This report was jointly produced by Physicians for Human Rights, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, and UN Women.

I. Introduction

‘I was targeted because my husband is from a different community that was perceived to hold a differing political opinion from the one of the dominant community we live in.’

Survivor of sexual violence during the 2017 elections interviewed in this research

Electoral-related sexual violence (ERSV) is a form of sexual violence, including rape, gang rape, sexual assault and defilement [1], associated with electoral processes and/or intended to influence or achieve a political end within an electoral process. In Kenya, sexual violence has been a recurrent feature of elections, which have been marred by deadly violence, unrest and serious human rights violations and abuses. Outbreaks of sexual violence during elections have been documented since the 1990s.[2] Following the post-election violence in 2007/2008, the Commission of Inquiry into the Post-Election Violence (CIPEV), known as the ‘Waki Commission’, documented 900 cases of sexual violence perpetrated by security agents, militia groups and civilians against both men, boys, women and girls in a context of large scale violence, mass displacement and more than 1,000 deaths.[3]

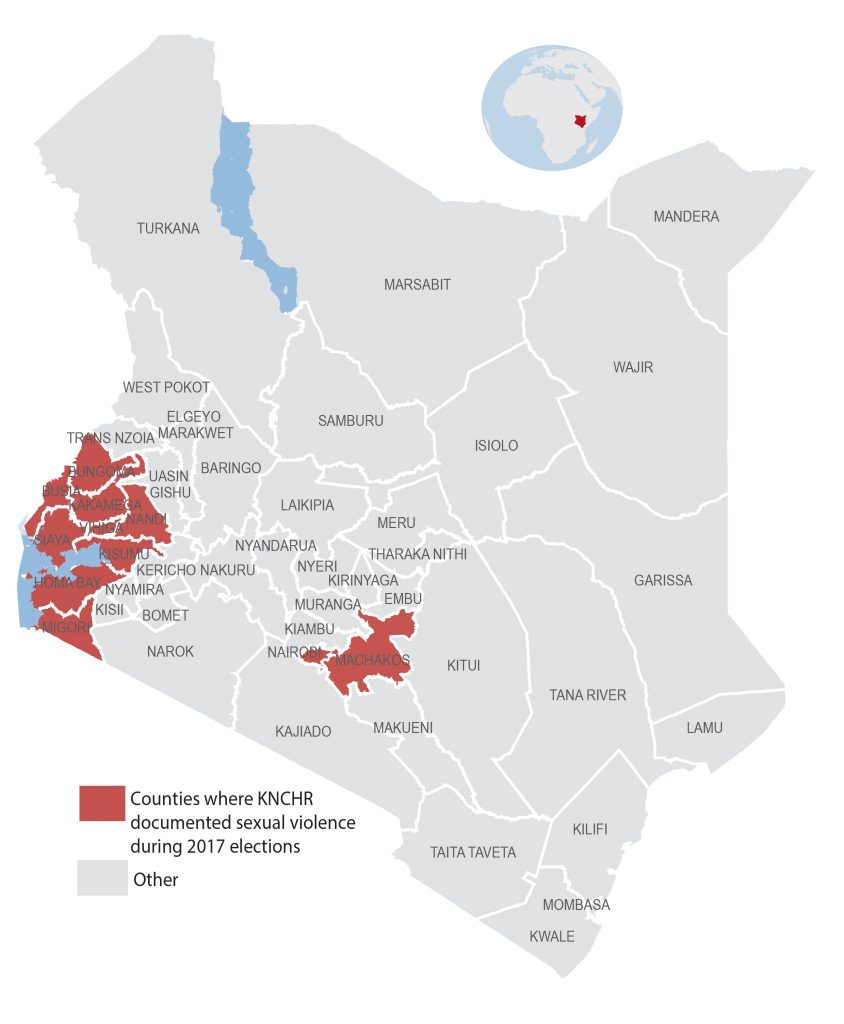

CIPEV provided critical recommendations for reform and was followed by the historic adoption in 2010 of a progressive Constitution with a robust Bill of Rights. Since 2010, an impressive set of laws, policies and standard operating procedures have been developed on prevention and response to sexual violence. Yet, during the general elections held in August and October 2017, within a context of localised violence, large numbers of cases of sexual violence perpetrated by persons in uniform and civilians were again documented. According to the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR), at least 201 Kenyans – most of them women and girls — were subjected to rape and other forms of sexual violence; [4] however the actual figure is likely higher due to under-reporting and the fact that KNCHR documented these in 11 of the 47 counties.

KNCHR, which documented sexual violence during the 2007/08 post-election violence and noted similar patterns in 2017, has characterised ERSV as a premeditated act ‘used as a weapon for electoral-related conflict’.[5] As documented by CIPEV, the Truth Justice and Reconciliation Commission and KNCHR, in Kenya, ERSV has been committed by non-state and state actors, and has targeted political aspirants, their supporters and families, and other civilians, particularly targeting ‘select’ communities owing to their geographical or physical locality and their ethnic origins, which are then directly linked to their perceived political leanings. [6] ERSV is an effort to punish, terrorise or dehumanise communities and individuals, and to influence voting conduct and the outcomes of elections, including by displacing people so that they do not vote. Across different regions and localities in Kenya, common ERSV trends documented in 2007/08 and in 2017 include targeted rape of women and girls following political unrest which forced men to flee, and targeted rape of men and boys. ERSV has also been opportunistic, fueled by a breakdown of law and order and unrest.[7] Ahead of the 2017 elections, there were mass pre-emptive movements of people from their villages due to their fear of being subjected to violence.

Sexual violence is a violation of human rights and fundamental freedoms, and in itself constitutes discrimination.[8] Survivors may suffer the long-term consequences of physical injuries, including fistula and severe vaginal and rectal injuries; sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDs; unwanted pregnancies; stigma and rejection by family members; psychological trauma, including anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder; and loss of livelihoods and educational opportunities.

Understanding the particular characteristics of ERSV is important to aid the proper identification of ERSV and monitoring of trends and patterns, hence bolstering measures for prevention and response in future election periods. In addition to the profound consequences of sexual violence, survivors of ERSV have had to contend with immense barriers in reporting violations, accessing protection and pursuing justice.

Source: Kenya National Commission for Human Rights (KNCHR)

Rationale for the gap analysis study

While Kenya has strengthened its institutional and legislative frameworks, these did not lead to strengthened prevention of and more effective responses to ERSV during the last elections in 2017. It is against this backdrop that the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women) and Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) jointly conducted a comprehensive gap analysis study to review the institutional weaknesses that undermine effective prevention of and response to ERSV in Kenya. Building on KNCHR’s findings on the scale and patterns of sexual violence observed during the 2017 elections, the objective was to build a body of evidence to identify gaps, document good practices and support the formulation of survivor-centred short- and medium-term measures that should be prioritised by duty bearers, especially in the health, security and legal sectors, for effective prevention and response ahead of the next elections in 2022.

This study recognises that Kenya has a high incidence of sexual violence outside election periods. According to the Kenya Demographic Health Survey (2014), sexual violence during non-election years is prevalent in both private and public spheres, with 45% of women and 44% of men aged between 15 and 49 years having experienced sexual and gender-based violence.[9] For this reason, many of the recommendations formulated in this study apply more generally and can serve to strengthen state interventions in election and non-election situations.

Methodology of the study

The study was conceptualised as a human rights-based assessment of gaps and challenges in the prevention and response to ERSV during the 2017 electoral period. The study was conducted by a multi-disciplinary team of six researchers, including gender specialists, a social scientist, and legal and human rights practitioners with expertise in sexual and gender-based violence, access to justice and reparations. Field research was carried out in Nairobi, Kisumu, Bungoma and Vihiga counties, where 85% of ERSV cases documented by KNCHR in 2017 were recorded.

