“No Place Is Safe for Health Care”: The Attack on Syria’s al-Atareb Hospital is a Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) Case Study

Overview

On March 21, 2021, three artillery strikes hit al-Atareb hospital in the western countryside of Aleppo governorate. The missiles directly hit the hospital’s entrance and destroyed the orthopedic clinic that was in operation during the attack. Seven patients were killed, and 15 people were injured, including five medical staff. As a result of the attack, the hospital suspended all services for two weeks.

This latest attack on a health facility is part of an extensive record of violence against health care during the Syrian conflict. Since the conflict began in March 2011, parties to the fighting have carried out indiscriminate attacks on or direct targeting of health care facilities across the country. Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) has documented attacks on medical facilities and personnel in Syria throughout the 10-year conflict and has verified 600 attacks on medical facilities.[1] Syrian government forces and their allies have perpetrated 90 percent of the attacks, with 541 attacks attributable to the Syrian army and/or Russian forces. These attacks have effectively transformed medical facilities into deadly spaces, both for health care workers and their patients, and decimated the health sector throughout the country. This is the first in a series of brief case studies that describe in detail attacks on health care facilities and the health impacts on the communities they serve. As discussed in the legal framework section below, the attacks appear to violate multiple international laws, including international humanitarian law, international criminal law, and the right to health.

Methods

This case study, a collaboration between PHR and the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), relies on a number of data sources, including desk research, internal documents of the organizations operating al-Atareb hospital, and interviews with five health care workers present during the March 2021 attack. Significantly, among the interviewees, three are also residents of al-Atareb town, including an orthopedic surgeon who lost the use of one eye in the attack, and two technicians. All interviews were conducted remotely by a bilingual researcher using the WhatsApp platform between April 15 and May 18, 2021, and informed consent was obtained.

