Executive Summary

The United States maintains the world’s largest immigration detention system, detaining tens of thousands of people in a network of facilities, including those managed by private prison corporations, county jails, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). At the time of writing, ICE is detaining over 35,000 people, including long-term residents of the United States, people seeking asylum, and survivors of trafficking or torture. Instead of finding refuge, these people are held in ICE custody for extended periods, enduring inhuman conditions such as solitary confinement (dubbed “segregation” by ICE), where they are isolated in small cells with minimal contact with others for days, weeks, or even years. In many instances, such conditions would meet the definition of torture, or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment under international human rights law.

Solitary confinement causes a range of adverse health effects, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), self-harm, and suicide risks. Prolonged confinement can lead to lasting brain damage, hallucinations, confusion, disrupted sleep, and reduced cognitive function. These effects persist beyond the confinement period, often resulting in enduring psychological and physical disabilities, especially for people with preexisting medical and mental health conditions or other vulnerabilities.

In recognition of this well-documented harm, ICE issued a directive in 2013 to limit the use of solitary confinement in its facilities, especially for people with vulnerabilities. A 2015 memorandum further protected transgender people, emphasizing solitary confinement as a last resort. In 2022, ICE reinforced reporting requirements for people with mental health conditions in solitary confinement, highlighting the need for strict oversight. Despite these directives, however, government audits and whistleblowers alike have repeatedly revealed stark failures in oversight.

This report – a joint effort by Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), Harvard Law School’s Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program (HIRCP), and researchers at Harvard Medical School (HMS) – provides a detailed overview of how solitary confinement is being used by ICE across detention facilities in the United States, and its failure to adhere to its own policies, guidance, and directives. It is based on a comprehensive examination of data gathered from ICE and other agencies, including through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, first filed in 2017, and partly acquired after subsequent litigation. It is further enriched by interviews with 26 people who were formerly held in immigration facilities and experienced solitary confinement over the last 10 years.

The study reveals that immigration detention facilities fail to comply with ICE guidelines and directives regarding solitary confinement. Despite significant documented issues, including whistleblower alarms and supposed monitoring and oversight measures, there has been negligible progress. The report highlights a significant discrepancy between the 2020 campaign promise of U.S. President Joseph Biden to end solitary confinement and the ongoing practices observed in ICE detention. Over the last decade, the use of solitary confinement has persisted, and worse, the recent trend under the current administration reflects an increase in frequency and duration. Data from solitary confinement use in 2023 – though likely an underestimation as this report explains – demonstrates a marked increase in the instances of solitary confinement.

This report exposes a continuing trend of ICE using solitary confinement for punitive purposes rather than as a last resort – in violation of its own directives. Many of the people interviewed were placed in solitary confinement for minor disciplinary infractions or as a form of retaliation for participating in hunger strikes or for submitting complaints. Many reported inadequate access to medical care, including mental health care, during their solitary confinement, which they said led to the exacerbation of existing conditions or the development of new ones, including symptoms consistent with depression, anxiety, and PTSD. The conditions in solitary confinement were described as dehumanizing, with people experiencing harsh living conditions, limited access to communication and recreation, and verbal abuse or harassment from facility staff.

ICE oversaw more than 14,000 placements in solitary confinement between 2018 and 2023. Many people who are detained in solitary confinement have preexisting mental health conditions and other vulnerabilities. The average duration of solitary confinement is approximately one month, and some immigrants spend over two years in solitary confinement.

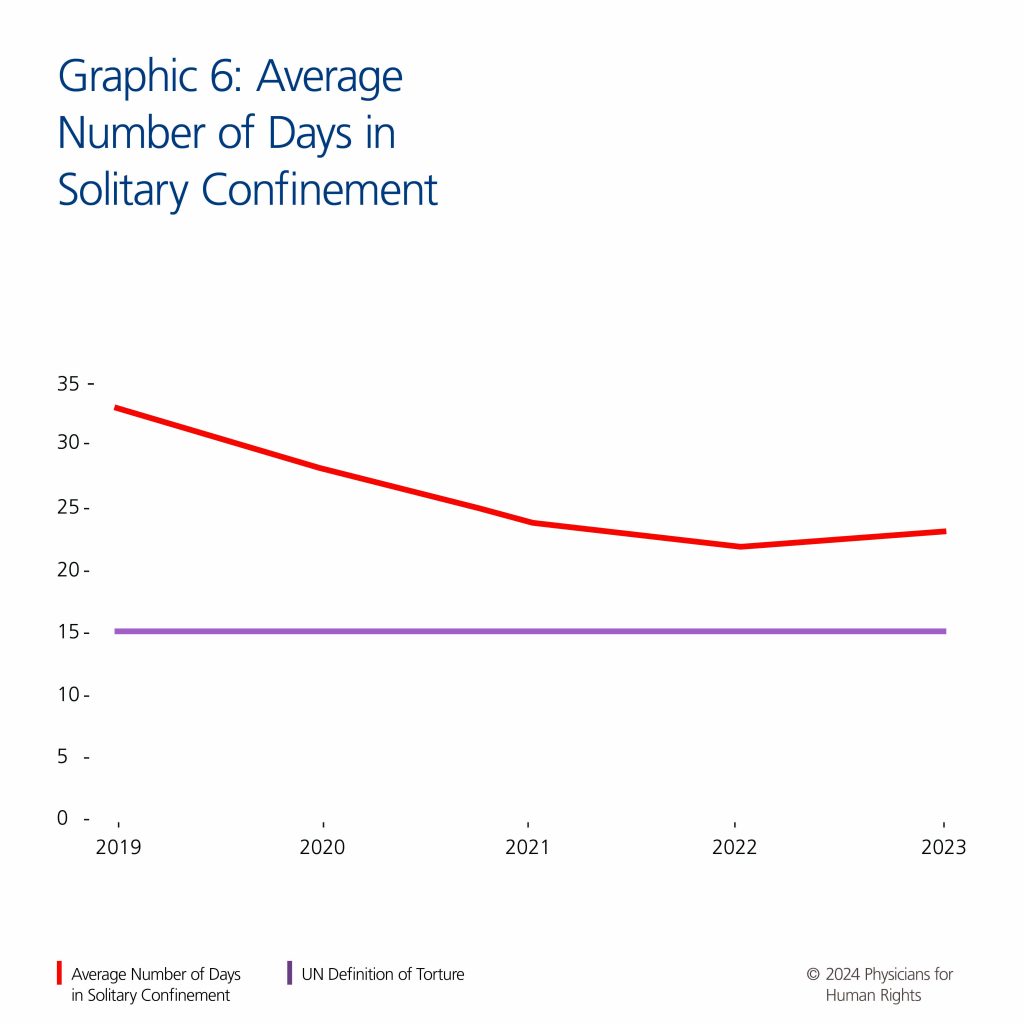

Analysis of FOIA data revealed persistent and prolonged use of solitary confinement and demonstrated significant inadequacies of current oversight and accountability mechanisms. In the last five years alone, ICE has placed people in solitary confinement over 14,000 times, with an average duration of 27 days, well exceeding the 15-day threshold that United Nations (UN) human rights experts have found constitutes torture. Many of the longest solitary confinement placements involved people with mental health conditions, indicating a failure to provide appropriate care for vulnerable populations more broadly.

Some solitary confinement placements lasted significantly longer, with 682 lasting at least 90 days and 42 lasting over one year. Many of these instances involved people with mental health conditions and other vulnerabilities, including 10 of those 42 placements lasting over a year in solitary confinement. Data provided by ICE also demonstrated a disproportionately harmful impact on people with vulnerabilities, particularly transgender people and those with mental health and medical conditions.

The treatment of people in immigration detention facilities and the excessive, punitive use of solitary confinement is not only contrary to ICE’s own policies and guidance but also violates U.S. constitutional law and international human rights law. The Fifth Amendment prohibits the deprivation of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, protection that extends to all persons within the United States, including people in immigration detention. The government has a duty to ensure the health and safety of people in immigration detention facilities, providing for their basic needs such as food and medical care. Persons in detention also have First Amendment rights, including the freedom to protest conditions or report issues without fear of retaliation.

International human rights law has also made clear that the detention of immigrants, especially in solitary confinement, should be a last resort, for the shortest time possible, and used only for limited purposes. The United States has signed and ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which prohibits arbitrary and unlawful detention. The use of prolonged solitary confinement, especially for people with mental health conditions, is prohibited under the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules). The United States has also signed and ratified the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. The UN Special Rapporteur on Torture has highlighted the severe psychological and physical harm caused by prolonged solitary confinement, especially for people with mental health conditions.

ICE’s failure to adhere to domestic and international law and its own guidelines has created dangerous conditions in detention centers, particularly for people with mental and medical health conditions or other vulnerabilities. The persistent use of solitary confinement over the last decade underscores the need for radical changes in ICE policy and practice. The evidence of profound physical and mental health deterioration caused by solitary confinement, in combination with ICE’s inability to implement policies around its use that adhere to its own guidelines as well as constitutional and international law, necessitates an immediate commitment by ICE to end the practice entirely. Prior to publication, the authors of this report had the opportunity to present the findings to key personnel in DHS and ICE.

The report makes the following recommendations to the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and to the Director of ICE, which serve as a road map to completely phase out the use of solitary confinement in immigration detention.

1. Publicly commit to ending the use of solitary confinement in all immigration detention facilities. As it abandons solitary confinement, DHS and ICE must express this commitment in the form of a binding directive. The directive should:

- Require a presumption of release from ICE detention for people who have reported existing vulnerabilities, including, but not limited to, people with serious medical conditions, mental health conditions, disabilities, LGBTQIA+ people, and survivors of torture and/or sexual violence. These people should be released into the safety of their community with post-release care plans in place, per the 2022 ICE directive, in addition to providing resources and referrals for social, legal, and/or medical services as appropriate.

- Mandate that any person in detention be afforded 24-hour access to qualified mental and medical health care professionals who respond in a timely manner and in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

- Require increased transparency from ICE’s Detention Monitoring Council by making properly redacted or deidentified reports and reviews related to solitary confinement publicly available on the agency’s website within 72 hours of the order to place someone in solitary confinement.

2. Amend the 2013 “Segregation Directive” to ensure that every immigration detention facility, public or privately contracted, is required to report concurrently to ICE Field Office Directors and ICE headquarters within 24 hours of placing someone in solitary confinement. ICE headquarters, in turn, must share this consolidated “segregation”/solitary confinement data with the DHS Office of the Secretary within 72 hours. This requirement must apply to every confined person, regardless of the duration of their confinement or whether they have a vulnerability. Additionally:

- For those who are currently in solitary confinement, require a prompt and meaningful psychosocial and medical evaluation, undertaken by qualified medical professionals, who can assess the prevalence and extent of existing vulnerabilities;

- For those scheduled for placement in solitary confinement, require a meaningful psychosocial and medical evaluation by qualified medical professionals who can assess the prevalence and extent of existing vulnerabilities prior to such a placement;

- Mandate the reporting of race and ethnicity of each person in solitary confinement;

- Mandate reporting of the justification provided for initial confinement; justification for continued confinement; duration of the confinement; any vulnerabilities identified; and a detailed description of the alternatives to solitary confinement that were considered and/or applied, as listed in 5.3.(2) of the 2013 “Segregation Directive.”

- Require daily checks and regular monitoring and documentation by qualified and licensed health care professionals against a detailed checklist created in partnership with independent medical professionals, that includes reviewing vital signs, checking for signs of self-harm, and any other indicators of deteriorating mental and physical health;

- Require the routine sharing by ICE of deidentified data acquired from the above reporting mechanisms on its website every two weeks as part of its release of Detention Statistics, until it has ended the use of solitary confinement.

3. Revise current contracts and agreements with immigration detention facility providers and contractors to include stringent performance standards and clear metrics for compliance regarding the use of solitary confinement. Compliance should be assessed through regular and comprehensive inspections by the Contracting Officer. Additionally, to increase adherence to detention standards, ICE must:

- Introduce a performance-based contracting model, where a portion of payment is contingent upon meeting certain performance and reporting indicators, including those listed in recommendations 1 and 2 herein; and

- Impose immediate financial penalties for any violation of performance and reporting indicators, and contract termination for repeated or persistent violation.

