Executive Summary

For the last two years, the Trump administration’s Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), or “Remain in Mexico” policy, have forced almost 70,000 people seeking asylum in the United States to wait in dangerous Mexican border towns while their cases pend – in violation of U.S. and international law, which prohibits returning asylum seekers to places where they fear that they may be persecuted. With the indefinite postponement of immigration hearings due to COVID-19, asylum seekers in MPP face ever-lengthening periods of stay in Mexico, where many have experienced violence, trauma, and human rights abuses.

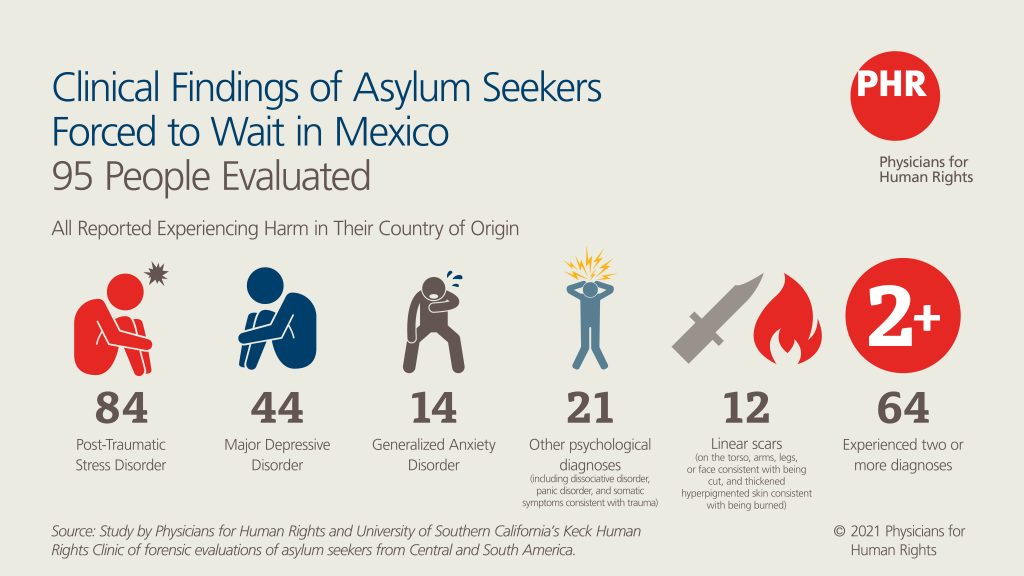

Since the start of MPP, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) has responded to more than 100 requests by attorneys for pro bono forensic evaluations of asylum seekers enrolled in the program, most in support of asylum claims and a few in support of requests for MPP exemption due to health issues. To quantify the extent of reported health and human rights violations affecting asylum seekers in MPP, PHR partnered with the University of Southern California’s Keck Human Rights Clinic (KHRC) to review 95 deidentified affidavits based on forensic evaluations of asylum seekers from Central and South America ranging in age from 4 to 67 years. We found that at least 11 people belonged to categories that should have been exempt from MPP enrollment. Although most affidavits focused on the harms migrants fled in their home countries, most documented compounding harms to the migrants after they were returned to Mexico under MPP, including physical violence, sexual violence, kidnapping, theft, extortion, threats, and harm to family members. The affidavits also reported unsanitary and unsafe living conditions, poor access to services, family separations, and poor treatment in U.S. immigration detention. Nearly all of those evaluated were diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, and many exhibited other debilitating psychological conditions or symptoms.

This study adds to the considerable evidence that it is not safe for migrants to remain in Mexico while their U.S. asylum cases are pending, and forcing them to do so violates U.S. and international law. The incoming Biden administration should immediately admit all people enrolled in MPP into community settings in the United States, rescind MPP, and initiate an investigation to determine appropriate redress for people harmed by this policy.

Introduction

The Trump administration introduced the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP),[1] or “Remain in Mexico” policy regarding asylum seekers on January 29, 2019, in San Diego, California, and in subsequent months expanded the policy[2] along the border to the Mexican locations of Ciudad Juárez, Matamoros, Mexicali, Nogales, Nuevo Laredo, Piedras Negras, and Tijuana. To date, the policy has forced at least 69,333[3] people seeking asylum in the United States to remain in Mexico while their asylum cases were being decided in U.S. immigration courts, a process that likely would take months or years even without delays due to the pandemic. The policy has left migrants trapped in Mexican border cities and states where they are targeted for violence and persecution while waiting for their asylum hearings in courts across the U.S. border.

This policy is currently being challenged in U.S. courts as a violation of U.S. immigration law, administrative law, and international human rights law, which prohibits returning people to places where they fear persecution. Although one federal appeals court has decided[4] that the policy is unlawful, to date the Supreme Court has allowed the policy to proceed,[5] relying on assurances from the U.S. government that asylum seekers will be safe in Mexico – which is supposed to provide visas and work permits – and that other policy calculations outweigh the risks. But, to date, those affected by this policy have not been “safe” in any way that the government represented to the court. As of December 15, 2020, there have been at least 1,314 public reports[6] of rape, kidnapping, torture, and other violent attacks against asylum seekers and migrants returned to Mexico under MPP.

For more than 30 years, members of the Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) Asylum Network,[7] comprising 1,900 volunteer health professionals, have conducted pro bono forensic evaluations for asylum seekers involved in U.S. immigration proceedings. These evaluations – conducted in accordance with the principles and methods of the Istanbul Protocol,[8] the UN manual for documenting and investigating torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment – are generally requested by attorneys, who identify a need for trained clinicians to assess the consistency of a client’s physical and psychological signs and symptoms with the client’s account of alleged torture or persecution. PHR partners with 21 medical school asylum clinics around the country, including with the University of Southern California’s Keck Human Rights Clinic (KHRC), a student-run organization that connects asylum seekers and their legal representation with volunteer clinicians trained to provide forensic medical examinations.