Al-Atareb Surgical Hospital Location and Background

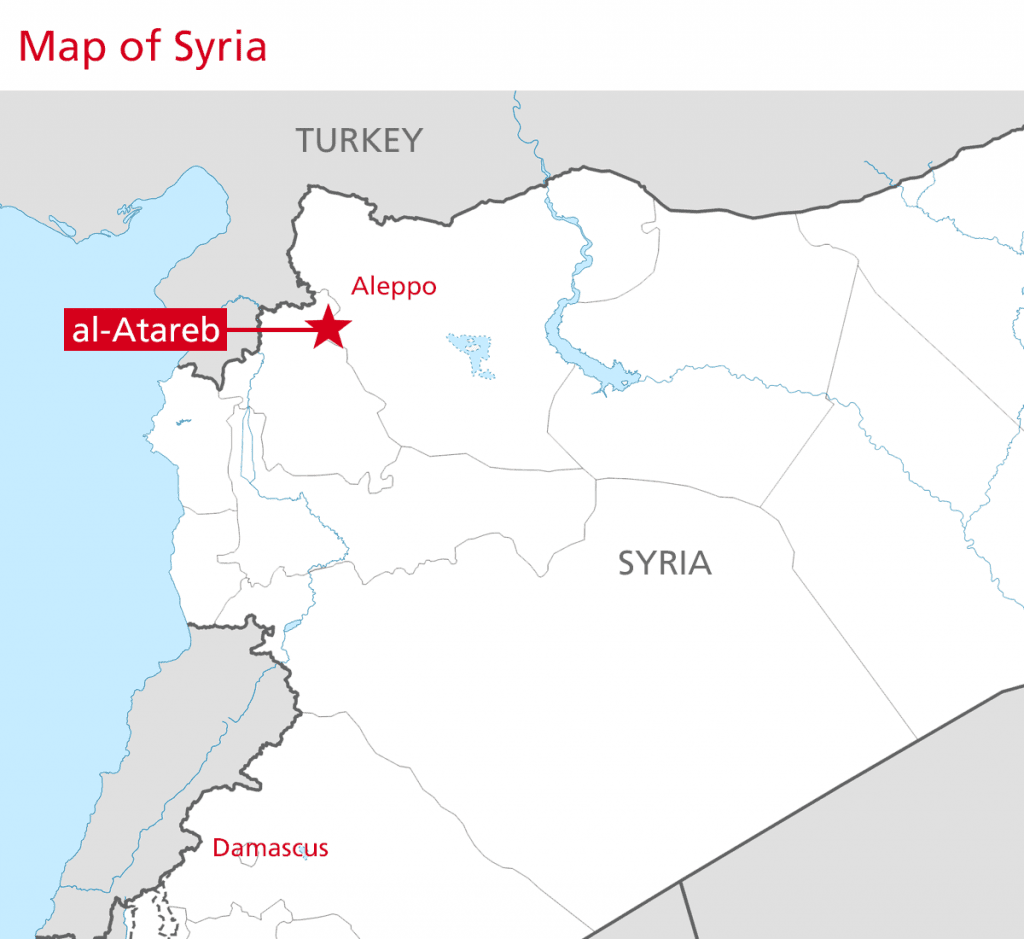

The town of al-Atareb is an important commercial center located on the main road that connects the Aleppo governorate with Idlib and the western countryside of Aleppo. It is strategically located 15 miles (25 kilometers) west of Aleppo city, the second largest city in Syria, and 15 miles (25 kilometers) southeast of the Turkish border.

The original “old” al-Atareb hospital was established in late 2012 by two Syrian NGOs (Hand in Hand for Aid and Orient Humanitarian). The facility included two operating rooms and eight outpatient clinics, including for reproductive health; pediatrics; ophthalmology; orthopedics; neurology; urology; ear, nose, and throat; and internal medicine. The caseload in 2013 was 6,000 patients a month.[2]

By March 2021, the al-Atareb health care system, now supported by SAMS, was comprised of two separate facilities and a vaccination clinic, and served a regional population of 182,358 people, 40.4 percent of whom are internally displaced persons (IDPs). By early 2021, the population al-Atareb city was 22,220, nearly double the pre-conflict census.[3] Almost 50 percent (11,208) of the town’s population is internally displaced.[4] Because al-Atareb is close to the line of fighting, it is affordable for those internally displaced people with few resources.

As the conflict progressed, the al-Atareb hospital system became increasingly important for the region. This was particularly the case in 2016, after the Syrian government’s offensive in Aleppo city, which deliberately targeted health facilities and displaced the population. Unable to access health care services in Aleppo city, people in the surrounding villages sought health services in al-Atareb. Service provision in al-Atareb expanded enough that people have traveled from northern Hama governorate, a distance of approximately 60 miles (100 kilometers), to al-Atareb to seek medical care.

A Pattern of Attacks on Health Facilities

Since 2015, the al-Atareb health system has been subjected to multiple airstrikes. SAMS, which uses a different but complementary methodology to PHR’s, documented at least six airstrikes on the “old” al-Atareb hospital between June 2015 and November 2016. The repeated attacks forced the hospital administration to relocate to a subterranean facility, constructed in 2017 by SAMS, in an attempt to provide protection for its staff and patients.

| Facility Type at Time of the Attack | Date of Attack | Weapon Used | Perpetrator Attribution[5] |

| Health Center | June 4, 2015 | Barrel Bomb | Syrian Government Forces |

| Field Hospital | July 23, 2016 | Aerial Bombardment | Syrian Government or Russian Forces |

| Field Hospital | November 14, 2016 | Aerial Bombardment | Syrian Government or Russian Forces |

| Clinic | November 13, 2017 | Missile | Syrian Government or Russian Forces |

| Hospital | March 21, 2021 | Aerial Bombardment | Syrian Government or Russian Forces |

Photo: SAMS

A New Subterranean Hospital

Providing health care services in an active conflict is always challenging. In this case, repeated attacks forced SAMS, which supported the facilities beginning in 2017, to move their location many times within a few years. Ultimately, they constructed a subterranean facility in order to provide health care safely for people in need.

The new hospital location was chosen on the outskirts of al-Atareb town, in an effort to reduce the likelihood of airstrikes. The main infrastructure work on the hospital was carried out from March to November 2017, and the new location opened its doors in February 2018.

