Executive Summary

For the past decade, Yemen has been wracked by multiple armed conflicts. The parties to these conflicts have flouted the most basic international laws and norms, including by disregarding the special protections afforded by international humanitarian law to medical facilities and personnel. A particularly destructive phase for Yemen began in 2014, when the Houthi armed group (also known as Ansar Allah) took over Yemen’s capital, Sana’a, by force, and escalated in 2015 with the intervention of the Saudi-Emirati-led coalition on behalf of the internationally-recognized government of Yemen against the Houthis. Even prior to that escalation, Yemen was one of the poorest countries in the world, with the lowest human development indicators in the Middle East and North Africa.

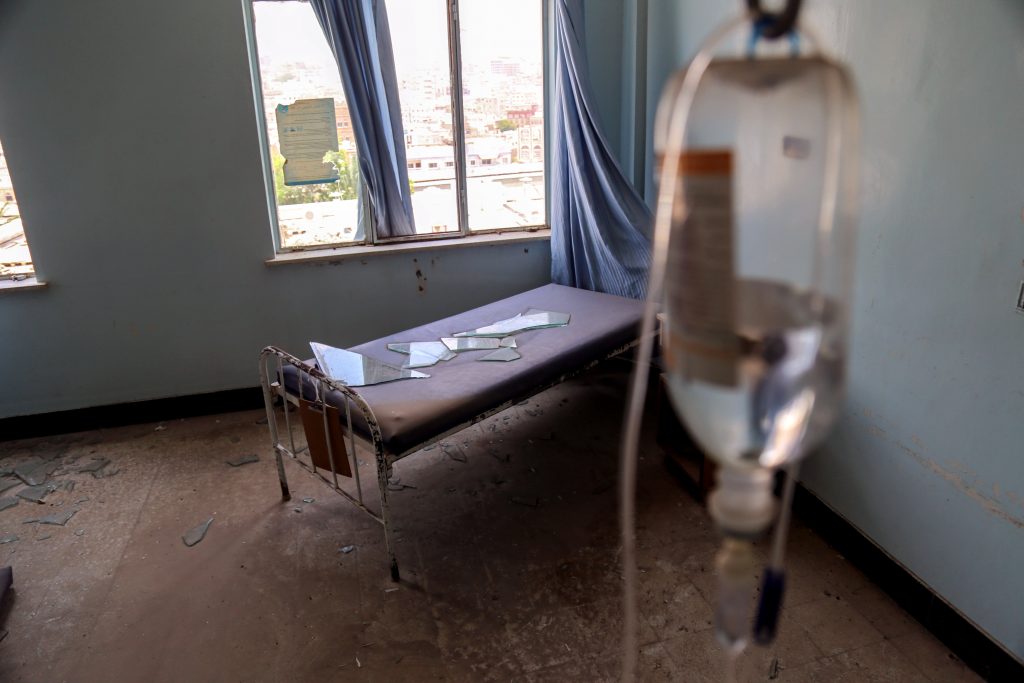

The years of conflict have turned Yemen into a humanitarian catastrophe. Its economy is crumbling. Its infrastructure is in tatters. Its health care system has almost collapsed. This state of affairs is not an arbitrary consequence of war. It is the direct result of how the conflict has been prosecuted by warring parties: with utter disregard for international law and humanitarian norms. The parties to the conflict in Yemen have waged war with a disregard for international norms that has increasingly obliterated Yemenis’ capacity to survive. Aerial attacks by the Saudi-Emirati-led coalition have taken a particularly devastating toll on the country’s critical infrastructure, including its medical units.

The warring parties in Yemen – including the Saudi-Emirati-led coalition, the Houthi armed group, and the Yemeni government – have over the course of the conflict perpetrated serious violations of international human rights law and international humanitarian law. One of the more distinctive—and devastating—abuses of the conflict has been attacks on medical infrastructure and health workers. The warring parties have damaged or destroyed health facilities through airstrikes and shelling, depriving Yemeni civilians of desperately-needed medical services. Parties to the conflict have also occupied medical facilities, commandeered the provision of medical facility services to exclude large swathes of the population, and assaulted medical professionals, among other abuses. Together, these actions violate standards firmly rooted in international humanitarian law and international human rights law to protect health facilities, health workers, and patients during conflict. They further interfere with health professionals’ ability to act in accordance with their ethical obligations.

This research report, produced by Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and Mwatana for Human Rights (Mwatana), examines attacks on medical facilities and personnel by parties to the Yemen conflict that took place between March 2015 and December 2018.

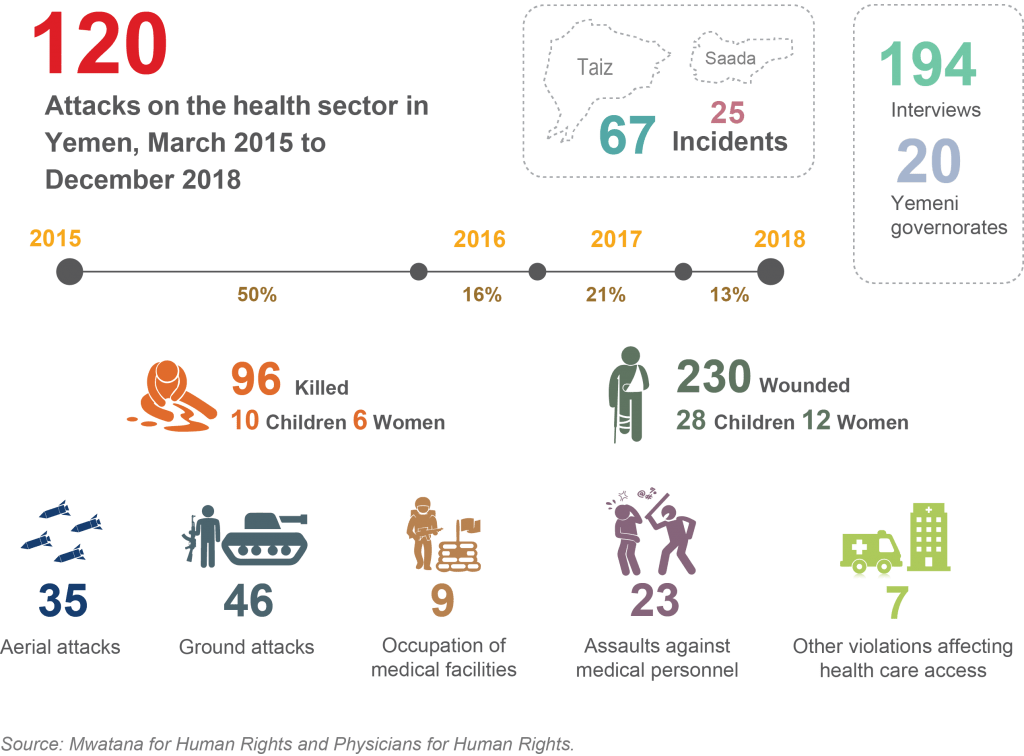

Based primarily on testimonies of witnesses and survivors, this report documents 120 attacks on health facilities and medical personnel in Yemen over a 45-month period. According to data collected by Mwatana, nearly 50 percent of all documented attacks took place in 2015, 16 percent in 2016, 21 percent in 2017, and 13 percent in 2018. The attacks killed at least 96 civilians and health workers, including 10 children and six women, and wounded 230 others, including 28 children and 12 women. Taiz was the governorate most affected by attacks on medical facilities, with 67 documented incidents. Saada governorate was also significantly affected by attacks on health care facilities, with 25 documented incidents, 22 of them airstrikes. The impact of each attack goes far beyond the civilians killed or injured. These attacks have contributed to the virtual collapse of Yemen’s health system, an outcome that has had devastating impacts on the country’s civilian population.

The documented incidents fall into four main categories of attacks: aerial attacks (35), ground attacks (46), occupation of medical facilities (10), assaults against medical personnel (24), and other violations affecting health care access (7). These categories overlap in many of the documented incidents, with aerial and ground attacks often affecting medical personnel, and occupation and militarization leading in some cases to the direct targeting of health facilities by opposing forces.

The documented incidents are not comprehensive and do not represent the total number of attacks on the health sector. Nevertheless, they illustrate patterns of attacks on health, their impact, and specific violations committed in their execution.