4. Establish a task force led by the Office of the Secretary of DHS to develop a comprehensive plan including specific recommendations for phasing out the use of solitary confinement. The task force must include:

- Members with knowledge of, or expertise regarding, the mental and physical health consequences of the use of solitary confinement;

- Independent medical experts;

- Independent subject matter experts from civil society (including those with expertise in the use of solitary confinement in criminal and civil custodial settings and human rights);

- Formerly detained immigrants who have experienced solitary confinement in ICE custody; and

- Employees of the following offices:

- Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL);

- ICE Health Services Corps (IHSC);

- Immigration Detention Ombudsman (OIDO);

- Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO); and

- Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR).

The plan must be presented to Congress and publicly accessible on ICE’s website upon completion, which shall be no later than one year after formation of the task force. Finally, recommendations included in the plan should ensure the end of ICE’s use of solitary confinement in immigration detention within one year of presentation of the plan to Congress and the public.

Introduction

The United States operates the world’s largest immigration detention regime. On any given day, tens of thousands of adults and children are detained in a vast network of facilities, including those operated by private prison corporations,[1] county sheriffs, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). Immigration detention is legally considered civil rather than criminal custody, but many immigrants are held in correctional facilities, which means the conditions of confinement are often the same as criminal incarceration.

As of the writing of this report, ICE is currently detaining more than 35,000 people.[2] These include people who have built a life in the United States for decades as well as people who have recently arrived seeking asylum, including trafficking or torture survivors who fled their home countries for their own safety. Those hoping to find refuge in the United States are instead imprisoned, often for months or even years while they wait for their immigration applications to be resolved or to be deported. As they wait, they are frequently subjected to inhuman conditions, including, as this report details, the danger, indignity, and harm of solitary confinement – being held in small cells with little or no contact with other people for days, weeks, or even years at a time.[3]

Given the lack of oversight and transparency regarding the use of solitary confinement in immigration detention, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), along with faculty and students at Harvard Law School (HLS) and Harvard Medical School (HMS), have sought to spotlight what is happening in the “black box” of solitary confinement in ICE detention centers. This report is the culmination of that work and reflects years of research, to uncover how many people have been held in solitary confinement, the conditions in solitary confinement, the sense of helplessness felt by those subject to solitary confinement – sometimes for months or even years – and the harmful impact of solitary confinement on people after their release from detention.

Much of the data in this report was obtained by faculty and students at HLS through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests and subsequent litigation that builds on records previously obtained by the Project on Government Oversight (POGO) and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). This report also draws on dozens of personal interviews with survivors of solitary confinement conducted by faculty and students at HMS. This report details the abusive and excessive use of solitary confinement in immigration detention. For example, ICE oversaw more than 14,000 placements in solitary confinement between 2018 and 2023. Many people who are detained in solitary confinement have preexisting mental health conditions and other vulnerabilities.[4] The average duration of solitary confinement is approximately one month, and some immigrants spend over two years in solitary confinement, [5] illustrating how concerns repeatedly raised by members of Congress and government auditors, and whistleblowers alike about the prolonged and excessive use of solitary confinement have been ignored.[6]

Background

Solitary Confinement in ICE Detention

Solitary confinement is generally defined as isolating someone in a cell for 22 hours or more per day without meaningful human contact.[7] However, ICE describes this practice euphemistically as “segregation” or “segregated housing,” using it as both punishment (termed “disciplinary segregation”) and ostensibly for safety (“administrative segregation”).[8] In this report, the term “solitary confinement” will be consistently used, unless directly quoting ICE or other official government records where the term “segregation” was applied. Notably, the need for medical isolation when no “designated medical unit exists” is one stated purpose of administrative “segregation.” However, this is in stark contrast to standard medical care of patients who need isolation for medical reasons. In the latter, isolation rooms are simply normal rooms with windows and regular furniture and bedding but the influx and egress of persons are controlled. Rooms are not locked, isolated persons do not lose most of their “privileges,” and while confined, one is made to feel like a patient, not a prisoner.

The adverse health effects of solitary confinement are well-documented and include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and increased risks of self-harm and suicide.[9] According to research, isolation can cause lasting brain damage and trigger symptoms such as hallucinations, confusion, heart palpitations, disrupted sleep, and reduced cognitive function.[10] These symptoms can extend beyond the period of solitary confinement and affect people after their release by causing enduring psychological and physical disabilities and impairments.[11] For people with preexisting medical and mental health conditions, solitary confinement can worsen existing conditions and even lead to suicide.[12] Solitary confinement thus exacerbates the well-documented high rates of suicide of immigrants in ICE detention.[13]

International law clarifies that prolonged solitary confinement “can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment when used as a punishment … for persons with mental disabilities or juveniles.”[14] As such, in 2011 the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture called for an “absolute prohibition” on solitary confinement for more than 15 days.[15] Additionally, the Rapporteur recognized that shorter periods of solitary confinement for legitimate disciplinary reasons can constitute “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment where the physical conditions of prison regime (sanitation, access to food and water) fail to respect the inherent dignity of the human person and cause severe mental and physical pain or suffering.”[16]

ICE Directives on Solitary Confinement

2013 “Segregation Directive”

After years of documentation and advocacy by civil society, ICE issued a directive in 2013 – over a decade ago – that mandates limiting and monitoring the use of solitary confinement in immigration detention. The 2013 “Segregation Directive” describes two forms of solitary confinement: administrative segregation and disciplinary segregation.[17] Before someone can be placed in disciplinary segregation, the directive states that there must be a hearing and a finding by a disciplinary panel.[18]

According to the 2013 “Segregation Directive,” administrative segregation is “a non-punitive form of separation from the general population” and is authorized “only as necessary to ensure the safety of the detainee, facility staff, the protection of property; or the security or good order of the facility.”[19] Consequently, the directive warns that placement in solitary confinement “is a serious step that requires careful consideration of alternatives” before it is used.[20] For people with special vulnerabilities, such as those with mental health conditions, serious medical conditions, disabilities, LGBTQ+ people, and torture, trafficking, and trauma survivors, the directive mandates that solitary confinement should be “only used as a last resort and when no other viable housing options exist.”[21] Facilities must notify the ICE Field Office Director (FOD) if someone has a special vulnerability as soon as possible but not more than 72 hours after placement in solitary confinement, or when anyone has been placed in solitary confinement for 14 consecutive days or 14 days in a 21-day period.[22]

Special Protections for Vulnerable Populations

2015 Memorandum: Transgender People in Detention

In 2015, ICE issued a memorandum emphasizing the need for additional protections for transgender people in detention. Like the 2013 “Segregation Directive,” the 2015 guidance emphasized that transgender people should be placed in solitary confinement only “as a last resort and when no other temporary housing option exists.”[23] Under the guidance, if a facility cannot meet this requirement or if there are concerns about the conditions of confinement, ICE is required to examine whether transferring the person to a different facility is a viable option.[24]

2022 Directive: “Individuals with Serious Mental Illness”

In 2022, ICE issued a further directive related to detained persons with serious mental health conditions that reiterated the heightened reporting requirements when placing such persons in solitary confinement.[25] The directive further echoed the 2013 “Segregation Directive” by specifically mandating that facilities notify the ICE FOD and the ICE Office of the Principal Legal Advisor within 72 hours of placing any immigrant with a serious mental health condition in solitary confinement. [26]

ICE Solitary Confinement Oversight Mechanisms

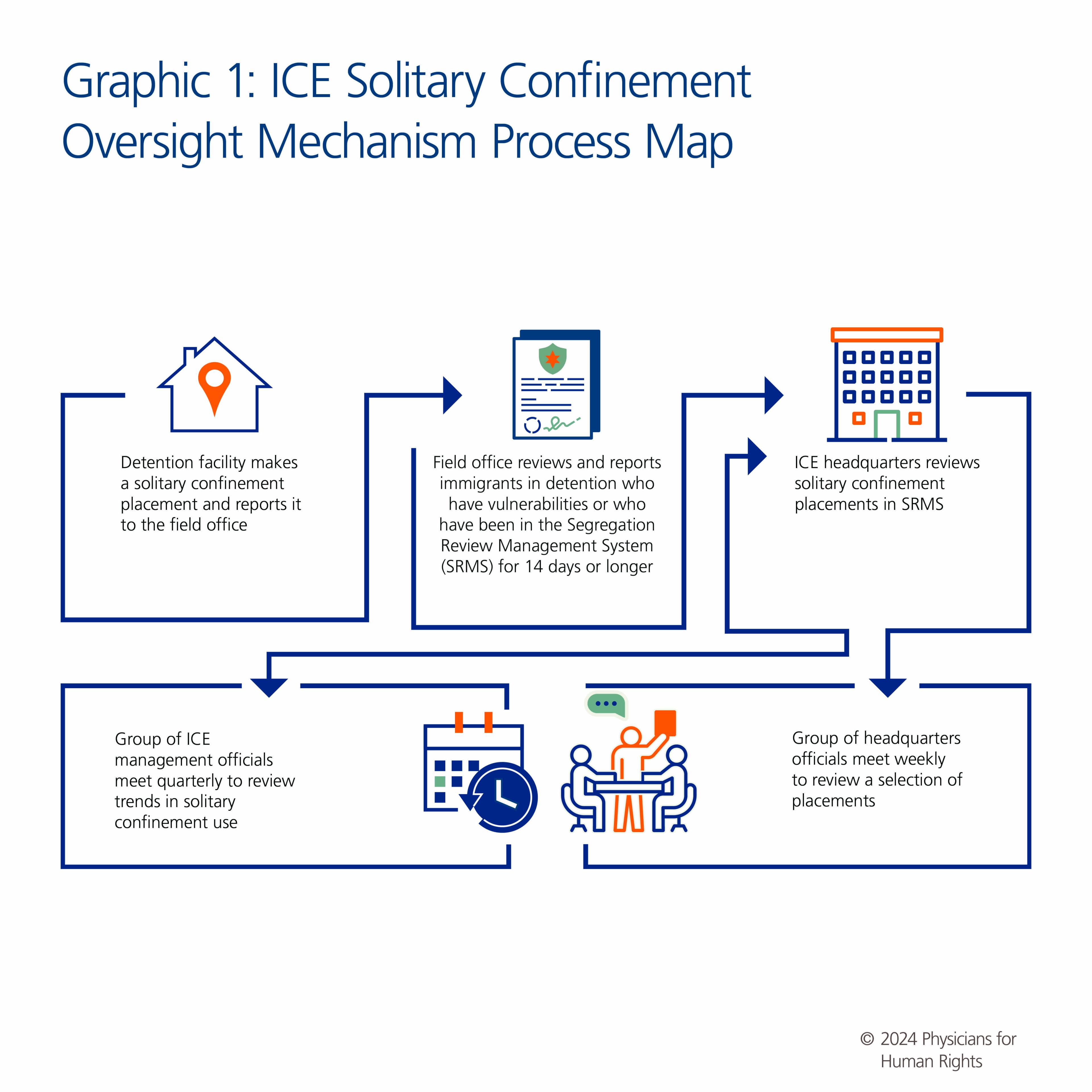

The 2013 “Segregation Directive” requires FODs to collect data from facilities on their use of solitary confinement so that ICE headquarters can provide oversight. Specifically, immigration detention facility administrators are required to notify FODs within 72 hours of the use of solitary confinement on anyone who has medical or mental illness, has a special vulnerability and/or because the detained person is an alleged victim of sexual assault, is an identified suicide risk, or is on hunger strike.[27] The 2013 “Segregation Directive” also mandates reporting on the prolonged use of solitary confinement for any person with or without these vulnerabilities when they have been held “for 14 days, 30 days, and at every 30-day interval thereafter” or “for 14 days out of any 21 day period.”[28]