Photo: SAMS

After moving patient services to the subterranean hospital, between April and August 2018, SAMS rehabilitated the old building in the town center as a comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care center. The old facility and the new subterranean facility remained operational until the assault on northwest Syria by the government of Syria and Russian forces in late 2019. In February 2020, the hospital administration felt al-Atareb town was too close to the front line for patient and worker safety and decided to evacuate both hospital facilities. In April 2020, the resumption of a ceasefire agreement allowed the subterranean hospital to resume service. The old building was converted into a primary health care center (PHC) at that time, and obstetric and newborn care were transferred to the subterranean facility. A satellite vaccination center in al-Atareb town, providing routine immunization for the children in the area, was established in addition to the PHC.

Medical Services in the Subterranean al-Atareb Surgical Hospital

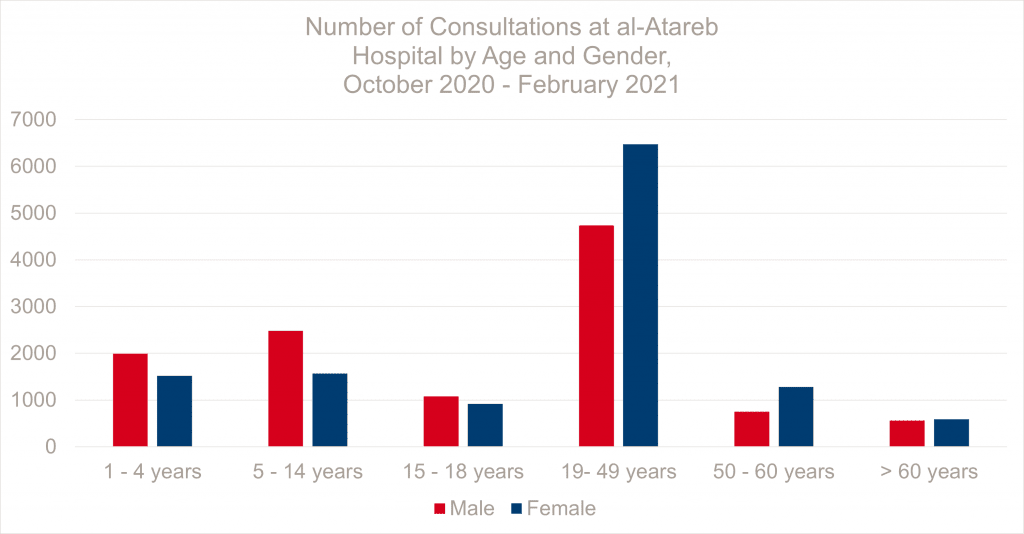

The new subterranean hospital offers a wide range of medical services, including surgical care, outpatient clinics, and diagnostic services. As of July 2021, it has 44 beds, with 20 beds for surgical care and 24 for obstetric and pediatric care. The facility has 89 staff members distributed among various specialties (11 doctors, 30 nurses, 3 midwives, and 9 technicians) to offer medical services to different gender and age groups. Between October 2020 and the end of February 2021, an estimated 21,324 patients benefitted from the hospital’s services, including 10,911 children.

During the same five-month period, the hospital provided services to civilian patients representing a wide range of ages, from neonatal to geriatric patients; 52 percent of those served were women and girls.

The average number of monthly consultations that the hospital offered in that five-month period was 4,791 per month, including 472 reproductive and neonatal care consultations, 63 normal deliveries, 152 non-war-related major surgical procedures, and 1,932 X-ray orders. Other emergency services, such as wound care, average 715 service incidents per month.

“Suddenly, I felt the wall falling over my head, and people were running. I knew at the time that I [had] lost my eye, but I kept running because I didn’t want to die.”

An orthopedic surgeon who was caring for patients at al-Atareb clinic at the time of the attack.

The March 21 Attack on the al-Atareb Subterranean Hospital[7]

On March 21, 2021, at 8:41 a.m., three artillery strikes targeted al-Atareb hospital. One of the shells hit the main entrance courtyard, completely destroying the orthopedic clinic housed in the prefabricated structure at the entrance of the hospital. The shell caused structural damage to the windows of the main hospital and the front gate. Another projectile hit the electric generators on the roof of the hospital, putting them out of service.

