Press release available in English and Ukrainian.

Executive Summary

This case study expands on existing documentation of Russia’s widespread and systematic attacks on Ukraine’s health care system. It explores ways in which Russia has sought to systematically target health care as an apparent means of degrading resistance and, in Ukraine’s occupied territories, as a means of enforcing control over the civilian population, including by limiting and conditioning access to health care through a range of coercive practices. These practices include: (1) Russian forces misusing civilian health facilities for nonmedical purposes; (2) requiring forced changes of nationality as a precondition for gaining access to health care (otherwise known as “passportization”); and (3) threatening and harassing health care professionals as a way to further limit care and assert control over Ukraine’s health care system.

Based on a joint dataset, the study details a range of reported incidents that collectively suggest an apparent pattern of illegal attacks on health by Russia that both limit and violate the right to health of Ukrainian civilians. These attacks are violations of both international humanitarian law (IHL) and international human rights law. They also threaten the integrity of Ukraine’s health care system, which, while resilient, faces ongoing challenges following Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022.

The destructive impact of a compromised health care system threatens to impose long-lasting and severe hardship on Ukraine’s people. The Russian Federation must end its aggression, cease its violations, and return the administration of Ukraine’s health care system in the occupied territories back to the Ukrainian government.

The destructive impact of a compromised health care system threatens to impose long-lasting and severe hardship on Ukraine’s people. Russia must end its war of aggression and return the administration of Ukraine’s health care system in the occupied territories back to the Ukrainian government. At the same time, there remains a pressing need to ensure accountability for violations of IHL with respect to health care, for which there has been almost complete impunity in both Ukraine and globally. All investigative and prosecutorial bodies with relevant jurisdiction – including the International Criminal Court’s Office of the Prosecutor, the Prosecutor General of Ukraine, the UN’s Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine, and other national prosecutors – must prioritize the investigation of attacks on health care as both war crimes and crimes against humanity, including the range of violations discussed herein.

Introduction

Since the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, there have been a staggering 1,154 attacks[1] on the country’s health care facilities, workers, and medical infrastructure, amounting to approximately two attacks per day.[2] In 2022 alone, Ukraine’s health care system constituted more than one-third of all reported health-related attacks globally.[3] Hospitals and clinics have been damaged or destroyed in over 500 incidents and at least 40 facilities were damaged more than once since February 2022.[4] The violence has not been limited to striking hospitals and clinics. It includes the shelling of ambulances, the looting of pharmacies, and acts of violence – killing, arbitrary detention, and torture – against health care personnel.[5]

The report “Destruction and Devastation: One Year of Russia’s Assault on Ukraine’s Health Care System” – published in February 2023 by eyeWitness to Atrocities, Insecurity Insight, the Media Initiative for Human Rights (MIHR), Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), and the Ukrainian Healthcare Center (UHC) – established a reasonable basis to believe that attacks on Ukraine’s health care system constitute war crimes and potentially crimes against humanity as well.[6] Drawing on 10 case studies and a joint dataset of attacks, it showed how Russian forces appear to be deliberately and indiscriminately targeting Ukraine’s health care system as part of a broader attack on its civilian population and infrastructure.

There remains a pressing need to ensure accountability for violations of International Humanitarian Law with respect to health care, for which there has been almost complete impunity in both Ukraine and globally.

The scale of such attacks underscores their destabilizing impact on Ukraine’s civilian population, from limited access to vital medicines to reduced access to critical health care services. While Ukraine’s health care system has shown resilience, it still faces enormous public health challenges, including fewer routine vaccinations, a rise in heart attacks and strokes, increased hospitalizations for infectious diseases in regions hosting many internally displaced persons, and growing financial barriers to obtaining necessary medicines.[7] The primary health care system is in a state of deep crisis, struggling to meet the basic health care needs of the population.[8] The Russian invasion has also led to a significant increase in mental health issues and stress for all segments of the Ukrainian population.[9] Notably, there is a particular need for systemic rehabilitation services for Ukrainian veterans and military service members.[10] Rebuilding facilities also demands substantial investments, with an estimated cost of $16.4 billion over the next decade for full reconstruction and recovery.[11]

At the same time, ongoing attacks on health comprise more than physical acts of destruction. They also include other, less visible attacks often inflicted upon civilian populations and the community of health care professionals who labor amid conflict. In particular, in the Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine,[12] several patterns have emerged that profoundly affect civilians’ access to crucial health care services and medications as well as the health and safety of Ukrainian health care professionals.

This case study explores ways in which Russia has sought to systematically target health care as an apparent means of degrading resistance and, in Ukraine’s occupied territory, as a means of enforcing control over the civilian population, including through access to health care. It demonstrates what is happening to patients, providers, and the health system in these regions, where access remains exceedingly rare.

Covering the period from the start of the full-scale invasion in February 2022 to September 2023, the study explores these phenomena in the following ways:

- The misuse of health facilities for nonmedical purposes: The use of Ukrainian hospitals by Russian forces for military purposes is a violation of their protected status under international law. It has also exposed patients and health care workers to a greater risk of violence. The repurposing of facilities for military medical care has severely limited civilian access to health care. The seizure of health infrastructure, including medical equipment, which often occurs during (or immediately after) occupation, further disrupts the provision of health care and likely violates the law of occupation as well.

- Forced change of nationality (“passportization”) of population through medical services: The practice of “passportization,” whereby civilian access to health care is conditioned upon a forced change of nationality, is increasingly used in Ukrainian territories currently under Russian occupation. This not only imposes an external identity on Ukrainians – a forced change of nationality – but also restricts their ability to access health care and other medical support.

- Threatening and harassing health care personnel: Health care workers in Ukraine’s occupied territories are laboring under immense duress. Local medical personnel face significant pressure as they are forced to work in occupied hospitals, compelled to operate under Russian law, and to deny care to Ukrainian citizens resisting “passportization,” pushed to undergo retraining in Russia, or even replaced by Russian doctors. The persistent risk of detention and other punitive measures creates a hostile and perilous environment for health care professionals, inflicting a range of physical, mental, and moral injuries.

Based on the dataset maintained by our organizations, there have been at least:

- 16 reported incidents where a health facility was repurposed for nonmedical purposes, including as a military base, to store weapons, or to otherwise plan military action;

- 34 reported incidents where civilian patients were forcefully evicted from a health facility or denied access to health care, and the facility was then reportedly repurposed for the use of wounded soldiers;

- 23 reported incidents where medical supplies were requisitioned by Russian forces;

- 15 reported incidents of “passportization” – denying medical care to people without a Russian passport or coercing civilians into obtaining one to access health care; and

- 68 health care workers who were detained in 17 separate reported incidents.[13]

Collectively, these incidents suggest an apparent pattern of conduct by Russia that both limits and violates civilians’ right to health and imperils their ability to access essential health services. They undermine not only the efforts of those interested in upholding care amidst conflict but serve to expand Russia’s coercion of and control over Ukraine’s civilian population.

In detailing these incidents, the case study also identifies some of their potential implications under international law, with reference both to international humanitarian law (IHL) and human rights law. Its conclusions underscore a grim reality but affirm a critical obligation in the context of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine: violations of the protected status of health care and health personnel must be prioritized for investigation and prosecution.

Methodology

The information cited in this study is based on reported incidents. It remains exceedingly difficult to access Ukraine’s occupied territories and data on health attacks – as well as their impact – remains limited and incomplete. The ability to physically document and verify attacks on the ground remains out of reach, constraining this study’s scope. To that end, the cited incidents should be understood as examples and not as representing a complete count of all incidents across Russian-occupied territories. Indeed, the examples are almost certainly an undercount.

This study has sought data from multiple sources, including audiovisual evidence, open-source research, and interviews with Ukrainian health care workers interviewed by MIHR, PHR, and UHC. It also draws upon reported incidents collected by Insecurity Insight from open sources and data provided by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Incident data was collected through collaborative efforts among the partner organizations as well as from UHC.[14] The dataset brings together individual incidents from a range of sources, including open-source research, the eyeWitness app, witness and victim accounts, site visits undertaken by UHC and PHR[15], and networks from organizations working on the ground. It has been compiled using an incident-based approach to evidence collection, where individual incidents are collected, verified, and combined to allow for an analysis of patterns of violence over time and in different locations.[16] All incidents were then reviewed, verified based on a range of criteria within the limits of research partners’ technical and resource capacity, and assigned an incident number. The dataset is regularly updated on a digital, interactive map at www.attacksonhealthukraine.org.

This study’s methodology was approved by PHR’s Ethics Review Board (ERB) to ensure compliance with U.S. requirements for human subject research.[17] All interviews were conducted using a range of security precautions and protections. The incident data collection follows Insecurity Insight’s ethical guidelines on documenting and reporting incidents of attacks on health care. Certain incident data collected by other organizations like the WHO, however, remains unavailable for comprehensive analysis.[18]

As part of the methodology for this report, the research team submitted an official request for information to Ukraine’s Ministry of Health to confirm the number of health facilities in Ukraine’s occupied territories, which is discussed below.[19] It also submitted an information request for more detail on events reported by the WHO; however, at the time of publication, no response had been received.

