coordinator Michelle Ozaki described that incident:

“I treated one of the first patients who really needed an ambulance. It was June 26, about 11:30 p.m. There was a patient hit with a flash bang that exploded on the back of his head. He had a laceration on the back of his head that was bleeding profusely. We called an ambulance immediately. I was applying pressure, trying to find out his name. was out of it. He could barely respond. He passed out within a few minutes.