The research employed quantitative and qualitative methodologies.[10] Quantitative data was obtained through a retrospective review of records of Post-Rape Care (PRC) forms and registers at five public and private health facilities within the four counties – Nairobi Women’s Hospital – Gender Recovery Centre, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Referral and Teaching Hospital, Makadara Health Centre (private), Mama Lucy Kibaki Hospital and Vihiga County Referral Hospital – within a three-week period in February 2019. The PRC records reviewed covered the immediate pre-election period [1 July to 6 August 2017], election period [7 August to 31 October 2017], and post-election period [1 November to 31 December 2017], to analyse trends in reporting and responses.

A total of 200 participants from the community, public service, law enforcement, health, forensics, justice, development partners, civil society organisations and ERSV survivors were involved in the qualitative study through extensive key informant interviews and 10 focus group discussions. Two workshops were conducted with stakeholders in April and June 2019 to validate the findings and recommendations of the study.

The study benefited from collaboration with a wide range of Government partners, notably the State Department of Gender Affairs under the Ministry of Public Service, Youth and Gender Affairs, the National Police Service (NPS), constitutional and legislative oversight bodies such as KNCHR, the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA) and the National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC). It also relied upon the testimonies, insights and guidance from survivors’ networks and women’s rights organisations, notably Grace Agenda and Wangu Kanja Foundation. OHCHR, UN Women and PHR are particularly grateful to the 53 survivors of ERSV during the 2017 and 2007 elections, 44 police officers and 95 Government officials from a wide range of institutions that took part in the qualitative interviews.

During the study, the research team put in place stringent measures to ensure meaningful consultations with and participation of rights holders, affected individuals and relevant duty bearers; prevent and mitigate any potential harm to survivors of ERSV and all participants involved in the study; uphold strict standards of confidentiality and security of sensitive information obtained through the study; ensure informed consent of all participants; and maintain impartiality, objectivity and transparency throughout the study.

The research is part of the efforts of the United Nations in Kenya, in partnership with Government and civil society organisations, to stamp out gender based violence including sexual violence against women and girls and men and boys, and advance protection of their rights. It has been undertaken within the framework of the UN Development Assistance Framework 2018-2022 that the United Nations Country Team in Kenya developed in collaboration with the Government, and the Joint UN-Government of Kenya Programme on Prevention and Response to Gender-Based Violence (2017-2022). This research is also an initiative of the PHR Program on Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones, building on its multi-sectoral engagement with and capacity development of service providers to support meaningful access to justice for survivors.

Click here for a more detailed methodology.

II. Kenya’s Human Rights Obligations on Prevention and Response to Sexual Violence

The study is anchored in the human rights obligations that bind Kenya to prevent sexual violence, afford protection to survivors, effectively and promptly investigate and prosecute cases of sexual violence, and provide reparations to survivors.[11] Relevant standards are stipulated in international and regional human rights treaties and conventions to which Kenya is a State Party, including the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), UN International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), African Charter on Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR), and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol). CEDAW, ICCPR, CAT, ICESCR and ACHPR have developed practical guidance on ‘how’ states are expected to effectively prevent, protect, investigate and prosecute sexual violence and provide reparations to survivors of sexual violence.[12] These have been used to measure actions taken by the Government of Kenya during the 2017 election period and discuss findings in the report.

The Constitution of Kenya 2010 has a robust Bill of Rights that safeguards every person’s right not be subjected to ‘any form of violence’ from either public or private sources,[13] as an enforceable right with remedies.[14] It explicitly prohibits discrimination on any grounds, including sex, ethnicity, age and social origin.[15] The Constitution also provides for the right to health, which requires timely, affordable, non-discriminatory access to quality medical assistance for survivors. The right to health includes the collection and management of forensic evidence with the aim of prosecuting cases of sexual violence and providing effective remedies to survivors. Article 38 of the Constitution, read together with Article 81(e), safeguards everyone’s right to exercise their political rights, either as voters or candidates in free and fair elections devoid of violence.

According to the Constitution, international and regional human rights treaties and conventions ratified by Kenya are part of Kenyan law.[16] Under international human rights law, Kenya must adopt and implement necessary legislative, regulatory, institutional and all appropriate measures to prevent, protect, conduct effective and timely investigations, prosecute acts of sexual violence and provide adequate remedies and reparations to survivors of sexual violence,[17] including in elections, committed by State and non-state actors. This obligation is of immediate nature and is to be pursued by all appropriate measures without delay. [18]

Kenya is also bound to adhere to the principles of non-discrimination and ‘do no harm’. The principle of non-discrimination denotes that the rights of survivors must be guaranteed irrespective of their ethnicity, political opinions, health, age, disability, culture and marital status.[19] The principle of ‘do no harm’ denotes that measures undertaken must give priority to the well-being and security of survivors and witnesses of sexual violence and minimise the negative impact of actions to combat sexual violence and its consequences.[20]

Kenya’s human rights obligations continue to apply during periods of unrest or conflict.[21] In fact, electoral periods, which in Kenya are often marred by violence and repeated patterns of sexual violence, require a deliberate effort to implement State obligations with regard to ERSV.

III. Findings of the Study

The findings and recommendations of the study are structured around four areas of State obligations: prevention; protection; investigation, prosecution and ensuring accountability; and access to remedies and reparations.

State Obligations to Prevent ERSV

The State is obliged by human rights treaties and conventions to undertake steps to prevent sexual violence.[22] Specifically, the Government of Kenya is obliged to prevent ERSV through:

- Taking all appropriate measures to prevent acts of sexual violence the authorities are aware of, or to address the risk of violence;

- Establishing a system to regularly collect, analyse and publish data disaggregated by type of violence, so as to further develop preventative measures;

- Developing and implementing awareness-raising programmes with relevant stakeholders countrywide; and

- Providing mandatory, recurrent and effective capacity-building and training for law enforcement officers to equip them to adequately prevent and address violence.

The study established that Government was hampered in fulfilment of its obligation to prevent ERSV due to: 1) lack of anticipation and planning for the risk of ERSV; 2) inadequate coordination and monitoring in implementation of contingency planning; 3) failure to develop and implement survivor-centred, comprehensive and coordinated awareness-raising programmes countrywide; and 4) lack of mandatory, recurrent and effective capacity-building and training for law enforcement officers.

The Government must implement preventive measures with a survivor-centred approach, and design and implement the measures with the participation of women. The Government is also under a duty to allocate appropriate human and financial resources to effectively implement laws and policies for the prevention of sexual violence. The failure of the State to undertake appropriate measures to prevent acts of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), including ERSV, in cases where it is aware or should be aware of the risk of such violence provides tacit permission or encouragement to perpetrate such acts of violence.[23]

Lack of anticipation and planning for the risk of ERSV

The State is mandated to allocate appropriate human and financial resources to effectively implement laws and policies for the prevention of SGBV, including ERSV.[24] Despite patterns of sexual violence in virtually every Kenyan election since the 1990’s, there was a lack of anticipation and planning for the risk of ERSV in 2017 by electoral actors, and resource and capacity gaps in this regard.