For the purpose of this study, Russian-occupied territories were defined within the framework established by the Ministry of Reintegration of the Temporarily Occupied Territories of Ukraine, including territories that were occupied and have since been liberated by the Ukrainian forces and territories that are still under occupation.[20] A case-by-case decision as to whether an incident occurred in an occupied territory was taken based on the best available information at the time.

Applicable Law

Under IHL, a “territory is considered occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of the hostile army. The occupation extends only to the territory where such authority has been established and can be exercised.”[21] This case study references several towns, cities, and oblasts that are either currently, or were for a certain period, under the effective control of Russia. With regard to Donetska, Khersonska, Luhanska, and Zaporizka oblasts as well as Crimea, the study accepts the proposition that, consistent with international consensus,[22] these areas are only temporarily occupied and continue to remain part of Ukraine.[23] Given this context, IHL, and more specifically a subset of rules known as “occupation law,”[24] as well as human rights law, form the applicable legal framework for this study.[25] As supported by a wealth of international jurisprudence, human rights law does not cease to apply in situations of armed conflict,[26] and binds states even when they operate outside their territory, and “particularly in occupied territories.”[27]

| Serious violations of IHL may constitute war crimes under international criminal law (ICL).[28] Specifically, the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I establish that certain violations of IHL are to be considered “grave breaches” and must be prosecuted by state parties.[29] Individual criminal responsibility for other serious violations of IHL is established by customary international law and by international criminal law treaties, such as the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Such violations, together with grave breaches, constitute war crimes. Some of these violations may also constitute crimes against humanity if they are committed “as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack.”[30] |

Occupation law. The rules included within this specific branch of IHL rest on the fundamental premise that the Occupying Power – here, Russia – has not acquired sovereignty over the occupied territory and that the occupation is merely temporary. Existing laws and institutions should thus be respected and maintained as far as possible in order to preserve the status quo ante in the occupied territories.[31] In a balancing exercise between the Occupying Power’s purported military interests and those of the local population, occupation law fundamentally aims “to ensure the protection and welfare of the civilians living in occupied territories.”[32] In this sense, the Occupying Power must leave any local legislation in force provided that it does not constitute a threat to security or an obstacle to the application of the law of occupation.[33]

Right to health. Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (to which both Ukraine and Russia are party) “recognize[s] the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.”[34] States have an obligation to maintain a functioning health care system in all circumstances, including during armed conflicts and in occupied territories. With regard to the situation in Ukraine’s occupied territories, IHL already imposes certain positive obligations upon the Occupying Power in relation to health.[35] The human rights framework goes further by clarifying that states have an obligation to take all necessary steps and use their resources to the maximum extent available to maintain, at the very least, essential primary health care, ensuring access to health facilities, goods, and services, as well as to the minimum essential amount of food, adequate supply of safe and potable water, basic shelter, housing, and sanitation. They should also provide essential drugs, while respecting the principles of nondiscrimination and equitable access.[36]

Health Care Under Occupation: Repurposing of Health Facilities and Seizing of Health Supplies

| Applicable Law Medical units are afforded specific, enhanced protection[37] under IHL due to “their primary importance during armed conflicts, both to maintain public health and to care for the wounded and sick caused by the armed conflict” and regardless of whether they are military or civilian.[38] They shall be respected and protected at all times by the parties to an armed conflict.[39] In occupied territories, the Occupying Power has the duty, to the fullest extent of the means available to it and in cooperation with national and local authorities, to ensure and maintain medical and hospital establishments, services, as well as public health and hygiene.[40] Additionally, it is also the responsibility of the Occupying Power to provide the necessary medical supplies for the population of the occupied territory, including by importing it into the area if the supplies in the region in question are inadequate.[41] |

According to the most recent information provided to the research team by Ukraine’s Ministry of Health, as of October 2023, there were or are 364 health facilities registered on territories temporarily occupied by Russia,[42] out of a total of 3,555 health facilities in Ukraine.[43]

In 2023, the Ukrainian government has financially supported (at a cost totaling $48.5 million) 143 health facilities in the occupied territories through the National Health Service of Ukraine (NHSU),[44] with the declared intention of “[e]nsuring the preservation of human resources to provide medical care to the population in the temporarily occupied territory.”[45] The payment mechanism to support these facilities involves cross-referencing employee information from multiple sources, including official authorities like the Security Service of Ukraine, to determine access to health care funds, disconnecting health care facilities from the electronic system, and halting payments if irregularities are found.[46]

Based on the number of hospitals receiving financial support from Kyiv, it is estimated that up to 60 percent – or 221 health facilities – in the occupied territories remain disconnected from the Ukrainian health system. According to the International Organization for Migration’s GPS reporting, since December 2022, 28 percent of Ukrainians residing under current Russian occupation have insufficient access to medical services and medicines.[47]

Patients thus face the risk of significantly reduced access to health care. They may be less likely to seek access to care under occupation out of fear for their safety, particularly where health facilities have been repurposed for nonmedical purposes. Logistical hurdles – such as the inability to access transportation to travel to an available civilian hospital, or financial difficulties, including the inability to cover expenses for services from private health care facilities or providers – can further restrict patients’ access to medical services. Collectively, these obstacles can lead to an increased risk of health complications. Although NHSU receives reports from the contracted hospitals, the real picture of the health care situation in areas currently under Russian occupation is not fully known.

Repurposing Health Facilities for Nonmedical Purposes

Applicable Law

According to the ICRC Commentary to Article 57 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, civilian hospitals in temporarily occupied areas can in no circumstances be requisitioned for “non-medical purposes.”[48] This interpretation of the provision on hospital requisitions is further supported by a combined reading of a number of IHL rules, such as the provisions requiring that medical units are not, as far as possible, located in the vicinity of military objectives,[49] that they may under no circumstances be used in an attempt to shield military objectives from attack,[50] and that protected objects lose their protection when used, outside their humanitarian function, to commit acts harmful to the enemy.[51]

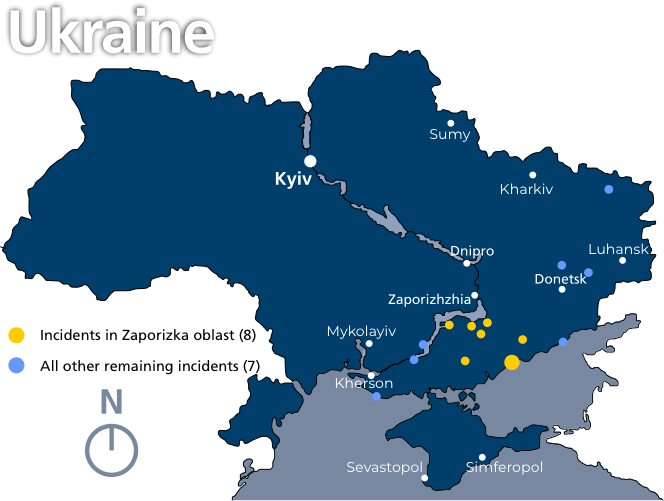

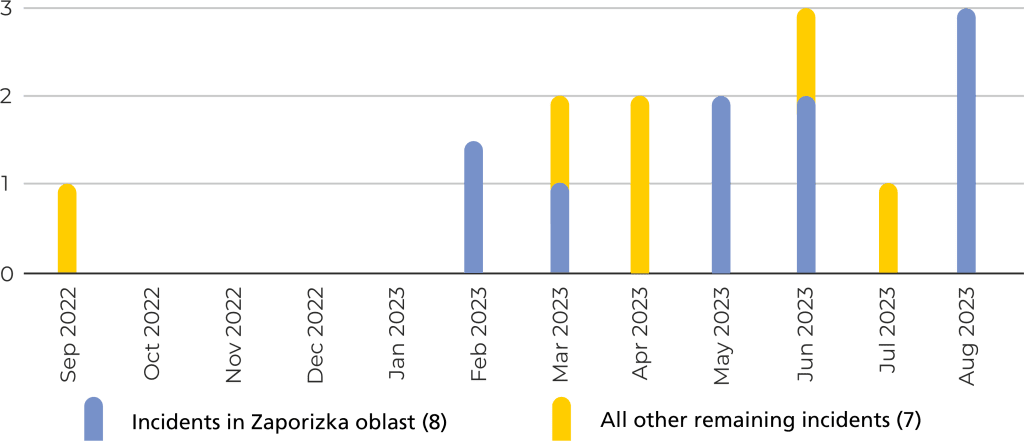

Based on the research team’s dataset, 16 health facilities in five of Ukraine’s oblasts were reportedly repurposed into military bases or for other nonmedical purposes. In all 16 cases, the health facility was fully functioning at the time of their repurposing. Most of these incidents were reported in Zaporizka oblast, where seven such cases were recorded. Five incidents took place during the first three months of the full-scale invasion, with cases being more frequently reported after November 2022. For instance:

- One former children’s hospital used as a COVID-19 hospital in Zaporizka oblast was reportedly repurposed into a military base in November 2022 (incident 35830).[52]

- A women’s hospital in Luhanska oblast was reportedly repurposed into a military base in January 2023 (incident 36931).[53] In March 2022, a psychoneurological boarding facility in Bucha, Kyiv was seized by Russian forces who fired artillery from its premises (incident 33352).[54]

- In March 2023, a hospital in Luhanska oblast was reportedly turned into barracks for Russian soldiers (incident 37605).[55]

- In July 2023, a hospital in Luhanska oblast was reportedly occupied by the paramilitary Chechen unit Special Rapid Response Unit (SOBR) “Akhmat” under the instruction of Russian authorities (incident 39938).[56]

- The repurposing of health facilities was also accompanied by other takeovers. For example, in Osypenko village, Zaporizka oblast, Russian military forces reportedly occupied the local hospital and civilian homes (incident 40276).[57]

| Dr. Oksana Kyrsanova, an anesthesiologist at the Regional Intensive Care Hospital in the city of Mariupol, spoke to MIHR researchers about the occupation of the hospital by Russian forces on March 12, 2022[58], describing how doctors provided care during the occupation, and the conditions under which staff worked (incident 36432).[59] “They made our hospital their headquarters. They had a rotation, first there were some, then others came. They occupied the entire building, completely surrounded and controlled the hospital, all entrances, exits, and stairs. They were on the roof of our hospital. We had a very big building, and they had a view of everything.” “And indeed, we saw it all, they [Russian forces] set up their equipment and shot from the hospital buildings. Military equipment was placed around the perimeter of the hospital. Armored personnel carriers stood on all sides of the hospital. There were snipers on the roof and top floors. There were probably four soldiers on each floor. There were a lot downstairs, probably 10 [soldiers] and three armored personnel carriers. The soldiers would rotate; the armored personnel carriers hid, for example, between two houses right in front of the windows.” |

Other incidents appear to have also involved repurposing for military use, but no details of how they were so used were provided. For example, in March 2022, a hospital in Slavutych city, Kyivska oblast, was taken over by Russian forces during their invasion of the city (incident 31988).[60] And in November 2022, an infectious diseases hospital in Melitopol city, Zaporizka oblast, was occupied by the Russian military (incident 35831).[61]

There have also been nonspecific reports about the use of health care facilities by the Ukrainian forces.[62] However, our organizations have not been able to independently verify such misuse.

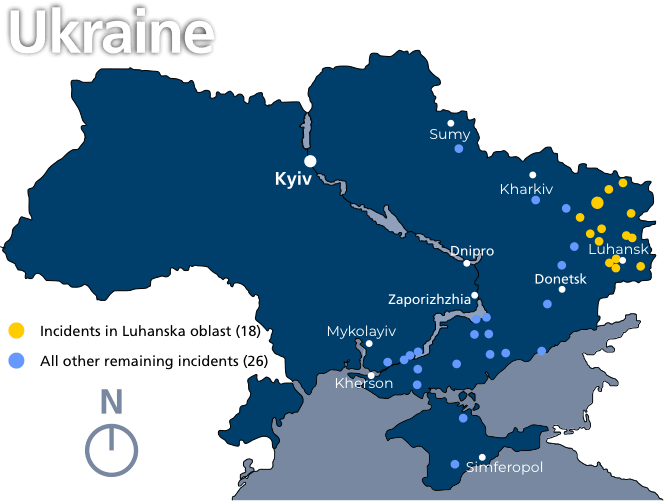

Reported locations of health facilities in Ukraine repurposed into military bases by Russian forces, February 2022 – August 2023

On at least 16 occasions, fully functioning health facilities were taken over by Russian forces and turned into military bases. Most of these incidents were documented in Zaporizka oblast.

Military use of protected infrastructure is a violation of IHL, as it infringes the protected status of such sites and personnel. In addition to the risk that such “dual purpose” use of hospitals and health facilities poses to the civilian population – exposing them to greater risk of attack by combatant forces – the occupation of civilian hospitals also strains health care resources.

| Olena Yuzvak, head of the Primary Care Center in Hostomel, Kyivska oblast, spoke to PHR about the occupation of the clinic (incident 41998)[63] from February through March 2022:[64] “In the building of this primary clinic was the base of the Russian military, and in the basement of this building were children, civilians who were not even allowed to go outside and cook some food, because it was dangerous, no one allowed them to do so. And the people who tried to leave on their own because they were losing it and wanted to leave this hell, […] their cars were shot, they were civilians.” Olena’s husband and son, both civilians, were taken prisoner by Russian forces. Her husband, who was shot when Russian soldiers entered their private house, has since been released in a prisoner exchange, but her son, Dmytro, remains in captivity. |

Repurposing health facilities as military bases violates IHL and may constitute war crimes. The incidents narrated by doctors from Mariupol and Hostomel, in particular, raise concerns that merit further investigation.

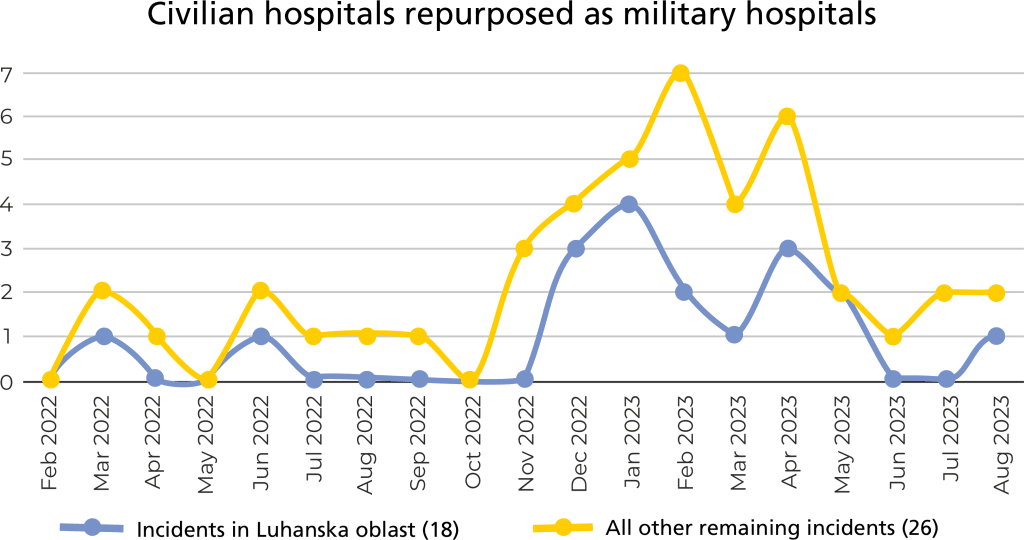

Civilian hospitals repurposed as military hospitals

Applicable Law

Civilian hospitals – whether public or privately owned – may only be requisitioned in cases of urgent necessity for the care of military wounded and sick and on a temporary basis, provided that suitable arrangements are made in due time for the care and treatment of patients and for the needs of the civilian population as a whole for hospital accommodation.[65] It follows that the Occupying Power must not do so if its own medical establishments can cope with the wounded and sick of the army.[66] Additionally, hospitals need to be returned to their normal use “as soon as the state of necessity ceases to exist, that is as soon as the medical services of the occupation forces are able to cope with the needs of their wounded and sick.”[67]

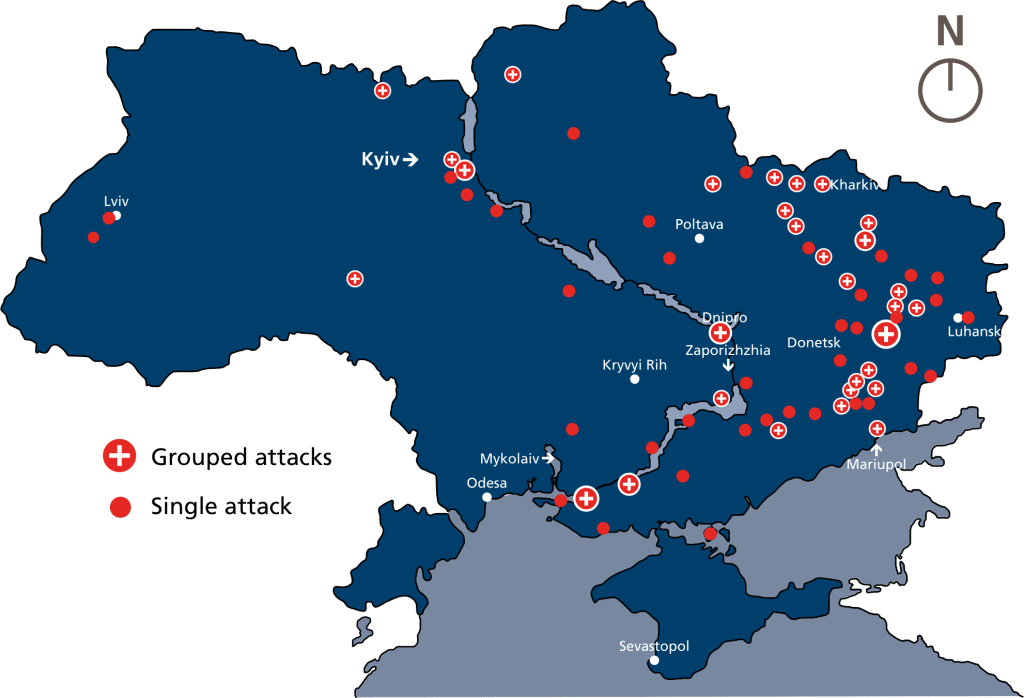

In 44 reported incidents, health facilities in seven of Ukraine’s oblasts were reportedly repurposed for the use of Russian soldiers. These takeovers of civilian facilities for military medical use were particularly frequent in February 2023 and the number of reported new takeovers increased between February and April 2023. In all 44 cases, the health facility was fully functioning at the time that it was repurposed from civilian use for the use of soldiers.