ICE’s oversight mechanism for solitary confinement has been described in more detail by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) in a 2022 report.[29] Per the report, ICE headquarters staff within “Custody Management” conduct reviews of all solitary confinement placements in what is known as a “Segregation Review Management System” (SRMS).[30] The staff review compliance with ICE detention standards and directives. Representatives of a select group of ICE offices, including Custody Management, Office of the Principal Legal Advisor attorneys, and ICE Health Service Corps, also conduct weekly reviews for compliance with detention standards.[31]

ICE also maintains a “Detention Monitoring Council,” comprised of management officials who meet quarterly to discuss overall detention-related issues, including solitary confinement. Headquarter officials from Custody Management present a report on solitary confinement statistics, which includes, among other things, length of solitary confinement, reasons for confinement, and how many [individuals] were considered members of vulnerable populations.[32]

In addition to oversight through the mechanisms described above, solitary confinement practices are also monitored through facility inspections and onsite monitoring of detention standards compliance, including by independent inspectors, and by the DHS Office of Inspector General (OIG).[33]

A process map of ICE’s oversight mechanism for solitary confinement, as described in the GAO report, can be seen in Graphic 1, below.[34]

Documentation of Noncompliance and Abuse

Despite these directives, whistleblowers and government investigators alike have documented the abuse and overuse of solitary confinement in immigration detention over the past decade, particularly among vulnerable groups such as people with mental health conditions, physical disabilities, LGBTQ+ people, and survivors of torture and domestic violence.[35] Oversight mechanisms have also been repeatedly flagged as failing to ensure compliance.[36] Indeed, current Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas has been on notice about these failures related to solitary confinement since 2014.[37] The OIG, which provides independent oversight of DHS, has expressed concern about ICE’s repeated failure to follow its own directives limiting the use of solitary confinement.[38] In a 2021 audit, OIG reiterated those concerns while flagging ongoing problems with complying with reporting requirements and record retention policies related to “segregation.”[39] Recognizing that solitary confinement can result in severe negative psychological effects, particularly for people with preexisting mental health conditions or people at risk of suicide, OIG also concluded that ICE had failed to document whether it properly considered alternatives before placing someone in “segregation.”[40]

Similarly, a 2022 report from the GAO again highlighted that ICE did not consider alternatives to “segregation” for most placements.[41]

Recent Developments and Persistent Failures

In September 2023, the Department of Homeland Security’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL) and the DHS Office of General Counsel issued a memorandum documenting more than 60 complaints over the past four years regarding people with serious mental health conditions or a mental health disability held in solitary confinement in ICE custody across the country.[42] The seven examples provided in the memorandum reflected a range of issues, including immigrants held in solitary confinement while on suicide watch and with diagnoses such as chronic PTSD, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.[43] The memorandum also revealed that immigrants were reluctant to report suicidal ideation and mental health concerns because they feared being placed in solitary confinement.[44] According to the complaints, immigrants were often left without access to psychiatric medication, access to counsel or legal visits, or the ability to send or receive mail while in solitary confinement.[45]

These concerns are longstanding. In 2012, PHR, in partnership with the National Immigrant Justice Center, published a report on solitary confinement in ICE detention, “Invisible in Isolation: The Use of Segregation and Solitary Confinement in Immigration Detention.”[46] That report demonstrated how solitary confinement of people in ICE custody was applied arbitrarily, inadequately monitored, harmful to health, and a violation of their due process rights.

Between 2012 and 2014, experts submitted reports to DHS’s Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties documenting deaths of people detained in solitary confinement, where the deceased had presented signs of mental illness, ranging from depression to schizophrenia. Despite having special vulnerabilities, they were nevertheless subjected to solitary confinement without consideration of more appropriate care or medication.[47]

Over 10 years later, little has changed. Recent complaints filed by advocates continue to highlight the arbitrary and excessive use of solitary confinement in immigration detention. In a Colorado facility, for example, advocates documented escalating misuse of solitary confinement, including its use as a retaliatory threat. One person was placed in solitary confinement more than 10 different times for reasons ranging from eating “too slowly” and speaking “too loudly” to having suicidal thoughts and being upset about deportation.[48]

Methodology and Limitations

A two-pronged approach guided the data collection for this report. First, faculty and students at HLS collected and analyzed data that they obtained from ICE and other federal agencies, including through litigation under FOIA. This data included reports, excel spreadsheets, e-mails and other documents from ICE and other federal agencies concerning the use of solitary confinement in immigration detention. Second, HMS faculty and students conducted qualitative, structured interviews with formerly detained immigrants who had experienced solitary confinement. While the aim with the ICE data was to generate aggregate statistics on people detained in solitary confinement in facilities nationwide, the goal of the interviews was to explore personal experiences in confinement.

ICE FOIA Data Analysis

With some limited exceptions, FOIA requires federal agencies like ICE to disclose previously unpublished or unreleased information pursuant to public records requests. In November 2017, HIRCP submitted FOIA requests to several federal agencies, including ICE, to obtain previously unpublished communications, records, training materials, evaluation reports, and memorandums documenting ICE’s use of solitary confinement in detention facilities.

After the agencies failed to adequately respond to these requests, HIRCP successfully sued ICE and other federal agencies in federal court. In July 2023, the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts ordered ICE to respond to many of HIRCP’s requests.[49] In October 2023 – six years after HLS filed its original FOIA requests – ICE finally produced records detailing its use and misuse of solitary confinement in immigration detention.

ICE uses the SRMS to track solitary confinement placements. HIRCP received a redacted SRMS spreadsheet from ICE detailing, among other things, the reasons for placing people in solitary confinement, the dates those people were placed in solitary confinement, the duration they were held in solitary confinement, and the names of facilities that placed people in solitary confinement.[50] The spreadsheet is similar to records obtained by POGO and ICIJ,[51]but the information obtained by HIRCP includes more recent data on solitary confinement placements with release dates between September 4, 2018 and September 13, 2023. This data came from 125 facilities throughout the United States that are run by or contract with ICE.[52]

HLS faculty and students analyzed the data using Microsoft Excel and Stata to determine the average length of time that people were held in solitary confinement as well as the total number of solitary confinement placements. Further analysis was conducted to compare this data across years and facilities. Additionally, HLS assessed some of the reasons listed for why immigrants were placed in solitary confinement. The code and data to reproduce these analyses are available online at Harvard Dataverse, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AT7YFA.

HLS faculty and students also reviewed several ICE quarterly reports as well as medical expert reports commissioned by CRCL that were produced in response to the FOIA litigation.[53] The medical expert reports focused on assessing mental health conditions of people detained, as well as assessing mental health resources at the Henderson Detention Center, Nevada; Etowah County Detention Center, Alabama; Clinton County Correctional Facility, Pennsylvania; and Houston Contract Detention Center, Texas.[54]

Despite the significant disclosures obtained through the FOIA process and litigation, several limitations restricted HIRCP’s analysis. By the time of this report, ICE had still not released all the data the district court ordered it to produce.

Limitations of FOIA Data Analysis

ICE has consistently provided inaccurate information about the use of solitary confinement in immigration detention facilities via its SRMS. Firstly, the SRMS data documented far fewer placements of people in solitary confinement than calculated by the OIG in its 2021 report, in which OIG obtained records directly from detention facilities for a sample of 474 individual “segregation” placements from fiscal years 2015 to 2019.[55] Specifically, the SRMS dataset for these chosen placements lacked about 16 percent of the solitary confinement placement records that the detention centers reported for the same time period.[56]

Second, comparing ICE’s SRMS data with vulnerable population data trackers, a 2022 report from the GAO revealed underreporting.[57] To reach this conclusion, GAO compared data produced by ICE to available vulnerable population data trackers and found serious discrepancies with the SRMS data.[58] For instance, it found that only about 76 percent of people with a mental health condition and only about 12 percent of the people with a serious mental health condition were actually reported by SRMS.[59]