That day, 40 patients were scheduled to be seen in the orthopedic clinic. At 8:00 a.m., at least half of the patients were present at the hospital entrance where the clinic is located, each accompanied by at least one family member. Patients were assigned numbers, and clinic staff had begun seeing patients when the first strike occurred and a loud explosion was heard. Patients and personnel near the impact site who managed to survive the strike rushed to seek refuge in surrounding fields.

There was no prior warning about the attack on the facility, and no indication of significant cross-line military escalation or increasing hostilities in nearby areas. The surgical staff were preparing to conduct an elective surgery within the hospital, and patients were being provided routine services. “After hearing a very loud explosion, I ran to the entrance of the hospital,” recounted a female surgical technologist who was in the operating theater preparing a patient for surgery. “Everything was covered with dust so I couldn’t see anything until I arrived at the main gate of the hospital, where the emergency room is located. I saw people on the ground covered with blood. All we could do was to drag them inside and try to help them.”

Photo: SAMS

“Everything was covered with dust so I couldn’t see anything until I arrived at the main gate of the hospital, where the emergency room is located. I saw people on the ground covered with blood. All we could do was to drag them inside and try to help them.”

A female surgical technologist at al-Atareb hospital

Following the first attack, as staff members were helping the injured, and patients were running out of the hospital, the facility was hit two more times. The subsequent attacks resulted in a complete loss of electricity in the facility. All lights and medical devices went off, preventing the staff from providing adequate services to the injured and impeding patient evacuation. Under these challenging circumstances, staff members tried to stabilize the injuries of their patients and colleagues, including a nurse with a chest injury and a technician with a vascular hand injury. Other injuries could not be managed within the facility, such as a patient’s head injury requiring evacuation and admission to an intensive care unit in a nearby hospital. The evacuation of patients and staff was complicated by the continuous threat of subsequent targeting. Civilian cars had to be used to transfer the victims. Patients and hospital staff reported “fearing to leave the building, and not knowing whether we can leave the hospital alive,” according to a male surgical technologist who was about to start his shift when the hospital was hit.

The attack resulted in seven patient fatalities (five men and two children). An additional 17 people were injured, including five medical staff (one doctor, one technician, one emergency room nurse, one COVID-19 triage nurse, and one infection control technician). At least four of the injuries were critical, and the victims were transported to Türkiye for emergency treatment.

Photo: SAMS

Photo: SAMS

Weapons, Perpetrators, and Indicators of Deliberate Targeting

The March 2021 attack on al-Atareb hospital fit into a pattern than suggests deliberate targeting. In addition to the repeated attacks that this facility experienced, there are other indicators of deliberate targeting. Open-source documentation indicates that the Syrian government or its Russian allies were the perpetrators of this attack. The “Krasnopol” shells used in the attack are Russian laser-guided artillery, according to a report published by the Syrian Archive.[8] This munition is known to have been previously used in Syria. Krasnopol shells have a reported range of 15 miles (25 kilometers), with an 80-90 percent accuracy rate. In addition, a video published by a group called “Reverse Side of the Medal,” which has close ties to, and supports, Russian private military companies, showed the moment of the attack captured from an aircraft. Eyewitnesses and staff members who reviewed the video were able to identify themselves as well as the hospital’s landmarks.[9]

“We had to restore the services and reopen the hospital as soon as possible. Each day that passes while the hospital is closed increases the suffering of the people in the area.”

A male surgical technologist at al-Atareb hospital

Deprivation of Access to Health Care

Following the attack, the hospital administration and the supporting NGO (SAMS) decided to evacuate the hospital and immediately begin repair and reconstruction. The hospital recovery phase, which included construction work, cleaning, restoring electrical power, and replacing the destroyed equipment, took approximately two weeks. In the light of the injuries and casualties from the March 21 attack, the leadership of al-Atareb also decided to close the primary health care center, which is located in the town center, to protect the staff and patients there from similar targeting.

“We didn’t want to close the facility, but the damage was substantial,” explained a male surgical technologist at the hospital.