The Independent Electoral Boundaries Commission (IEBC), in line with its Strategic Plan (2015-2022) and its Elections Operations Plan (2015-2017), one year ahead of the 2017 elections established a formal partnership with the NPS under its Electoral Security Arrangement Plan (ESAP) to ‘promote and ensure security of campaign periods’ and conduct a ‘joint election risk assessment and response’.[25] However, IEBC’s Strategic Plan and Elections Operations Plan focused on the risks of general violence and did not integrate an assessment of the risk of ERSV. Consequently, the ESAP did not explicitly include a risk assessment of ERSV, and rather focused on the security of electoral materials and candidates, and on tackling the risk of general violence during the election.[26] The IEBC respondents interviewed indicated that they did not have specialized technical gender capacity to undertake thorough contextual analysis and hot spot mapping that would identify possible triggers and ERSV risks against electoral timelines, noting that each phase of the electoral process carries different risks.

The IEBC has a duty to ensure adherence to codes of conduct by political parties, their candidates and members during the electoral period and to take steps to prevent violence and respect human rights.[27] In 2017, IEBC developed a Code of Conduct for nominations by political parties as provided in the Elections (Party Primaries and Party Lists) Regulations 2017. This code, together with three other Codes of Conduct provided in the IEBC Act, the Elections Act and the Political Parties Act, all proscribe violence, harassment and intimidation by candidates and political parties.[28] IEBC established a partnership with the Office of the Director of Public Prosecution (ODPP) to monitor compliance with these codes of conduct. However, due to inadequate resources, the partnership was only operationalised on the day of elections and focused on monitoring at polling stations. It excluded the key phase of the primary elections in April 2017, during which a large number of women candidates experienced verbal and physical attacks, and threats of sexual violence. Women candidates interviewed by the research team observed that threats of sexual violence and sexual assault directed at women during the electoral period often escalate to ERSV and called for such threats and assaults to be prevented and addressed. A woman candidate during the 2017 general elections aptly stated, ’I did not see IEBC monitors or any monitors. As a candidate, I was sexually harassed as my breasts were touched on several occasions during campaigns. Sexual violence escalates from such forms of sexual assault…’.

Political parties have a duty to ensure adherence to codes of conduct, to respect human rights and to publicly condemn, avoid, refrain from, and take steps to prevent violence.[29] Political parties did not establish effective internal dispute resolution mechanisms for receiving complaints of threats and ERSV, and for enforcing compliance with the Political Parties Act code of conduct. Interviewed women candidates indicated their political parties’ dispute resolution mechanisms had high thresholds for evidence, requiring corroboration to address threats of violence, including ERSV, and, as a result, their cases were largely unaddressed. A woman respondent, who was a political party agent during the 2017 general elections, told the research team that she received several threats of sexual violence for being an agent for ‘the wrong political party’ and informed her political party of these threats but did not receive any assistance, although the provision of security is stipulated under the codes of conduct. After a series of such threats, she was raped.

State security officers were deployed countrywide as part of security planning. However, the officers did not receive specific pre-deployment briefings on how to deal with risks of and respond to ERSV. The 2017 general elections saw a massive deploymentof 180,000 officers drawn from the NPS, as well as special police officers deployed as reinforcement from the Kenya Prisons Service, Kenya Wildlife Service, Kenya Forest Services and National Youth Service. NPS general security planning focused on ‘crime prevention and response during electoral period’. NPS respondents noted this would be enough to prepare for risks of sexual violence. Some security officer respondents said, ‘in cases where sexual violence is perpetrated during riots, police contain riots to ensure sexual violence cases are not escalated, as a mitigation measure.’ Senior NPS respondents observed that it was not possible to know where and when ERSV would take place since ERSV is a ‘private crime’, and it did not warrant any kind of specialized mechanisms beyond the general crime mapping. As discussed in the next section on protection, due to this gap in planning for the risk of ERSV, safe corridors were not put in place during periods of containment to enable survivors to seek safety and medical assistance.

Inadequate coordination and monitoring in implementation of contingency planning and absence of ERSV data collection system

The State must, when undertaking appropriate measures to prevent sexual violence, coordinate with relevant actors and undertake regular monitoring so as to enhance the prevention of such violence.[30] The Government is called upon to ensure civil society organisations, including community organisations, directly participate in an ongoing manner in prevention activities and in all stages of the development, implementation and monitoring of action plans.[31]

A National Contingency Plan for the 2017 general elections was developed by the National Disaster Operations Centre, located in the Ministry of Interior and Coordination of National Government. The plan was developed in collaboration with key Ministries, State, non-state, development and humanitarian actors. It was premised on lessons learned from the 2007/2008 post-election violence.[32] The planning process commenced in August 2016, one year before the elections, and was intended to cover the pre-election to post-election period from March to November 2017. The National Contingency Plan acknowledged sexual violence as one of the gaps and challenges to prioritize for preparedness and response,[33] and consisted of four inter-related pillars: early warning and prevention; security and safety; humanitarian assistance; and mass casualty incidents. Key actors working in these four sectors were required to develop specific preparedness and response plans to be annexed to the National Contingency Plan.

However, despite the prioritization of addressing sexual violence, there were challenges and gaps in implementation:

- Sexual violence was unevenly prioritised in the implementation of the National Contingency Plan (see details in following section on protection);

- Implementation of the plans was undermined by funding delays, as close as three to four weeks prior to elections (see details in following section);

- Due to weak coordination between election observers, such as Uwiano Platform for Peace, and other actors, such as KNCHR and civil society organisations, documented information on risks and actual patterns of ERSV was not integrated in early warning, prevention and contingency plans under the IEBC Inter-Agency Coordination Committee composed of relevant line ministries for information sharing on election security risks.

KNCHR did not receive earmarked Government funding to enable it carry out countrywide human monitoring during the 2017 elections period but was able to deploy over 100 human rights monitors with financial support from development partners. Whilst NGEC and KNCHR both deployed monitors, they did not coordinate monitoring throughout the electoral period, to exercise their complementary roles as stipulated in the Constitution and in their constitutive Acts.[34] NGEC deployed monitors to implement a tool on the political participation of marginalised groups, but its monitors (two in each of the 47 counties) were not utilised to monitor ERSV.

The State is required to establish a system to regularly collect, analyse and publish data categorized by type of violence so as to further develop preventative measures.[35] The NPS indicated to the research team, however, that while police stations gather data on age, gender and types of gender-based violence, the data is only processed annually for statistical purposes. Thus, data collected during the electoral period was not analysed in real time so as to enhance election contingency plans and early warning systems for the prevention of ERSV.

Failure to develop and implement survivor-centred, comprehensive and coordinated awareness-raising programmes countrywide

The State is obliged by human rights treaties and conventions to develop and implement awareness-raising programmes targeting women and men at all levels of society to prevent sexual violence. Such programmes should provide information on relevant laws, encourage reporting of sexual violence, and provide information on mechanisms available to report acts of violence and measures to protect, assist and support victims.[36]

The study found failure to develop and implement survivor-centred, comprehensive and coordinated awareness-raising programmes countrywide. The study established that while awareness-raising activities were conducted by State actors prior to the election period, activities were:

- Uncoordinated, resulting in duplication;

- Not carried out countrywide due to limited resources. Respondents from Government and civil society organisations indicated that their selection of target counties was often based on availability of staff in those counties due to resources constraints. Awareness-raising initiatives were reported to be minimal in Bungoma and Vihiga counties, which saw high prevalence of sexual violence in the 2017 elections;

- Neither standardised nor comprehensive, and were disseminated late, at times two to three weeks prior to the general elections, due to delayed receipt of donor funding. As discussed in detail in the following sections, awareness-raising materials lacked practical information on several key aspects, such as how to preserve evidence and report cases to the NPS Internal Affairs Unit and IPOA.

