This research brief was prepared from information complied by Insecurity Insight, Physicians for Human Rights, and the Center for Public Health and Human Rights, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health based on open source data. This is an update to the original data published on April 2021 that can be accessed here, and the previous brief published in October 2021, accessible here.

On February 1, 2021, the Myanmar armed forces (known as the Tatmadaw) seized control of the country, following a general election that the National League for Democracy party won by a landslide. Over the past 10 months, between February and November 2021, hundreds of people, including children, have been killed and many injured during nationwide Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) protests and violent crackdowns on those opposing the coup.

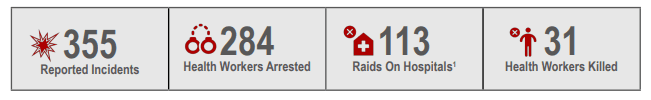

Doctors and nurses have been served with warrants and arrests for providing medical care to protesters, health workers have been injured while providing care to protesters, ambulances have been destroyed, and health facilities have been raided. At least 31 health workers have been killed.

From June to September, arrests of health workers slowed and fewer hospitals were occupied as the country grappled with the third wave of COVID-19. Overall attacks on health care since February, particularly the diversion of medical supplies to military personnel, had weakened the health system to the point where it was not able to adequately provide care to civilians seeking medical attention. Health measures put in place during the third COVID-19 wave signaled that the coup leaders intended to permit access to health care only for their supporters, disrupting access to all others. Coup leaders put restrictions on the sale and importation of oxygen cylinders and arrested health care workers providing COVID-19 treatment outside of government-run facilities. During this period, COVID-19 deaths in Myanmar were among the highest in the world.

The National Unity Government and its military wing, the People’s Defense Forces (PDF), declared war against the State Administrative Council (SAC) on September 7, 2021. Following this declaration, data collected in this report shows an increase in violence against health care compared to preceding months. Hospitals and health workers have been caught in the crossfire and are increasingly the victims of indiscriminate attacks. The data indicates that the overwhelming majority of these attacks are committed by the Tatmadaw, demonstrating consistent disregard for the protection of health care in conflict and a breach of human rights and humanitarian law. Since the beginning of the coup, government forces, including the military (Tatmadaw), police forces, and government-aligned militias, have committed over 90 percent of documented attacks against health care.

In recent months, the Tatmadaw appear to be adapting tactics initially used against members of the Rohingya minority in 2016-2017 for use against communities perceived to be sympathetic to pro-democracy forces. This includes the widespread burning and destruction of civilian homes and infrastructure, including hospitals and clinics, and the indiscriminate shelling of civilian populations.

This report highlights concerns over:

- Indiscriminate artillery and arson attacks on hospitals and clinics by Myanmar government forces.

- Attacks on medical personnel associated with the People’s Defense Force (PDF) and opposition groups by government forces.

- Continuing raids and occupation of hospitals and clinics.

- Arrests of large numbers of health workers.

- Re-arrests of recently freed health workers.

- Multiple cases of prisoner deaths in detention due to medical neglect.

- Escalating attacks on local NGOs, specifically those providing aid to displaced populations in ethnic minority areas.

This report is a collaboration between Insecurity Insight, Physicians for Human Rights, and the Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health and Human Rights as part of the Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition (SHCC). It highlights reported incidents of violence against health workers, facilities, and transport in Myanmar between February 1 and November 30, 2021, to highlight the impact on the health system as a whole. It does not include information on violence against patients. It is drawn from credible information that is available in local, national, and international news outlets, online databases, and social media reports.

Notable Developments Since Last Report

Hospitals and Clinics

Hospitals and clinics are increasingly experiencing indiscriminate artillery and arson attacks

Artillery and arson attacks are wielded against communities perceived to be sympathetic to pro- democracy forces. Since the last report in October 2021, at least four facilities were destroyed and three additional facilities damaged in fighting and indiscriminate attacks against civilians. Three of these incidents occurred in the context of heavy fighting in Pekon township, Shan state. Hospitals and clinics were also affected in Chin and Kayin states, and Mandalay and Yangon regions. For example:

- On October 1, a charity clinic and nine houses were set on fire by SAC forces in Mandalay region in a suspected retaliation attack for the assassination of a military administrator the night before in the area. Two civilians were also abducted.

- On October 26, the Pekon Rehabilitation Center, a drug rehabilitation center, was indiscriminately shelled by SAC forces during fighting with the PDF and the Karenni National Defence Force (KNDF). During the attack, displaced civilians sheltering inside the hospital were forced to flee.

- On October 29, a private clinic in Thantlang township, Chin state, was burned to the ground by SAC forces, along with at least 160 homes.

Hospitals and clinics continue to be raided or occupied by SAC forces

During the months of October and November, SAC forces raided at least 13 health facilities in Ayeyarwady, Magway, Sagaing, and Yangon regions, and Chin, Kachin, and Kayah states, resulting in the arrest of 19 health workers. This represents an escalation from the three-month period of July to September, in which eight facilities were raided or occupied. Raids on hospitals or clinics included:

- On October 2, SAC forces raided a hospital in Monywa township, Sagaing region. This occurred during an attack on the civilian population of the town, leading to the destruction of housing and arrests of civilians.

- On October 7, SAC forces entered Pyay Hospital in Pyay township, Bago region and arrested a staff member.