Saudi-Emirati-led coalition forces have primarily destroyed and damaged hospitals, clinics, vaccination centers, and other medical points through aerial attacks. The coalition’s attacks impacting health facilities assigned exclusively to medical purposes are evidence of its disregard for these structures’ protected status and apparent unwillingness or inability to comply with the principles of distinction and proportionality – including through target verification, timing of attacks, weapons choice, and prior warning. The Houthi armed group’s and other warring parties’ use of indirect fire weapons with wide-area impact– including mortars – that affected health facilities as documented in this report appears indiscriminate in nature. The Houthis’ and other armed groups’ occupation of health facilities points to a more deliberate violation of the protected status of medical structures and effectively denies medical services to populations in need. Other armed forces, including those supported by individual coalition member states, have commandeered and looted medical facilities and intimidated, and threatened health workers.

International humanitarian law provides special protection for medical personnel and facilities to ensure the functioning of health care throughout a conflict. Yet, attacks on health care, many appearing to amount to serious violations of international humanitarian law, have been routine throughout the course of the conflict in Yemen. The coalition forces’ airstrikes on civilians and civilian infrastructure and the Houthis’ use of weapons with wide-area impact in densely populated urban settings have–over and over again–violated the principles of distinction, proportionality, and precaution set out in treaty and customary international humanitarian law. In Mwatana’s and PHR’s assessment, many of these violations may amount to war crimes. Military commanders and civilian leaders may be prosecuted for war crimes when they knew or should have known about these crimes and took insufficient measures to prevent them or punish those responsible.

The warring parties in Yemen have repeatedly violated foundational principles of international humanitarian law in their attacks on health care and have perpetrated these abuses with total impunity. This report seeks to contribute to documentation and investigation efforts, so that perpetrators of war crimes and other violations can be held accountable and survivors given redress.

Key Recommendations

To the Parties to the Conflict:

- Respect the protection afforded to medical units and health services and permit health workers to fulfill their ethical responsibilities of providing impartial care to those in need.

- Facilitate safe, rapid, and unhindered access for humanitarian supplies and personnel to all affected governorates in Yemen.

To the Houthi Armed Group:

- Respect the protected status of medical facilities and withdraw armed personnel from in or around medical centers.

- Cease using medical centers for military purposes.

- Abide by the “no weapons” policies of hospitals and other health facilities.

- Investigate all incidents of restricting, denying, or confiscating humanitarian aid, and hold those responsible accountable.

To the Yemeni Government and Saudi-Emirati-led Coalition:

- Abide by the principles of distinction, proportionality and precaution in conducting military operations.

- Conduct credible, impartial, and transparent investigations into alleged violations of the laws of war and prosecute military personnel, including as a matter of command responsibility, responsible for war crimes in Yemen.

- Provide prompt and adequate redress for civilian victims and their families for deaths, injuries, and property damage resulting from wrongful attacks, and adopt a unified, comprehensive, and easily accessible mechanism for providing ex gratia (condolence) payments to civilians who suffer losses due to military operations, regardless of the attack’s lawfulness.

Background

The Development of the Conflict

For the past decade, Yemen has been wracked by multiple armed conflicts. The parties to these conflicts have flouted the most basic international laws and norms, including by disregarding the special protections afforded by international humanitarian law to medical facilities and personnel throughout a conflict.[1] The latest and most destructive phase of the conflict began in September 2014, when the Houthi armed group,[2] along with forces loyal to former president Ali Abdullah Saleh,[3] forcibly seized the capital, Sana’a, from the control of forces loyal to President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi.[4] From that point, the conflict between the Houthis and forces loyal to President Hadi steadily intensified.[5]

In March 2015, President Hadi called first on the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and the Arab League and then on the United Nations Security Council to intervene on his government’s behalf against the Houthi armed group.[6],[7] Saudi Arabia and other members of the GCC responded by forming a military coalition[8] and intervening in Yemen in support of President Hadi. The United States, the United Kingdom, and members of the European Union backed the Saudi-Emirati-led coalition, providing its members with weaponry and operational support. The United Nations Security Council responded to that intensification of the Yemen conflict with the adoption of resolution 2216 on April 14, 2015. Resolution 2216 demanded an end to violence in Yemen and imposed sanctions – including an asset freeze, arms embargo, and a travel ban – on leaders of the Houthi and Saleh armed groups.[9] Several rounds of peace talks have, as of this writing, failed to produce a sustainable ceasefire agreement.[10] The last negotiated ceasefire agreement, centered on the port city of al-Hudaydah, was reached in Sweden on December 13, 2018. It includes the ceasefire in al-Hudaydah, as well as a prisoner exchange agreement and a “statement of understanding” on the status of the city of Taiz, one of the main points of convergence of the conflict.[11] Implementation of these agreements has stalled, however, and the conflict, with its ongoing unlawful targeting of health care infrastructure and health workers, continues.[12]

The Human Toll of the Conflict

Even prior to the most recent escalation of the conflict, Yemen was one of the poorest countries in the world, with the lowest human development indicators in the Middle East and North Africa.[13] The years of intense fighting have led to tens of thousands of casualties[14] and produced a humanitarian catastrophe.[15] Conflict and instability have pushed Yemen to the brink of socioeconomic ruin.[16] These economic conditions, combined with the warring parties’ relentless destruction of infrastructure and denial of humanitarian access, have led to the virtual collapse of basic social services, including Yemen’s fragile health care system.[17] Attacks on health care infrastructure have damaged or destroyed a large number of medical facilities at a time when the need for health care is more pressing than ever.[18] Motivated by alarming patterns of systematic destruction of health facilities in Yemen and other countries, the UN Security Council in 2016 adopted Resolution 2286 condemning attacks on the medical sector and demanding an end to impunity for those responsible. Many health care facilities have shut down due to a lack of funding, medicine, and staff.[19] By the end of 2016, more than half of Yemen’s health facilities had closed,[20] and those that remained operational lacked specialists, essential equipment, and medicines.[21] There is a significant shortage of medical professionals, with only 10 health workers per 10,000 people. This ratio is far below what WHO considers a minimum of 22 health workers per 10,000 people necessary to provide the most basic health coverage.[22] Considering that 19.7 million people in Yemen lack adequate health care, the costs of the death of a health worker or the loss of another hospital are immense.[23] Outbreaks of communicable diseases, including diphtheria and cholera, are affecting a large number of Yemenis, amplified by a conflict-linked drop in vaccination and the breakdown in the country’s water and sanitation systems.[24] As of August 2018, there had been approximately 2,036,960 suspected cases of cholera, including 3,716 fatal cases of the disease.[25]

Methodology

Mwatana for Human Rights (Mwatana) and Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) co-authored this report. The findings are based on data collected by Mwatana between 2015 and 2018 and analyzed by both Mwatana and PHR. The data examined in this report was gathered as part of a wider effort by Mwatana to document human rights abuses and violations of international humanitarian law within the context of the conflict in Yemen. Twenty-four Mwatana researchers in 20 Yemeni governorates collected data through semi-structured interviews with more than 194 witnesses and survivors and direct observation of scenes of attacks. Mwatana researchers obtained verbal informed consent from every survivor and witness whose testimony was included. The information was de-identified by PHR researchers to maintain full confidentiality.

Through their extensive local networks, Mwatana’s researchers investigated reports of specific violations – including attacks on medical facilities – by parties to the conflict. Researchers visited the locations of attacks when conditions permitted and gathered multiple testimonies and photographic evidence where possible to document and verify the details of each incident. Researchers aimed to corroborate each incident with a minimum of three independent witness statements. They relied upon fewer testimonies when security conditions prevented them from collecting more information. The research team cross-checked testimonies internally and verified them against other sources of information, including news, human rights, and investigative reports for validation. It should be noted that security conditions often prevented field researchers from visiting attack sites immediately following the occurrence of attacks.

This report groups documented incidents under thematic headings to highlight the primary patterns of attacks on health that have been a defining feature of the conflict in Yemen. The report describes a limited number of attacks on health in Yemen and does not represent a comprehensive documentation of such violence. While Mwatana has documented 120 attacks on health from 2015 to 2018 (a complete list is provided in the annex), this report highlights only a portion of those incidents, selected to reflect examples of types of attacks by different perpetrators of the attacks. PHR and Mwatana scrutinized all available documentation, including witness statements, photos, and research notes to provide an in-depth analysis of individual incidents as well as to document the patterns and impact of attacks on health in the Yemen conflict. The report aims to provide a snapshot of unlawful attacks on health facilities and personnel by parties involved in the Yemen conflict.