Lack of mandatory, recurrent and effective capacity-building and training for law enforcement officers

The State is required to provide mandatory, recurrent and effective capacity-building and training for law enforcement officers to equip them to adequately prevent and address sexual violence. Training should focus on different types of sexual violence and on how to detect and prevent them, and should centre on the rights and needs of survivors.[37]

The study found failure to provide mandatory, recurrent and effective capacity building and training for law enforcement officers. The study established that the Government had instituted efforts to conduct training for law enforcement agencies, but these had challenges and gaps:

- Trainings conducted for the NPS and security officers drawn as reinforcements from other services largely focused on preparing security personnel in case of riots or demonstrations, and criminal investigation of election offences such as voter bribery, but did not provide operational guidance on their role to prevent and respond to sexual violence;

- The NPS does not provide training to police officers on how to proactively detect risks for sexual violence, enhance protection during outbreaks of violence or perform other tasks such as escorting survivors to safe places. Police P officers who were interviewed confirmed that their standard basic training focuses on ‘investigation’ and sexual violence is largely treated as any other crime. There are no specific instructions on how to prevent re-traumatisation or management of forensic evidence in the chain of custody during unrest or in the context of late reporting by survivors;

- The NPS Standing Orders, which contain elaborate provisions on how police officers should receive and act on complaints from survivors of sexual violence, were finalised in July 2017 and therefore were not reflected in training provided before the August 2017 elections;[38]

- Police respondents indicated that between electoral cycles a number of police officers receive ad hoc specialised training on sexual violence by civil society organisations and UN agencies. However, the content of training is not harmonized, police are not sufficiently consulted to ensure training addresses NPS training needs assessments, and there is no database of police officers who have received specialised training so as to specifically assign them to gender desks in police units.

Good practice: In February 2019, the NPS launched its ‘Standard Operating Procedures on GBV Prevention and Response’ that aims at ‘in-service training for serving police officers and new recruits as a stand-alone program, in all County Police Training Centres and Regional Training Centres’ and ‘establish a database of officers trained in GBV preventive and responsive policing’.

State Obligations to Protect

The State is obliged by human rights treaties and conventions to provide timely, accessible, affordable, adequate, appropriate and efficient measures to protect survivors and individuals at risk for new acts and consequences of sexual violence.[39] Under these treaties and conventions, the Kenyan government is obliged to protect individuals from ERSV through:[40]

- An effective legislative, policy and regulatory system, with adequate institutional mechanisms and budgetary and human resources for protective measures;

- Safety and security measures, such as crisis support, rescue and referral centres, safe houses and shelters, and confidential reporting mechanisms to protect victims and their families from stigmatisation and reprisals, regardless of whether they have lodged a legal complaint;

- Emergency response measures, including 24-hour toll-free helplines, rescue and rapid health care services, crisis counselling, referrals and linkages to comprehensive follow-up services;

- Comprehensive health care, including sexual and reproductive health care, to address physical and psychological trauma, and medical forensic services;

- Legal and socio-economic assistance to support victims and survivors in accessing remedies for ERSV and restoring their livelihoods, including provision of transportation, skill-building training, employment opportunities, education, childcare and affordable housing.

The study found that the State has established various protection measures, but the Government was hampered in its fulfilment of its obligations to protect ERSV survivors by: 1) delays in implementation of laws and national policies; 2) failure to establish safety and security measures for survivors; 3) inadequate preparation of emergency response to ERSV; 4) failure to ensure access to affordable, appropriate, quality and comprehensive health care services; 5) ineffective access to information on availability of protection measures and services; and 6) lack of coordination among stakeholders in the design and implementation of measures for protection and assistance to survivors.

The State has a duty to ensure that protection measures are accessible to all victims and survivors of ERSV, without discrimination on any basis, in all locations. These obligations are applicable at all levels of Government, including within devolved county governments. The Government must, therefore, ensure that county governments are allocated adequate financial, human and other resources to effectively and fully implement protection measures for victims and survivors of ERSV; the Government must retain the authority to require compliance, coordination and monitoring within devolved governments.[41]

Delays in implementation of laws and national policies, resulting in ineffective protection and assistance to survivors

The Victim Protection Act No. 17 of 2014 provides for assistance and protective measures to victims of crime, including security, rehabilitation, health, psychological and psychosocial support, legal services, transport, childcare and other appropriate assistance to manage physical injuries and emotional trauma, facilitate access and participation in criminal and restorative justice processes, obtain reparation, and deal with consequences of victimization.[42] However, the draft Regulations required to operationalize the Act were prepared prior to the 2017 elections, but were not finalised and gazetted.

The Government has not developed operational frameworks to ensure effective implementation of and resource allocation for protection measures outlined in the 2014 National Policy on Prevention and Response to Gender-Based Violence. These measures include safety and security, psychosocial support, socio-economic assistance, legal aid and referral services for victims and survivors of sexual violence. Further, the Multi-Sectoral Standard Operating Procedures on Prevention and Response to Sexual Violence 2013 are yet to be operationalised to institutionalise follow up and referral mechanisms for medical, psychosocial support and protection services to survivors; thus, referral and follow up are ad-hoc depending on clinicians’ knowledge of other service providers. The Government has also yet to finalise and adopt a policy on the uniform treatment of all sexual offences envisaged under Section 46 of the Sexual Offences Act.

Further, the national policies on Gender-Based Violence and Health have not yet been adopted into the laws of the four county governments where the study was conducted, resulting in inadequate resource allocation and provision of protective measures.

Failure to establish safety and security measures for the protection of survivors

The State has a responsibility to create or fund safety and security measures for survivors of sexual violence. Such measures should be accessible to all survivors and their children or families; be provided at no cost and regardless of whether a survivor has lodged a legal complaint; guarantee absolute safety, privacy and confidentiality; and be sufficiently funded and staffed with competent personnel.[43] ERSV survivors in Bungoma told the research team they refrained from reporting ERSV because of reprisals from perpetrators and due to numerous, repeated and unabated threats or attacks by well-known gangs in the area during the electoral period.

There is no Government-established safe shelter; therefore clinicians indicated that they referred ERSV survivors to safe shelters run by civil society organisations, which can only offer protection for a few days and often lack the capacity or resources to provide protection for survivors together with their children or spouses. In some instances where emergency shelter was available,survivors were fearful of leaving their children behind without anyone to provide them with care, food and security.In some cases, child survivors were referred to borstal institutions/juvenile centres due to the lack of alternative shelters that would be more appropriate for their protection.

Insufficient time, resources and expertise to implement the National Contingency Plan to effectively anticipate and prepare for emergency response for survivors of ERSV

The State has a duty to ensure adequate protection and accessibility of emergency health care and protection services to survivors. This includes the development and dissemination of standard operating procedures and referral pathways to link security actors with service providers offering medical, legal, psychological, and socio-economic assistance.[44] The study found there was a failure to ensure adequate protection and accessibility of emergency health care and protection services to survivors.

The National Contingency Plan required agencies under its humanitarian pillar to work closely with agencies under the early warning, security and health pillars to provide safe access to affected populations and coordinate health services in emergency situations. However:

- Operationalization of the plan at the county levels through the 8 regional hubs, County Disaster Committees and Steering Groups commenced too close to the elections, leaving insufficient time for effective county risk assessments, planning, adequate training, simulations and coordination with key actors and stakeholders from regions and communities that were likely to be affected;

- Technical assistance to support provision of protection and emergency response measures for ERSV and other forms of SGBV was not available until September and November 2017, several weeks after the outbreak of election-related violence following the general election in August 2017 and fresh presidential elections in October 2017;

- Greater attention was placed on mitigating and addressing internal displacement, loss of life, serious physical injuries and destruction of property, in comparison to sexual violence. As a consequence, most of the responses to reported cases of ERSV were reactive and initiated well after the violence had erupted;

- The national and county contingency plans failed to contemplate the effect of containment (the blocking of roads as a security measure to quell violence in affected communities) on the access of survivors of ERSV to emergency health care, safety and other protective measures. There was no coordination between first responders, humanitarian agencies and security actors to provide safe access into and out of affected communities, and safety for survivors, humanitarian workers and volunteers. A respondent described the chaotic situation, “youth were throwing stones and police were throwing tear gas”. The heavy presence of security personnel instilled fear within the affected communities;

- The national and county governments did not put in place effective contingency measures for health and psychological support services for survivors of ERSV, in light of the doctors’ and nurses’ industrial strike that was ongoing during the electoral period. Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital Gender-Based Violence Recovery Center in Kisumu County was the only one of the four public health facilities reviewed during the research that was operational during the electoral period.