PHR and KHRC assessed forensic evaluations conducted for asylum seekers enrolled in MPP in order to quantify the extent of reported health and human rights violations affecting those subjected to the policy. Most of these evaluations were requested in support of the client’s asylum claim, or for other forms of relief if they were ineligible for asylum; several were requested by legal counsel as part of the application for humanitarian parole or for the client to be removed from MPP based on likelihood of persecution or torture in Mexico.

Background

As of December 2020, although the U.S. government had sent 69,333 asylum seekers to Mexico under MPP, there were only 22,777[9] pending cases because many asylum seekers have given up their cases. There have been many factors contributing to this, especially the dangers faced in Mexican border towns. Asylum seekers face the daunting reality that, to date, only 615 people enrolled in the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) (just over one percent) have been granted asylum[10] or another form of relief since the program was initiated. This stands in contrast with a fiscal year 2018 nationwide asylum grant rate of 35 percent.[11] Asylum seekers have limited access to attorneys in Mexico, with just seven percent having legal counsel.[12] With the closure of immigration courts and postponement of immigration hearings due to COVID-19, scheduled proceedings have been delayed, subjecting asylum seekers to nearly indefinite periods of stay in Mexico.

Homicide rates in Mexican border states[13] are at their highest in decades. Criminal cartels often target migrants with kidnappings, beatings, and murders,[14] due to migrants’ perceived vulnerability and potential U.S. contacts who might be extorted for ransoms. There have been multiple reports of unsafe and unsanitary living situations,[15] as well as the dangerous[16] conditions many migrants are subjected to when living along the border. MPP has created a humanitarian crisis, strained the capacity of Mexican shelters and social services, and created overcrowded and unsafe conditions for migrants. The pandemic made it even more difficult for migrants to find work or to obtain essential services, with one Tijuana non-profit coordinator describing conditions as “a living hell.”[17] Infectious diseases were already a danger in crowded shelters and camps; since the pandemic, public health services[18] have been restricted to Mexican citizens, while migrants must pay cash for private medical care, including for childbirth, pediatric vaccines, and other essential health care. Exposure to extreme weather conditions, lack of clean water and food, and poor sanitation have further increased health risks,[19] especially during the pandemic.

Methodology

Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and Keck Human Rights Clinic (KHRC) conducted a content analysis of 95 affidavits written by experienced clinicians performing medical-legal evaluations of migrants seeking asylum in the United States who were part of the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) program. Since the introduction of the MPP policy, PHR has responded to 116 requests from attorneys representing people enrolled in MPP. Affidavit narratives include a description of harms experienced by family members when relevant, but the exam and diagnosis in each evaluation focused on the individual client. Although a few of these evaluations were conducted during visits of clinicians to the border, the majority were conducted remotely, first as a way to increase the capacity to provide evaluations and then due to pandemic-induced travel restrictions. PHR requested the deidentified forensic asylum affidavits of these clients, receiving 82 affidavits, which were stored in a password-protected folder only accessible to two PHR staff. KHRC similarly responded to 13 requests from attorneys for clients living in Tijuana and stored the deidentified affidavits on a protected server. PHR staff and KHRC researchers (two medical students and one resident, supervised by an attending physician) shared the affidavits through a secure OneDrive folder which was only accessible to the researchers for the period of time needed for coding.

All researchers used a secure Qualtrics database in order to extract the data. The Qualtrics survey form was developed jointly by the researchers based on previous experience with asylum seekers enrolled in MPP.

Researchers chose a content analysis methodology[20] to analyze the data set in order to quantify and count types of trauma experiences of asylum seekers enrolled in MPP. The researchers’ detailed knowledge and experience with MPP clients over the past two years enabled them to pre-define a set of content categories for coding. These included demographics, harm experienced in their country of origin, harm experienced in Mexico, and their diagnoses and health and mental health issues. This was mainly done through multi-check boxes to aid analysis. The form also contained a number of free text boxes to capture any themes which emerged outside of these categories as well as notable quotes from the affidavits.

Qualitative analysis of asylum affidavits was approved by both the University of Southern California Social Behavioral Institutional Review Board and the Physicians for Human Rights Ethics Review Board.

Several limitations of this study must be noted. First, the narratives were obtained by clinicians who did not use a structured or standardized form to collect the information as part of forensic evaluations. As a result, the type of information at times can vary between evaluators, meaning that the data set is not uniform. Further, this is not a representative sample of all people enrolled in MPP but is rather an intensity sample of people enrolled in MPP who were referred for physical or psychological evaluations. It is possible, therefore, that this is a group with higher needs or a more pronounced history of trauma. This review is also based on the narratives of a self-selected group which includes only people who had legal representation, thus not representative of the majority of those under MPP, who do not have legal representation. Finally, 111 of the placed cases were conducted to support asylum claims and four to support requests to be exempt from MPP due to known physical or mental health issues; one more was for both asylum and MPP exemption. The primary aim of many medical-legal affidavits was to examine physical and psychological harms caused by experiences of persecution in the migrants’ home countries for their ongoing asylum case, rather than their experiences in MPP for the purpose of a non-refoulement interview,[21] a fear-assessment interview[22] to determine whether it is likely that a person will be tortured or persecuted if returned to Mexico while their case is pending. Thus, our findings may underestimate harm migrants experienced while in MPP, resulting in undercounting of the findings where they are tangential to the main purpose of the affidavit.