Most of these incidents were documented in Luhanska oblast, where 18 cases were recorded, with most taking place between December 2022 and May 2023. Incidents were also common in Zaporizka oblast with 10 and Kherson with seven. Of note:

- Six women’s hospitals were reportedly repurposed for the use of soldiers, five of which were in Luhansk and one in Zaporizhzhia.

- Three children’s hospitals were reportedly repurposed for the use of soldiers: two in Zaporizhzhia and one each in Kharkiv.

In 34 of the 44 incidents, it was specifically reported that civilians were forcibly evicted from a health facility or denied access to health care, and the facility was then repurposed for the exclusive use of wounded soldiers. For example:

- In November 2022, Russian forces reportedly expelled patients from an emergency hospital in Melitopol, Zaporizka oblast (incident 35779).[68]

- In March 2023, a maternity hospital in Luhansk was allegedly taken over and turned into a military hospital by Russian forces. Women in labor were transferred to the two remaining maternity hospitals in the city (incident 37751).[69]

- Later in May, Russian forces reportedly handed the hospital over to the Russian-government–linked Wagner Group private military for the use of treating their wounded soldiers (incident 39079).[70]

Reported locations of health facilities in Ukraine repurposed for the use of wounded Russian soldiers, February 2022 – August 2023

Fully functioning health facilities were repurposed from civilian use to soldiers by Russian forces at least 44 times. A great number of incidents was documented in Luhanska oblast between December 2022 and May 2023

Based on available information, it is unclear whether these incidents satisfied the “urgent necessity” threshold of the Fourth Geneva Convention, nor is it clear if the health needs of specific patients, and access to health care for the civilian population as a whole, were adequately taken into account in these incidents. However, the way in which the use of beds and infrastructure were reportedly requested and taken over raises significant concerns about the equitable provision of care to all wounded and sick people.

The extent to which civilians were cut off from care as a result of requisitioning underscores the harmful health impacts of the continued occupation. Indeed, the reported medical needs within areas currently occupied by Russian forces are often so great that local health care capacities cannot cope with both Russian military and civilian populations. In Luhansk city, for instance, as well as in towns of the oblast, hospitals reportedly operate at full capacity. One person, whose father had a broken hip but was turned away at the hospital, reported that doctors “received an instruction from Luhansk to give hospital beds to wounded soldiers, and to send civilians back if they do not have a heart attack.”[71] Similarly, in Dovzhansk, a maternity ward was reportedly vacated to accommodate wounded Russian soldiers instead (incident 41997).[72]

The redirection of medical care to wounded combatants may have implications for civilians in the occupied territories. For instance, more than 450 wounded Russian military personnel were reportedly being treated in the city hospital of the occupied city of Dniprorudne, Zaporizka oblast, likely impacting the availability of medical services for civilians (incident 37004).[73] A similar situation is observed in Donetsk, where routine surgeries for civilian patients are reportedly being canceled (incident 42120),[74] making it increasingly difficult for the civilian population to access medical services across the region (incident 38618).[75] Additionally, in the occupied part of Khersonska oblast in January 2023, particularly in Kakhovka, a tuberculosis dispensary was transformed into a military hospital to treat Russian soldiers (incident 37667).[76]

In Crimea, increasingly more hospitals are reportedly being reoriented into military hospitals, restricting the civilian population’s ability to receive medical services.[77] The new Semashko Medical Center in Simferopol, with the capacity to treat 650 patients, was turned over to the Russian military (incident 39428).[78]

The conversion of civilian hospitals located in former or current occupied areas of Ukraine into military hospitals – such as the ones reported in Donetska, Khersonska, Luhanska, and Zaporizka oblasts – suggests a worrisome pattern by Russian forces. Further investigation is required, however, to confirm whether there was an “urgent necessity” in each instance and, if so, whether hospitals were restored to their normal use as soon as that urgency ceased to exist. There has also been no documented effort to expand the capacity of care for soldiers and civilians alike.

Seizure of Medical Supplies and other Forms of Appropriation

Applicable Law

Specific rules regulate the Occupying Power’s ability to requisition articles and medical supplies available in the occupied territory. According to the IHL framework, such requisitions are only allowed for use by occupying forces and administration personnel,[79] provided that the requirements of the civilian population have been taken into account and that fair value is paid in return.[80] Requisitioning equipment and medical supplies on an excessive scale would amount to the grave breach of the norm prohibiting appropriation of property.[81] Other forms of appropriation are also prohibited, namely pillaging and seizing the enemy’s property. [82]

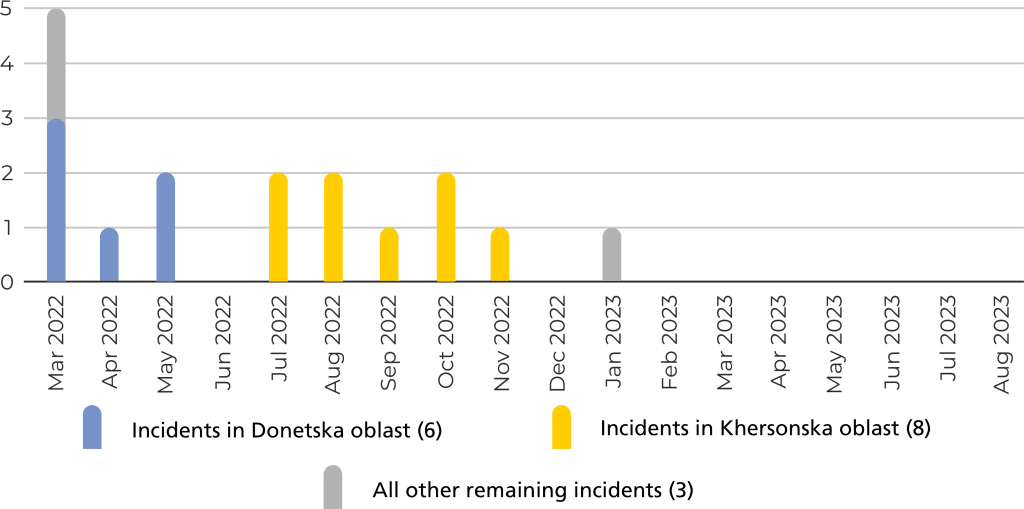

The research team identified 23 reported incidents, in six of Ukraine’s oblasts, where Russian forces requisitioned medical supplies and equipment needed for the running of the health system, including computers, digital and medical equipment, hospital furniture, medicine and blood supplies, and, in one case, building supplies from a hospital under construction. While the details about the specific circumstances are not always clear, there is indication that requisitioning occurred in the context of armed threats, coercion, or harassment.

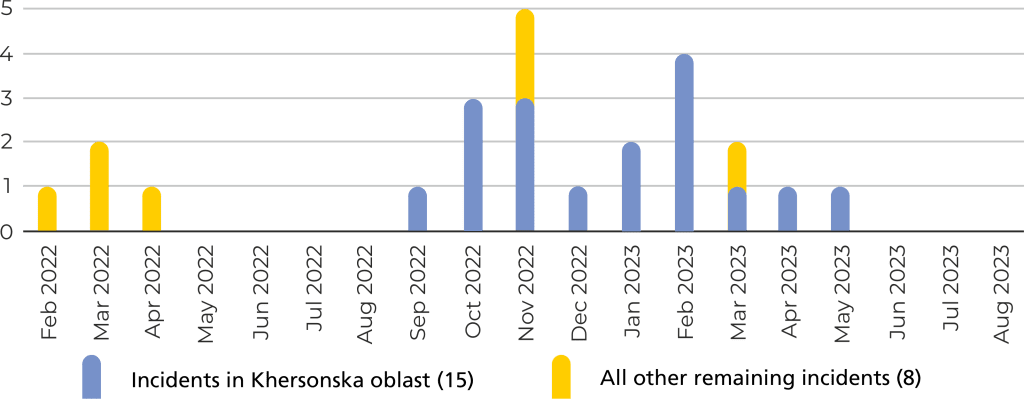

Such incidents were more frequently reported between October 2022 and March 2023, with three incidents reported as taking place during the first two months of the full-scale invasion.