Findings

Mwatana has documented 120 attacks on the health sector in Yemen between 2015 and 2018 affecting health facilities, medical professionals, and patients’ access to health care. According to data collected by Mwatana, nearly 50 percent of all documented attacks took place in 2015, 16 percent in 2016, 21 percent in 2017, and 13 percent in 2018. The attacks killed at least 96 civilians and health workers, including 10 children and six women, and wounded 230 others, including 28 children and 12 women. Taiz was the governorate most affected by attacks on medical facilities, with 67 documented incidents.[26] Saada governorate was also significantly affected by attacks on health care facilities, with 25 documented incidents, 22 of them airstrikes.

The documented incidents fall into four main categories of attacks: aerial attacks (35), ground attacks (46), occupation of medical facilities (9), assaults against medical personnel (23), and other violations affecting health care access (7). These categories overlap in many of the documented incidents, with aerial and ground attacks often affecting medical personnel, and occupation and militarization leading in some cases to the direct targeting of health facilities by opposing forces. The highlighted cases indicate that the parties to the conflict in Yemen have repeatedly violated foundational principles of international humanitarian law in their attacks on health care.

Airstrikes on Health Facilities

Airstrikes have been a defining feature of the Yemen conflict, devastating the country’s infrastructure and causing significant civilian casualties.[27] The Saudi-Emirati-led coalition – the party which maintains near-exclusive control over airpower in the conflict – has conducted an estimated 19,512 air raids[28] since its intervention in Yemen began in 2015.[29] The coalition has repeatedly carried out attacks that have impacted civilians and civilian objects protected under international humanitarian law. As of June 2019, coalition airstrikes remain the leading cause of conflict-related civilian deaths, with 67 percent of civilian fatalities resulting from direct strikes, despite the significant decrease in the number of airstrikes impacting civilians in Yemen since November 2018.[30]

Mwatana has documented 35 coalition aerial attacks on 32 individual health facilities between 2015 and 2018. The 35 airstrikes killed at least 31 people and medical workers and wounded 56 civilians and health workers in 10 governorates: Amanat al-Asimah, Amran, Hajjah, al-Hudaydah, al-Jawf, Lahj, Marib, Saada, Sana’a , and Taiz. Most airstrikes caused significant damage to the facilities in question, destroying vital medical units and causing widespread disruptions in access and service provision.

In six of the documented cases, Houthi forces had been occupying the facility on or near the date of attack, thereby compromising its protected status. The majority of coalition attacks took place in 2015, September being a particularly violent month, with six recorded incidents. Saada governorate, the heartland of the Houthi movement, was the most affected by coalition airstrikes, with 27 documented attacks on health facilities.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have played leading roles in the aerial campaign. The coalition they lead has relied on aircraft, munitions, and maintenance provided by the United Kingdom,[31] the United States,[32] and members of the European Union.[33] In addition, the United Kingdom[34] and the United States have provided intelligence and operational support to the coalition, including through the deployment of military advisors at coalition command level.[35] From April 2015 to November 2018, the United States provided mid-air refueling to coalition air forces.[36] Rising public outrage over the bloodshed – especially in the aftermath of the extrajudicial killing by Saudi officials of journalist Jamal Khashoggi[37] in Istanbul – has led several governments to decrease their cooperation with and support of the coalition. The Danish, Dutch,[38] Finnish[39] and German governments, have all restricted or suspended arm sales to Saudi Arabia, and Norway has suspended exports of munitions to the UAE.[40] Calls for restrictions of arms continued to grow into 2018. Despite growing internal opposition and legislative and judicial efforts to halt arms sales to members of the coalition, France,[41] Spain[42], the United Kingdom, and the United States continue to support the coalition with weapons and other military materiel.

In addition to carrying out indiscriminate and disproportionate airstrikes, the Saudi-Emirati-led coalition has been criticized for lack of transparency in its operations.[43] It remains unclear what precautions the coalition has adopted to minimize harm to Yemen’s health facilities and personnel.[44] These precautions would include clarifying the methods the coalition uses to carry out proportionality assessments or to distinguish between civilians and combatants, as well as the steps, if any, the coalition has taken to discipline or hold accountable members of its armed forces credibly implicated in international humanitarian law violations or to provide redress to civilian victims of unlawful attacks.[45] A report published in August 2018 by the UN Group of Eminent Experts on Yemen highlighted the coalition’s failure to abide by the laws of war and pointed to repeated violations of the principles of distinction and proportionality.[46] The report also criticized the use of double-tap attacks[47] and disregard for no-strike lists.[48],[49] The Group’s findings bring into question the coalition’s willingness or ability to abide by international law – or even to stick to its own procedures – and demonstrate the coalition’s disregard for the protection of civilians and civilian structures.[50] Evidence of the coalition’s continued failure to comply with international law has led the Group of Eminent Experts – the body mandated by the UN with investigating violations and abuses in Yemen – to conclude that specific coalition air strikes may have amounted to war crimes.[51]

The case below, of an attack by coalition forces on a hospital in Hajjah Governorate, highlights one example of coalition aerial attacks on medical facilities in Yemen.

August 15, 2016 – Airstrike on Abs Governmental Hospital, Abs District, Hajjah Governorate

At approximately 3:40 p.m. on Monday, August 15, 2016, coalition aircraft bombed the Medecins Sans Frontières (MSF)-supported Abs Governmental Hospital in Hajjah governorate. According to witnesses and survivors interviewed by Mwatana’s researchers in the aftermath of the attack, the strike hit the hospital’s main courtyard, severely damaging the emergency room, the maternity ward, and the pharmacy, among other sections. The facility was clearly identified by six MSF logos visible from the air,[52] and MSF had repeatedly shared its coordinates with coalition forces. The attack occurred without prior warning and killed 19 people, including five children, and injured 24 others.[53] There are no indications that the facility’s protected status was compromised in any way (such as by having sheltered able-bodied combatants or being used for other military purposes) prior to the attack, which could have caused it to lose its protected status under the Geneva Conventions.[54] In its assessment of the incident, the Joint Incident Assessment Team (JIAT)[55] – a body created by the coalition to investigate claims of civilian casualties – classified the attack as an “unintended error.” The attack forced the facility’s closure for three months. In PHR and Mwatana’s assessment, the attack against the Abs Rural Hospital was a serious violation of the laws of armed conflict and appears to constitute a war crime.

Witnesses stated that 10 to 15 minutes prior to the attack, a vehicle drove into the courtyard of the hospital, transporting at least one civilian who had been injured in a coalition airstrike on a Houthi checkpoint in the town of Beni Hassan, about 16 km northwest of Abs.[56] “He came in with shrapnel wounds to his face and body. He was an ice cream salesman, not a Houthi,” one of the hospital guards said. In its investigation report on the attack,[57] MSF stated that the car was visually inspected by an employee at the hospital gate – as is standard practice in that facility – who reported that the passengers wore civilian clothes and that he observed no weapons in the vehicle. The air strike landed directly on the vehicle shortly after the injured man was put on a gurney and taken into the emergency room. A local school teacher who was close to the hospital when it was struck described the scene:

“When we entered the hospital courtyard, we saw a large crater, about three meters wide. All around it were car parts, bits of metal, and pieces of flesh. There was a severed human head resting on the ground. There was an overturned car in flames. There was shrapnel everywhere, and fragments of people’s bodies – halves, quarters. It was a slaughter. Many people were unidentifiable, torn apart and burnt to ashes. There was a woman’s body hanging from the metal fence. Another woman was still holding her child. Both of them were dead. We collected all the pieces and put them in a large tarpaulin.”

A Saudi general informed MSF about an hour-and-a-half after the air strike that the objective of the attack was a “moving vehicle that had entered the hospital compound.”[58] In its investigation of the attack, JIAT concluded that,[59] following an airstrike on a “gathering of Houthi leaders in the north of Abs,” coalition forces tracked a vehicle that left the location heading south. According to JIAT, the vehicle was directly targeted when it stopped by a building that “displayed no signs of being a medical facility,”[60] but turned out to be the Abs Governmental Hospital. The JIAT spokesperson went on to specify that the damage to the Abs Hospital was the unintended consequence of an attack on a “legitimate military target” – i.e. the vehicle – that happened to be in the vicinity of the medical facility.[61]

The MSF report on the incident directly contradicted JIAT’s findings. MSF specified that the facility was being used exclusively for the provision of medical services and that there were measures in place that ensured “the transparent and neutral functioning of the Abs hospital as a medical facility protected under international humanitarian law.”[62] Every witness statement collected by Mwatana described a regularly functioning medical facility packed with patients and visitors.