Findings

Demographics of Interviewees

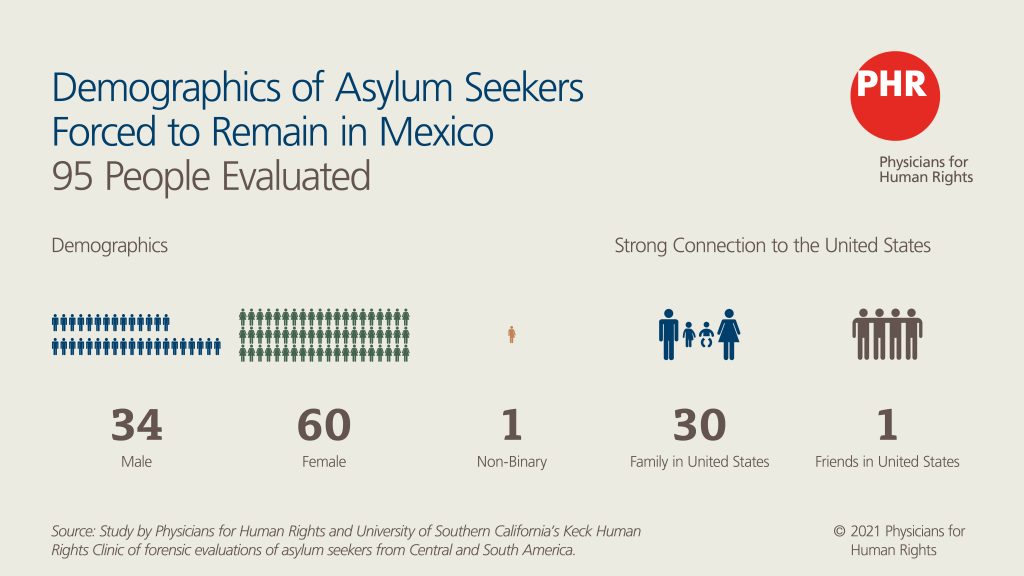

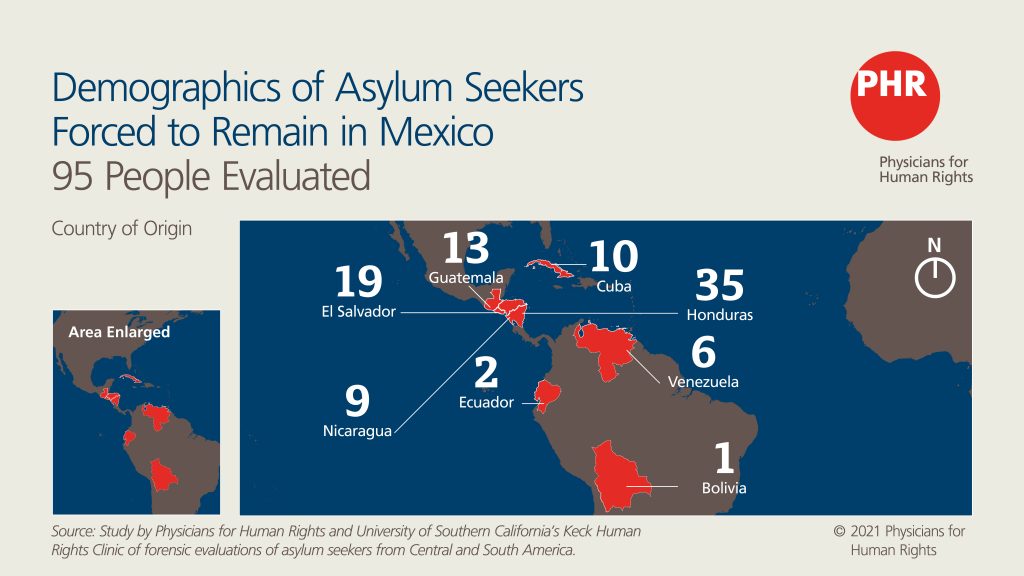

Of the 95 asylum seekers who were evaluated, 34 were male, 60 were female, and one was non-binary. Their ages ranged from 4 to 67 years old, with the mean and median ages both 29. Eighteen were children, 12 under the age of 12. They came from eight different countries: Honduras (35), El Salvador (19), Guatemala (13), Cuba (10), Nicaragua (9), Venezuela (6), Ecuador (2), and Bolivia (1). Eleven belonged to categories that should have been exempt from MPP enrollment, such as having severe known mental or physical health issues. Most of the people evaluated were residing in Matamoros (69), with some in Tijuana (13), Ciudad Juárez (3), Monterrey (2), Reynosa (2), and Nuevo Laredo (1). Thirty-one of the interviewees reported having strong connections in the United States, 30 of them with family and one with friends.

Reasons Asylum Seekers Fled Their Countries

Out of the 95 people evaluated, all reported experiencing harm in their country of origin. Eighty reported experiencing threats in their country of origin, including death threats. Sixty-six of the 95 experienced physical violence, 24 experienced sexual violence, 40 witnessed violence, 12 were kidnapped, and 24 experienced other forms of violence, such as incommunicado detention, extortion, land confiscation, and having family members or colleagues kidnapped, murdered, tortured, or raped. Some 83 of the respondents experienced two or more types of violence, 54 experienced three or more, and 10 people experienced four or more types of violence. Perpetrators were most commonly gang members (47). However, official state actors like police (22) and other government actors, including the military (25), also played a significant role in persecution. Family members (26) and community members (19) also inflicted harm. Forty-two people reported being harmed by two or more types of perpetrators. People reported that they were specifically targeted for a number of reasons, including being indigenous, LGBTQ or non-binary, HIV+, belonging to an opposition party, or participating in protests against government policies, as well as working as police officers who were resisting illegal orders or testifying against gang members, or being business owners who refused to pay extortion money to gangs.