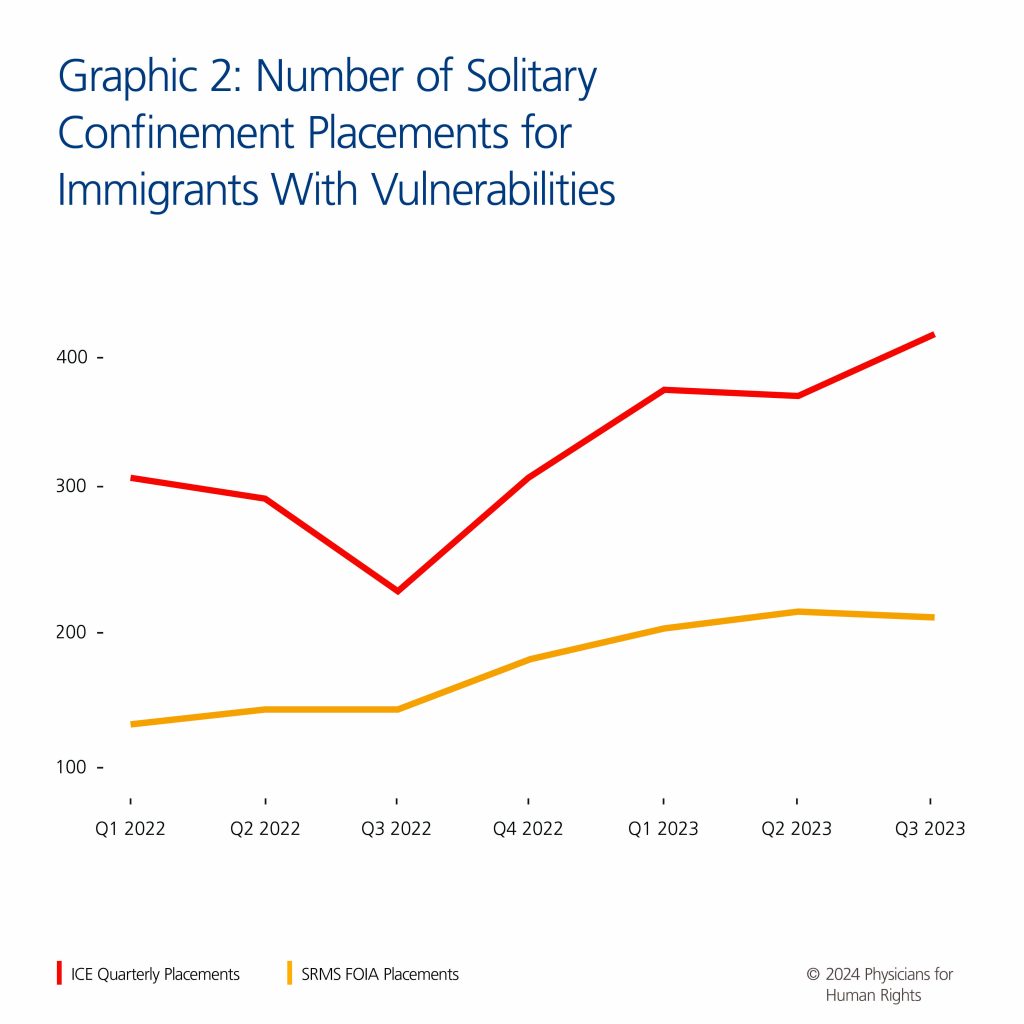

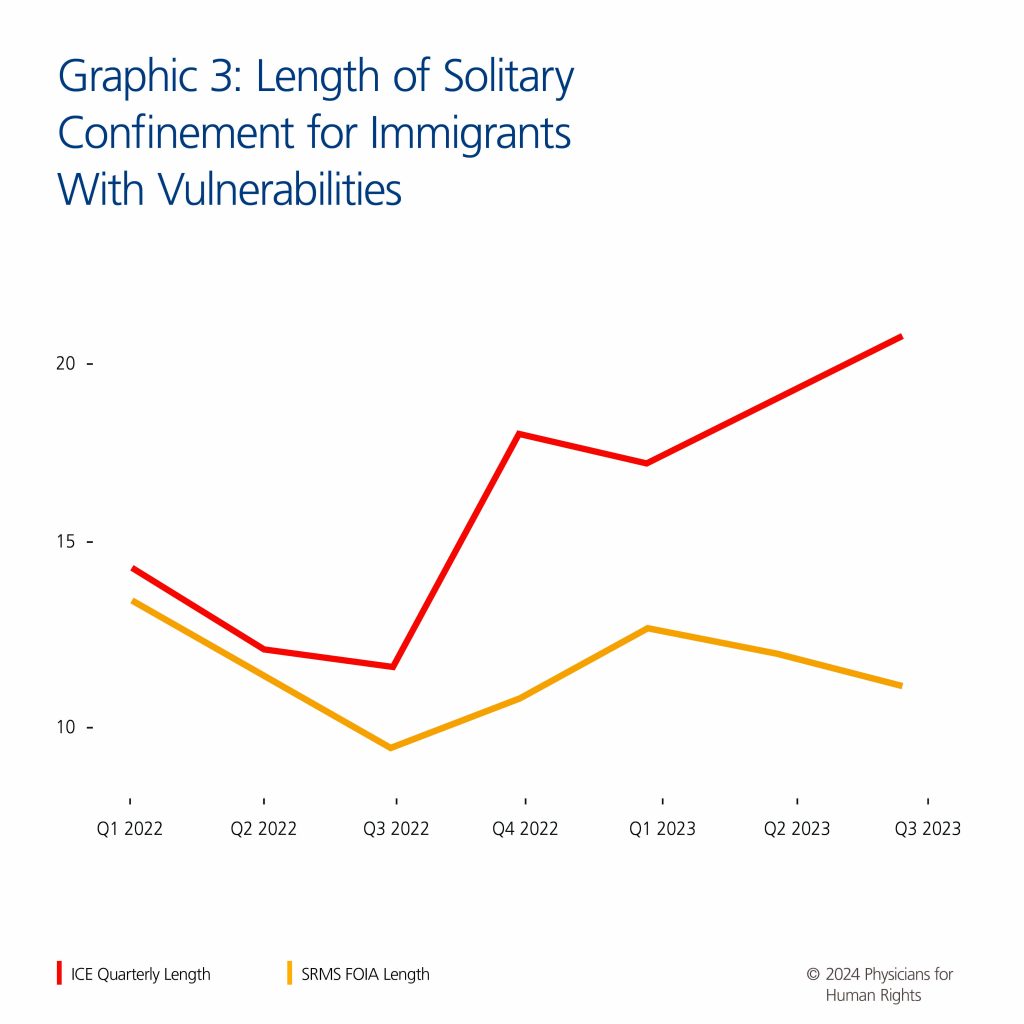

Inconsistencies with SRMS data continue as data that ICE has only made publicly available for 2022 and 2023 reflects. Comparisons between publicly published quarterly ICE aggregate statistics from 2022 and 2023[60] and data HLS obtained through FOIA litigation[61] revealed a substantial underreporting in the number of placements and length of solitary confinement of vulnerable populations reflected in the FOIA SRMS data.[62] According to the publicly available ICE data, there are up to twice as many placements of vulnerable immigrants in solitary confinement during 2022 and 2023 than reflected in the FOIA SRMS data.[63] In addition, the publicly available ICE data for 2022 and 2023 show that the number of placements of vulnerable immigrants in solitary confinement is increasing at a faster rate than the number reflected in the FOIA-obtained SRMS data.[64]

Similarly, the average length of time in solitary confinement of vulnerable immigrants was much longer in ICE’s publicly available quarterly statistics than reflected in the FOIA SRMS data. With an increasing trend, the duration of solitary confinement ranged from one to 10 days longer in the ICE publicly available reports than the FOIA-obtained estimates.[65] These publicly available quarterly aggregates of vulnerable populations suggest a strong possibility of longer solitary confinement durations for people with mental illnesses than this report shows.

Lastly, CRCL evaluations also revealed that immigration facilities misrepresented their use of solitary confinement.[66] One CRCL evaluator encountered an “especially disturbing” incidence of misreporting at the Houston Contract Detention Facility in 2014.[67] Though ICE policy requires staff to offer programs in a comparable fashion to detained persons in administrative “segregation” and those in the general population – and the staff at the Houston facility actively assured the evaluator that they had complied with this – the evaluator reported that “none of this turned out to be true.”[68] The evaluator found that immigrants in administrative “segregation” were denied access to programs, shackled, and locked in their cells for approximately 22 hours a day.[69] The staff’s offering of misinformation “compromised the integrity of [the] facility review.”[70] Without accurate ICE reporting, other immigrants may similarly suffer in silence. Due to a combination of these issues, this report may in fact underrepresent the total number of immigrants placed in solitary confinement, their mental statuses, and their durations in confinement.

Structured Interviews with Formerly Detained People

From March 6 to August 17, 2023, the HMS research team conducted 26 interviews with people formerly detained in immigration detention using a standardized questionnaire developed by the research team. All study participants were 18 years of age or older, had been released from immigration detention, and had experienced at least one period of solitary confinement during detention in the United States after September 4, 2013. This date corresponds to the day in which the ICE “Segregation Directive” was published that ordered limits on the usage of solitary confinement in detention centers and contained a pledge to “ensure the health, safety, and welfare of detainees in segregated housing.”[71] All interviews were conducted by WhatsApp or standard telephone call, in languages in which participants were fluent (English or Spanish). While the study was open to speakers of any language, all participants spoke either fluent English or Spanish, so no outside interpreters were necessary. Interviews lasted approximately one hour. Participation was voluntary, and all participants provided verbal informed consent to participate in the study. A $40 electronic gift card was offered to participants as reimbursement of a standard meal and phone minutes. This study was reviewed by the HMS Institutional Review Board and determined to be exempt from further review. The study was also reviewed and approved by PHR’s Ethical Review Board.

Structured interviews were based on a questionnaire (see Appendix A) that was designed to assess the implementation of ICE’s National Detention Standards (NDS) (Version 2.0, 2019).[72],[73] The questionnaire included three sections: 1) Demographics; 2) Solitary Confinement Conditions; and 3) Solitary Confinement Experiences. The data collected during the interviews were both quantitative and qualitative in nature. All quantitative data were statistically analyzed in Excel (Version 16.40).

Participant Recruitment

Participants were recruited through outreach to immigration attorneys. Attorneys were asked to present information about the study to clients released from immigration detention who met inclusion criteria using a standardized script and flyer. Additionally, participants were able to refer other potential study participants.

Attorneys and participants were notified that this study did not include a language restriction. All referral information was placed into an anonymous, secure REDCap referral form. Referral information included the participant’s phone number, time availability, preferred language, and preferred mode of contact (WhatsApp or telephone). Names of participants were not requested or collected via the referral form to ensure anonymity and protect participants. Thirty-two potential participants were referred to the study and contacted by research staff. Six referred persons either decided not to participate or were unable to be reached to schedule the interview. Twenty-six people participated in the study and completed the entire questionnaire verbally. All participants accepted the electronic gift card.

Human Subjects Protections

Most participants were contacted through WhatsApp, which provides end-to-end encryption. For participants who did not have or prefer WhatsApp, a regular telephone line was used to conduct the interview. Prior to initiating the interview, the consent form was verbally reviewed with participants in its entirety, and verbal consent was obtained. Written consent forms in participants’ preferred language were also sent prior to the interview or offered. Participants were assured that their interview was confidential, that no identifying information would be collected, and that none of their responses would be communicated to their attorney or affect their pending immigration case (if they had one – many had already been deported). During the interview, quantitative and qualitative data was collected in real time in a secure REDCap database. No identifying information was collected or stored. Participant information (including the participant’s phone number) was collected in a separate REDCap database that could not be linked to participants’ survey responses. Finally, participants who accepted the electronic gift card for participation were sent the electronic gift card through WhatsApp, short message services, or, if preferred, e-mail. Any e-mail communication with lawyers and participants was conducted through a Harvard Medical School delegated-access e-mail account used exclusively by study staff, and all correspondence was deleted 30 days after completion of the study. The study staff’s WhatsApp accounts used to contact participants and conduct the interviews were also cleared of correspondence data after completion of all interviews.

Limitations of the Interview Study

The data presented in the report represent the reported experiences of 26 people held in immigration detention in a limited number of facilities across the United States. Given the study’s modest sample size, we do not capture the full range of experiences of ICE-detained people experiencing solitary confinement in the United States. Additionally, some facilities were only known to the participants by their state location rather than the city, so it was not possible to know how many distinct facilities were represented. The interview portion of this study may also suffer from sampling bias in that attorneys may have only referred specific participants whom they felt would be comfortable participating. Participants sometimes referred friends they had made while in detention together, representing additional sampling bias. Although this study did not include a language restriction, lawyers may have been more likely to refer clients with whom they could communicate more easily without the use of an interpreter. This data was also subject to potential recall bias, as responses were based on participant memory of detention conditions. There was potential for variation in interview style among interviewers, but care was taken to minimize this variability through extensive interviewer training before and during the study period and by including at least two staff members per interview (one interviewer, one recorder) for each interviewer’s first interview. The use of a structured questionnaire with consistent wording was designed to reduce interviewer bias. Prior to publication, the authors of this report had the opportunity to present the findings to key personnel in DHS and ICE.

Key Findings

View from Government Records

Immigration Detention Facilities Used Solitary Confinement Extensively

One of ICE’s directives recognizes that the use of solitary confinement “is a serious step that requires careful consideration of alternatives” and calls on facilities to limit their use of solitary confinement only to situations where it is “necessary.”[74] Despite this standard, ICE documented well over 14,000 solitary confinement placements in the past five years alone.[75] These placements lasted 27 days on average, well in excess of the 15-day period that constitutes torture, as defined by the Special Rapporteur on Torture. Indeed, with a median length of confinement of 15 days, nearly half of the recorded placements exceeded 15 days and many placements lasted far longer: 682 solitary confinement placements lasted at least 90 days, while 42 lasted over a year.[76] In almost 30 percent of solitary confinement placements lasting over 90 days and 25 percent of placements lasting over 365 days, the people placed in solitary confinement suffered from a mental health condition.[77]

Additionally, the FOIA data reveal numerous egregious examples of facilities holding people in solitary confinement for years at time:[78]

- Just under two years (727 days) (Denver Contract Detention Facility, CO)

- Over a year and a half (759 and 567 days) (Otay Mesa Detention Center, CA)

- Over a year and a half (652 days) (Buffalo Service Processing Center, NY)

- Over a year and a half (637, 559, and 550 days) (Northwest ICE Processing Center, WA)

- Just under a year and a half (526 days) (Eloy Federal Contract Facility, AZ)

Strikingly, for-profit corporations operate all five of the facilities with the longest periods of detention.[79]

The Northwest ICE Processing Center also had one of the highest (ninth out of 125) average lengths of solitary confinement stays on record (average length at this location was 55 days).[80] Conditions at the Denver Contract Detention Facility were also poor overall: the average length of stay at this facility between 2018 and 2023 was 52 days.[81] The American Immigration Council and other groups have documented the repeated misuse of solitary confinement at the Denver facility and in July 2023 filed an administrative complaint with DHS’s Office of Inspector General, CRCL, Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman, and ICE’s Office of Professional Responsibility.[82]

Data Spanning Several Years Shows No Improvement

In every year between 2019 and 2022, there were several thousand new solitary confinement placements (between 2,000 and 3,300), reported in immigration detention.[83] As of September 2023, there were already 2,301 reported placements.[84] In light of the recent uptick in immigration enforcement,[85] and assuming a similar number of new solitary confinement placements in each of the remaining four months of 2023, the total number of placements in solitary confinement for 2023 likely surpassed 3,000 people.