A civil society-based national toll-free helpline, 1195, which is manned 24 hours by Healthcare Assistance Kenya (HAK) provided confidential reporting support to survivors of ERSV.

However, the State did not provide it with additional personnel or resources in anticipation of ERSV cases. HAK responders were overworked some handling 36 hour shifts, lines were reported to have jammed following elections and there were no follow-up mechanism for the helpline to establish survivors received protection, medical and support services.

As a result of these challenges in the implementation of contingency plans, 29 out of 39 survivors who reported ERSV during the 2017 elections and who were interviewed in Bungoma, Vihiga, Kisumu and Nairobi counties were unable to access medical care, and two survivors contracted HIV and other STDs as a consequence of delayed medical treatment. Three of the 39 survivors were minors, and one conceived a child as a result of rape.

Failure to address existing structural, resource and capacity gaps to ensure access to affordable, appropriate, quality and comprehensive health care services, including sexual and reproductive health care, psychological care and medical forensic services.

- National policies, guidelines, regulations and Standard Operating Procedures for provision of PRC health services have yet to be fully adopted and implemented within Nairobi, Kisumu, Vihiga and Bungoma counties as envisaged under Section 15 of the Health Act No. 21 of 2017. As a result, there were no earmarked or sufficient resources allocated within the budgets of county governments to ensure provision of available, accessible, appropriate and high-quality PRC health services. County governments were heavily dependent on grants from donors for the implementation of health policies, resulting in a heavier focus on areas of donor interest such as maternal health and HIV.

- Most health facilities do not provide 24-hour specialized, integrated and comprehensive medico-legal services. Survivors who report after 5 p.m. are often received through the casualty ward and only provided with emergency contraceptives, PEP kits and treatment of serious injuries. Most survivors do not return to the facility for follow-up treatment and psychosocial support due to lack of fare. A health professional respondent noted ‘“The return rate for the second visit is at 80%; but by the fifth visit the rate of follow up visits decreases to 28%. Once the survivors complete their PEP dosage and confirm that they are not pregnant or HIV-negative they begin to fall out.’

Good practice: The study established promising strategies for survivor-centred comprehensive medical treatment and follow-up. Nairobi Women Hospital-Gender Violence Recovery Centre reported that it has been able to improve the rate of survivors return to 90% through sustained phone calls, establishment of additional branches to enhance accessibility, and database of network of hospital, state and non-state actors countrywide for referral of survivors for follow up health care, safe shelter and legal aid.

- Misconceptions that men are incapable of being raped and stigma about being perceived as weak hindered male survivors from reporting violations. “Adult male survivors shy off from reporting ERSV. They are ridiculed at different service points and by their peers. They only come forward when very severely injured, such as a case where a man had his testicles cut off and became suicidal,” stated a hospital administrator in Nairobi. PRC records reviewed confirmed the effect of gender stereotypes, as the records indicated that 5% of the total reported cases involved male survivors.

- There are regular shortages or complete lack of essential medicines, commodities and equipment for provision of PRC services. Two of the reviewed health facilities reported that they had not had emergency contraceptives for almost five months. Health professionals said they lacked PRC supplies.

- Respondents reported that survivors are charged for completion of P3 Forms (police forms to be completed by medical officers) by medical examiners in public health facilities, and in some facilities they have to pay for laboratory services and prescribed medication in violation of Section 35 of the Sexual Offences Act No. 3 of 2006, which entitles survivors to receive free medical treatment from public health facilities and gazetted private hospitals.

- Survivors did not receive ongoing psychosocial support, counselling, or peer and community support to deal with trauma and reduce stigmatization. Health professionals reported that they were only able to facilitate or provide survivors with counselling during HIV testing and follow up on PEP adherence within a three-month follow-up period.

- The absence of clear and standardised policies and guidelines for provision of abortion services to survivors who became pregnant as a result of rape presents barriers to access to timely and non-discriminatory abortion services. In some cases, there are requirements for pre-authorization, which contradict Article 26(4) of the Constitution. A health care worker reported that clearance from five doctors was required to recommend the provision of safe abortion to survivors who became pregnant from rape: “In some cases, survivors come back to the hospital for post-abortion care after performing back street abortions”.

- There are inadequate resources for effective collection, documentation and preservation of medical forensic evidence and chain of custody. The five health facilities assessed during the study did not have pre-assembled and standardized rape kits. Health professionals also reported persistent shortages in supply of the comprehensive PRC forms used for standardized examination, collection and documentation of medical forensic evidence. Health professionals were also reluctant to give evidence in court proceedings following completion of PRC forms because they often have to pay for their own transport costs.

- Lack of harmonization and consistent practice in the completion and use of medical PRC and police P3 forms present challenges to the comprehensive documentation of medical evidence, result in double reporting or conflicting information, and often expose survivors to re-traumatisation when re-examined for the purpose of filling out both forms separately.

- Due to inadequate resources for training by the Ministry of Health, there is only a small cadre of competent clinicians available to provide post-rape care services, which is inadequate compared to the number of reported cases of sexual violence and even more so during emergency periods.

Public health facilities lack safe, private and gender-sensitive facilities for examination of survivors of sexual violence. A clinician in one facility described, “When a survivor reports through outpatient, clinical officers have to get one of their colleagues out of the triaging room in order to have privacy while examining the patient… sometimes, I just have to examine the patient in my office.” Another observed challenge within the facilities was that, at times, sexual violence cases are referred to the Maternal Child Unit which creates a barrier to male survivors who would fear reporting their cases in midst of women and children.

Ineffective access to information on availability of protection measures and services

The service provider directory developed and disseminated by UN Women and its partners, including the State Department for Gender Affairs, was only available a few weeks prior to August 2017 due to delayed disbursement of production, hence there was not sufficient time to test and ensure all functional service providers at community level were included in the directory. Respondents reported that some of the service providers’ contacts were not operational during the electoral period.

Absence of coordination, including with community-based actors, in the design and implementation of measures for protection and assistance to survivors.

The absence of coordination resulted in parallel, disjointed and duplicative response efforts being conducted by different organisations, within existing programmes run by County Technical Working Groups, Court Users Committees and the NGEC GBV working groups. Further, the implementation of the National Contingency Plan was heavily driven by humanitarian and development partners, with minimal involvement of community and non-state actors, and assumed that survivors would readily access emergency protection and support services. Human rights defenders, who were the most vital first responders to the majority of ERSV survivors within affected communities, were not effectively utilised by state actors under the National Contingency Plan.

The study also noted promising practices whose effectiveness can be improved upon to address challenges of insufficient resources, inadequate time for planning, weak linkages, lack of knowledge among survivors on response and referral mechanism, well acknowledged by the survivors’ first responders. In Nairobi, the national network of survivors of sexual violence monitored electoral activities and reported signs of risk of violence to the Wangu Kanja Foundation, which collaborated with key stakeholders, including police, County commissioners, churches, and other actors, and provided safe shelters to support access to protective measures for survivors of sexual violence. Also in Nairobi, the Election Observation Group (ELOG) referred cases of ERSV reported by its monitors to the Centre for Rights Education and Awareness, a CSO, which subsequently facilitated survivors’ access to emergency health and psychological care, legal assistance and psychosocial support.