Harms Experienced in Mexico

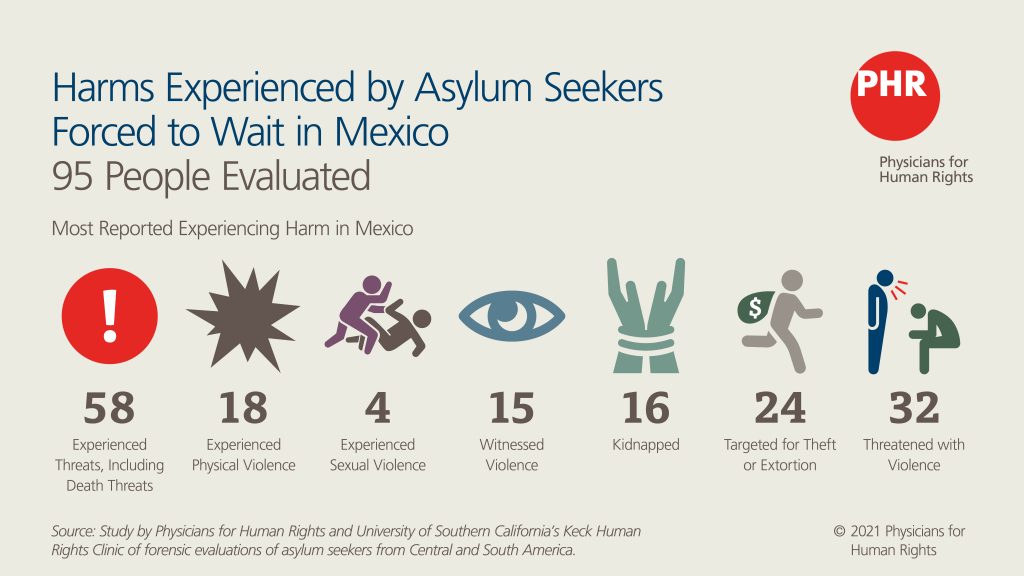

Out of the 95 people evaluated, 18 experienced physical violence, four experienced sexual violence, 15 witnessed violence, 16 were kidnapped, 24 were targeted for theft or extortion, and 32 were threatened with violence in Mexico. Fourteen reported that family members were harmed, including family members being beaten, robbed, kidnapped, molested, or sexually assaulted. Thirty-four of the respondents experienced two or more types of violence, 19 experienced three or more, and 10 people experienced four or more types of violence in Mexico. Perpetrators were most commonly gang members (19), but community members (17) and Mexican government actors, including police (8), were also reported as having harmed the asylum seekers in Mexico. Six people reported being harmed by two or more types of perpetrators, and others did not identify the perpetrator. Clinical evaluations did not always distinguish between harms which took place before or after the person was processed by the U.S. government and placed in the MPP program, because the evaluations primarily focused on the physical or psychological consequences of these traumatic events. Nevertheless, whether before or after enrollment in the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) program, the majority of asylum seekers evaluated by Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) (58 out of 95) experienced some form of harm in Mexico. These data indicate that Mexico is not providing safe conditions for migrants and that people waiting in Mexico while their asylum case is pending are likely to experience harm.

In one case, the asylum seeker was assaulted in the tent camp the night before the evaluation with the PHR psychologist, who observed that she was very distraught and experiencing physical pain during the evaluation, necessitating the interview to be cut short.

Many reported difficulty sleeping because of fear and sounds of potential dangers in the camp due to targeting of migrants in cartel territory. However, camps and shelters at least offer some level of protection. People reported to evaluators that they tried to limit their movement outside their tent or house in order to reduce their risk. A Cuban asylum seeker reported that he had to quit a job in Mexico which required late hours because he is afraid of being outside at night after being kidnapped in Mexico, and now he regularly experiences verbal abuse with derogatory slurs about his sexual orientation. Another LGBT asylum seeker who had been kidnapped in Mexico said that his kidnappers took his photo while he was kidnapped and threatened to use the photo to find him again; he has not reported the crime to Mexican officials out of fear for his life.

Even those who do not leave their home may still be targeted. As one clinician reported about an asylum seeker they evaluated:

“She and her son were kidnapped from a house in which they were staying [in Mexico]. Ms. K and her child were held captive, along with other migrants [for five days]. During that time, she was at times separated from the child, whom she was still nursing. During two of those days, she was raped by some of her captors and her child was forced to watch. She and her child were released only after her family paid a ransom. They had no shoes or belongings; the kidnappers had taken her money and her phone…. [Since release,] she has been getting harassing and threatening phone calls, which she believes are from her kidnappers and rapists, trying to force her into a sex ring. She is extremely afraid and does not leave the encampment.”

The length of stay in Mexico at the time of the evaluation was mentioned in 48 affidavits; at the time of the evaluations the mean duration of time in Mexico was seven months and the median was six months. MPP was introduced almost two years ago, but the majority of the evaluations in this study were conducted in Matamoros, where MPP was introduced later, and many evaluations took place in the first half of 2020. By the time of this report’s publication, the length of stay in Mexico would likely be much longer for these interviewees.

Family Separation Due to MPP

Family separations caused by MPP were a persistent theme. In some cases, parents and children were separated due to the dangerous conditions at the border. One child was kidnapped and taken from his mother by smugglers back to the United States as they crossed the border into Mexico; the mother told the PHR evaluator that she is considering drowning herself in the river if she is not granted asylum and reunited with her child in the United States. In other cases, knowing that unaccompanied children are exempt from the policy, parents described the pain of making the difficult decision to send their child back across the border alone to pursue asylum in the United States. One six-year-old was so traumatized by being kidnapped with his father after the two were sent back to Mexico that he lost half his body weight; as a result, his terrified father sent the boy to the U.S. border bridge so that he could find safety in the United States, where his mother lives. A young boy told his mother that he was so afraid of being sent back to El Salvador that he wanted to try to cross the border, although he had already heard multiple reports of other children drowning in similar attempts. Some U.S. border agents separated children from parents or guardians while enforcing MPP. One father was separated from his pregnant wife at the border when she was admitted to the United States and he was sent to Mexico; he has only seen his newborn son on video calls. A grandmother, the guardian for her six- and nine-year-old grandchildren, told the evaluator that she is constantly re-experiencing the trauma of being separated from them when she was sent to Mexico under MPP while they remained in the United States; she said she worries that her grandchildren will never be the same.