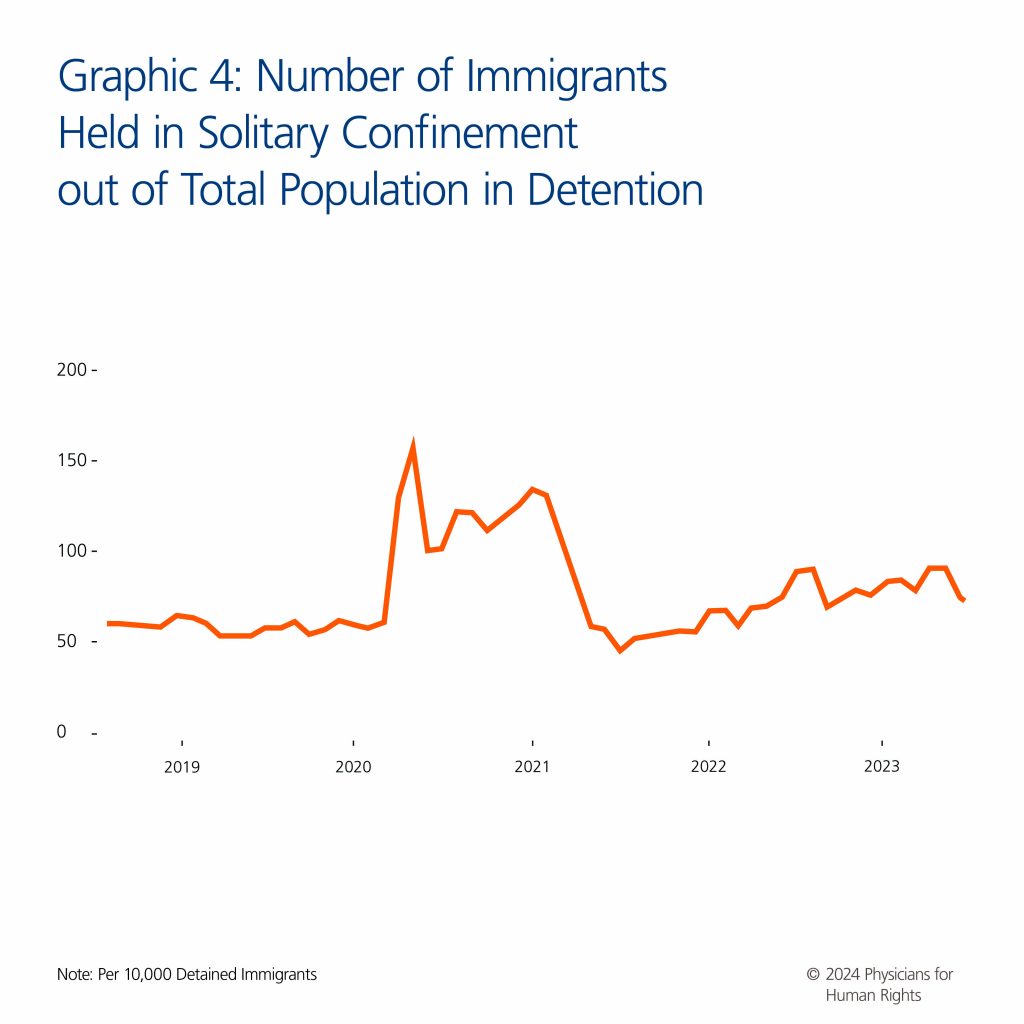

The proportion of people in solitary confinement in ICE, out of the total number of those in ICE detention overall, has varied over time.[86] This number spiked in 2020 in conjunction with COVID-19 because immigration detention facilities used “solitary confinement under the guise of medical isolation.”[87] While the number of people held in solitary confinement has declined from its peak in 2020, there has generally been an upward trend in the percent of people detained who are held in solitary confinement since its lowest point in mid-2021.[88]

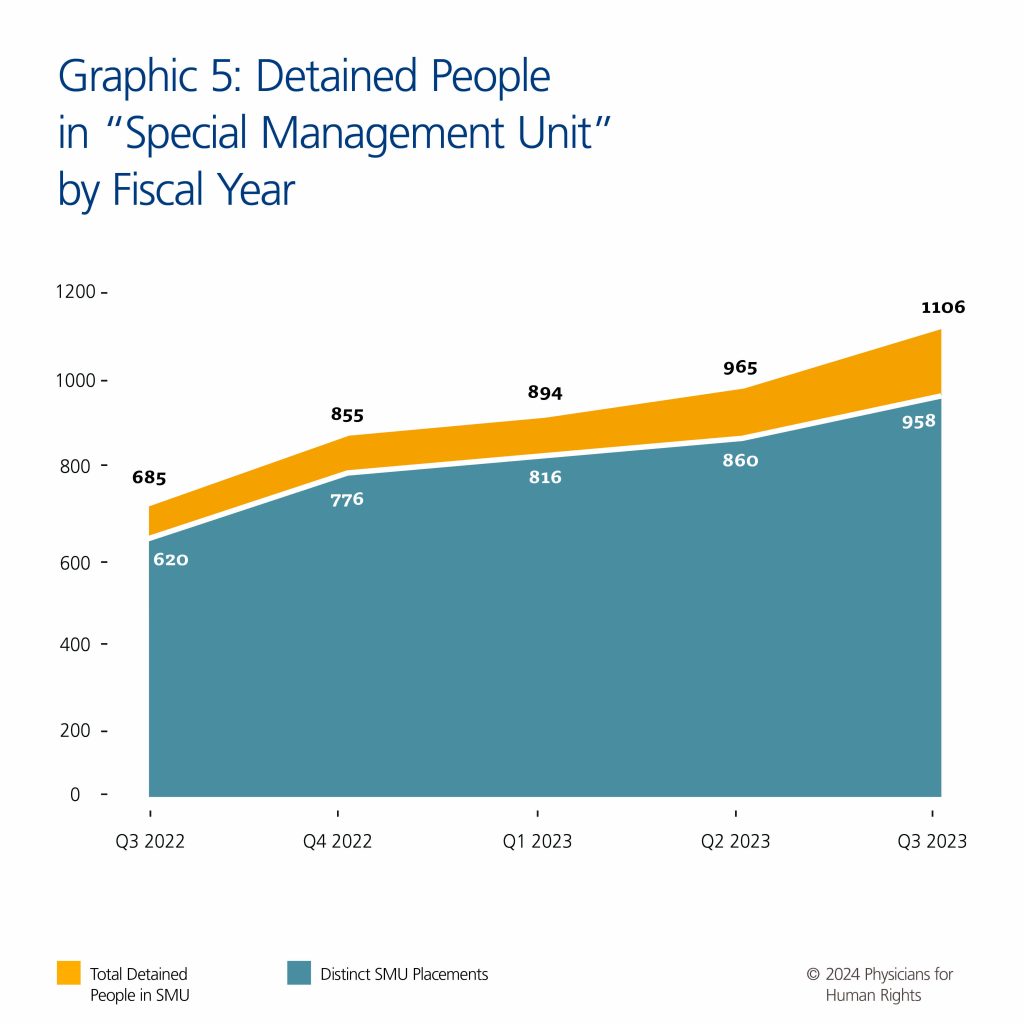

*ICE released this graph of 2023’s third quarter solitary confinement statistics on October 16, 2023.

According to ICE’s own quarterly reports, there were 1,106 solitary confinement placements in the third quarter of 2023.[89] This represents a 14.6 percent increase from the previous quarter, and a 61 percent increase from a year ago, based on the most recent data that ICE had released at the time this report was written.[90]

Also, the average length of solitary confinement placements remained well above 15 days in each of the past five years.[91] For 2023, this average was already at 23 days by September.[92] The average length of placements was 65 days for people who were placed in solitary confinement but were not released by the date ICE produced the SRMS data. As it is unknown when and if they were released, this is an underestimate.

Solitary Confinement Used Arbitrarily and as Punishment

Immigration detention facilities are authorized to use solitary confinement only as a last resort.[93] Yet facilities often placed immigrants in solitary confinement to punish minor disciplinary infractions. For example, FOIA documents indicate that on at least one occasion an immigrant was placed in solitary confinement for 29 days for “using profanity” and two immigrants were placed in solitary confinement for 30 days because of a “consensual kiss.”[94] In another record, ICE documented that an immigrant was placed in solitary confinement for 38 days because they “refused to get out of bunk during count.”[95]

This pattern of arbitrary solitary confinement placement is reflected in the administrative complaint filed regarding the Denver Contract Facility, where the facility put one person in solitary confinement for “eating too slowly.”[96] This same person faced solitary confinement 10 more times, for similarly groundless reasons: “If I climbed on top of a table to get a guard’s attention, solitary [confinement]. If I had suicidal thoughts, solitary [confinement]. When the guards would tease me about being deported back to my home country and make airplane sounds at me and gesture like a plane was taking me away, I would become upset and then get solitary [confinement] for being upset.”[97]

In other cases, immigration detention facilities appear to have deliberately discriminated against immigrants identifying as transgender.[98] In 2014, a CRCL evaluation of the Houston Contract Detention Facility found multiple incidents of facility discrimination against transgender immigrants.[99] The evaluator stated that transgender immigrants were disproportionately subjected to security measures typically used for immigrants placed in solitary confinement for aggressive behavior, such as “lock-down in their cells[,] use of cuffs for movement within the facility [and] inability to attend groups available to general population inmates.”[100] CRCL further noted that this treatment can “cause mental trauma and distress that resulted in avoidable suffering, depression, and suicidality.”[101] The FOIA data included 62 detainees that were placed in confinement for the following reason: Protective Custody: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender (LGBT). The average length of stay for these detainees was 57 days, with a median of 34 and maximum of 286 days. In addition, a recent ICE report with quarterly statistics on solitary confinement reveals that the number of transgender immigrants in solitary confinement more than doubled (increased by 114 percent) in the third quarter of 2023, the most recent quarter of available data shared by ICE.[102]

Unsafe Detention Facility Conditions Exacerbated the Misuse of Solitary Confinement

Immigration detention facilities often placed people in solitary confinement to purportedly address issues such as overcrowding and threats to harm staff and/or other people in detention. In 2016, a facility put one person in administrative “segregation” “due to no available [bed] space” elsewhere in the detention center.[103] The facility’s staff left this person in administrative solitary confinement for 372 consecutive days because she requested to remain there “due to being afraid of being around other detainees.” Yet she was diagnosed by the facility psychologist as having multiple severe mental health conditions: PTSD and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD).[104] Though this person was not the only person to request solitary confinement in detention, solitary confinement is not an appropriate solution to a lack of safety among the general detention center population.