Shelling of Health Facilities

The use of land-based explosive weapons with wide-area impact by parties to the Yemen conflict has also caused widespread death and devastation. Mwatana has documented 46 cases of ground attacks between 2015 and 2018, which killed at least 45 civilians and wounded 14 civilians and health workers in five governorates: Aden, Amanat al-Asimah, al-Hudaydah, Marib, and Taiz. Around two thirds were directed at al-Thawra hospital in Taiz.

The inherent inaccuracy and often indiscriminate nature of weapons like mortars, unguided rockets, and artillery and their large destructive radius makes harm to civilians and vital civilian infrastructure extremely likely when these weapons are deployed in populated areas,[63],[64] as has been typical in Yemen. In fact, a 2015 study on the use of explosive weapons in Yemen by the non-profit organization Action Against Armed Violence[65] and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs found that three-quarters of ground-launched incidents targeted populated areas.[66] Houthi and pro-Houthi forces have been particularly – though not exclusively – implicated in indiscriminate ground-launched attacks on civilian areas,[67] many of which have directly or indirectly affected medical facilities.

Al-Thawra Hospital in Taiz was the victim of at least 45 documented attacks, including ground-launched attacks, armed incursions, and looting. In August 2015, the facility was attacked eight times and was hit with 22 shells in two days, damaging the hospital’s buildings and equipment and putting the facility out of service. Of the 45 attacks, 26 involved mortar shells and five involved missiles that hit the hospital. The apparent indiscriminate use of mortar shells caused severe and repeated damage to the burn center, surgical unit, emergency room, morgue, internal medicine department, gynecology department, resuscitation department, and nephrology department, as well as the doctors’ residence. The case of Taiz’s al-Thawra Hospital, as well as the other case below, highlights the severity of damage that ground-launched weapons can inflict on health facilities.

August 2, 2018 – Mortar Attack on al-Thawra Hospital, al-Hudaydah

At approximately 4:45 p.m. on August 2, 2018, al-Thawra Hospital,[68] about 1.5 kilometers south of al-Hudaydah’s harbor, was hit by three mortars. The attack killed four women and one child, wounded six adults and one child, and put thousands of civilians at risk of losing essential medical services. Mwatana and PHR found no evidence indicating the status of al-Thawra Hospital had been compromised in any way that could have led to the medical facility losing its protection from attack. In its assessment of the incident, the Panel of Experts on Yemen also stated not having “received any evidence, nor seen any allegations, that the al-Thawra Hospital was being used to commit acts harmful to the enemy on 2 August 2018.”[69] The Panel of Experts has concluded that “[the attack] amounts to an indiscriminate attack and constitutes a serious violation of international humanitarian law.”[70] Mwatana and PHR have concluded that the party responsible for the attack should have been aware that the area was teeming with civilians, and that it was home to an extremely important medical facility. While the existing evidence does not lend itself to a conclusive verdict on the perpetrator of the attack, the details of the incident indicate the attack constituted a serious violation of international humanitarian law, and an apparent war crime.

The attack on al-Thawra hospital occurred while first responders were bringing dozens of civilians into the hospital who were wounded in a mortar attack on the fish market at the al-Hudaydah harbor.[71] As casualties from the harbor attack were streaming into al-Thawra Hospital about half a kilometer away, three mortars fell around the facility. A fish trader injured by a mortar explosion at the harbor, who had been taken immediately to al-Thawra Hospital by his brothers, described the scene:

“I got to the emergency room, where doctors put me on an IV. Barely 10 minutes had passed when we heard a very close explosion. We were told by people in the emergency room that the hospital’s gate was just hit. I ripped the IV out of my arm and started running. I was in one of the hospital’s halls when I heard a second explosion, and then a third. I left the hospital from the northern gate, got on a motorbike and rode home.”

The first mortar landed on busy al-Thawra street right in front the hospital’s eastern gate, killing and injuring a number of bystanders. A local shop owner told Mwatana “One of the mortars landed as a pregnant woman was getting off a bus. There were about four girls around her. They were all hit, along with others, including some of the casualties of the attack on the fish market. I watched all of this unfold and I was completely frozen. I couldn’t move.” A second mortar landed less than a minute later on the hospital’s statistics center, in the hospital compound, puncturing its roof, followed by a third that landed about 200 meters north of the hospital’s entrance in front of Ibn al-Nafis Pharmacy.

While the targeted areas are at least 500 meters apart, the attacks on the harbor and the attacks on the area surrounding al-Thawra Hospital occurred within the same area of al-Hudaydah city, around the same time of day, and were carried out using the same type of munitions. It is difficult to know whether the hospital was the target of the attack due to the extensive damage to the surrounding area. Based on analyses of open sources, both the international investigative group Bellingcat[72],[73] and the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen[74] separately determined that the attacks were most likely perpetrated using 120mm mortars that have characteristics consistent with ordnance produced by German manufacturer Rheinmetall or its South African subsidiary Rheinmetall Denel Munitions, noting that these munitions have been supplied to Saudi and Emirati forces. Bellingcat concluded that the mortars were most likely launched from an area south of al-Thawra Hospital based on an examination of the shape of one of the craters caused by the explosions.

At the time of the attack, the Houthis were in control of most of al-Hudaydah, and the area had been witnessing a significant escalation in violence since the coalition and affiliated forces launched their offensive on the port city in June. Although within Houthi-controlled territory, the fishing harbor and the hospital were not far from an active front line, with coalition forces stationed about three kilometers south, near al-Hudaydah Airport. While both the type of munition used and the direction of the attack point to coalition forces as the perpetrators, neither Bellingcat nor the Panel of Experts was able to positively attribute responsibility, primarily due to the possibility that Houthi forces could have acquired the ordnance in question through illegal means or battlefield recovery.

Occupation of Health Facilities

In addition to air and land attacks by a variety of explosive munitions, parties to the conflict in Yemen have frequently occupied medical facilities. The Houthis and pro-Saleh military forces – including the Hassam and Abu al-Abas brigades – have used occupation and militarization of hospitals to exert control over medical services in areas under their authority. Health services have been weaponized to deny care to populations in need or to impose conditions on service providers. Armed groups have commandeered medical facilities as a means to prioritize care to their members or supporters, a direct violation of the laws protecting medical facilities and personnel and an interference with health workers’ professional ethic of nondiscriminatory health care provision. Armed groups have also used their control of medical facilities as a revenue generator by imposing access fees on civilians who need medical services.

In the documented cases, the occupation of medical facilities by armed groups was often accompanied by assaults on medical workers, the eviction of health workers and patients, the looting of equipment and medicine, and the positioning of armed groups in and around a given facility. In some cases, the occupation of medical facilities also included a temporary or permanent takeover of facilities and the replacement of civilian administrations with members of an armed group. In addition to occupying health facilities, armed groups often invaded medical facilities for short-term purposes. Mwatana has documented cases of armed groups entering hospitals and forcing medical professionals to prioritize the treatment of injured combatants, searching for and executing patients suspected of belonging to rival armed groups, and temporarily deploying armed elements within these facilities for military purposes.

In addition to restricting access to already scarce services and disrupting the normal functioning of medical facilities, occupation by armed groups also compromises the protected status of those facilities and the health workers within, thereby increasing the likelihood of attack by other parties to the conflict. In at least five cases documented by Mwatana, the occupation of medical facilities by Houthi forces was followed by coalition airstrikes on those facilities.

2011-2018 – The Occupation and Destruction of al-Ghail Medical Center, al-Ghail, al-Jawf

On July 10, 2011, Houthi forces commandeered the al-Ghail Medical Center and converted it into a military health facility dedicated to the treatment of their members and supporters as they expanded their territorial control from Saada into al-Jawf governorate. The Houthis dismissed the four medical professionals who worked at the hospital prior to the Houthi occupation and brought in their own medical staff.

The Houthi occupation of the al-Ghail Medical Center deprived the local civilian population of access to medical care, which forced them to take long, expensive, and often risky journeys for basic health services. Many residents had to drive to al-Hazem, about 40 minutes away, while others had to travel about five hours to Sana’a for specialized treatment. A local resident told Mwatana researchers how ordinary illnesses and injuries became costly and potentially debilitating in the absence of immediate access to medical care. “We’re really suffering because of the Houthi occupation of the medical center here in al-Ghail,” he said. “If one of our children or women becomes ill, even if it’s a fever or some other minor indisposition, we have to go to private clinics out of town. Many people around here don’t have the means to pay for the services, much less the travel. God only knows how they live.” Another resident echoed the same sentiments, telling Mwatana how, when his own daughter came down with a case of food poisoning, he had to pay the equivalent of $40 – a sum he could barely afford, and an insurmountable fee for many in Yemen – to transport her to a hospital in al-Hazem.