A Mother and Daughter, Separated and Traumatized Under MPP

Natalia* and her young daughter, Maria,* fled domestic and political violence in Central America, only to be subjected to MPP when they sought asylum at the U.S. border. Sent back to Mexico, they were abducted by a criminal organization. Natalia was abducted a second time while Maria hid herself in a stove.

The second time she was abducted, Natalia was separated from Maria and only later found out that her daughter had escaped to the United States, crossing the border as an unaccompanied child.

Of the first kidnapping, Maria states that:

“When we were heading to the store, three men with their faces covered placed a gun to my head and my mother’s head…. They would come and take my mother all the time. They would ask her to dress pretty and they would come get her. My mother would tell me not to scream or cry and just to hide when she was not there. She would ask me to cover my ears and my eyes as well.… I have a lot of nightmares in which I am taken from my mother’s side. I dream of people coming after me with guns and they kill me. I have an ongoing dream where I am in the park and I see two men coming after me and shooting me. I see my body filled with blood and, in the dream, I find myself running to a house in construction and hiding there scared while the men continue to search for me.”

At the time of their evaluations, Natalia and Maria were still separated. The evaluator in this case identified that both Natalia and Maria suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder and that Maria also suffers from depression; the evaluator stated that mother and daughter should be permitted to reunite in the United States, citing the significant, ongoing risk Natalia faces in Mexico as well as the destructive impact of family separation.[23]

* Names changed for security reasons.

Abuse by U.S. Officials

Some people reported poor treatment in U.S. immigration detention before they were returned to Mexico. People reported very cold temperatures, no changes for wet clothes, no privacy for the toilet, constant illumination and noise so that they had trouble sleeping, and insufficient and very poor food, such as only an apple or frozen sandwiches, which were not defrosted. Several others stated that U.S. officials asked them to sign documents in English which they couldn’t understand, did not ask them if they were afraid to return to Mexico, and did not provide information about what was happening or going to happen to them. Two parents reported being separated from their children at times in U.S. detention without explanation. One mother reported that a U.S. official kicked her children as he was walking by and said she had seen him do the same to other children.

Another father spoke about his experience with U.S. authorities. His evaluation stated that when the father was apprehended by U.S. authorities after being kidnapped by gangs in Mexico:

“[H]e had injuries from the beating and could barely walk. He begged to be seen by a doctor but was never allowed to. He and his son were put in the ‘ice chest,’ the cold holding facilities. They were sometimes separated…. He begged not to be sent back, telling the officials about his kidnapping just near Reynosa and threats of worse harm if he were returned to Mexico. He was sure that the kidnappers knew of the forced return to Mexico and would be waiting for him. He pleaded for his child to be allowed to stay in the U.S., only to keep him safe. ‘I told them I didn’t even care about myself anymore, with everything I’d been through. I said I would rather be sent back to Venezuela to be killed – at least someone would bury me. Just take my child.’ He and his son were released on the [U.S. border] bridge with nothing but their passports and permission to remain in Mexico for 180 days while their asylum case was being adjudicated. His phone and the rest of their meager possessions had been taken by the U.S. officials and never returned.”

Violations of MPP Exemption Rules

The Department of Homeland Security outlines several categories of people who are exempt from MPP, including those with known physical or mental health issues. However, the medical records of a seven-year-old child enrolled in MPP revealed that she has lissencephaly, a rare brain disorder causing severe developmental delays and seizures. The data set also includes: people with autism (two); epilepsy (one); HIV (two); diabetes and hypertension (one); heart arrythmia (one); bacterial infection (one); a six-year-old child with Down syndrome, who has a congenital heart defect causing low oxygen levels and cyanosis of the lips; and a non-binary person with known mental health issues. Psychological conditions resulting from trauma (addressed in the Clinical Findings section below) may also qualify people for exemption from MPP.

People with medical vulnerabilities face even greater danger under MPP. Of note, the six-year-old with Down syndrome was kidnapped and held at a hotel with her mother and then provided no food or water until a $5,000 ransom fee was paid to the kidnappers. Likewise, according to a clinician who evaluated a child with autism, “Though the living conditions in Matamoros are difficult for everyone, for a child with autism the conditions are akin to psychological torture with around-the-clock exposure to his triggers.”

The affidavits also demonstrate that U.S. officials are returning people to Mexico with medical needs without their medications. A 19-year-old man with epilepsy who fled gang violence in Honduras states that when he appeared at the U.S. border to request asylum, he told officers that he had epilepsy and that he was carrying medication for his condition. The officers took the medication from him and placed him in a cell before returning him to Mexico without his medication. He had a seizure as a result.

Clinical Findings

Of the 95 evaluations, clinicians made a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder in 84 people, major depressive disorder in 44, and generalized anxiety disorder in 14. Many debilitating psychological symptoms were documented by clinicians, including inability to sleep at night, frequent flashbacks, crying, irritability, hyperarousal, nightmares, and difficulty concentrating.