When people requested solitary confinement or facilities put them in it for other non-disciplinary reasons, they have been unable to “make any legal calls, have legal visits, [and] have access to [their] legal documents.”[105] Solitary confinement under the guise of protection can also be life-threatening. In one person’s words, “[the staff] told me solitary kept me safe and helped me, but it was only ever a punishment . . . I have tried to kill myself three times already because of this endless nightmare and the consistent torture of solitary confinement.”[106] Another person felt that the stress of returning to solitary confinement was “too much for him to bear,” and he also attempted suicide.[107]

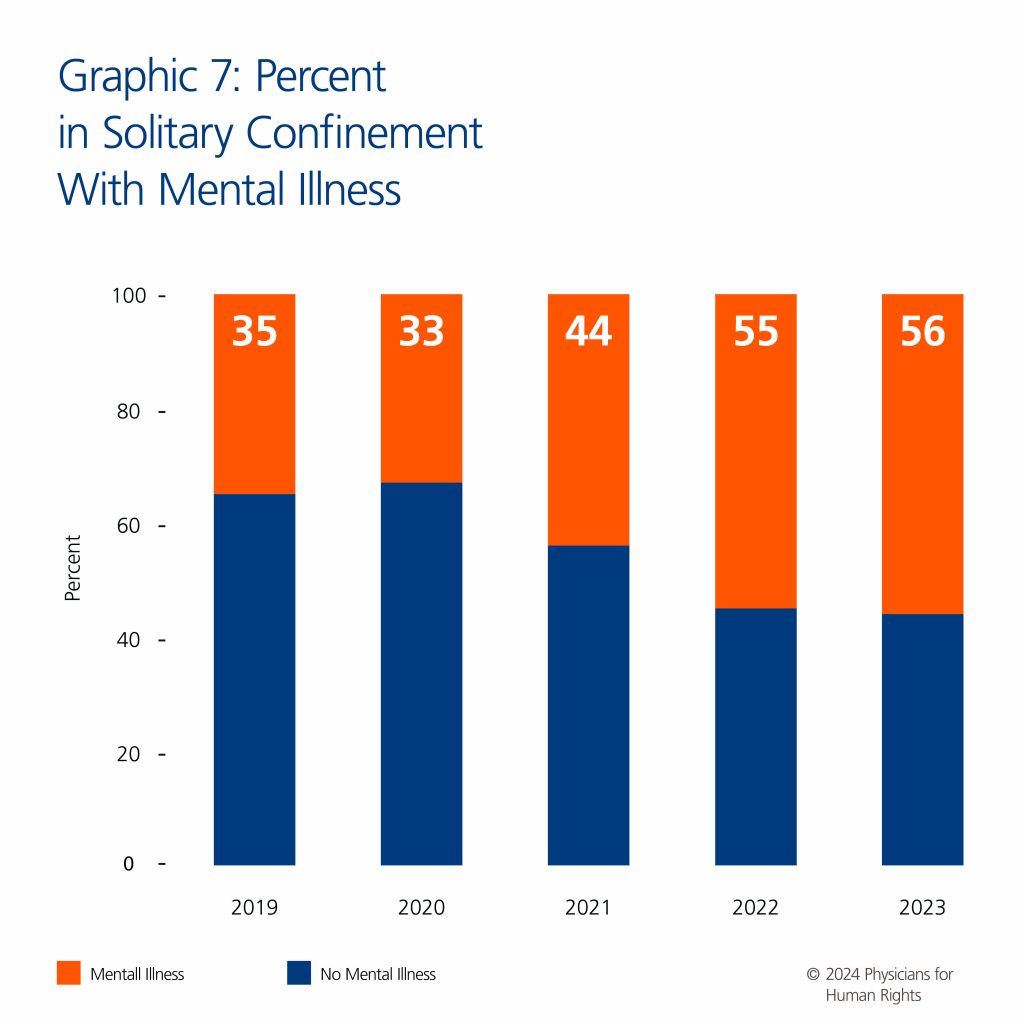

People with Mental Health Conditions Unfairly Discriminated Against

According to the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, people with mental health conditions should not be held in solitary confinement.[108] ICE’s 2013 “Segregation Directive” mandates that its facilities must not place vulnerable populations in solitary confinement unless as a “last resort.”[109] Yet many of the people placed in solitary confinement in immigration detention between 2018 and 2023 had documented mental health conditions and it was unclear what alternatives, if any, to solitary confinement were considered.[110] Among the 8,788 records for this period where ICE’s SRMS reported the mental health status of immigrants in solitary confinement, over 40 percent had documented mental health conditions.[111] In the redacted SRMS spreadsheet produced in the FOIA production,[112] ICE reported immigrants’ mental health status in only 62 percent of its total solitary confinement records. Based on multiple findings of discrepancies with SRMS data,[113] the actual number of immigrants with mental health conditions who were placed in solitary confinement between 2018 and 2023 could be much higher.

The percentage of immigrants with mental health conditions placed in solitary confinement jumped from 35 percent in 2019 to 56 percent in 2023.[114] Additionally, while SRMS reported that 20 percent of the solitary confinement placement records for immigrants with mental illnesses in 2019 involved an immigrant with a serious mental health condition, close to 27 percent of immigrants with mental health conditions in solitary confinement in 2023 were classified as suffering from a serious mental health condition.[115] Among people whom SRMS labeled as suffering from a mental health condition, the average length of stay in solitary confinement was approximately 23 days; however, the average length in solitary for detained persons suffering from a serious mental health condition was 33 days.[116]

Some of the facilities with highest average confinement lengths for immigrants with mental health conditions included the Richwood Correctional Center (LA), Denver Contract Detention Facility (CO), Yuba County Jail (CA), Otay Mesa Detention Center (CA), and Henderson Detention Center (NV).[117] The average length of solitary confinement for immigrants with mental health conditions at these facilities ranged from three to six months.[118]

Immigration detention facilities also likely violated the 2022 ICE directive related to the treatment of immigrants with serious mental health conditions by denying immigrants with mental health conditions the “necessary and appropriate treatment and monitoring” that the directive requires.[119] For example, the 2023 CRCL memorandum reported how one immigrant was placed in solitary confinement even though they suffered from MDD, bipolar disorder, PTSD, and schizoaffective disorder or psychosis; their placement in solitary confinement caused “the delay or discontinuation of important mental health medications.”[120]

Immigration detention facilities also used mental health conditions as a justification for placing immigrants in solitary confinement despite the well-known negative effects of solitary confinement.[121] In one record, ICE reported that a “[s]ubject was placed in protective custody after he was not able to properly care for himself in general population. Subject has been diagnosed with schizophrenia.”[122] This person was held in solitary confinement for 56 days.[123] In another instance, an individual with a mental health condition was held in solitary confinement for 28 days because they reportedly responded to officers with “irrational answers” and were observed making “unusual body movements.”[124]

Substandard Medical Care in ICE Custody Caused Severe Health Consequences

ICE’s failure to ensure adequate medical resources in detention centers created life-threatening conditions for immigrants in solitary confinement. CRCL reported that between 2012 and 2014, some facilities left immigrants without any meaningful access to a mental health professional.[125] In least at one facility, mental health professionals stopped working altogether.[126] Another facility had nursing staff without psychiatric training performing suicide risk assessments, staff giving medications to immigrants without their consent, and medical forms lacking immigrants’ past medical histories.[127] These conditions can acutely impact immigrants in solitary confinement.[128] For instance, one of CRCL’s evaluations reported that an immigrant was “[u]nable to sleep” and “starting to have hallucinations due to being locked in cell all the time.”[129] This immigrant stated that his depression was “getting worse day-by-day.”[130]

Immigration facilities also punished suicidal immigrants with solitary confinement.[131] At one facility evaluated by CRCL in 2012, facility staff “actively discourage[d] [suicidal] detainees from seeking help.”[132] This hostile environment was created by staff that forced suicidal immigrants to undress except for a safety smock and remain in solitary confinement without access to counseling until they denied their “current suicidal thought[s]”.[133] These procedures humiliated and punished immigrants in critical need of medical care.[134]

In Their Own Words: Interview Findings of Experiences in ICE Solitary Confinement

Participant Demographics

Twenty-six participants were interviewed (questionnaire provided in Appendix A) in total; 23 identified as male (88 percent), and one each identified as female, agender, and transgender man (4 percent each). Interviewee ages ranged from 29 to 56 years old (average 36.2 years). Participants were originally from 19 different countries, including 31 percent who were from Mexico, 23 percent from Colombia, and 12 percent from Honduras. Eight percent of the people were multilingual, comfortably speaking more than one language. Thirty-one percent of the participants felt “uncomfortable” or “very uncomfortable” speaking English and would have very likely required translation services while in detention to easily communicate with non-bilingual staff members. A comprehensive list of countries of origin and languages spoken by participants is included in Appendix B.

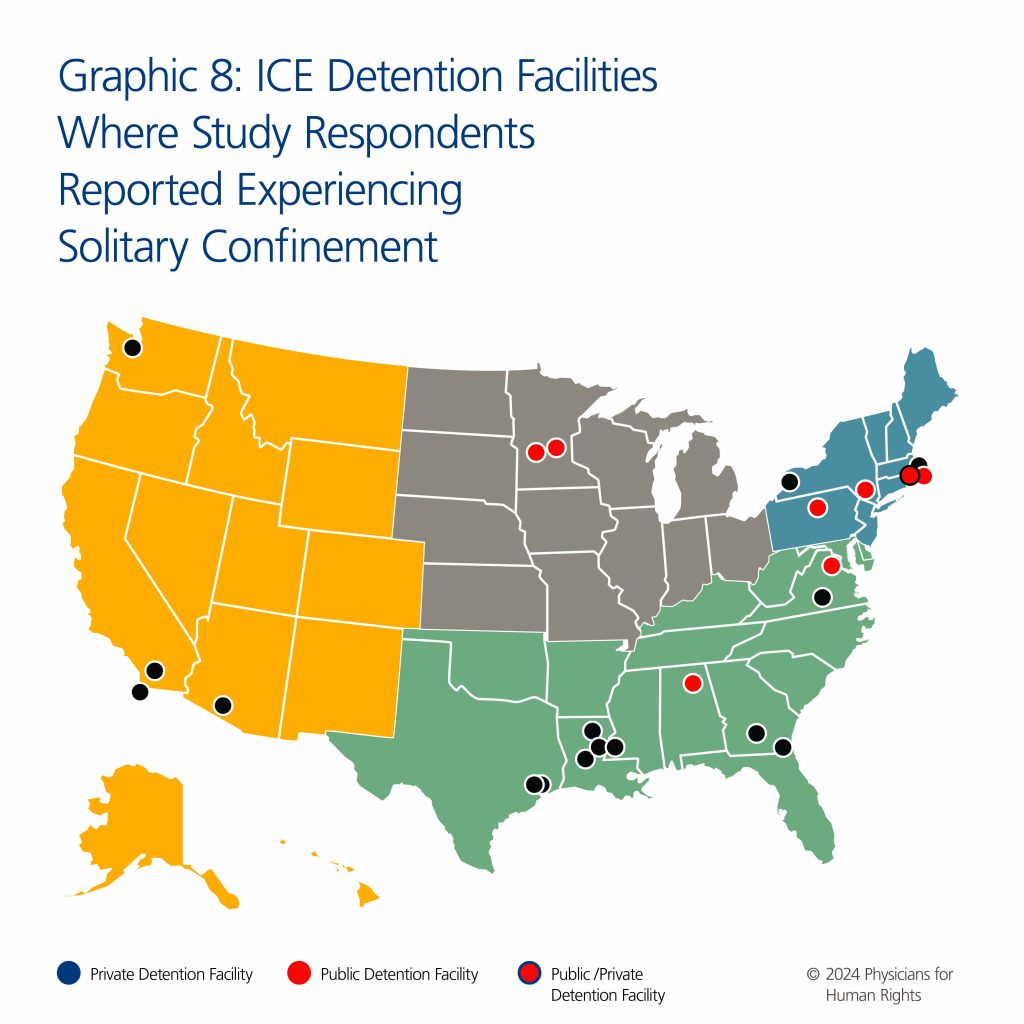

These 26 participants were detained in at least 34 unique detention facilities in the United States – representing 11 county/public facilities, 22 private facilities, and one mixed-status facility – across 17 different states. Some participants could not recall the exact name or city of the facility in which they were held, so this list is not exhaustive of the locations where interviewees were detained and/or experienced solitary confinement. Of the private facilities, 12 were run by GEO Group, five by CoreCivic, and one facility each by Ahtna Support and Training Services, Immigration Centers of America, LaSalle Corrections, and Valley Metro Barbosa Group. One location, the Donald W. Wyatt Detention Facility, is publicly owned but privately operated. Of the 34 identified facilities, people experienced solitary confinement in 23 of them (68 percent).