As noted above, al-Atareb health system provides care to patients throughout the region. Residents of al-Atareb town and the surrounding villages were unable to access health care in the hospital for 15 days after the attack. Staff and resources in nearby hospitals were unable to accommodate patients’ needs during this period. Patients reported a three- to four-week wait time for elective surgical procedures at al-Atareb hospital, or to book an appointment in a clinic, compared to the pre-attack maximum wait time of one week. During the time the hospitals were closed, patients were forced to travel 12-19 miles (20-30 kilometers) to access health services in facilities close to the Turkish-Syrian border. These facilities were already overwhelmed with patients, as they serve highly populated areas. Traveling to seek health care from al-Atareb posed both security and financial concerns. The estimated cost for a one-way trip to the nearest surgical hospital was $25, an amount 17 times the average daily income.

“I was following a pregnant woman in the clinic who was scheduled to deliver her baby a few weeks after the attack,” recounted a labor and delivery nurse who was at the hospital when the attack happened. “To continue her prenatal care, her family had to borrow a neighbor’s car to travel to a nearby clinic. They couldn’t afford to rent a car or pay for the trip expenses.”

“We had to restore the services and reopen the hospital as soon as possible. Each day that passes while the hospital is closed increases the suffering of the people in the area,” said the male surgical technologist.

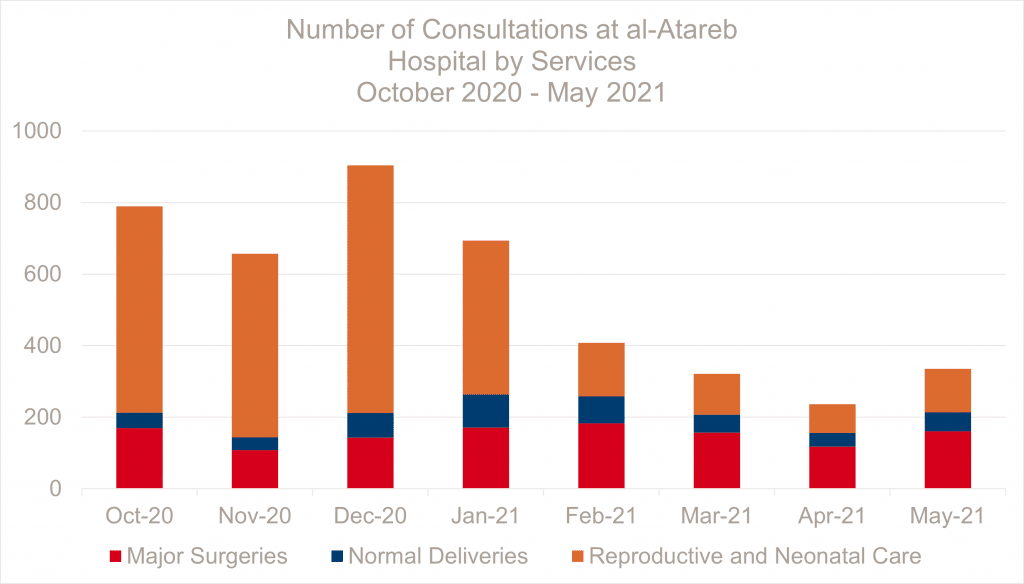

Long-Term Impacts

Al-Atareb hospital remained closed for two weeks until the building was repaired. The vaccination clinic and primary health care center were closed for a week. Even after the hospital reopened, services were not fully restored due to security concerns and the fear of new targeting. The hospital’s administration initially prioritized emergency services but did not restore elective care until a week after the reopening. Many patients were hesitant to visit the hospital to seek advanced care or inpatient services, leading to a decrease in service utilization. However, the services that the hospital provided were so important to the community that utilization picked up over time. The number of consultations dropped to 3,049 in April 2021 and to 4,225 in May 2021 (Monthly average of 3,637 for the two months), well below the average number of consultations prior to the attack (4,791 consultations). The reduction was most pronounced for reproductive and neonatal care, indicating that the impact was greatest for women.