For 21 people, clinicians made other psychological diagnoses, including dissociative disorder, panic disorder, and somatic symptoms consistent with trauma. In 12 of the cases, clinicians documented dermatological findings, including linear scars on the torso, arms, legs, or face consistent with being cut, and thickened hyperpigmented skin consistent with being burned.

For 64 people, clinicians found two or more diagnoses. Clinicians concluded in several cases that living in an insecure environment was exacerbating the client’s psychological symptoms. In others, although the symptoms the clients reported did not meet criteria for a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder or clinical major depression, clinicians still documented trauma symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of acute stress reaction, including hypervigilance, flashbacks, intense fear, and headaches.

Conditions at the Border

People reported unsanitary and unsafe living conditions, with poor access to services. Several people mentioned food and housing insecurity due to not being able to find work. The asylum seekers’ housing situation was not mentioned in all affidavits, but, of the affidavits reporting on housing, most respondents were either living in a tent camp (23) or in a rented apartment, house, or room (22), often shared with others. Several others reported living in a shelter (six), hotel (three), with community hosts (three), or in a church (one). One man mentioned being unable to find basic necessities like diapers for his child, or even food. Although a few people reported having access to non-profit medical assistance for migrants, others reported that they did not have access to medical and mental health services. One evaluator reported:

“The client notes that it has been very difficult for her in the camp with HIV, as she gets intermittent fevers and diarrhea, and her health has been precarious. Her HIV can be well managed in a stable environment, but it has been very difficult for her in the camp. Chronic medical conditions such as HIV cannot be easily supported in an outdoor encampment.”

A number of parents (six) mentioned their concern that their children did not have access to schooling.

Policy Framework

In February 2019, immigrant advocacy organizations challenged the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), alleging violations of the U.S. Immigration and Nationality Act, the Administrative Procedure Act, and U.S. legal obligations under international law not to return people to countries where they face severe harm or death (a human rights violation known as refoulement). The union of asylum officers submitted an amicus brief[24] in support of the case, stating that MPP “violates our international and domestic legal obligations” and is “entirely unnecessary” to respond to people arriving at the border.

A federal appeals court has ruled[25] that MPP “clearly violates” U.S. immigration law by not allowing asylum seekers to remain in the United States during their proceedings and exposes people to “extreme and irreversible harm” by returning them to Mexico without rigorously assessing the danger they face prior to sending them back. Subsequently, in March 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed[26] the government to continue to implement the policy while its legality was being assessed. In October 2020, the Supreme Court granted certiorari, saying it would hear the MPP case[27] Innovation Law Lab v Wolf.[28]

The United States has ratified the 1967 UN Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees[29] and the UN Convention Against Torture,[30] committing to a legal obligation to provide international protection to people fleeing persecution and torture. This commitment includes respect for the prohibition on refoulement (a French term meaning “repulsion” or “return”), that “No Contracting State shall expel or return (refouler) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” Non-refoulement also implies an obligation to temporarily admit asylum seekers at the border in order to assess their asylum claims and to ensure meaningful review of their case, including an assessment of the harm they will face if removed to another country.

The Trump administration stated that it would make exceptions for “vulnerable” migrants on a case-by-case basis, with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) MPP Guiding Principles[31] specifying that migrants with “known physical/mental health issues” should not be sent to Mexico under the policy. Where DHS enforcement practices knowingly create serious health risks, for example by sending people to Mexico who have known physical or mental health issues, the U.S. government may not be meeting its obligation to respect, protect, and fulfill the right to life.[32] Under the U.S. Constitution, no person may be deprived of life or liberty without due process of law; this right must be respected in tandem with international rights not to be subjected to persecution or torture.

The Trump administration’s MPP policy marks the first time that the U.S. government has systematically returned people presenting at the border to another country while considering their cases for asylum in the United States. The incoming Biden administration has pledged to reverse MPP[33] within its first 100 days, stating: “Biden will end [the Trump administration’s detrimental asylum] policies, starting with Trump’s Migrant Protection Protocols, and restore our asylum laws.” People enrolled in MPP have already been processed by U.S. Customs and Border Protection; thus, admitting them into the United States only requires signing their parole form and permitting them to enter through the port.

Conclusions

Considerable evidence indicates thatit is not safe for migrants to remain in Mexico while they await the determination of their U.S. asylum status. Bona fide refugees, seeking asylum in the United States, have faced severe harm and violence in Mexico as a result of the so-called Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), which violate established international human rights and U.S. law. Resilient people fleeing harm have been forced to expose themselves to further harm. These traumatic experiences compound the trauma experienced in their home country and have had a significant negative impact on their physical and mental health. Vulnerable people, including those with significant medical conditions and small children, have also been subjected unnecessarily to inhumane conditions, including lack of food and housing insecurity, as well as lack of access to medical care and exposure to extreme weather conditions. Moreover, at least 11 people in Physicians for Human Rights’ data set belonged to categories which should have exempted them from being enrolled in MPP in the first place, and at least one third of those evaluated had a stable and safe living plan in the United States with family and friends. Ultimately, the asylum seekers in this study chose to continue waiting in Mexico because, as our data indicates, the dangers they faced in their home countries were even greater. Forcing people to make this dangerous choice is heinous, and it is also a violation of obligations under U.S. and international law.