Kisumu had a promising coordination the Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Referral and Teaching Hospital and the County Technical Working Group trained community health volunteers and actors to sensitise survivors in affected communities on the importance of reporting and create awareness on health care and other protection measures available through its Gender-Based Violence Recovery Center. Through these community awareness campaigns, several survivors were identified and eventually sought health care. In Vihiga County, a Red Cross volunteer established base at a shop within an informal settlement that was experiencing violence and ferried emergency contraceptives and HIV post-exposure prophylaxis to survivors using a motorbike through the bushes.

State Obligations to Investigate, Prosecute and Ensure Accountability

The State is obliged to take all appropriate measures to investigate, prosecute and apply appropriate legal and disciplinary sanctions to ensure accountability for violations of human rights, including acts constituting international crimes, as part of the obligation to provide access to effective remedies.[45] The obligation to prosecute and provide adequate remedy for ERSV includes:

- Effective laws, institutions and a system in place to address sexual violence committed by State and non-state actors.[46]

- Eliminate barriers to access to justice and guarantee essential components of access to justice for survivors of ERSV such as accessibility; effective, accountable and gender-responsive justice institutions; and just and timely remedies.[47]

The study established that Kenya has an overall impressive legal and institutional framework in place to investigate, prosecute, and establish accountability for sexual violence in Kenya, including during elections and other situations of unrest. However, the Government was hampered in fulfilling its obligations due to: 1) lack of specificity, linkage and a confusing duality in the legal framework criminalising and sanctioning ERSV in Kenya; 2) inaccessibility and unavailability of reporting and complaints response mechanisms to ERSV survivors; 3) failure to conduct survivor-centred, timely and properly resourced investigations; 4) ineffective coordination between investigative agencies; 5) weak linkages with organisations working with survivors; 6) limited specialised prosecution capacity; and 7) lack of effective data collection throughout the criminal justice system.

To date, there have been no completed prosecutions, adjudication and convictions for cases of ERSV arising from the 2017 election period or from the 2007/2008 post-elections violence. Gaps and challenges noted relating to 2007/2008 ERSV persisted following the 2017 elections, and must be addressed urgently to ensure accountability. Accountability is an important element of prevention of future violations.

Lack of specificity, linkage and a confusing duality in the legal framework criminalising and sanctioning ERSV

The State is obliged to adopt legislation[48] prohibiting all forms of gender-based violence against women and girls, including by the criminalisation of sexual violence, in line with international standards. However, under Kenya’s legal framework:

- There is no definition of ERSV, which hampers the identification and treatment of ERSV as a unique and particular manifestation of sexual violence requiring specific investigation and prosecution, especially in cases of targeted, widespread or systematic sexual violence.

- The Election Offences Act prescribes lesser penalties for sexual violence in comparison with the Sexual Offences Act, which is the law under which sexual violence is investigated, prosecuted and punished in Kenya therefore creating a duality in punishing sexual violence.

- The Election Offences Act does not make any linkage with the Sexual Offences Act so as to guide the investigation and prosecution of wide-ranging forms of sexual violence outlined under the Sexual Offences Act, which could be perpetrated and manifest as ERSV.

Inaccessibility and unavailability to ERSV survivors of reporting and complaints response mechanisms

The State is obliged to ensure access to information to support access to justice.[49] The study found that Kenya has robust reporting and complaints mechanisms – such as the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA), Police Internal Affairs Unit[50] (IAU) and the Witness Protection Agency[51] (WPA) – but there were challenges and gaps in ERSV survivors accessing these mechanisms.

- Despite the documented prevalence of ERSV in past elections, there were no specific contingency measures established, such as an ad hoc reporting centre, to facilitate the reporting of ERSV to police during the 2017 electoral period. The majority of ERSV survivors interviewed indicated that police stations or patrol bases were too far from their villages and inaccessible during the period of unrest following the initial announcement of presidential election results.

- Survivors and community members did not have information on the existence and mandates of IPOA and IAU (a specialised oversight unit within NPS), as special complaints mechanisms available to investigate ERSV perpetrated by police; and on WPA as an available protective mechanism.

- Prior to the 2017 elections, 49 out of the 53 survivors interviewed were unaware of the existence and mandate of IPOA. Four of the 53 survivors were aware of IPOA as a result of awareness raising by various NGOs. After the 2017 elections, 10 of 49 survivors who were unaware of IPOA became aware of its existence after IPOA investigators approached six of those survivors in Kisumu to follow up on the reports they had made to local police stations regarding ERSV perpetrated by police. None of the 53 survivors interviewed were aware of the existence and mandate of the IAU. IAU investigators indicated to the research team they had not received any reports from members of the public on police-perpetrated ERSV. 44 of the 53 survivors interviewed were unaware of the existence and mandate of the WPA.

- There were inadequate resources to ensure the operational devolution of IAU to the county level, to improve their accessibility and availability to communities. IPOA has devolved offices in Kisumu and Kakamega counties that also cover Vihiga and Bungoma counties. Avenues for reporting to the IPOA and/or the IAU include telephone, email, mail and reporting at a police station, field office or the Office of the Ombudsman.[52] These avenues are limited and inaccessible to persons who cannot afford mobile telephone airtime or internet costs, or fare to travel to the offices far from their locality.

- ERSV survivors reported that they were not apprised of the progress of investigations in their cases. Therefore, they were apprehensive that they may not secure justice.

- Perceived corruption within the police and unaddressed security concerns amongst survivors’ communities also discouraged survivors from reporting ERSV cases to the police.

Failure to conduct survivor-centred, timely and properly resourced investigations

The State is obliged to ensure that investigations are prompt and expeditious;[53] independent and impartial;[54] transparent to allow for public scrutiny and victim participation;[55] thorough and aimed at uncovering the facts of what happened;[56] and capable of identifying and punishing those responsible.[57] Victims ought to be informed of and have access to hearings and all relevant information on the investigation.[58] States must also guarantee that the rules applicable to gathering and using evidence do not discriminate against survivors of sexual violence.[59]

The study uncovered serious gaps and challenges resulting in an inability to carry out survivor-centred, timely and competent investigations of ERSV cases due to:

- Inadequate technical capacity, knowledge and skills within investigative agencies to handle cases of ERSV;

- Absence of effective systems, procedures, measures and safeguards to facilitate investigative agencies to undertake effective investigations into police-perpetrated ERSV; and

- Failure to address existing structural, resource and capacity gaps to the conduct of prompt, thorough and effective investigations of sexual violence during non-election years.

Inadequate technical capacity, knowledge, skills and competence within investigative agencies

The State is obliged to establish diverse institutional measures, which are competent and properly resourced, to enforce laws combating sexual violence. Measures include the establishment and adequate funding of specialised units, which are staffed with properly trained and specialised officers.[60] IPOA, IAU and NPS indicated that they had not received specialised and continuous training, and therefore lacked technical capacity, skills, competence and knowledge on distinct forms, types and manifestations of ERSV and the specialised investigations required. This hampered investigations of ERSV following the 2017 elections. The study noted:

- Investigators from the NPS, IPOA and the IAU placed heavy reliance on reporting by survivors in order to initiate investigations into ERSV. This was regardless of information being available within the public sphere on widespread or systematic ERSV in 2017.[61] Police respondents indicated they could not commence investigations unless a report was filed, as it would amount to “actively engineering reports”. This approach did not take into consideration that the NPS, IPOA and IAU can initiate investigations on their own motion.[62]

In 2018, IPOA proactively visited a number of 2017 ERSV survivors in Kisumu to record their complaints after the survivors filed complaints with different police stations in Kisumu. However, the survivors indicated that since then, IPOA has not shared any feedback.