Misuse of Solitary Confinement

Spending up to a Year in Solitary Confinement

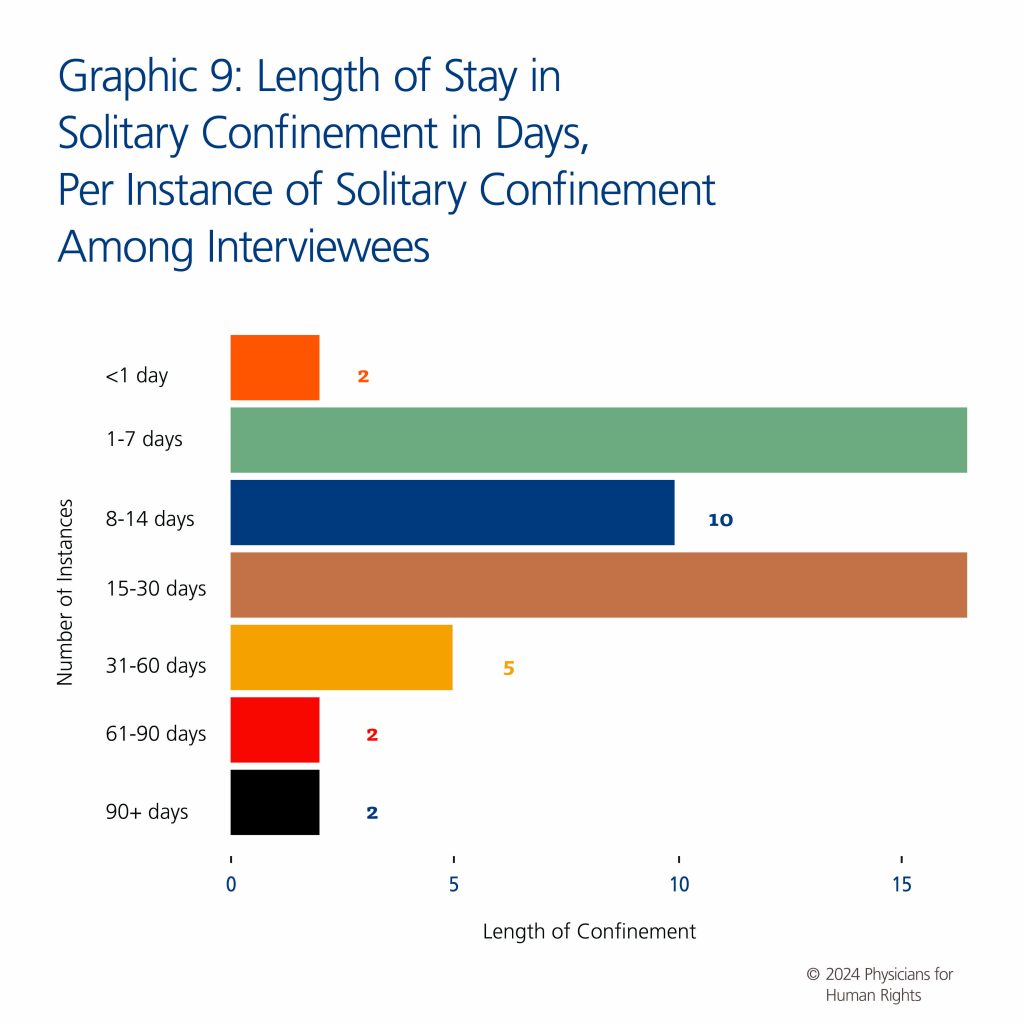

Interviewees experienced an average of 3.6 separate stays in solitary confinement (range 1–30 stays). Each stay lasted an average of 32.2 days, with a median of 14 days. This is nearly six days longer than the average confinement in “segregation,” as seen in the FOIA data between 2018 and 2023. There was substantial variation in how long detained persons stayed in solitary confinement, as seen in Graphic 9.

Out of 55 described distinct placements in solitary confinement, a majority (61 percent) lasted longer than 14 days (what ICE defines as “extended segregation”), and 37 percent were greater than a month. One person stated that they were in solitary confinement for more than a year (32-year-old agender person, Etowah County Jail).

Solitary Confinement Was Often Misused as Punishment

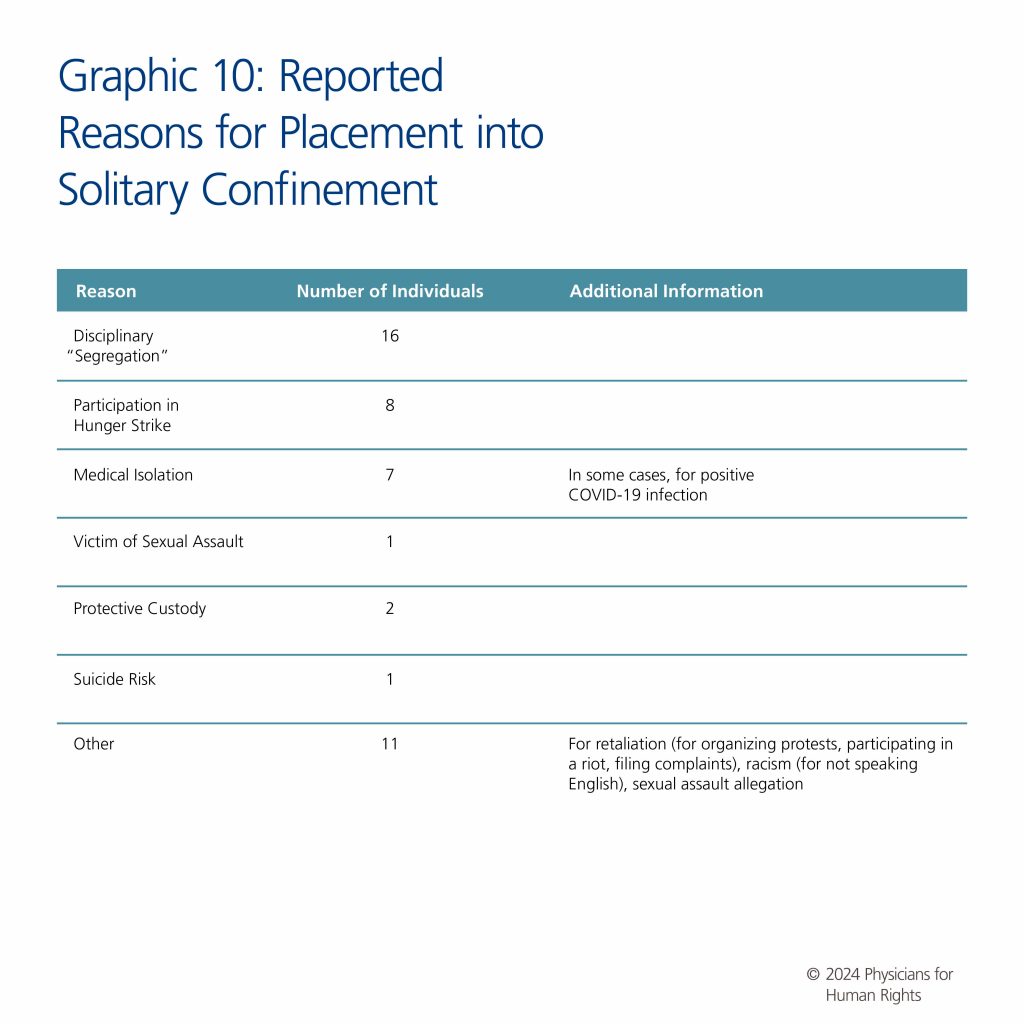

The most commonly reported reason for solitary confinement placement was disciplinary “segregation” (n=16, 62 percent) (Graphic 10). ICE’s standards explicitly state that disciplinary “segregation” can only be used after receiving “a hearing in which the detainee has been found to have committed a prohibited act and only when alternative dispositions would inadequately regulate the detainee’s behavior.”[135] However, only seven (44 percent) of those placed for disciplinary reasons received an official hearing for disciplinary “segregation.” The majority did not receive this due process. One person reported that intimidation was used to dissuade him from having hearings. Instead, he was encouraged to plead guilty to the charges, because, contrary to guidance and directives, he was told that if he went to a hearing, “they would often double the punishment or the time. So instead of 10 days, suddenly you would get 20–30 days” (30-year-old man, Kandiyohi County Jail).

“If you don’t listen to their rules, that’s a reason to go to the hole. If you don’t do anything they ask you, that’s a reason to go to the hole.”

35-year-old man, Caroline Detention Facility

Accounts from study participants conflicted frequently with the regulations as outlined in the aforementioned ICE “Segregation Directives.” Solitary confinement was commonly used to punish people who submitted complaints, organized protests, or required medical isolation. For instance, eight people (31 percent) reported being put in solitary confinement after participating in a hunger strike.

The decision to place someone in solitary confinement often relied on the discretion of correctional officers, leading to instances where detained persons were placed in solitary confinement as a punitive measure despite not having done something that would warrant disciplinary “segregation.” One participant shared that he was assaulted by one of the officers in the facility, which led to chest pain. He then tried to relay his medical concern: “I had chest pain [from the assault] but the correctional officer said I was lying so they put me in solitary confinement” (34-year-old man, Bristol County Correctional Facility). Solitary confinement was also abused for minor offenses, such as taking food from the cafeteria to their rooms. One respondent who spent nearly his entire time in detention inside of solitary confinement stated, “I would go on a walk without a uniform and that was enough to be put in solitary [confinement]. For any minimal thing, they would find an excuse to put me in solitary [confinement]. Even to use the stove to heat up coffee, they gave me 7days of solitary [confinement]” (37-year-old man, Orange County Jail).

One interviewee reported a common understanding that people exhibiting symptoms of serious mental health conditions would be placed in solitary confinement instead of being connected to care. One participant said he saw people placed in straitjackets and thought of solitary confinement as where “mentally and psychologically unstable” people were placed (32-year-old man, Richwood Correctional Center).

A Lack of Transparency

When people were put into solitary confinement, there was often uncertainty regarding how long their stay would last. Thirteen people (50 percent of interviewees) were never given an estimate of how long they were going to stay in solitary confinement, and if they were, this estimate would often change. One participant stated, “when you go to ‘the hole’ [solitary confinement] you don’t know how long you are going to be there.” (39-year-old man, Eloy Detention Center). Study participants noted that officials exploited loopholes to keep detained persons in solitary confinement longer, through either enforcing multiple separate solitary confinement stays or transferring persons in solitary confinement between facilities. “They just kept me there until they transferred me, because by the policy you can’t keep people for more than 2 weeks in solitary [confinement],” said one participant, “So when I complained about it, they just transferred me.” (33-year-old man, Caroline Detention Facility).

“They give you a paper saying what they say happened. If you don’t agree, they put you in longer.”

31-year-old man, Bristol County Correctional Facility

According to various directives, those in disciplinary “segregation” should have received reviews every seven days. However, only nine people (35 percent) remember being interviewed by a supervisor and only 14 people (54 percent) received a written review of why they were placed in solitary confinement. This suggests that there was a lack of transparency with people in solitary confinement, who may have had only brief interactions with supervisors overseeing their solitary confinement stay and did not have clear communication regarding this process.

Concrete Beds and 24/7 Lights Were Commonplace

Being placed in solitary confinement meant experiencing substantially worse living conditions than those in the general population at those same facilities. While specific descriptions of each cell differed, almost every participant described minimal furniture, uncomfortable bedding, small room sizes, and small windows. Eleven people (42 percent) reported having worse mattresses and bedding in solitary confinement compared to those issued in the rest of the detention facility. Specifically, seven people reported bedding was of poorer quality or described having no mattress at all, noting that the “bed was made out of cement with no cushion, only a blanket” (29-year-old man, unknown center in Louisiana) or just steel surfaces.

Interviewees described a lack of autonomy over basic control of their living conditions. One participant described how “the correctional officer (CO) had control of the light and flushing of the toilet; [I] had to bang the door and say ‘CO, bathroom! or CO, light!’”(34-year-old man, Bristol County Correctional Facility).

“The light is on 24 hours a day… the guards wouldn’t dim or turn them off at times… we went crazy, we tried to cover those lights with paper.”

30-year-old woman, Irwin County Detention Center

ICE standards require that all “cells and rooms used for purposes of “segregation” must be well-ventilated, adequately lit, appropriately heated/cooled, and maintained in a sanitary condition at all times, consistent with safety and security.”[136] Despite these specifications, the lighting and temperatures of the rooms were controlled by the facility staff to create uncomfortable living conditions, leading to sleep deprivation and disorientation as to the time of day. For example, several people described the temperature in the rooms as being unbearably cold, with the air conditioner on at all times and not being provided blankets or jackets if they asked.