Policy Recommendations

To the U.S. Government:

Once in office, President Biden should issue an executive order to:

- Parole people enrolled in the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) into the United States to await their immigration proceedings in community settings, such as through the family case management program. The order should clarify that people paroled in from MPP should not be sent to immigration detention;

- Ensure adequate resources are provided for surge capacity of trained personnel, such as medical and mental health professionals and child welfare experts, to ensure that immigrants have a humane reception at the border, and support to state agencies to provide social services and mental health counseling to people harmed by MPP; and

- Pledge to consider establishing a commission and a victims’ compensation fund for all those wrongfully impacted by these policies.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) should:

- Immediately admit all people enrolled in MPP into the United States, paroling them into community settings, and rescind MPP so that no one else will be sent back to Mexico under the program;

- Issue clarifying guidance that Section 235 of the Immigration and Nationality Act does not permit return to countries not covered by a safe third country agreement without full consideration of dangers the individual may face if returned;

- Follow Public Health Recommendations for Processing Families, Children and Adults Seeking Asylum or Other Protection at the Border[34] while re-opening the border; and

- Announce admissions periods at the border which would prioritize admission for the following groups of asylum seekers: 1) those waiting the longest; 2) those in imminent danger; and 3) those with significant health conditions. Announcements regarding the new procedure should be made widely available at both sides of the border, and Customs and Border Protection should ensure that people can travel safely to their next destination, including in coordination with shelter providers and with asylum offices to facilitate change of venue.

The Department of Justice should:

- Withdraw the appeal on Innovation Law Lab v Wolf and dismiss the case by agreeing to a settlement on MPP in the pending litigation; and

- Work with DHS and congressional oversight bodies to initiate an investigation to determine appropriate redress for people harmed by this policy. This includes restoring eligibility for relief for people removed under these policies and considering the negative impact on their physical and mental health, as well as the harm to their asylum case, from lack of access to legal counsel and forensic evaluations.

To the Government of Mexico:

- Ensure that people seeking asylum in the United States are able to access ports of entry, including by helping the U.S. government to widely publicize necessary new policies which reverse MPP, not deporting migrants still in Mexico to other countries, releasing any migrants seeking asylum in the United States currently held in Mexican immigration detention, and informing the United States that Mexico will no longer accept anyone returned to Mexico under MPP;

- Grant humanitarian visas and work permits to immigrants and asylum seekers and allow non-citizens to access public health facilities for emergency and preventative care, while working with civil society and UN agencies to improve access to other essential services; and

- Address human rights violations in Mexico that drive asylum seekers toward the U.S. border, including violence by state and non-state actors and impunity caused by a failure of accountability for violence.

Acknowledgments

Physicians for Human Rights thanks the legal and humanitarian partners on the U.S.-Mexico border, without which these evaluations would not be possible, including Las Americas, Lawyers for Good Government (Project Corazon), Matamoros Resource Center, and Project Lifeline. Most of all, we thank the courageous and resilient asylum seekers and their legal representatives who shared their stories.

This report was written by PHR staff Kathryn Hampton, MSt, senior asylum officer; Michele Heisler MD, MPA, PHR medical director and professor of internal medicine and of public health at the University of Michigan; Ranit Mishori MD, MHS, PHR senior medical advisor, professor of family medicine at the Georgetown University School of Medicine, director of the department’s Global Health Initiatives, and interim chief public health officer for Georgetown University; Joanna Naples-Mitchell JD, U.S. researcher; and Elsa Raker, asylum program associate; and by researchers at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine Human Rights Clinic (KHRC) medical students Rebecca Long and Madeleine Silverstein, resident Madeline Ross, MD and the faculty advisors for KHRC: Mary Cheffers MD, clinical faculty of emergency medicine and Todd Schneberk MD, MS, MA, assistant professor of clinical emergency medicine and Gehr Center for Health Systems Science and Innovation faculty.

This report has benefitted from review by PHR staff, including DeDe Dunevant, director of communications; Karen Naimer, JD, LLM, MA, director of programs; Donna McKay, MS, executive director; Michael Payne, senior advocacy officer; Susannah Sirkin, MEd, director of policy, and Raha Wala, JD, director of advocacy. Hajar Habbach, MA, former Asylum Program coordinator, Phelim Kine, former director of research and investigations, and Tamaryn Nelson, MPA, former interim and deputy director of research and investigations, helped develop the research methods, ethics review, and data collection for this report. The report also benefitted from external review by PHR Board Member Gail Saltz, MD and by PHR Advisory Council Member Gerson Smoger, JD, PhD.

The report was reviewed, edited, and prepared for publication by Claudia Rader, MS, PHR senior communications manager. Hannah Dunphy, digital communications manager, prepared the digital presentation.

Endnotes

[1] Department of Homeland Security, Migrant Protection Protocols, Jan. 24, 2019, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2019/01/24/migrant-protection-protocols.

[2] Stephanie Leutert and Savitri Arvey, “Immigrant Protection Protocols Update,” Strauss Center, University of Texas at Austin, Dec. 2020, https://www.strausscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/MPPUpdate_December2020.pdf.

[3] TRAC Immigration, Details on MPP (Remain in Mexico) Deportation Proceedings, Syracuse University, data through Nov. 2020, accessed on Jan. 13, 2020, https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/mpp/.

[4] “ACLU Comment on Appeals Court Stay Order in Remain in Mexico Challenge,” ACLU, Mar. 4, 2020, https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/aclu-comment-appeals-court-stay-order-remain-mexico-challenge.

[5] “ACLU Comment on Supreme Court Stay Ruling in Remain in Mexico Challenge,” ACLU, Mar. 11, 2020, https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/aclu-comment-supreme-court-stay-ruling-remain-mexico-challenge.

[6] “Publicly Reported MPP Attacks,” Human Rights First, Dec. 15, 2020, https://www.humanrightsfirst.org/sites/default/files/PubliclyReportedMPPAttacks12.15.2020FINAL.pdf

[7] PHR Asylum Program, Physicians for Human Rights, https://phr.org/issues/asylum-and-persecution/phr-asylum-program/.

[8] Istanbul Protocol, Manual on the Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture or Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2004, https://phr.org/issues/asylum-and-persecution/phr-asylum-program/.

[9] Leutert and Arvey, Immigrant Protection Protocols Update.