The Houthis continued to occupy the medical center for the next five years, denying its services to the local population. Following the Saudi-Emirati-led intervention in Yemen in March 2015, the area witnessed a significant escalation in violence. On February 24, 2016, coalition forces attacked the Houthi-occupied medical facility in al-Ghail with three missiles, almost entirely destroying it. After the aerial attack, one local resident lamented the state of affairs in al-Ghail: “Our directorate is completely cut off from the state. We have no access to basic services: no electricity, no water, no education, and no health services except for that one center which is now destroyed.”

Eight months after the airstrike, as lines of control shifted, forces associated with the Yemeni Popular Resistance[75] took over the ruined, inactive facility, looted what they could salvage of the medical equipment and furniture, and converted the building into a military base. A local official recalled trying to re-establish the medical center after the Houthi pull-out: “We tried to get some of the leaders at the governorate level and in the military to dissociate the medical center from all things related to combat, recover some of the looted equipment and rehabilitate the building. We’re still waiting on promises they made to us.”

The occupation, bombing, and looting of al-Ghail Medical Center is a tangle of violations that exemplifies the complexities of the conflict in Yemen. The Houthi take-over of the facility and the subsequent arbitrary denial of medical access to most civilians in the area is a violation of international humanitarian law.[76] The Houthis, when they controlled the area, denied care to the sick and wounded and failed to respect the right to access health care on a nondiscriminatory basis and to abstain from arbitrarily limiting or denying such access to the wounded and sick.

Assaults on Health Workers

Both internationally recognized government authorities and de facto authorities have a responsibility under international humanitarian law to minimize harm to civilians and civilian infrastructure, including medical infrastructure, and to allow the unhindered and impartial provision of medical care. The breakdown in the rule of law in Yemen has created a security vacuum in which the protected status of medical facilities and personnel has lost meaning. Health workers in Yemen have been seriously affected by the widespread disregard for international humanitarian law and international human rights law by all parties to the conflict. Parties to the conflict, including coalition forces, forces affiliated with the Yemeni government, and Houthi forces, have threatened, denied payment, intimidated, injured, abducted, detained, and killed health workers. Health workers in Yemen have also been repeatedly exposed to the shelling, bombing, looting, and takeover of the facilities in which they work.

Mwatana has documented a variety of attacks on medical personnel in at least nine different hospitals in Abyan, Aden, Lahj, Sana’a, and Taiz. These attacks range from intimidation and threats to physical assault. Groups including the Emirati-supported Security Belt Forces, the Houthis, al-Qaeda-affiliated armed groups, and pro-government forces have all been identified as responsible for such attacks.

Mwatana has documented 17 cases of death and injury of medical personnel working in hospitals that were attacked. In addition to the risks associated with attacks on medical facilities, health workers have also faced more specific assaults that have prevented them from providing their services to people in need. For example, on April 11, 2015, five Houthi fighters forced their way into al-Waht Hospital in Lahj Governorate. They harassed the medical staff for seven hours before evicting them from the hospital. The fighters accused the medical staff of treating terrorists (ISIS) and actively prevented them from carrying out their duties in a nondiscriminatory manner and in line with medical ethics.

In several documented cases, health workers suffered numerous abuses at the hands of hospital authorities supported by specific armed groups. Between 2016 and 2017, following months of being denied payment and benefits, a group of medical professionals working at al-Thawra Hospital in Sana’a decided to start protesting for their rights. Doctors, nurses, midwives, medical technicians, and administrators were arbitrarily arrested, disappeared, fired, and otherwise threatened and intimidated by the hospital upper administration and Houthi forces – the de facto authority in the area.

The levels of lawlessness and insecurity have also placed medical professionals and support staff at the mercy of local armed groups. Incursions into health facilities have contributed to the growing sense of fear and lack of safety associated with medical facilities. On March 19, 2017, armed members affiliated with the Yemeni Popular Resistance specifically tasked by local authorities with the protection of al-Thawra Hospital in Taiz attempted to set up a protection racket, demanding the hospital’s treasurer pay them a percentage of the institution’s earnings. When the treasurer refused, members of the armed group pulled him out of his office and physically assaulted him in front of hospital staff and patients. Five days later, at the same facility, a group of unknown gunmen forced their way into the hospital and, in full view of health workers, shot dead a patient who had just undergone surgery. The incident led to the full evacuation of the hospital and a general strike by its staff in protest. Thousands of patients were deprived of critical care for five days as a result.

These incidents illustrate how medical professionals have been the victims of a range of human rights abuses and international humanitarian law violations that have profoundly affected their ability to provide care. Because of the warring parties’ abusive practices and the failure of authorities to protect

health professionals’ independence and impartiality, many have fled areas where their services are most needed. Prior to the latest phase of the conflict in 2014, foreign medical workers comprised approximately 25 percent of the health workforce.[77] By the middle of 2015, 95 percent of foreign medical professionals had left the country, depriving Yemenis of nearly a quarter of the country’s desperately-needed health service providers.[78] Since then, the situation has only deteriorated, with medical workers reporting working in constant fear and instability.[79]

December 12, 2017 – Intimidation and Threatening of Hospital Staff, al-Thawra Hospital, Taiz

A harrowing armed incursion into al-Thawra Hospital occurred on December 12, 2017. That afternoon, armed elements believed to be affiliated with al-Qaeda attacked a group of Central Security[80] soldiers, loyal to the Hadi government, guarding the Taiz University campus. Two of the injured soldiers were evacuated to al-Thawra and were pursued by four vehicles full of armed men. The armed group shot its way past the hospital guards, into the courtyard and, from there, into the emergency ward. They then opened fire inside the emergency ward, threatening to execute doctors, nurses, and other staff members if they did not reveal the whereabouts of the two injured soldiers who were brought in earlier. A man who was visiting a patient described the scene:

“I was standing outside the intensive care unit with a number of other visitors and we see this silver [Toyota] Landcruiser and three other cars pull up to the main gate. There was a lot of screaming. I think the hospital guards were trying to prevent the men from entering the hospital’s grounds with their weapons. Moments later, we start hearing heavy gunfire and see the hospital guards running into the courtyard. The bullets got closer to us and we ran to the very end of the courtyard and hid by the burn unit. The armed men entered the main building and we kept hearing gunfire from the emergency room area for the next 30 minutes. I have no idea what happened in there.”

In the firefight that took place in the emergency ward and various hospital halls, the hospital guards managed to repel the armed men while the injured soldiers were moved to the intensive care unit on the first floor. Security reinforcements eventually reached the hospital and the armed group retreated. The attack resulted in the temporary closure of the majority of the hospital’s departments. According to a high-ranking hospital official, the psychological toll of the attack on the hospital’s staff and its patients was enormous. The official referred to the attack as a “full-fledged terrorist act,” adding that it was a “violation of all humanitarian values, religious norms, and international laws, and a heinous war crime.”

Other Violations Affecting Health Care Access and Services

Looting and restrictions on humanitarian aid have also greatly affected the medical system’s capacity to respond to Yemenis’ surging health needs.

On one side, the Saudi-Emirati-led coalition has severely limited imports of medicine, fuel, humanitarian aid, and food by imposing far-reaching restrictions on humanitarian and commercial shipping and a wide range of bureaucratic impediments[81] that have had a devastating effect on the civilian population across Yemen, especially in areas under Houthi control. Between November and December 2017, the coalition imposed a total blockade and, in the first days, prevented all humanitarian aid and commercial trade from entering the country. It then maintained extreme restrictions, including preventing much aid and nearly all commercial imports to some of the country’s most important ports, as well as humanitarian flights to Sana’a , for a period of weeks. The Group of Eminent Experts on Yemen concluded that naval and air restrictions imposed by the coalition and Yemeni government were in violation of international human rights law and international humanitarian law, including restrictions at sea and the closure of Sana’a Airport. The Group noted that “such acts, together with the requisite intent, may amount to international crimes. As these restrictions are planned and implemented as the result of State policies, individual criminal responsibility would lie at all responsible levels, including the highest levels, of government of the member States of the coalition and Yemen.”[82]

Houthi forces have also imposed local sieges,[83] routinely diverted aid, and confiscated medical and humanitarian supplies. The gravity of the situation is apparent in the recent World Food Program decision to cut general food distribution to some areas in Houthi-controlled territory.[84] This decision came after revelations of systemic abuses of aid by Houthi authorities[85] and their refusal to implement a biometrics system intended to prevent aid fraud. WFP resumed its distribution of food in Sana’a following a two-month stoppage after reaching an agreement with Houthi authorities on safeguards to ensure assistance goes to those most in need.[86]

In addition, parties to the conflict have turned visas and permissions for internal travel into mechanisms to control humanitarian assistance.[87] Delaying or denying the issuance of visas to humanitarian workers has become standard practice. In 2016, it took MSF five months of “intense negotiations” to get approval for the delivery of two trucks full of essential medical supplies into Taiz, leaving the civilian population there to deal with extreme shortages of supplies in the meantime.[88]

According to a Watch List[89] report, the UN verified 65 incidents of denial of humanitarian access by parties to the conflict between July and September 2017 in Taiz and Saada governorates.[90] Mwatana has also recorded incidents of looting of medical supplies in Taiz and al-Jawf. On July 21, 2016 armed groups affiliated with Yemeni Popular Resistance forces raided the psychiatric hospital in Taiz and looted its pharmacy. In another incident on July 5, 2017, Houthi soldiers ordered a mobile clinic to stop operating in Saada governorate, thereby suspending access to medical care to vulnerable civilians for three months.