Similarly, upon receiving instructions from the Inspector General, the NPS Internal Affairs Unit conducted a visit to Kisumu in 2018, drawing on the findings of civil society organisations on ERSV perpetrated by police in 2017, namely Human Rights Watch and the Wangu Kanja Foundation. This resulted in an internal report that recommended further investigations by the Directorate of Criminal Investigations and IPOA.

- A section of police officers interviewed were unaware of protective and other support measures which are in place for the benefit of ERSV survivors. Nine of the 44 police officers interviewed were unaware of protective mechanisms such as the Witness Protection Act[63] for the benefit of victims of crime, including survivors of ERSV. Twenty of the 44 police officers interviewed, even though aware of the WPA, were unaware of the procedure to invoke its mandate towards supporting investigation and prosecution of ERSV cases.

- Some survivors reported having been treated by police officers in an insensitive manner. Survivors were asked distressing and shame-inducing questions by multiple investigating officials and were not allowed to lodge complaints when they could not identify perpetrators. In other cases, they were sent away from police stations once they stated they were reporting cases of ERSV involving police.

- Contrary to the provisions of the ‘Police Manual’ requiring investigations of crimes regardless of where a report is made or originates, police officers indicated they would only take up investigation of sexual violence that occurred within their own jurisdiction. This does not take into account that survivors – for security or economic reasons – may need to report to their nearest police station, which is not necessarily in the area where the crime occurred.

- There was a lack of understanding within the investigative agencies that investigations should proceed even if the perpetrator’s identity is unknown. Police indicated such cases are marked pending under investigations, with no movement, unless survivors provide further evidence.

- There was lack of knowledge on the specificities of sexual violence occurring during conflict or periods of unrest, including its types, trends, patterns, and the prevailing context within which ERSV occurs. The knowledge is essential for:

- Conducting thorough and targeted investigations into ERSV and pursuing criminal accountability for commanders under whose command ERSV allegedly occurred within a certain area or locality, when the identity of individual police perpetrators cannot be established. Members of IPOA and IAU who were interviewed stated that in cases where the identity of alleged perpetrators was not known, and where additional evidence had not been availed by the survivor to assist in the identification of the alleged police perpetrators, they were unlikely to pursue investigations owing to the difficulties anticipated in identifying the perpetrators, since Kenya does not have DNA or fingerprint databases.

- Not placing the burden of investigations on survivors and requiring them to provide corroborating evidence. Survivors reported that where forensic medical evidence was unavailable, police officers required them to secure corroborating evidence, such as identifying witnesses and bringing them to police stations for the investigations to proceed.

- Appreciating the physical, mental or socio-economic challenges faced by survivors in reporting ERSV cases within a period during which forensic evidence may be collected.

- Being cognisant that in situations of unrest, sexual violence may have similar patterns. IAU seemed to lack appreciation that sexual violence during situations of unrest may manifest in similar patterns: some of their investigators questioned the credibility of survivors’ accounts because of these similarities.

Interviewees from the three investigative agencies noted that unaddressed mental health concerns and psychological welfare of investigators working in the investigating agencies affects their ability and capacity to conduct prompt and thorough investigations into ERSV. It is compounded by inadequate training on how to handle the effects of ERSV, and absence of mandatory and regular debriefings. Police interviewees added that the poor socio-economic, living and working conditions of police officers affects their ability, willingness and commitment to undertake prompt, independent, transparent and thorough investigations that are capable of uncovering the facts of what happened, and identifying and punishing those responsible.

Absence of effective systems, procedures, measures and safeguards to facilitate investigative agencies to undertake effective investigations into police-perpetrated ERSV

Respondents from investigative agencies indicated they contend with barriers in conducting effective investigations of police-perpetrated ERSV due to:

- Absence of effective systems and procedures to handle cases of police officers who fail to or are unwilling to investigate their colleagues owing to comradery amongst police officers.

- Lack of transparency and information on the deployment of police officers, including reinforcements, during the elections, which hampered the identification of alleged direct police perpetrators and the conduct of investigations. The massive deployment of security officers prior to and during the 2017 election period was largely executed without information being provided to communities,[64] therefore posing challenges in pursuing accountability for police-perpetrated ERSV. Survivors from Kisumu, Vihiga and Nairobi Counties observed that ‘there was a change of guard of police officers who had been working in our areas within a short period before the general elections. New police officers who were not known by communities were brought in.’ In stark positive contrast, it was observed that the police commanders in Homabay County held community dialogues and introduced newly deployed officers to the communities.

Failure to address existing structural resource and capacity gaps to conduct prompt, thorough and effective investigations of sexual violence during non-election years

Lack of adequate financial, human and physical resources to investigative agencies to facilitate the conduct of prompt, thorough and effective investigations of sexual violence during non-elections exacerbated the obstacles of conducting investigations of ERSV. These include:

- Lack of gender desks or specialised units to handle cases of sexual violence at all police stations. Where available, the gender desks or offices are not always or regularly staffed with police officers who have received specialised training on handling sexual violence cases, including how to undertake effective investigations of ERSV cases.

- Unavailability of Occurrence Books (OBs), a mandatory tool used by the police to record all incidents of crimes, and mandatory P3 forms used by police officers to request medical examinations of survivors and perpetrators (if available) so as to document medical evidence. Survivors reported being asked for payment to make photocopies of the P3 form, or to download the form from the internet themselves.

- Lack of knowledge amongst police officers that medical PRC forms can be used in lieu of the police P3 form. The NPS Service Standing Order stipulates that the use of PRC forms suffices in sexual violence cases, but the Police Manual does not reflect this.

- Absence of designated physical spaces to safeguard the privacy and dignity of survivors of ERSV filing reports at police stations.

- Lack of facilities and infrastructure for proper evidence storage, leading to the loss or adulteration of evidence in support of reported ERSV cases. IPOA, IAU and the Government Chemist reported cases of improper management of forensic evidence collected by police officers in ERSV cases due to improper storage and handling of exhibits.

- Lack of support within police stations to provide financial assistance to ERSV survivors to travel to and attend health institutions for the documentation of sexual violence or return for follow up.

- Negative attitudes, prejudices and stereotypes on ERSV by police officers. Police officers indicated that sexual violence is not treated as a ‘top-priority crime’, as opposed to crimes such as murder.

Weak coordination and cooperation among investigative agencies

The State is obliged to encourage cooperation and coordination amongst all levels and branches of the justice system, including investigative agencies, in order to improve access to justice for victims of ERSV.[65] Coordination and cooperation across investigative agencies were less than optimal due to misconceptions and a lack of understanding of each agency’s mandate to conduct investigations. Some police officers perceived IPOA as ‘against the Police’ and felt that their investigations were not impartial. This affects the officers’ will to collaborate with IPOA on investigations, including investigations of ERSV.

Further, there was no mechanism to formalise effective coordination between investigative agencies and oversight bodies with investigative mandates,[66] such as KNCHR, which has a good reach within communities, is a crucial source of information and is mandated to ‘refer and report cases to relevant agencies for further follow-up’.