- Nearly two-thirds of the incidents were reported in Khersonska oblast, where 15 cases were recorded. In June 2023, one women’s hospital in Luhansk oblast had reportedly all its furniture placed into military trucks and taken away after Russian forces converted it into a field hospital for wounded Russian soldiers (incident 39856).[83]

- In eight incidents, medical supplies were specifically reported to have been requisitioned and removed by Russian military vehicles. For example:

- In October 2022, medical equipment was taken from a hospital in Bilozerka, Khersonska oblast, and transferred to Skadovsk and Henichesk (incident 35337).[84]

- In March 2023, blood supplies were taken by Russian forces from transfusion centers in Sevastopol city, Crimea, to a military hospital, which caused a shortage in civilian institutions (incident 37907).[85] While there are few details available, it appears they were taken without proper procedures.

- In the remaining 15 incidents, medical supplies were removed from a health facility. However, it is unclear if they were removed to supply health care facilities they had repurposed to treat wounded soldiers or for other unspecified purposes.

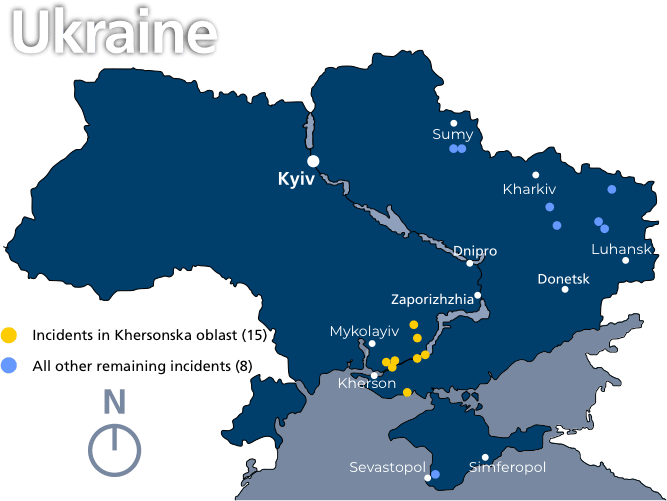

Reported locations of medical supplies requisitioned from health facilities by Russian forces, February 2022 – August 2023

On at least 23 occasions, medical supplies and equipment needed for the operation of the health system were taken by Russian forces. A large number of incidents were reported in Khersonska oblast between October 2022 and February 2023.

In Kharkivska oblast, Dr. Maryna Rudenko, director of the Balakliia Clinical Multiprofile Intensive Care Hospital, recounted living inside the facility until April 4, 2022, when Russian forces seized the hospital (incident 36559).[86] Upon her return five months later, Dr. Rudenko described the situation in this way:

“Almost everything was stolen. They took away everything that could be taken away. They couldn’t move the CT scanner, so they looted the electronics from it. … We had two surgical stands … We hid them in the basement, but they found them and stole them. All the tools were stolen. The diagnostic department: there is nothing at all, everything was stolen; they lived there. That is, all ultrasound machines, cardiographs, encephalographs; nothing. They took it out … We also had a generator for 100 kilowatts: disappeared. Out of 15 [ambulance] cars, 14 disappeared with them. Telephones, 37 washing machines, microwave ovens [were also removed].”[87]

Another doctor spoke to the MIHR researchers about the seizure of property in then-occupied Kherson before they left the city in July 2022 (incident 42145):[88]

“At the beginning of the spring of 2022, the occupation authorities banned the import of medicines into Kherson; this spurred an ‘underground’ trade in medicines throughout the city. From the start of the occupation, Russian ‘entrepreneurs’ appropriated Ukrainian pharmacies and started selling Russian medicines. They were of much lower quality than Ukrainian and European ones.”[89]

In addition to diminished access to medical services, property seizure and willful destruction have led to greater scarcity of medications and limited equipment to perform necessary tests or surgeries. Ukraine’s Ministry of Health has described the current supply levels of medicines to health care facilities and pharmacies in the areas currently occupied by Russian forces as “catastrophic,” as there are no deliveries to the occupied areas of Khersonska and Zaporizka oblasts, and the information from Donetska and Luhanska oblasts is scarce.[90]

Credible reports of medical supplies and equipment stolen by retreating Russian forces, such as the ones highlighted in Balakliia Clinical Multiprofile Intensive Care Hospital and in Kherson, require further investigation. They may amount to IHL violations and, possibly, war crimes of pillage and/or seizure of property.[91]

Forced Change of Nationality and its Consequences

Forced change of nationality – or as it is referred to in Ukraine, “passportization” – involves mandating the acquisition of Russian passports in the areas currently occupied by Russian forces, including by making access to health care conditional on one’s nationality. In this context, “passportization” refers to the coerced adoption of Russian nationality through control of access to several areas of civilian life, including access to health care.[92]

| Applicable Law Coercion of inhabitants in areas currently under Russian occupation to change nationality. One of the basic principles of occupation law states that “[i]t is forbidden to compel the inhabitants of occupied territory to swear allegiance to the hostile Power.”[93] It follows that no form of pressure can be exercised on the population to assume Russian nationality.[94] Right to a nationality.[95] According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, “[e]veryone has the right to a nationality. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.”[96] The right to a nationality, also enshrined in other human rights treaties such as the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,[97] includes both the ability to freely change one’s nationality, without coercion,[98] and the prohibition against arbitrary deprivation of one’s nationality. This includes situations where people who were recognized as citizens of a state are subsequently stripped of that nationality.[99] With specific regard to protected persons in occupied territories, IHL provides that they “shall not be deprived, in any case or in any manner whatsoever, of the benefits of the present Convention by any change introduced, as the result of the occupation of a territory, […] nor by any annexation by the latter [the Occupying Power] of the whole or part of the occupied territory.”[100] Russian policies, witnessed first in Crimea and more recently in Donetska, Khersonska, Luhanska, and Zaporizka oblasts, instituting a procedure to forcibly issue Russian passports for residents that – if rejected – will ultimately render them stateless or “foreign” citizens, would likely violate these protections. Adverse distinctions based on nationality. “Passportization” may likewise violate a range of IHL protections. The provision of medical supplies should be made “without any adverse distinction”[101] that is not based on medical or humanitarian criteria.[102] “Similarly, Article 75 of AP I would require humane treatment and fundamental guarantees to be accorded to all persons irrespective of ‘national […] origin,’ and would prohibit as discrimination all unfavorable treatment – including collective punishment –of persons compared to the treatment of persons of a different nationality (including own, enemy or third-country nationals) that has no reasonable and objective justification.”[103] The prohibition of adverse distinction is the IHL counterpart to the concept of discrimination in human rights law,[104] defined by the UN Human Rights Committee as “any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference which is based on any ground such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status, and which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by all persons, on an equal footing, of all rights and freedoms.”[105] Distinctions based on nationality in the provision of medical supplies essential to the survival of the civilian population, resulting in nationals of the occupied state being subjected to less favorable treatment compared to nationals of the Occupying Power, would seem to openly violate the IHL provision referenced above. Other violations. Using discriminatory methods to impose a change of nationality to the population of temporarily occupied areas may also result in other violations, such as the rules prohibiting forcible transfers or deportations of the population of the occupied territories,[106] and those forbidding the Occupying Power to pressure or force protected persons to serve in its armed or auxiliary forces,[107] as well as more generally depriving them of their fundamental rights. |

Coerced adoption of Russian nationality began prior to the February 2022 invasion, when Russian citizenship was automatically granted to residents of occupied Crimea and simplified procedures for Russian passport applications were introduced for Ukrainian citizens of the occupied territories of Donetska and Luhanska oblasts.[108] On April 27, 2023, President Vladimir Putin of Russia signed a decree establishing a procedure to issue Russian passports to residents of the Russian-occupied territories of Donetska, Khersonska, Luhanska, and Zaporizka oblasts of Ukraine.[109] According to the decree, residents have until July 1, 2024 to accept Russian citizenship; otherwise, they will be considered foreigners or stateless and can be detained or deported.[110] As was the case in Crimea after Russia’s occupation in 2014, they may face threats and discrimination, including in accessing medical care and social services.[111]

Concurrently, on June 20, 2023, Decree No. 186 was issued in the occupied territories of the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic,” establishing a working group vested with executive authority to expel, deport, and detain all Ukrainians who did not obtain Russian citizenship in designated camps.[112]

Conditioning Access to Care on Change in Nationality

The research team documented 15 incidents of “passportization” through medical services between February 2023 and August 2023. Most incidents took place from March 2023 onwards, with one recorded incident in September 2022 in Donetska oblast. Cases were documented in four of Ukraine’s oblasts and were most frequent in Zaporizka oblast, where eight cases were recorded. Of note:

- Five incidents involved health care workers being affected by “passportization.” During these incidents, health care workers were reportedly ordered to deny medical services to people who did not hold a Russian passport or a receipt of application.