[10] TRAC Immigration, Details on MPP Deportation Proceedings.

[11] “’Like I’m Drowning’: Children and Families Sent to Harm by the US ‘Remain in Mexico’ Program,” Human Rights Watch, Jan. 6, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/01/06/im-drowning/children-and-families-sent-harm-us-remain-mexico-program.

[12] TRAC Immigration, Details on MPP Deportation Proceedings.

[13] EFE, “Homicidios en México alcanzarían nuevo récord en 2020 pese al confinamiento, prevé gobierno,” Forbes Mexico, Sept. 2, 2020, https://www.forbes.com.mx/noticias-homicidios-mexico-nuevo-record-2020-pese-confinamiento-preve-gobierno/.

[14] Caitlin Dickerson, “Inside the Refugee Camp on America’s Doorstep,” New York Times, Oct. 23, 2020, accessed Jan. 13, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/23/us/mexico-migrant-camp-asylum.html.

[15] Lucy Bassett, Kathryn Laughon, Nora Montalvo, and Jennifer Glazier, “Living in a tent camp on the US/Mexico border: The experience of women and children in Matamoros, Mexico,” Apr. 27, 2020, https://bf7531e6-1ba5-423b-885b-debb873c76a5.filesusr.com/ugd/2fed06_a6bd4c27c6c141338caae0e424287eac.pdf.

[16] Todd Schneberk, “Testimony Submitted for the Record to the House Committee on Homeland Security Hearing on: ‘Examining the Human Rights and Legal Implications of DHS’ “Remain in Mexico” Policy,’” Physicians for Human Rights, Nov. 19, 2019, https://phr.org/our-work/resources/house-committee-on-homeland-security-hearing-migrant-protection-protocols/.

[17] Jose Mares, “Voices from the COVID-19 Pandemic: ‘In Tijuana or Matamoros, it’s become a living hell,’” Physicians for Human Rights, Sept. 1, 2020, https://phr.org/our-work/resources/voices-from-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-tijuana-or-matamoros-its-become-a-living-hell/.

[18] Hannah Janeway and Tamaryn Nelson, “Voices from the Pandemic: A Looming COVID-19 Outbreak in Tijuana,” Physicians for Human Rights, May 26, 2020, https://phr.org/our-work/resources/voices-from-the-pandemic-a-looming-covid-19-outbreak-in-tijuana/.

[19] Global Response Management, “Medical Summary for Refugee Camp: Matamoros,” Human Rights First, https://www.humanrightsfirst.org/sites/default/files/GRM%20Report%20on%20Conditions%20in%20Matamoros.pdf.

[20] Content Analysis, Population Health Methods, Columbia Mailman School of Public Health, https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/population-health-methods/content-analysis.

[21] Bianca Bruno, “Judge Finds Asylum Seekers Have Right to Counsel,” Courthouse News Service, Jan. 15, 2020, https://www.courthousenews.com/judge-finds-asylum-seekers-have-right-to-counsel/.

[22] U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Assessment of the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), Oct. 28, 2019, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/assessment_of_the_migrant_protection_protocols_mpp.pdf.

[23] Hajar Habbach, Kathryn Hampton, and Ranit Mishori, “’You Will Never See Your Child Again’: The Persistent Psychological Effects of Family Separation” Physicians for Human Rights, Feb. 25, 2020, https://phr.org/our-work/resources/you-will-never-see-your-child-again-the-persistent-psychological-effects-of-family-separation/.

[24] USCIS AFGE Union Local 1924, Amicus Curiae brief for Innovation Law Lab v McAleenan, United States Court of Appeals for the Nineth Circuit, Case: 19-15716, 06/26/2019, https://www.splcenter.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019.06.26_-_039_-_brief_of_amicus_curiae_local_1924_iso_plfs-appellees_answering_brief_affirmance_of_dcs_decision_0.pdf.

[25] Stay Order, Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, No. 19-15716 D.C. No. 3:19-cv-00807-RS Northern District of California, San Francisco.

[26] Vanessa Romo, “U.S. Supreme Court Allows ‘Remain In Mexico’ Program To Continue,” NPR WNYC, Mar. 11, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/03/11/814582798/u-s-supreme-court-allows-remain-in-mexico-program-to-continue.

[27] Bill Chappell, “Supreme Court To Hear Cases Tied To Trump’s Policies On Mexico Border,” NPR WYNC, Oct. 19, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/10/19/925371839/supreme-court-to-hear-cases-tied-to-trumps-polices-on-mexico-border.

[28] Innovation Law Lab v Wolf, https://www.aclu.org/cases/innovation-law-lab-v-wolf.

[29] UN General Assembly, Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, 31 Jan. 1967, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 606, p. 267.

[30] UN General Assembly, Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 10 December 1984, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1465, p. 85.

[31] U.S. Department of Homeland Security Migrant Protection Protocols Guiding Principles, Jan. 28, 2019, https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2019-Jan/MPP%20Guiding%20Principles%201-28-19.pdf.

[32] Kathryn Hampton, “Zero Protection: How U.S. Border Enforcement Harms Migrant Safety and Health,” Physicians for Human Rights, Jan. 2019, https://phr.org/our-work/resources/zero-protection-how-u-s-border-enforcement-harms-migrant-safety-and-health/.

[33] The Biden Plan for Securing Our Values as a Nation of Immigrants, https://joebiden.com/immigration/.

[34] Columbia Mailman School of Public Health, Physicians for Human Rights, et al., “Public Health Recommendations for Processing Families, Children and Adults Seeking Asylum or Other Protection at the Border,” Dec. 2020, https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/public_health_recommendations_for_processing_families_children_and_adults_seeking_asylum_or_other_protection_at_the_border_dec2020_0.pdf.