Attacks on Health and International Law

Conflict Classification and Applicable Law

The conflict in Yemen is a non-international armed conflict in which international law obligations arise under both treaty and customary law. The fundamental principles of both treaty and customary law are that any and all parties to a conflict have an obligation to minimize harm to civilians and civilian infrastructure. Medical units have special protection. Yemen ratified the four Geneva Conventions in 1970.[91] It also ratified the two additional protocols to the Geneva Conventions in 1990.[92] In 1987, Yemen ratified the Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity.[93] Applicable law in the context of Yemen includes Common Article 3 to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, Additional Protocol (II) to the Geneva Conventions of 1977, and customary international law.

International humanitarian law is binding on both states and non-state armed groups engaged in the conflict in Yemen. All parties to the conflict, including the government of Yemen, Saudi-Emirati-led coalition forces, Houthi forces, and other non-state actors must abide by the fundamental principles of distinction, proportionality, and precaution in the conduct of hostilities.

Protections Related to Health Care under International Humanitarian Law and Customary International Law

International humanitarian law (IHL) and customary IHL provide special protections to certain civilian objects, including hospitals, clinics, medical centers, and similar facilities.[94] Hospitals may lose their protection from attack only if they are being used, outside their humanitarian function, to commit “acts harmful to the enemy.”[95] Even if a hospital is being used by an opposing force to commit acts harmful to the enemy – for example, to store weapons, shelter combatants capable of fighting, or to launch attacks – the attacking force must issue a warning to the opposing party to cease the misuse of the medical facility, set a reasonable period of time for the misuse to end, and attack only if and after the warning has gone unheeded.

International humanitarian law and customary IHL also requires that medical personnel, like doctors and nurses, and those in charge of searching for, collecting, transporting, and treating the wounded, are permitted to deliver their services impartially and are protected.[96] Punishing a person for performing medical duties in line with medical ethics or compelling a person to engage in medical activities contrary to medical ethics, is prohibited. Medical transportation, like ambulances, must also be permitted to function and be protected. Like facilities, medical personnel and transport lose their protection only if they commit acts “harmful to the enemy,” outside their humanitarian functions.[97]

International humanitarian law compels parties to a conflict to respect and protect humanitarian relief personnel, including from harassment, intimidation, and arbitrary detention. Parties to the conflict must allow and facilitate the rapid passage of humanitarian aid and not arbitrarily interfere with it. They must also ensure that humanitarian workers enjoy freedom of movement, which may only be restricted temporarily in cases of military necessity.

Yemen – like most members of the coalition, with the exception of Jordan and Senegal – is not a party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Nevertheless, many of the provisions of the Rome Statute are reflected in customary international law. Intentionally directing attacks against buildings, materials, medical units and transport, and personnel using the distinctive emblems of the Geneva Conventions in conformity with international law is a war crime, as is intentionally directing attacks against hospitals and places where the sick and wounded are collected, provided they are not military objectives. Deliberately using the presence of civilians to protect military forces from attack is also considered a war crime.

Protections of Health Care under International Human Rights Law

Yemen is a signatory to core international human rights treaties,[98] including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention against Torture, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, all of which provide specific protections to medical workers and to access to health services. These treaties remain in effect in periods of armed conflict. The government of Yemen remains responsible under the treaties in areas that fall within and outside of its effective control. De facto authorities controlling large portions of Yemen’s territory and population and exercising government-like functions, like the Houthi armed group, also have obligations to respect international human rights law.[99]

Conclusion

The findings of our investigations indicate that, over the past four years, the parties to the conflict in Yemen have committed and continue to commit serious violations of international humanitarian law and to disregard the norms that protect the sick and wounded by attacking medical facilities and medical personnel. Parties to the conflict have damaged or destroyed health facilities through airstrikes and shelling, occupied medical facilities, commandeered facilities and excluded civilians from accessing their services, and assaulted medical professionals, among other abuses. Together, these actions violate both national and international laws as well as basic norms of medical ethics and care for the sick and wounded.

These findings provide compelling evidence of abuses in Yemen. The disregard for the protected status of medical facilities and personnel has been systemic and consistent with the warring parties’ demonstrated contempt for their international legal obligations. Since 2015, the parties to the conflict have deployed strategies of war that flout international protections for health care facilities and health workers in ways that have resulted in the denial of essential health care for Yemeni civilians. These violations have been a determining factor in the virtual collapse of Yemen’s health system. Mwatana and Physicians for Human Rights call upon all warring parties in the Yemeni conflict to respect the rights and dignity of civilians in Yemen and the health workers on whom the country’s beleaguered civilian population desperately relies.

Recommendations

To Parties to the Conflict:

- Immediately cease unlawful attacks on medical facilities and personnel and end occupation of medical facilities.

- Facilitate safe, rapid, and unhindered access for humanitarian supplies and personnel to all affected governorates in Yemen.

- Abide by the core international humanitarian law principles of distinction, proportionality, and precaution.

- Comply with international humanitarian law and international human rights law, including respecting the protection afforded to medical units and health services and permitting health workers to fulfill their ethical responsibilities of providing impartial care to those in need.

- Ensure the full implementation of UN Security Council resolution 2286, including by adopting additional practical measures to enhance the protection of, and access to, health care, such as incorporating the protection of medical facilities and personnel into all military training and expanded, real-time access to a comprehensive “no-strike-list” for all active combatants.

- Conduct prompt, full, impartial, and effective investigations into attacks and other forms of interference with health care to ensure accountability for perpetrators and offer redress to victims.

- Cooperate fully with UN investigations of attacks against medical facilities and personnel, including providing unfettered access to the UN Group of Eminent Experts on Yemen.

- Where possible, ensure the prompt payment of civil servant salaries, including medical workers.

To the Houthi Armed Group:

- Respect the protected status of medical facilities and withdraw armed personnel from in or around medical centers.

- Cease using medical centers for military purposes.

- Abide by the “no weapons” policies of hospitals and other health facilities.

- Investigate all incidents of restricting, denying, or confiscating humanitarian aid, and hold those responsible accountable.

To the Yemeni Government and the Saudi-Emirati-led Coalition:

- Conduct credible, impartial, and transparent investigations into alleged violations of the laws of war and appropriately prosecute military personnel – including as a matter of command responsibility – responsible for war crimes in Yemen.

- Provide prompt and adequate redress for civilian victims and their families for deaths, injuries, and property damage resulting from wrongful attacks, and adopt a unified, comprehensive and easily accessible mechanism for providing ex gratia (condolence) payments to civilians who suffer losses due to military operations, regardless of the attack’s lawfulness.

- Establish a specialized oversight body to monitor compliance by coalition forces with operational rules in place for the protection of medical care and other protected structures.

To Canada, France, the United Kingdom, the United States and Other States Supplying Weapons to the Saudi-Emirati-led Coalition:

- Immediately cease the sale or transfer of weapons to members of the Saudi-Emirati-led coalition contingent upon full respect for international humanitarian and human rights law in coalition operations in Yemen, and comprehensive efforts toward effective accountability for all alleged crimes and violations committed throughout the conflict.

To Iran:

- Immediately cease the sale or transfer of weapons to the Houthi armed group.

To UN Member States:

- Support efforts to cease hostilities, reach a sustainable and inclusive peace, and ensure accountability for serious violations and crimes.

- Maintain financial, political, and diplomatic support for efforts to document violations of international human rights and international humanitarian law and principles, with insistence on justice and accountability for possible war crimes, and civilian redress.

To the UN Human Rights Council:

- alleged serious violations and abuses and related crimes, with an aim toward ensuring full accountability for perpetrators and justice for victims.