- In some hospitals, administration points were set up for civilians to then apply for a Russian passport.

- In other cases, health care workers were reportedly forced to hand over their Ukrainian passports and obtain a Russian passport within a strict time frame or face being dismissed from their positions if they refused and their positions filled by Russian staff.

- In one case in June 2023, Russian authorities reportedly closed a health facility in Zaporizka oblast after most of the employees refused to obtain Russian passports (incident 39417).[113]

In ten incidents, civilians carrying Ukrainian passports were reportedly unable to access medical services. Five of these incidents were reported in Zaporizka oblast.

Reported locations of “Passportization” of Population Through Medical Services by Russian forces, February 2022 – August 2023

Incidents became more frequent from March 2023 onward, with most taking place in Zaporizka oblast

“Passportization”: Before and After February 2022

Before the 2022 invasion, human rights organizations in Ukraine had reported on limited access to medical services for civilians without Russian passports who were living in previously occupied territories.[114] In Crimea, for instance, medical services should have been provided free of charge, but after 2014, according to local practices these services were only available to holders of a compulsory health insurance policy for Russian citizens. Those who did not have such documentation could not obtain an appointment at a public hospital.[115]

In the words of a patient from Crimea who spoke with the human rights organization ZMINA in 2017, “I was sick, I had a fever, a cough, I went to the receptionist at the seventh polyclinic. They did not give me a referral to a doctor because I did not have their insurance, and I did not have insurance because I did not have a passport. I had to go to a doctor I knew. As a result, it turned out that I had pneumonia, and I was treated at home, with the advice of a doctor I knew.”[116]

Elsewhere, “passportization coercion is gaining momentum,” according to the advisor to the mayor of Mariupol Petro Andriushchenko.[117] In Mariupol, the advisor reports that people are now “being denied treatment and/or examination […] without state health insurance. To get insurance, you need to have a Russian passport.”

Khersonska oblast is another area that has suffered devastating destruction –from the bombing of the Kakhovka dam in June 2023[118] to incessant shelling of civilian infrastructure, including health care.[119] According to a report by the Center for Investigative Journalism, a local resident in Hornostaiyivka reportedly died because doctors refused to provide him with medical care without a Russian passport (incident 42057).[120]

In May 2023, the Russian government announced that all residents of areas occupied by Russian forces, including children, would need to obtain compulsory health care insurance available only for Russian citizens by the end of 2023.[121] According to Yuriy Sobolevsky, first deputy chairman of the Khersonska Oblast Council, doctors have already refused to provide services to those who do not have a Russian compulsory insurance policy: “Fortunately, most of the doctors are our [Ukrainian] Kherson doctors, they are sabotaging this and quietly continue to provide medical services, but some health facilities already have managers and medical staff, partly people who came from Russia to Khersonska oblast, and they are putting the most pressure on our people.”[122]

A similar situation obtains in Donetska and Luhanska oblasts. The Ukrainian government’s National Resistance Center reports that, to specifically control the process of “passportization” – and the provision of medical services based on one’s passport – the Russian “administration” is increasing the number of doctors brought in from Russia.[123]

Russian officials and their appointees confirmed the existence of these policies. In Lazurne (Khersonska oblast), for instance, the Russian-appointed head of the town, Oleksandr Dudka, stated that Russian authorities would not provide medicines and humanitarian aid to Ukrainian citizens who rejected Russian passports. In his words, “Medicines purchased from the budget of the Russian Federation will not be distributed to Ukrainian citizens. This applies to insulin users who have already experienced what it is like to be a citizen of another country.” (incident 42060)[124] Similar accounts of deprivation of access to insulin have also been reported from areas near Genichesk of Khersonska oblast.[125] The Russian-appointed head of the occupation administration of Zaporizka oblast, Yevhen Balitskyy, said that residents of the Russian-controlled part of the oblast who do not have Russian passports will not be able to use medical services from 2024.[126]

Such barriers to access to lifesaving medicines are erected throughout many areas currently under Russian occupation, in addition to the unavailability of medical services. In Enerhodar of Zaporizka oblast, which hosts the threatened Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, the largest nuclear power plant in Europe,[127] the Russian administration prohibited the distribution of vital medicines to residents without a Russian passport. According to the mayor, Dmytro Orlov, all the pharmacies were seized and now refuse to provide vital medicines, including insulin and thyroid medicines, to citizens without Russian passports (incident 42062).[128] A resident of Enerhodar said that the occupation “administration” announced that an ambulance would not come “if you did not have a Russian passport. Then they warned us that they would not sign us up for scheduled surgeries, and before the urgent ones, they force [us] to sign a commitment to get this passport or at least to sign up for it.”[129]

Amid occupation, health care workers at public health facilities are often compelled to be the initial subjects for testing the newly implemented “passportization” policies. In Mariupol, for instance, health care workers were reportedly ordered to obtain Russian passports (incident 34715).[130] Meanwhile, they were also obliged to unconditionally hand over their Ukrainian passports, making it virtually impossible for them to leave the occupied city.

Impact of “passportization” on Children and Vulnerable Groups

These restrictions are particularly harmful to vulnerable groups, including people with disabilities, chronic diseases, critical conditions, the elderly, and low-income people. Women and girls may often struggle to access essential gynecological and reproductive health care in situations where health decisions are primarily shaped by scarcity, safety concerns, and ongoing conflict.[131] Patients may not seek necessary care, subjecting themselves to greater risk of health complications.

This is especially concerning for children, given reports of denial of access to insulin or hospitalization for children whose parents do not have Russian passports or who have resisted “passportization” (incident 42120).[132] These practices are also occurring against the backdrop of mass deportations of Ukrainian children to Russia, with 150,000 to 300,000 children subjected to forcible transfer and/or deportation.[133]

Russia’s “passportization” policy seeks to forcibly change the nationality of deported and forcibly displaced citizens of Ukraine, including orphans and children left without parental care. The latter are particularly vulnerable to the policy: as per the “passportization” laws, representatives from health care facilities,[134] as well as schools and social institutions in whose care these children are kept, can request to Russian authorities on their behalf that they no longer want Ukrainian citizenship. Human rights organizations have documented deportations of entire orphanages, with more than 2,000 orphans, children without status, and children deprived of parental care taken to Russia from boarding schools and orphanages in the occupied parts of Luhanska and Donetska oblasts alone since the beginning of May 2022.[135]

Ukrainian people are being forced to choose between their well-being, even their lives, and their citizenship in exchange for basic services, including health care; indeed, Russia appears to be aiming to expedite its “passportization” of the population in Ukraine’s occupied territories. Such violations urgently require further investigation.

Health Care Workers: At Risk and Under Duress

| Applicable Law Under IHL, health care workers assigned to carry out medical duties or purposes must always be respected and protected, unless they commit, outside of their humanitarian function, acts that are harmful to the enemy.[136] They shall also be allowed to carry out their duties,[137] and must be exempted from any measures that may interfere with the performance of their professional ethical obligations including restrictions on their movements, and the requisition of their supplies, equipment, or vehicles.[138] Cooperation between the Occupying Power and national/local authorities. The Occupying Power must ensure that hospital and medical services can work properly and continue to do so, with the cooperation of national and local authorities.[139] This means that the “burden of organizing hospitals and health services […] is above all one for the competent services of the occupied country itself.”[140] The level of involvement of the Occupying Power will vary based on the extent to which national authorities are able to look after the health of the population themselves.[141] As long as they are able to meet the needs of the population, staffing decisions would thus fall on national and local authorities. Deportations and Transfers. IHL provides that the protecting party shall not transfer part of its civilian population into the territory it occupies.[142] Similarly, there is also an absolute prohibition against the forcible transfer or deportation of one or multiple protected persons from the occupied territories to the territory of the Occupying Power or to that of any other country, regardless of the motive.[143] Both of these actions may also amount to war crimes.[144] Provisional evacuations for the security of the population or dictated by imperative military reasons are the only exceptions that can justify forcing the population of the occupied territory to move elsewhere.[145] To distinguish between unlawful forcible displacement and lawful evacuations, one must consider “[w]hether (a) the purpose is to protect civilians from the effects of military attacks, or (b) it is for an illicit purpose such as to change the demographic makeup of an area or indefinitely remove inhabitants as a security buffer;”[146] indeed, political motives cannot qualify as imperative military reasons to move a population in order to exercise more effective control over dissident groups or an area.[147] Health care workers also fall under this protection regime aimed at ensuring that the makeup of the population of an occupied territory is not reshaped. Prohibition of arbitrary deprivation of liberty. Arbitrary detention is prohibited both under IHL and human rights law.[148] IHL lists lawful grounds for detention in all four Geneva Conventions. Regarding health care personnel, IHL distinguishes the treatment of civilian personnel from the ones of personnel who are part of the armed forces or work under their auspices. Civilian health care personnel may only be interned or placed in assigned residence if “the security of the Detaining Power makes it absolutely necessary”[149] or, in occupied territories, for imperative security reasons.[150] Military health care personnel, if exclusively engaged in medical activities, can be retained by the adverse Party “only in so far as the state of health […] and the number of prisoners of war require” and relieved where possible.[151] Auxiliary military health care personnel will instead be considered prisoners of war should they fall into the enemy’s hands, “but shall be employed on their medical duties in so far as the need arises.”[152] Detention that is not in conformity with IHL rules is defined as unlawful confinement and – when concerning civilians, including civilian health care personnel – amounts to a grave breach of the Fourth Geneva Convention.[153] Prohibition of torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment. There are multiple definitions of torture under public international law. According to the Rome Statute, torture is the intentional infliction of severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, upon a protected person for the purpose of, among others, obtaining information, punishment, intimidation, or coercion.[154] Inhuman treatment does not require such purpose.[155] These acts are forbidden at all times, by all parties to a conflict.[156] |

Doctors and other health care workers in conflict find themselves working in incredibly challenging conditions, often amid constant shelling. Many health care workers have become displaced, increasing the burden on the existing staff. The total health care workforce within Ukraine’s national health care system experienced a 13.7 percent reduction in 2022 compared to the previous year.[157]

Since the onset of the full-scale invasion, 160 health workers have been killed and 119 have been injured in 185 incidents.