Weak linkages and inadequate cooperation with organisations working with survivors

The State must work together with survivors of sexual violence and organisations that work to support survivors, in order to properly consider their views and expertise, as well as access relevant information to improve access to justice for survivors.[67]

The study found a widespread perception within the Police, including the IAU, that NGOs are ‘against the NPS’, hence unwilling to cooperate with the Police. The three investigative agencies expressed frustration that non-state actors, such as civil society organisations and humanitarian agencies, were unwilling to share information which would assist in the conduct of their investigations, but did not appreciate the application of principles of confidentiality and prior informed consent of ERSV survivors.

Cooperation between investigative agencies, especially Police, and survivors and communities is poor due to mistrust. Survivors indicated that they do not trust the Police and stated they would be unwilling to engage with the IAU, perceived as a branch of the Police as opposed to being an oversight body, and with the IPOA, which they believe to be staffed with police officers. Lack of transparency with local communities regarding the deployment of police officers during the 2017 election period also strained relations between the Police and communities, fuelling mistrust and affecting willingness to cooperate with investigators following up on cases that resulted from the violence.

Need for strengthened prosecution capacity

The State is obliged to prosecute cases of ERSV, to ensure accountability for violations and abuses, and provide effective remedies. The study found that there was insufficient capacity and resources within ODPP and the Judiciary, in particular:

- Limited specialised technical capacity within ODPP, including availability of mandatory specialised training on how to prosecute and undertake prosecution-led investigations on ERSV;

- Inadequate human and financial resources within ODPP to prosecute ERSV. There is only one specialised SGBV unit in Nairobi, with none at the county level;

- Lack of a specialised division within the Judiciary to hear and determine cases on sexual violence, including ERSV;

- Lack of specialised mandatory capacity building on ERSV for the Judiciary;

- Inordinate delays of more than 8 years in the Judiciary completing hearings and delivering judgements in constitutional cases filed by ERSV survivors from 2007/2008,[68] seeking accountability for violations and reparations for harm suffered.

Lack of effective data collection, monitoring, evaluation and oversight to track progress of cases through the criminal justice system

The State is obliged to establish a system to regularly collect, analyse and publish statistical data on SGBV, including ERSV. This should include data on the number of complaints received; the rates of dismissal and withdrawal of complaints; prosecution and conviction rates; time taken for disposal of cases; sentences imposed; and compensation/reparations provided to survivors. The analysis of data collected should enable the identification of protection failures (including in investigations and prosecutions) and improve and further develop prevention and response measures to ERSV.[69] This obligation requires that all State agencies operating within justice process establish well-conceived, operated and coordinated data collection systems.

The study established that although NPS, IPOA, ODPP, NGEC and the Judiciary collect data on sexual violence cases, this is inadequate because:

- The various data collection systems are not harmonised nor linked, and do not collect uniform data. Therefore, Kenya has no system in place to track the progress of sexual violence cases throughout the criminal justice system from the point of entry into the system to the conclusion.

- The data collection systems of NPS, IPOA, ODPP and Judiciary do not disaggregate data on type of ERSV cases and perpetrators.

- The Judiciary’s data on sexual violence is recorded in its ‘Sexual Offences Case Register’ that only documents cases that led to conviction, as opposed to all cases which are heard and determined by the courts of law.

- Data collected by the ODPP, IPOA and IAU is not regularly published or readily available for review by external parties, including survivors, civil society and other Government offices, so as to inform planning for prevention and response initiatives prior to elections.

- Although IPOA publishes statistics on sexual violence cases received, disaggregated data on locations and perpetrators is only available upon written request.

- State actors in the criminal justice system are supposed to provide data on SGBV cases to NGEC’s centralised, integrated data collection and information management system, the Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Information System (SGBVIS).[70] However the system is not up to date because criminal justice actors provide irregular and incomplete updates.

State Obligations to Provide Remedies and Reparations

As part of the obligation to provide access to justice, including adequate, effective, prompt and appropriate redress and remedies, the State is under an obligation to provide reparations for SGBV, including when such acts constitute international crimes.[71] This relates to SGBV when committed by state actors, as well as omissions and failure to prevent, protect and provide access to justice on the part of public authorities. In the absence of reparations, the obligation to provide an appropriate remedy is not discharged.[72] Under international human rights law and standards, the State must ensure that reparations are adequate, proportional to the gravity of the human rights violations and harm suffered, comprehensive, holistic, effective, timely, promptly attributed, transformative, complementary, inclusive and participatory.[73]

The study established that while Kenya has initiated efforts to provide reparations, the following gaps remain glaring:

- The Government is yet to specifically acknowledge the violations suffered by survivors, the State responsibility in relation to these violations, and the burden and plight that survivors are currently facing. Government has not initiated yet a process of consultation with survivors in relation to reparations.

- The draft Public Finance Management (Reparations for Historical Injustices Fund) Regulations 2017 is yet to be adopted, and there are inadequate consultations with survivors and civil society organisations to guide the operationalization of the Restorative Justice Fund. In March 2015, President Uhuru Kenyatta had directed Treasury to set up a KES 10 Billion Restorative Justice Fund (close to 10 Million US dollars) to be utilised for restorative justice processes over a period of three years.[74] The Fund was to be used to ‘provide a measure of relief’ to victims of gross human rights violations, including survivors of ERSV to repair harm and losses suffered but has never been operationalised. In April 2019, President Kenyatta reaffirmed his commitment to the Restorative Justice Fund but stated that the funds would go towards “establishing symbols of hope across the country through the construction of heritage sites and community information centres.”[75] This declaration excludes important aspects of comprehensive and effective individual reparations for survivors of ERSV, including survivors that bore children of rape and male survivors.

- The Government gazetted the TJRC report, but excluded Volumes IIA and IIC, which provide lists and details of incidents of sexual violence as gross human rights violations. Parliament has not debated and adopted the TJRC report in full, in particular the section dealing with sexual violence.

- The Government has failed to respond to the urgent and continuing needs and priorities of ERSV survivors. Interviewed ERSV survivors identified the following pressing measures for reparations: comprehensive medical care (e.g. for eye injuries due to tear gas used in Vihiga county in 2017); psychosocial support, including for families and communities; support for children born of rape; education for child ERSV survivors whose education were disrupted (e.g. in Bungoma county); compensation for economic losses; and assistance to participate in justice processes.

The comprehensive and diverse forms of reparations to survivors of ERSV include: restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition[76]. Compensation should be appropriate and proportionate to the gravity of the violation and the circumstances of each case, recognizing wide-ranging harm faced by survivors, such as: physical or mental harm; lost opportunities, including employment, education and social benefits; material damages and loss of earnings; moral damage; and, costs required for legal or expert assistance, medicine and medical services, and psychological and social services. Rehabilitation, on the other hand, could be through the provision of adequate, available, accessible, acceptable and quality legal, social and health services, including medical, sexual, reproductive and mental health services for the complete recovery of ERSV victims.

Measures of satisfaction may include public and official acknowledgement of the violations and of State responsibility in relation to the acts and omissions, as well as measures to fulfil victims’ right to truth, including in relation to ERSV, official public apologies, symbolic measures, such as commemorations and tributes to survivors of ERSV, as well as measures to bringing to justice perpetrators of ERSV, as well as guarantees of non-recurrence, such as legal and institutional reforms, as well as educational, societal and cultural interventions, among others.

III. Conclusion

Sexual violence surrounding elections has remained a recurrent feature in Kenya’s electoral cycles, which compounds the existing persistent crisis in society. Concrete actions are needed to ensure accountability, address the grievances and meet the rights needs of survivors, and put in place effective preventive measures well ahead of the next elections in 2022. Although the Government of Kenya has made laudable steps towards the establishment of legislative, institutional and other measures aimed at addressing sexual violence, there remain numerous gaps and barriers to effective prevention of and response to ERSV that need to be urgently addressed so that ERSV does not recur in future elections.