One person stated, “I lost all sense of time – lights were on all the time and there were no clocks on the walls or windows” (32-year-old man, Richwood Correctional Center). Twenty people (77 percent of interviewees) described having fluorescent lights in their room that were turned on either 24 hours per day or for prolonged periods, such as from five in the morning until midnight.

Keeping lights on for prolonged periods of time is known to cause sleep deprivation through dysregulation of the body’s natural sleep–wake cycles, or circadian rhythm, and may lead to cognitive disorganization, paranoia, and hallucinations.[137] These conditions included social isolation, constant bright lighting, and cold exposure are well-documented strategies for torture and interrogation designed to inflict psychological distress and have been described in immigration detention settings in the United States.[138]

Smaller and Worse Meals in Solitary Confinement

ICE’s own standards state that while in detention, people should be given “nutritious, attractively presented meals” and that “food rations shall not be reduced or changed or used as a disciplinary tool.”[139]

However, eight people (31 percent) reported that their meals in solitary confinement were worse than those served to the general population. Three people said that the portions were smaller than usual – even half the size of normal. Although most participants reported being served three meals a day, three people reported that the facility sometimes only provided two meals (breakfast and dinner) a day to them while in solitary confinement. When one participant asked for water, he was told “to drink water from the toilet” (37-year-old man, Orange County Jail).

Meals could also be of such poor quality that the food was inedible, because it was either expired or unappetizing, such as resembling “vomit”(32-year-old agender person, Etowah County Jail) or “soggy tuna on bread” that looked like “cat food” (29-year-old man, unknown center in Louisiana).

Dietary restrictions for various medical conditions or religious exemptions were not always accommodated. One interviewee with food allergies said that he “told the kitchen [about the allergy], they told me to talk to the doctor. Then the doctor told me to talk to the kitchen. I couldn’t eat anything for months. I’m allergic to the turkey, I’m allergic to basically everything. So, I didn’t eat most of the time in there.”(41-year-old man, Golden State Annex). Another participant shared that, “I asked for a halal meal and the correctional officer was like ‘when you want to eat good food, go back to Africa.’ He said, ‘if you don’t eat this, I’m not giving you no food.’ But that’s my right to eat halal meals.”(34-year-old man, Bristol County Correctional Facility).

Access to Communication and Services

Restricted Legal and Personal Communications

While people were held in solitary confinement, all communication outside of the detention center was closely monitored and restricted. Seven people (27 percent of the participants) were never able to call anyone on the telephone while in solitary confinement, and eight people (31 percent) could not write or receive letters. The remaining interviewees often had significant limitations on who they could talk to, even facing cases where “they blocked every number on my phone. It got to the point where I was only able to talk to my attorney”(38-year-old man, Montgomery Processing Center). These constraints meant that sometimes people could not let their loved ones know that they were in solitary confinement. There were also time limitations (as brief as five minutes per call), prohibitive costs (video calls cost $3 a minute), and sparse access to phones (sharing one telephone between 20 to 40 cells). Five people also said that their calls were monitored and recorded – especially calls to their lawyers or to the press – and that they could have their connections cut if they were heard discussing the living conditions inside detention or other complaints. The majority (65 percent) of participants also experienced staff violating their privacy by not keeping mail private, One in particular cited that facility staff would “open and read your letters and decide whether or not to send them; or keep them there”(34-year-old man, Bristol County Correctional Center).

“If I ever told my wife about mistreatment during a phone call or showed my wife the living conditions during a video call they would end my call immediately.”

50-year-old man, Northwest ICE Processing Center

These restrictions on people’s ability to communicate with the outside world also prevented interviewees from relaying information to their legal teams. Several people reported that the times they had to access the phone were at night, and they [facility staff]“only let me out after work hours so I couldn’t get in contact with anybody” (33-year-old man, LaSalle Processing Center). Even though the National Detention Standards (NDS) maintain that detainees in SMU (Special Management Unit) “may not be denied legal visitation,” people reported variable access to their lawyers.[140] While some people could see their legal team once a week, others could only reach them on the phone and faced significant barriers to receiving legal advice.

Limited Access to Recreation, Hygiene, and Religious Services

Interviewees described frequent limitations to recreation and hygiene instituted as punitive measures. Even when these rights to participate in recreation and religious events were explicitly protected in ICE’s NDS guidelines,[141] people reported being unable to do so while in solitary confinement.

People in solitary confinement should be offered at least “one hour of recreation per day … at least five days a week.”[142] While the remaining 23 hours were spent confined inside the cell, this one hour a day represented the only time people had to shower, talk on the phone, and use the recreational facilities. Seven people (27 percent) “rarely” or “never” received this much recreational time in solitary confinement. In these cases, the detained persons should have received a form of written correspondence about why and for how long their recreation was to be suspended.[143] Yet no interviewees received any such notice.

The NDS say that people in solitary confinement can “shower at least three times weekly” to maintain their personal hygiene.[144] A majority (73 percent) of participants could shower between three to seven times a week; however, seven (27 percent) could only shower twice a week or never. For some in solitary confinement, showering was only allowed during their limited designated recreation time, forcing them to make difficult decisions about if they should allocate their time to shower or talk to others on the telephone.

While in detention, people are reliant on the commissary to purchase basic necessities such as soap, shampoo, and deodorant. However, 15 people (58 percent) were not able to use the commissary while in “segregation” at all.

Finally, although the NDS state that persons in solitary confinement “shall be permitted to participate in religious practices” unless there is an explicit safety concern,[145] most people reported that they were not allowed to leave the cell to attend religious services and their requests to join were denied. A majority of participants (16 people; 62 percent) reported never being able to participate in religious practices while in solitary confinement. Two interviewed persons reported that they faced discrimination as Muslims: there were no specialized Islamic services, and the Qur’an was only available for purchase at exorbitant prices whereas the Bible was provided for free.

Medical Health Care in Solitary

Lack of Regular Medical Assessments in Solitary

“When you’re in solitary [confinement], you don’t get to see any doctors, nurses, dentists, anything .… There would have to be something really wrong with you .… But usually you don’t see any doctors, or nurses, dentists, or anything when you’re in seg.”

30-year-old man, Kandiyohi County Jail

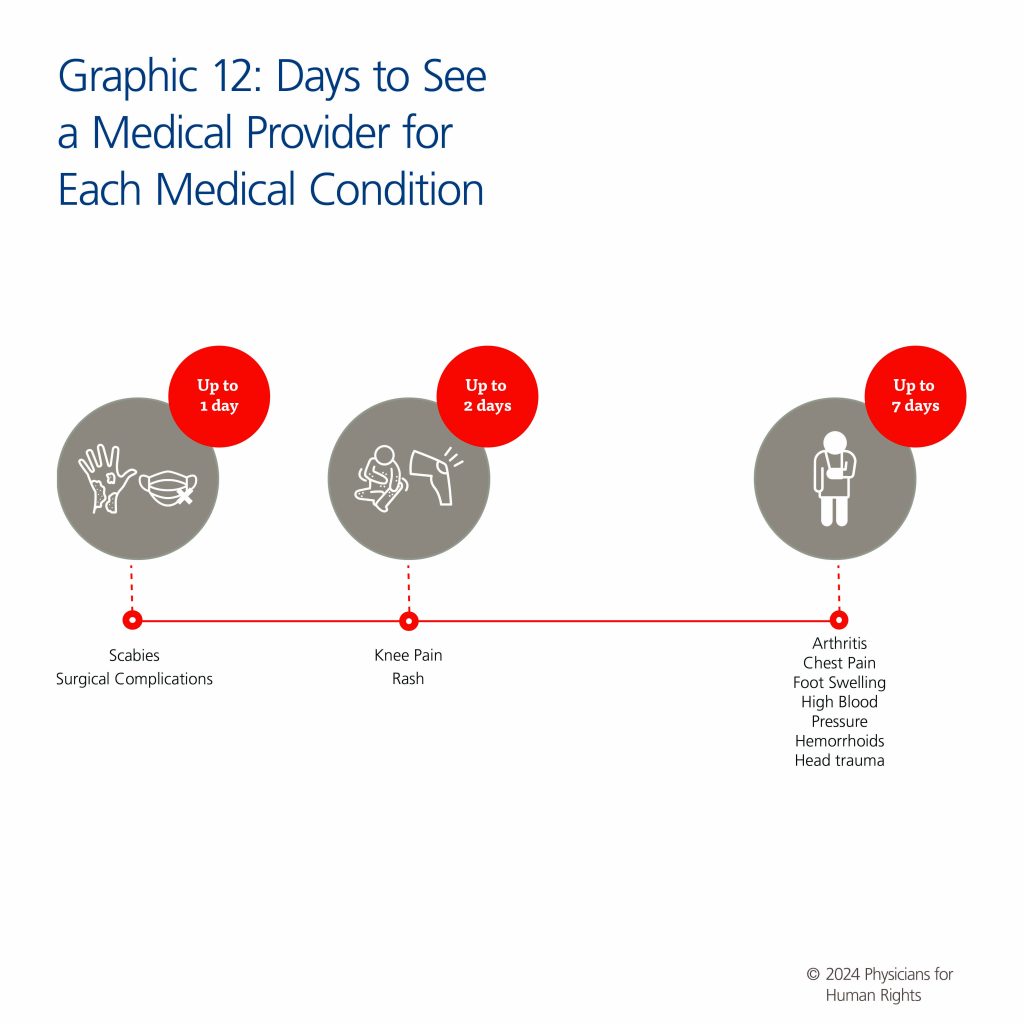

Many interviewees had significant medical needs requiring attention during solitary confinement. Fifteen people (58 percent of interviewees) had a medical condition requiring care during solitary confinement, and 12 people had new medical conditions arising while in solitary confinement. Examples of these medical conditions and the time passed before seeing a provider are listed in Graphic 12 below.

ICE regulations outline that “[d]etainees must be evaluated by a health care professional prior to placement in an SMU (or when that is infeasible, as soon as possible and no later than within 24 hours of placement).”[146] Yet, of the 26 participants included in this study, only 11 people (42 percent) reported being seen by a medical professional before being placed in solitary confinement and only nine people (35 percent) were screened for preexisting mental health conditions.

In addition to the initial assessment, there should also be frequent “face-to-face medical assessments at least once daily for detainees.”[147] However, only 13 people (50 percent of the study’s respondents) remembered being routinely evaluated by a health care provider. Only those participating in hunger strikes or who were deemed suicide risks were consistently seen by a health care professional daily. Otherwise, the frequency with which people were seen by a health care professional varied from daily (four people) to approximately every three to four days for those in medical isolation (two people). Others, even those with chronic or acute medical conditions, were seen either intermittently or not at all over the duration of their confinement. Many recounted that it felt like staff were just going through the motions to fulfill detention center requirements and documentation.

Interviewees reported difficulty identifying the role of various health care professionals who interacted with them, suggesting that interactions were either unduly brief or that staff members failed to appropriately clarify their role during their care. As one person described, “[Health care professionals] come around, they make their rounds. But if you want to talk to them, you got to stop them. You got to be up at a particular time … Because they come by at 5, 6 in the morning. Otherwise you miss them” (38-year-old man, Montgomery Processing Center). When participants were able to identify the types of health care professionals, the majority (56 percent) reported being seen by a nurse, with a minority being seen by physicians, physician assistants, therapists, psychologists, or medical assistants. Multiple respondents reported that nurses were the primary health care providers in these facilities; doctors were either reserved for more serious concerns or entirely unavailable. One interviewee raised concerns about the licensure of health care staff employed by the detention center, relaying reports that the doctor where he was detained had had his license suspended.

Long Waits and No Medications

Of the 14 people who submitted requests to see a medical provider, only three people (21 percent) reported being seen within 48 hours. Of the remaining cases, eight (57.1 percent) waited one week or more to be seen. Notably, these cases included potentially serious complaints such as chest pain, lower extremity swelling, and head trauma. Despite placing multiple requests for conditions including migraines, insomnia, and dental pain, three people were never medically evaluated while in solitary confinement.