Doctors are often sources of support; in conflict and occupation, it is common for them to assume leadership roles in their communities. Dr. Yuzvak, who was the only active doctor in Hostomel during the occupation, described her role as follows: “People, civilians, kept coming to me for medical help. We were already running out of medicines, basic medicines, for hypertension, diabetes, and it was clear that there was nowhere to buy them, people were getting contusions from explosions, they were dying, and there was nowhere to bury them. They started turning to me because they knew I was a doctor. I had to take on some kind of a leadership role.”[158]

Precisely for these reasons, however, health care workers are often singled out and targeted during conflict, particularly in situations of occupation.[159] In relation to the Russian occupation of Balakliia, Dr. Rudenko stated that: “[t]he FSB [Russia’s Federal Security Services] came to us on April 3 in the evening. They gathered all the medical staff … and said, ‘Don’t even think about going anywhere, you have to live here, you have to work here. We need to establish communication with the local population, so we will not let the doctors leave the city.’”[160]

| A doctor from the Kherson Regional Clinical Hospital spoke to MIHR about providing health care under occupation on the condition of anonymity:[161] “On July 1, 2022, representatives of the Federal Security Service of Russia came to the Regional Clinical Hospital; they detained the director of medical affairs and the head of the hospital’s personnel department. In order to contain the doctors’ discontent, the Federal Security Service took some of the Ukrainian doctors away for “a conversation” or summoned them to the occupied Department of Health [to limit the spread of rebellion].” |

Detention of Health Care Workers

During Russia’s invasion, hundreds of health care workers have been detained, arrested, or otherwise persecuted by Russian forces. Although the Russian Federation refuses to provide access to detention centers and confirm the exact numbers of civilians in captivity as well as prisoners of war, “Military Medics of Ukraine,” a nongovernmental organization that works to help free Ukrainian medics who are being held captive, indicates that, based on information from Ukrainian state bodies, approximately 500 medics, both military and civilian, are currently thought to be held captive by Russian forces.[162] MIHR researchers identified 42 places of detention in the Russian Federation – pretrial detention centers and penal colonies, located both in the regions bordering Ukraine and farther in the country. Some prisoners are also held in the occupied territories of Donetska and Luhanska oblasts.[163]

According to the research team’s database, at least 68 health care workers were detained by Russian forces or supporting forces in 17 incidents between February 2022 and August 2023. These arrests occurred in four of Ukraine’s 24 oblasts and were most frequent in Khersonska oblast, which documented eight incidents and Donetska which documented six incidents. Kharkivska, Kyivska, and Zaporizka oblasts each recorded one incident respectively. Of note:

- Health worker detentions were most common in 2022, with one incident reported in 2023 involving a female paramedic being taken from her home in Tarasivka village, Zaporizka oblast, in January by Chechen forces who threatened to deport her for refusing to cooperate (incident 36880).[164]

- Health workers were mostly detained in small groups (numbering between one and three) with one incident where 42 medics were arrested in April and May 2022 (incident 34716).[165] During that incident, and notwithstanding the special status afforded medics under IHL, Russia held an unspecified number of doctors of Hospital No. 555 as “prisoners of war” who were sheltering at the Ilyich metallurgical plant.[166]

Reported locations where health workers were arrested by Russian forces, February 2022 – August 2023

At least 68 health care workers were detained in 17 incidents by Russian or supporting forces. All but one arrest occurred in 2022, with incidents frequent in Donetska and Khersonska oblast and one each in Kharkivska, Kyivska, and Zaporizka oblasts.

A doctor from the Kherson Regional Clinical Hospital in then-occupied Kherson, who was interviewed by MIHR researchers on the condition of anonymity, stated that, “It was dangerous for Ukrainian doctors to work under occupation, especially in small villages, as they could become victims of abductions. First, there are fewer witnesses to abductions in towns and villages; second, it is easier to pressure and force cooperation. The reason for the abduction could be the refusal to take Russian salaries or social assistance, or the compulsion to travel for retraining, which had been announced in June 2022.”[167]

| During the occupation of Hostomel in Kyivska oblast in March 2022, Olena Yuzvak, head of the Hostomel Primary Care Center, was taken for interrogation by Russian soldiers where she had a plastic bag put over her head and was suffocated for up to 30 seconds (incident 42071): [168] “On March 20, Russian soldiers came to our home in a private house. The Russian soldiers shot my husband in the knee and thigh with a gun, put him on the ground, and put the gun to his head. My son came out of the house [….] They put the three of us in an armored personnel carrier, blindfolded us and took us to their headquarters in Hostomel in the Yagoda residential complex. The interrogation was tough [….] Moreover, my husband was not provided with medical care, he was bleeding from the leg, he had two bullet wounds. During the interrogation, they asked me what I do, and I said that I am a doctor and that I have been working only in health care for more than 20 years. And after the interrogation, they put us in the corridor, put bags on our heads, tied our hands with tape, and started twisting and strangling us with tape around our necks. [….] As a doctor, I understand that asphyxiation is an easy death [….] I accepted it, that that’s the way it should be. Then, when they saw that we started to suffocate, they cut holes in our bags and took us all to Antonov airport for further interrogation. They left my husband and son there. And I was brought back to this Yagoda residential complex, where I was held captive for a day.” |

Health care workers, among many other prisoners held by Russia that return from captivity, report poor living conditions, torture, and ill-treatment.[169] A military medic, who was captured in Mariupol and later released as part of an exchange of prisoners, recounted:

“Upon arriving at the colony, we underwent an ‘admission’ procedure. As soon as we got off the bus, the jailers identified and continued to beat us: while we were saying our names, then again along a corridor they formed, and finally after they forced us to squat down. There was constant physical violence. They could have let this bus in without this ‘ritual,’ everyone knew the bus was carrying wounded people and doctors. But the wounded were not spared. There was a guy with a crutch; they took the crutch from him and beat him with it, even as he fell to the ground. A wounded prisoner of war, who survived two airstrikes and had facial burns, was beaten to death.” [170]

These reports, including that of Dr. Yuzvak, demand investigation, together with other allegations of torture and ill-treatment of doctors emerging from places of internment.[171]

Coercion of Doctors: Violations of Medical Ethics

Applicable Law

Medical personnel and other health care professionals may not be punished for acting in conformity with medical ethics.[172] These include the ethical obligations to provide impartial care, to center the health and wellbeing of patients in medical decision making, and to protect the confidentiality of information obtained while treating patients.[173] The reported examples from the areas currently under Russian occupation discussed in this report – such as being compelled to deny care to people on the basis of their nationality and to transfer confidential patient data to government authorities – constitute clear violations of medical ethics.