To the UN Security Council:

- Formally adopt the Secretary-General’s 2016 recommendations toward implementation of resolution 2286 and urge member states to abide by the recommendations.

- Use tools at the Council’s disposal, including the imposition of sanctions on persons or entities responsible for attacks on health, where appropriate under existing authorities, to push for the full and unimpeded delivery of humanitarian aid, and to support a political process as the only meaningful way of bringing an end to the conflict.

- Emphasize the human rights dimensions of the conflict in Yemen and ensure that there will be no impunity for the most serious crimes.

- Direct the Secretary-General to publish a complete and accurate list of perpetrators in the annual report on children and armed conflict, holding all of them to the same standard.

Annex: Summary of Documented Attacks on Health Facilities

Endnotes

[1] M. Goniewicz and K. Goniewicz, “Protection of medical personnel in armed conflicts-case study: Afghanistan,” European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery 39, no. 2 (2013), 107-112, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3611028/.

[2] The Houthi movement, also known as Ansar Allah, is a predominantly Zaydi Shiite revivalist political armed movement formed in the northern governorate of Saadah in 2004 under the leadership of the Houthi family. The Houthis fought six wars against the Yemeni government between 2004 and 2010. The Houthi armed group has been one of the primary parties to the going conflict that escalated in 2014.

[3] A former military officer, Ali Abdullah Saleh became president of Yemen in 1978 and ruled Yemen for the next 34 years. He left the office of the presidency in February 2012 but continued to play a significant role in Yemeni politics and the conflict itself. He died in December 2017; Brian Whitaker, “Ali Abdullah Saleh obituary,” The Guardian, December 4, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/dec/04/ali-abdullah-saleh-obituary.

[4] Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi was deputy to President Ali Abdallah Saleh for nearly two decades; he came to power through a one-candidate election; “How Yemen’s capital Sanna was seized by Houthi rebels,” BBC World News, September 27, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-29380668.

[5] On January 19 2015, the Houthis attacked president Hadi’s residence (Halim Almasmari and Martin Chulov, “Houthi rebels seize Yemen president’s palace and shell home,” the Guardian, January 20, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/20/houthi-rebels-seize-yemen-presidential-palace) and eventually placed him under house arrest. (“How Yemen’s capital Sanaa was seized by Houthi rebels,” BBC World News, September 27, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-29380668). Over the course of the next year, the Houthis expanded their control into the key port city of al-Hudaydah in western Yemen, and Taiz in the southwest(Mohammed Mukkashef, “Houthis seize strategic Yemeni city, escalating power struggle,” Reuters, March 22, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security/houthis-seize-strategic-yemeni-city-escalating-power-struggle-idUSKBN0MI08B20150322). In February 2015, President Hadi escaped his Houthi captors in Sana’a and fled to the southern port city of Aden. (Mohammed Ghobari, Mohammed Mukhashaf, “Yemen’s Hadi flees to Aden and says he is still president,” Reuters, February 21, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security/yemens-hadi-flees-to-aden-and-says-he-is-still-president-idUSKBN0LP08F20150221.) The Houthis moved to take over Aden soon after (Mukhashaf, Ghobari, “Over 120 die in Yemen as Houthis take key Aden district,” Reuters, May 6, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security/over-120-die-in-yemen-as-houthis-take-key-aden-district-idUSKBN0NR0QH20150506).

[6] United Nations Security Council, Identical letters dated 26 March 2015 from the Permanent Representative of Qatar to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council, March 27, 2015, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2015_217.pdf.

[7] “Yemen’s President Hadi asks UN to back intervention,” BBC World News, March 25, 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-32045984.

[8] The coalition initially included Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Qatar, Senegal, and Sudan. Its makeup would shift through the conflict. (“Saudi Arabia launches air strikes in Yemen,” BBC World News, March 26, 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-32061632.) Qatar eventually left the coalition in 2017, as the Gulf Crisis unfolded.

[9] “Security Council Demands End to Yemen Violence, Adopting Resolution 2216 (2015), with Russian Federation Abstaining,” United Nations, April 14, 2015, https://www.un.org/press/en/2015/sc11859.doc.htm.

[10] Alkhatab Alrawhani, “Yemen’s peace process is almost dead. Here’s how to revive it,” the Washington Post, June 12, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/06/12/yemens-peace-process-is-almost-dead-heres-how-revive-it/.

[11] “Briefing of the UN Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen to the Open Session of the UN Security Council, Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, June 17, 2019, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/briefing-un-special-envoy-secretary-general-yemen-open-session-un-security-council.

[12] Rick Gladstone, “Saudi Airstrike Said to Hit Yemeni Hospital as War Enters Year 5,” The New York Times, March 26, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/26/world/middleeast/yemen-saudi-hospital-airstrike.html.

[13] See note 3.

[14] By November 2018, the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) reported that the Yemen conflict had resulted in 17,640 civilian casualties, including 6,872 dead and 10,768 injured. The UN recognizes these numbers likely undercount the true civilian death toll. Another estimate by an independent monitoring group puts the number of civilian deaths closer to 12,000 and the number of overall reported deaths at 90,000 by June 2019. “Bachelet urges States with the power and influence to end starvation, killing of civilians in Yemen,” OHCHR, November 10, 2018, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23855&LangID=E; UN General Assembly, “Situation of human rights in Yemen,” Section V, Paragraph 23; “Yemen Snapshots: 2015-2019,” ACLED Data, 2019, https://www.acleddata.com/2019/06/18/yemen-snapshots-2015-2019/.

[15] The UN has declared Yemen to be the world’s worst humanitarian disaster, with an estimated 80 percent of the population – 24 million people – requiring some form of humanitarian or protection assistance, including 14.3 million in acute need. The needs are daunting in every sector, including health, food security, and protection, and humanitarian organizations are struggling to meet them. The expansion of the conflict has resulted in the displacement of 3.3 million people. Malnutrition affects millions, with an estimated 7.4 million people requiring services to treat or prevent malnutrition, including 3.2 million people who require treatment for acute malnutrition. “Yemen Snapshots: 2015-2019,” ACLED Data.

[16] A dramatic deterioration in economic conditions has occurred as defined by a collapse in purchasing power, a significant reduction in jobs, a cutout of salaries for civil servants, and an increase in the prices of goods, fuel, and services in the north and the south of the country; World Bank Group, “Yemen Economic Monitoring Brief,” Winter 2019, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/135266-YemEconDevBrief-Winter-2019-English-12-Mar-19.pdf.

[17] “Health system in Yemen close to collapse,” World Health Organization, 2015, http://origin.who.int/bulletin/volumes/93/10/15-021015/en/; “IRC report: Failed public health system ‘quiet killer’ in Yemen,” International Rescue Committee (IRC), March 26, 2018, https://www.rescue.org/press-release/irc-report-failed-public-health-system-quiet-killer-yemen; “Health crisis in Yemen,” International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), https://www.icrc.org/en/where-we-work/middle-east/yemen/health-crisis-yemen.

[18] Safeguarding Health in Conflict, “Impunity Remains: Attacks on Health Care in 23 Countries in Conflict, 2018,” https://www.safeguardinghealth.org/sites/shcc/files/SHCC2019final.pdf; Yemeni Archive, “Attacks against Hospitals,” Observation Database, https://yemeniarchive.org/en/database?collection=Attacks%20against%20hospitals.

[19] World Health Organization, “WHO Annual Report 2017: Yemen,” https://www.who.int/emergencies/crises/yem/yemen-annual-report-2017.pdf?ua=1, pg. 23.

[20] World Health Organization, “Survey reveals extent of damage to Yemen’s health system,” http://www.emro.who.int/media/news/survey-reveals-extent-of-damage-to-yemens-health-system.html.

[21] Health Cluster Bulletin, February 2019.

[22] “Global key messages,” Global Health Workforce Alliance, 2014,https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/media/key_messages_2014.pdf.

[23] Reliefweb, “Yemen: 2019 Humanitarian Needs Overview,” UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), UN Country Team in Yemen, Published on Feb 14, 2019, visited on Feb 28, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-2019-humanitarian-needs-overview.

[24] Fekri Dureab, Maysoon Al-Sakkaf, Osan Ismail, Naasegnible Kuunibe, Johannes Krisam, Olaf Muller, and Albrecht Jahn, “Diphtheria outbreak in Yemen: the impact of conflict on a fragile health system,” Biomed Central (Vol 19, 2019), https://conflictandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13031-019-0204-2.