Psychological sequelae of the attack directly impacted health care workers and town residents. Hospital staff and residents of al-Atareb town experienced post-traumatic stress disorder-like symptoms after the attack. Staff members reported to PHR that, for a few weeks, they felt anxious while working in the hospital, and afraid of leaving the building during breaks. Staff described waiting until the end of the day to leave the

| Service | Mean number of consultations prior to the attack (Oct 2020-Feb 2021) | Mean number of consultations after the attack (April-May 2021) | Reduction Percentage |

| Reproductive and neonatal care | 472 | 104 | 78% |

| Normal deliveries | 63 | 46 | 27% |

| Non-war-related major surgical procedures | 631 | 580 | 8% |

| Total consultations | 4,791 | 3,637 | 24% |

| Total beneficiaries | 4,265 | 3,579 | 16% |

hospital, and then doing so as quickly as possible. Despite their high levels of anxiety and stress, hospital staff articulated how important their work is to the community. A surgical technician told PHR, “My children keep asking me to take care of myself while I am in the hospital. I tell them if you get injured, you need someone to help you and therefore my work is important, I am helping others.”

Many members of the staff had experienced prior attacks. Two of the health care workers interviewed had previously worked in Aleppo, where they witnessed the deliberate targeting of health care facilities during the 2016 military offensive that led to the influx of IDPs into al-Atareb area. Both indicated feeling that the targeting of health care facilities and patients remains the same five years later. “You would think that we are safe while working in a big and well-protected hospital, but in fact, no place is safe for health care,” one said.

“We got back to the hospital, where we had worked under threat, and then we forced ourselves to forget.”

A surgical technologist at al-Atareb hospital

Legal Overview

Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) has long documented violations of international humanitarian and human rights law in Syria, including Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions and its Additional Protocols, which prohibit the targeting of those providing and receiving medical care. Based on multiple eyewitness accounts of the March 21 attack on al-Atareb Surgical Hospital, the severity of victim’s injuries, the pattern of repeated airstrikes on multiple health facilities in the frontline al-Atareb region, and the use of highly sophisticated munitions, PHR believes there is a credible basis for a conduct of hostilities charge under the law of targeting.[10]

Three years prior to the March 21 attack, in April 2018, the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) and 11 other humanitarian organizations shared the coordinates of 60 health facilities in Syria with the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ (UN OCHA) deconfliction mechanism.[11] The coordinates for both the “old” al-Atareb facility and the subterranean hospital were included. Once shared, each participating military actor, including the government of Syria and its allies, were to add the coordinates to a “no-strike list.” In theory, these locations were to be considered “deconflicted” or safe from attack, and OCHA pledged to publicly call for an investigation into any alleged violation of the mechanism. The Syrian government forces and their allies knew the location of the facilities and their deconflicted status. Instead of respecting the intent of the deconfliction mechanism, it appears they employed extremely accurate laser-guided missiles to hit al-Atareb Hospital three times in five minutes. PHR believes this demonstrates an intent to kill and injure both health care workers and patients at the subterranean facility. PHR further postulates that the intensity and frequency of the attacks, combined with the apparent intent to kill civilian patients in a hospital facility whose coordinates were known the government of Syria and its allies, may also rise to the level of crimes against humanity as described in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[12]

No less important than the violations discussed above is the right to health, enshrined in Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, to which Syria is a party.[13] This right is also articulated in Article 22.2 of the 2012 Syrian Constitution, providing that “The state shall protect the health of citizens and provide them with the means of prevention, treatment and medication.”[14] As described in this case study, women and children were the most impacted by the March 21 attack, demonstrated by a 78 percent decrease in consultations for reproductive and neonatal care following the attack. By systematically destroying health care infrastructure in al-Atareb sub-district, the Syrian government has effectively deprived the population, including large numbers of vulnerable people, of their right to health.

A Call for Action

Widespread, deliberate attacks on health care facilities and personnel in Syria have continued for 10 years without any meaningful and actionable efforts by the international community to put an end to these crimes. Such attacks on health care not only have a direct impact on the targeted facilities, staff, and patients, they also have long-term negative impacts on the quality of health care and the availability of health services. The situation has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 outbreak, which has further strained Syria’s health system.