Russian authorities have often forced health care workers to violate their professional and ethical obligations to their patients. As PHR has documented in other contexts, such circumstances could be characterized as “dual loyalty” situations, in which compliance with Russian demands conflicts with their professional and ethical obligations to their patients.[174]

Being coerced to deny medical care to persons who refuse to secure a Russian passport is one such example of direct interference with medical ethics. Furthermore, clinicians who refuse to obtain a Russian passport may also face sanctions or reprisals. In September 2023, Russian military reportedly abducted and killed 26-year-old Anastasia Saksaganska, a doctor from the village of Mali Kopani, Khersonska oblast, as well as her husband.[175] Their relatives stated that the reason for their death was their refusal to obtain Russian passports and submit to Russian demands. Another example was provided by a doctor from the Kherson Regional Clinical Hospital in then-occupied Kherson, who was interviewed on the condition of anonymity. They described medical personnel being commanded to transfer confidential patient data to Russian government authorities:

“The new occupation authorities demanded access to the electronic database of patients, ‘e-Health,’ from Ukrainian doctors; they asked which of my patients receive insulin and how much it costs. The database stores confidential information, accessible only to medical personnel. In addition to home addresses and phone numbers, it stores passport data and contact information. Special population groups are also indicated, including veterans of [Ukraine’s] Anti-Terrorist Operation. I was worried, because the week before, I had received a patient from the occupied city of Mykolaiv oblast; he was a former member of the Anti-Terrorist Operation suffering from diabetes. The Russians found out about his illness, arrested him, and waited for him to die slowly without insulin. The man somehow managed to escape. I gave him the contacts of acquaintances who [later] sheltered him.” [176]

Russian-controlled Health Service Delivery

The full-scale invasion has paralyzed the health care system in areas currently under Russian occupation. While exact numbers are unknown, in Mariupol alone, over 30 doctors were confirmed to have been killed during the first months of the invasion.[177] Increasingly, because of the shortage of medical personnel, Russian doctors are being brought into the occupied regions to replace Ukrainian doctors, work alongside them, and often lead health care facilities or departments. Working alongside doctors from an aggressor country is not only difficult on a personal level for many Ukrainian health care workers, but also poses logistical and administrative challenges: the health care systems of Ukraine and Russia are organized very differently. In addition, this often causes conflicts among medical personnel. As the doctor from the Kherson Regional Clinical Hospital explained:

“They [Russian doctors] said that we had destroyed the health care system, that we had few hospitals, few departments. They did not understand what electronic databases were, what confidentiality meant, that not everyone should see the data. [….] They did not communicate with our staff. Our staff were used only as servants. They cleaned up after the Russians, did laundry, and organized their everyday life. The Russians treated the Ukrainian workers with disdain.”[178]

In Mariupol, for example, Russian doctors reportedly came to work at the city emergency hospital led by the chairman of the State Duma Committee on Health, who publicly cheered Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and was later sanctioned by a number of states.[179] Russian doctors were also reportedly brought to Zaporizka oblast,[180] where, according to other reports, hospitals barely had a hundred employees instead of the required 500.[181]

| A Ukrainian doctor from the Kherson Regional Clinical Hospital spoke to MIHR about providing health care under occupation. In their words:[182] “Some of them [Russian doctors] came under duress, but there were also those who openly said that they came here to earn money. They were paid 200–300 thousand rubles, like the military. But there were also the ideologically driven who came to ‘help.’ The Russians forcibly gathered all the doctors [at the occupation administration]. The illegal director of the Skadovsk hospital was there, and someone else came from the medical directors of the left bank [of the river]. They were gathering us there to ask us to cooperate on documents. They wanted to appoint us to positions in the Russian occupation administration in the ‘Ministry of Health’ so that we could re-register as Russian doctors and undergo retraining. The meeting was chaired by the former Minister of Health of the [Russian] Republic of Tyva. He was appointed as a curator from Moscow.” |

It is currently unclear what protocols are being followed, if any, in the health facilities of Ukraine’s occupied territories. A new Russian federal law regulating the health care system on the occupied territories mandates Ukrainian doctors and pharmacists to obtain accreditation in accordance with Russian health care laws by the end of 2025.[183] Particularly concerning is a provision of the law that allows medical care to be provided without taking into account clinical practice guidelines for the duration of the transition period until 2025, likely eroding the standards of an already weakened health care system in these areas. Such immediate rescission of administrative regulations would also appear to run afoul of IHL’s requirement that the status quo ante in Ukraine’s occupied territories be preserved to the extent possible. Moreover, the negative impact such Russian-imposed changes are likely to have on the broader civilian population’s access to health service delivery further underscores the coercive aspect of these regulations.

Accountability for Attacks on Health Care: An Urgent Priority

The destructive impact of a compromised health care system threatens to impose long-lasting and severe hardship on Ukraine’s people. The Russian Federation must end its aggression, cease its violations, and return the administration of Ukraine’s health care system back to the Ukrainian government.

Pending such a return, protecting health care remains an obligation under international humanitarian law. This includes the protection of health care personnel, patients, and facilities from attack and ensuring the access of all populations in need of health care to adequate and timely care, with no adverse discrimination. Detained medics must also be released.

There remains a pressing need to ensure accountability for violations of IHL with respect to health care, for which there has been almost complete impunity in both Ukraine and globally. To that end, this study urges all investigative and prosecutorial bodies with relevant jurisdiction – including the International Criminal Court’s Office of the Prosecutor, the Prosecutor General of Ukraine, the UN’s Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine, and other national prosecutors – to prioritize the investigation of attacks on health care. This includes the unlawful repurposing of civilian hospitals and the ill-treatment of health care workers in Ukraine’s occupied territory, which may constitute war crimes, and the policy and practice of conditioning access to health care and other services on the forced change of nationality.

Acknowledgments

This case study is a joint product of eyeWitness to Atrocities (eyeWitness), Insecurity Insight, the Media Initiative for Human Rights (MIHR), and Physicians for Human Rights (PHR).

It was researched and written by Christian De Vos, MSc, JD, PhD, PHR director of research and investigations; Anna Gallina, LLM, advanced LLM, eyeWitness associate legal advisor; the MIHR team; Uliana Poltavets, MSc, PHR Ukraine emergency response coordinator; and Christina Wille, MPhil, Insecurity Insight director. Will Jaffe, PHR advocacy coordinator, also contributed to the drafting and preparation of the study.

The case study was reviewed by the eyeWitness team; the MIHR team; and PHR staff members Erika Dailey, MPhil, director of advocacy and policy; Michele Heisler, MD, MPA, medical director; Karen Naimer, MA, JD, LLM, director of programs; Kevin Short, deputy director, media and communications; and Sam Zarifi, JD, executive director.

Interviews were carried out by staff members of the Ukrainian Healthcare Center (UHC) and published here with UHC’s permission; Uliana Poltavets, PHR; and by the MIHR research team.

The report received external review from Leonard S. Rubenstein, JD, LLM, distinguished professor of the practice at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and chair of the Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition, as well as Ana Elisa Barbar, formerly of the International Committee of the Red Cross, and Rudi Coninx, MD, MPH, formerly of the World Health Organization.

The study was reviewed, edited, and prepared for publication by PHR’s senior publications consultant, Rhoda Feng.

Endnotes

[1] The World Health Organization defines an attack on health as “any act of verbal or physical violence, obstruction, or threat of violence that interferes with the availability of, access to, and delivery of curative and/or preventive health services during emergencies.” In this sense, attacks on health happen not only when hospitals and clinics are damaged and destroyed but also when access to health services is impeded or denied through an array of other methods, such as described below. “Attacks on Health Care Initiative,” World Health Organization, July 22, 2020, https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/attacks-on-health-care-initiative.

[2] “Attacks on Health Care in Ukraine,” eyeWitness to Atrocities, Insecurity Insight, Media Initiative for Human Rights, Physicians for Human Rights, and Ukrainian Healthcare Center, last modified September 11, 2023, https://www.attacksonhealthukraine.org/.

[3] “Attacked and Threatened: Health Care at Risk,” Insecurity Insight, accessed September 4, 2023, https://mapaction-maps.herokuapp.com/health.

[4] “Attacks on Health Care in Ukraine,” eyeWitness to Atrocities, Insecurity Insight, Media Initiative for Human Rights, Physicians for Human Rights, and the Ukrainian Healthcare Center.

[5] The Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine deplored “that attacks continue to take place harming civilians and medical institutions which have protected status.” “Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine,” United Nations Human Rights Council, September 25, 2023, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/hrbodies/hrcouncil/coiukraine/20230923-Oral-Update-IICIU-EN.pdf; The UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment also noted that the “volume of credible allegations of torture and other inhumane acts […] appear neither random nor incidental, but rather orchestrated as part of a State policy to intimidate, instill fear, punish, or extract information and confessions.” “Russia’s war in Ukraine synonymous with torture: UN expert,” United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, September 10, 2023, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/09/russias-war-ukraine-synonymous-torture-un-expert#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThese%20grievous%20acts%20appear%20neither,an%20official%20visit%20to%20Ukraine.

[6] “Destruction and Devastation: One Year of Russia’s Assault on Ukraine’s Health Care System,” eyeWitness to Atrocities, Insecurity Insight, Media Initiative for Human Rights, Physicians for Human Rights, and Ukrainian Healthcare Center, February 2023, https://phr.org/our-work/resources/russias-assault-on-ukraines-health-care-system.

[7] “Healthcare at War: The Impact of Russia’s full-scale Invasion on the Healthcare in Ukraine,” Ukrainian Healthcare Center (UHC), April 2023, p. 3-4, https://web.archive.org/web/20230528004056/https://uhc.org.ua/en/2023/04/26/healthcare-at-war-eng/.

[8] UHC’s research indicates that the overall number of primary care encounters in Ukraine dropped by 28.8 percent since Russia’s full-scale invasion began – from 92.4 million in 2021 to 65.8 million in 2022. “Healthcare at War,” UHC, https://web.archive.org/web/20230528004056/https://uhc.org.ua/en/2023/04/26/healthcare-at-war-eng/.