[25] World Health Organization, “Cholera Situation in Yemen,”August 2019, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/EMROPub_2019_cholera_August_yemen_EN.pdf.

[26] Taiz has been one of the main points of convergence in the Yemen conflict and the site of the some of the brutal front line fighting since 2015. The city endured a violent siege by the Houthi-Saleh alliance between 2015 and 2017, and remains one of the most contested areas of Yemen. “Crisis Group Yemen Update #8,” International Crisis Group, April 5, 2019, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/yemen/crisis-group-yemen-update-8.

[27] “Yemen Snapshots: 2015-2019,” ACLED Data.

[28] “Yemen Data Project,” ACLED, https://yemendataproject.org/data.html.

[29] See note 2.

[30] “Yemen Snapshots: 2015-2019,” ACLED Data.

[31] United Kingdom Parliament, “Yemen: Giving Peace a Chance, 2019,” https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201719/ldselect/ldintrel/290/29003.htm; under “UK military support to the Saudi-led coalition.”

[32] Congressional Research Service, “Yemen: Civil War and Regional Intervention,”September 17, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/R43960.pdf, p. 3.

[33] “US and European Arms Used to Attack Yemeni Civilians,” Mwatana for Human Rights, March 6, 2019, http://mwatana.org/en/us-and-european-arms-used-to-attack-yemenis/.

[34] Arron Merat, “’The Saudis couldn’t do it without us’: the UK’s true role in Yemen’s deadly war,” The Guardian, June 18, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/18/the-saudis-couldnt-do-it-without-us-the-uks-true-role-in-yemens-deadly-war.

[35] “Yemen Data Project,” ACLED.

[36] Congressional Research Service, “Yemen: Civil War and Regional Intervention,” September 17, 2019, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R43960.

[37] “Khashoggi killing: UN human rights expert says Saudi Arabia is responsible for ‘premeditated execution,’” OHCHR, June 19, 2019, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24713&LangID=E.

[38] Jon Stone, “Germany, Denmark, Netherlands and Finland stop weapons sales to Saudi Arabia in response to Yemen famine,” The Independent, November 23, 2018, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/saudi-arabia-arms-embargo-weapons-europe-germany-denmark-uk-yemen-war-famine-a8648611.html.

[39] Dominic Dudley, “Why More and More Countries are Blocking Arms Sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE,” Forbes, September 7, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/dominicdudley/2018/09/07/why-more-and-more-countries-are-blocking-arms-sales-to-saudi-arabia-and-the-uae/#6609f6fc580a.

[40] “Norway suspends arms sales to UAE over Yemen war,” Reuters, January 3, 2018, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-yemen-security-norway-emirates/norway-suspends-arms-sales-to-uae-over-yemen-war-idUKKBN1ES1EN?feedType=RSS&feedName=worldNews.

[41] John Irish, “French weapons sales to Saudi jumped 50 percent last year,” Reuters, June 4, 2019, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-france-defence-arms/french-weapons-sales-to-saudi-jumped-50-percent-last-year-idUKKCN1T51C3.

[42] Samuel Perlo-Freeman, “Who is arming the Yemen war? An update,” World Peace Foundation, March 19, 2019, https://sites.tufts.edu/reinventingpeace/2019/03/19/who-is-arming-the-yemen-war-an-update/.

[43] Human Rights Watch, “Hiding Behind the Coalition.”

[44] The Joint Incident Assessment Team (JIAT) has only investigated a fraction of attacks that raised laws-of-war concerns and has provided very little detail on coalition forces rules of engagement and targeting practices when it comes to incidents it did investigate; Human Rights Watch, ibid.

[45] “Situation Of Human Rights In Yemen, Including Violations And Abuses Since September 2014 (A/HRC/39/43) (Advance Edited Version) [EN\AR] – Yemen,” 2018, Reliefweb, https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/situation-human-rights-yemen-including-violations-and-abuses-september-2014-ahrc3943.

[46] HRC, “Situation of human rights in Yemen.”

[47] A double tap attack is a military tactic which entails launching two strikes against the same target in close succession, with the second strike aiming to injure or kill those responding to the initial strike.

[48] No-strike lists are lists of objects or entities characterized as “protected” from targeting by military actors during the course of an armed conflict. These lists usually include verified civilian structures – e.g. health facilities, schools, water reservoirs, aid distribution points, and places of worship.

[49] HRC, “Situation of human rights in Yemen,” paragraphs 35 and 37.

[50] “Some Saudi-Led Coalition Air Strikes In Yemen May Amount To War Crimes: U.N,” Reuters, August 28, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-un-rights-idUSKCN1LD0KZ.

[51] Nick Cumming-Bruce, “War Crimes Report on Yemen Accuses Saudi Arabia and U.A.E,” the New York Times, August 28, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/28/world/middleeast/un-yemen-war-crimes.html.

[52] Robin Stein, Caroline Kim, Malachy Browne, and Whitney Hurst, “Why U.S. Weapons Sold to the Saudis Are Hitting Hospitals in Yemen,” the New York Times, May 23, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/video/world/middleeast/100000006466384/yemen-war-saudi-arabia-usa.html?rref=collection%2Ftimestopic%2FYemen&action=click&contentCollection=world®ion=stream&module=stream_unit&version=latest&contentPlacement=1&pgtype=collection.

[53] “Yemen: Death Toll Rises To 19 In Airstrike On MSF-Supported Abs Hospital In Hajjah,” 2016, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International, https://www.msf.org/yemen-death-toll-rises-19-airstrike-msf-supported-abs-hospital-hajjah. According to hospital staff members interviewed by Mwatana, those injured included two nurses, one physician, a technician, and a hospital guard.

[54] Geneva Convention IV article 19 [1949] states that medical facilities forfeit their protected status if they are “used to commit, outside their humanitarian duties, acts harmful to the enemy.” International Committee of the Red Cross, “Practice Relating to Rule 28. Medical Units,” International Humanitarian Law Database, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docs/v2_rul_rule28.

[55] “The Joint Incident Assessment Team (JIAT), a body established and run by the Saudi/UAE-led coalition in 2016 in response to claims of potential IHL violations, has been roundly condemned as ineffectual by Human Rights Watch and the United Nations Group of Eminent Experts,” “Yemen Project Release: Attacks Causing Grave Civilian Harm,” Bellingcat, September 2, 2019, https://www.bellingcat.com/news/mena/2019/09/02/attacks-causing-grave-civilian-harm/.) The JIAT is a team originally composed of 14 individuals seconded from coalition members. The team is mandated with investigating the facts, collecting evidence and producing reports and recommendations on claims and accidents during coalition operations in Yemen; Human Rights Watch, “Hiding Behind the Coalition.”

[56] In its investigation report, MSF stated that three airstrikes were reported in the area between the villages of Al-Raboa and Al-Bidah, where the village of Beni Hassan is located; Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International, “MSF internal investigation of the 15 August attack on Abs hospital Yemen: summary of findings,”September 27, 2016, https://www.msf.org/sites/msf.org/files/yemen_abs_investigation.pdf.

[57] Ibid.

[59] Nayef Al-Rasheed, “The Yemen Incident Assessment Team refutes 4 allegations made to the Arab Coalition Forces,” Asharq Al-Awsat, December 8, 2016, https://bit.ly/2N2x38z.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Ibid.

[62] MSF, “MSF internal investigation,” p. 11. According to the MSF report, there were 23 people in the surgical unit, 25 in the maternity ward, and 13 newborns and 12 children in pediatrics.

[63] Maya Brehm, “Unacceptable Risk: Use of Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas through the Lens of Three Cases before the ICTY,” PAX, November 2014, https://www.paxforpeace.nl/media/files/pax-rapport-unacceptable-risk.pdf.

[64] “Indirect Fire: A technical analysis of the employment accuracy and effects of indirect-fire artillery weapons,” ICRC,February 7, 2017, https://www.icrc.org/en/document/indirect-fire-technical-analysis-employment-accuracy-and-effects-indirect-fire-artillery.

[65] Action on Armed Violence seeks to reduce the impact of armed violence through monitoring and research of the causes and consequences of weapon-based violence. “What do we do to address the impact of weapons?,” Action on Armed Violence, https://aoav.org.uk/acting-on-weapons/key-work/.

[66] Robert Perkins, “State of Crisis: Explosive Weapons in Yemen,” Action on Armed Violence and UNOCHA, https://aoav.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/State-of-Crisis.pdf.

[67] “Yemen: Houthi Artillery Kills Dozens in Aden,” Human Rights Watch, July 29, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/07/29/yemen-houthi-artillery-kills-dozens-aden#.