The UN Security Council must launch an independent investigation into the attack on the al-Atareb health system, in order to determine the facts of the incident and hold any guilty parties accountable. It is only through accountability that attacks on health in Syria will come to an end. The Security Council should also recognize Syria’s growing humanitarian needs, along with the reduced capacity of the health system due to consistent attacks, and expand humanitarian access in Syria. This includes continued support for cross-border activities, increased oversight of UN funds distributed from Damascus, and sustained efforts to secure principled cross-line assistance.

Donors should prioritize funds for the health system in Syria, including rehabilitation of damaged health centers, procurement of medical supplies, and training for new and existing health workers. Donors should also support mental health services for medical staff, who continue to work under extreme pressure.

Endnotes

[1] Physicians for Human Rights, “Illegal Attacks on Health Care in Syria,” accessed June 30, 2021, http://syriamap.phr.org/#/en.

[2] Orient for Human Relief, “The Surgical Hospital in al-Atareb, Aleppo, Syria,” accessed June 30, 2021, http://orienthr.ngo/ar/surgical-hospital-in-atarib-aleppo-syria/.

[3] United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, “Syrian Arab Republic – Population Statistics, 2004 Syrian Census,” Aug. 15, 2018, https://data.humdata.org/dataset/syrian-arab-republic-other-0-0-0-0-0-0-0.

[4] Assistance Coordination Unit, “The Interactive Study of Population, Displacement, and Return Movement – Northern Syria- February 2021,” accessed June 30, 2021, http://www.acu-sy.org/en/the-interactive-study-of-population-displacement-and-return-movement-northern-syria-febuary-2021/.

[5] Physicians for Human Rights, “Illegal Attacks on Health Care in Syria, Methodology”, accessed June 30, 2021, http://syriamap.phr.org/#/en/methodology.

[6] Physicians for Human Rights, “Illegal Attacks on Health Care in Syria.”

[7] Some of the numbers have changed in comparison with initial press statements by SAMS regarding the attack, after CCTV footage revealed details and the exact time of the assault. The number of fatalities increased after one of the injured passed away.

[8] Syrian Archive, “Guided artillery shells force the Al Atarib Surgical (Al Magahra) Hospital out of service,” Mar. 30, 2021, http://syrianarchive.org/en/investigations/AlMagahraHospital.

[9] Reverse Side of the Medal, Mar. 24, 2021, https://vk.com/rsotm?w=wall-187527798_47326.

[10] For a discussion of the relevant international humanitarian law and customary international law, see Physicians for Human Rights, “Overview of Principles and Rules of International Humanitarian Law Applicable to Conduct of Hostilities with a Focus on Targeting of Hospitals and Medical Unites,” https://s3.amazonaws.com/PHR_syria_map/ihl-methodology-appendix.pdf. For a full discussion of the attacks on medical personnel in Syria, see Rayan Koteiche, Serene Murad, and Michele Heisler, “‘My Only Crime Was That I Was a Doctor’: How the Syrian Government Targets Health Workers for Arrest, Detention, and Torture,” Dec. 4, 2019, https://phr.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/PHR-Detention-of-Syrian-Health-Workers-Full-Report-Dec-2019_English-1.pdf.

[11] Known in full as the Humanitarian Notification System for Deconfliction (HNS4D). For critical discussions of the mechanism in Syria, see A. Levine, ed., “Civilian-Military Coordination in Humanitarian Response: Expanding the Evidence Base, Center for Human Rights and Humanitarian Studies,” Watson Institute, Brown University, Aug. 2020, available at https://watson.brown.edu/chrhs/files/chrhs/imce/research/Civilian-Military%20Coordination%20in%20Humanitarian%20Response_Expanding%20the%20Evidence%20Base.pdf.

[12] Although a full discussion lies outside the scope of this case study, Article 7(1) of the Rome Statute provides several potentially relevant categories under which the government of Syria might be found guilty of crimes against humanity. https://www.icc-cpi.int/resource-library/documents/rs-eng.pdf.

[13] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Syria acceded April 21, 1969. United Nations Treaty Collection “Human Rights: International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights,” https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-3&chapter=4&clang=_en.

[14] Syrian Arab Republic, “Constitution of the Syrian Arab Republic,” 2012, https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/91436/106031/F-931434246/constitution2.pdf.