Health facilities are routinely occupied to gain a military advantage or detain civilians. For example:

- On October 12, SAC forces stationed themselves overnight in a hospital during an attack on Lumbang village, Chin state, firing on households and looting private property.

- On November 16, a station hospital in Kayin state was occupied and ultimately destroyed by Border Guard Forces, a local militia aligned with the government. Doctors and nurses had fled the facility in anticipation of the attack.

- On November 16, approximately 40 SAC soldiers and aligned non-state security actors occupied two sub-rural health centers in Ngwe-twin village and Thit-kyin-gyi village, Sagaing region and were seen transporting boxes of weapons into the clinic.

Health Workers

New reports of mass arrests of health workers

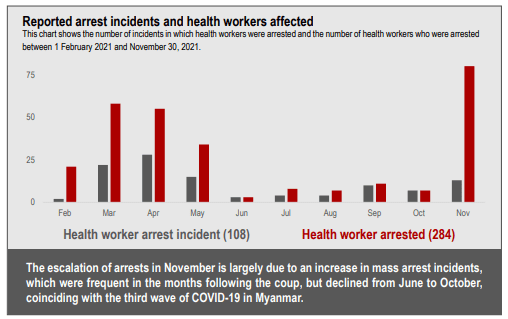

In November, at least 80 health workers were arrested or detained, more than in any month since the beginning of the coup. This escalation is largely due to an increase in mass arrest events, which were frequent in the months following the coup, but declined during the wave of COVID-19 infections. Mass arrests took place during coordinated home raids and at health clinics. In most arrests, health workers have been accused of aiding injured PDF soldiers or being affiliated with the CDM.

Mass health worker arrests included:

- On November 2, ten volunteers with a local NGO that delivered COVID-19 aid were arrested by SAC forces.

- On November 22, a clinic located in a Catholic church in Kayah state was raided by about 200 armed military and police forces, who accused it of being affiliated with the CDM. Eighteen health care workers were arrested and 39 patients receiving treatment at the clinic, including four COVID-19 patients, were forcibly transferred to Loikaw General or Loikaw Military Hospital. The detainees were released on November 23.

Health workers arrested or detained by SAC forces: What is known about their status?

Since the beginning of the coup, at least 284 doctors, nurses and other health professionals are reported to have been served with warrants and arrests.

On October 18, the SAC announced the pardon of 1,316 political prisoners and the dropping of charges against 4,320 political prisoners. However, more than 100 released prisoners were re-arrested shortly after their release. For example, in the Bago region, a male doctor who was released on October 18 as part of the amnesty was rearrested on October 19.

According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, only six health workers, including doctors, a radiologist, and a dentist who were detained or charged with violating penal code 505a, have so far been released as part of this amnesty. All had been held for at least four months. Political prisoners detained at Insein Prison continue to report systemic denial of medical care, which has resulted in disease outbreaks and the deaths of several inmates.

Reports of attacks on military medical personnel aligned with the PDF

The escalation of the conflict has seen increased attacks on medical personnel aligned with the People’s Defense Force (PDF) providing care to civilians. In remote regions of the country with limited access to health care, medical personnel affiliated with local militias often provide primary care to civilian populations. For example:

- On November 16, eight female medics were arrested in a raid by SAC forces on a PDF outpost in Na Gar Bwet village, Kalay township, Sagaing region. The body of an additional medic was later found bearing signs of an execution-style killing at close range.

Health Providers

Escalation in attacks on local NGOs, specifically those providing aid to displaced populations in ethnic minority areas

Delivery of humanitarian aid, including medical supplies, depends on a range of local and international organizations in Myanmar. These organizations are facing ever increasing challenges in delivering essential supplies and services, including destruction of offices and raiding of supplies as well as arrests and violence against staff. There has been an escalation of attacks on these local NGOs, specifically those providing aid to displaced populations in ethnic minority regions such as Chin, Kachin, and Shan states and Sagaing region. For example:

- On November 15, a local NGO was raided by SAC forces in Mandalay. Medical supplies intended for displaced civilians were destroyed and the chairwoman of the organization was arrested.

- On November 15, an aid worker involved in supporting camps for internally displaced people was beaten and arrested by SAC forces in Pekon township, Shan state. He was reportedly killed during interrogation two days later at the 7th Military Operations Command Center in Pekon.

International NGOs and private institutions also face violence. On October 29, SAC soldiers deliberately set fire to the town of Thantlang in Chin state, leading to the destruction of more than160 homes as well as an international NGO office and a private clinic.

Recommendations

Over the past five years, members of the international community have made many commitments to carrying out the requirements of UN Security Council Resolution 2286, which was adopted in May 2016 and strongly condemns attacks on medical personnel in conflict situations.

Many states have formally reiterated their commitments, including in the July 2019 Call for Action to strengthen respect for international humanitarian law and principled humanitarian action, which was signed by more than 40 states. Further, government leaders and humanitarian responders have called for a “COVID ceasefire” in the name of regional and global health security.

We join the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar in calling on the UN Security Council and all member states to invoke Resolution 2565, which demands that “all parties to armed conflicts engage immediately in a durable, extensive, and sustained humanitarian pause to facilitate the equitable, safe and unhindered delivery and distribution of COVID-19 vaccinations in areas of armed conflict.”

It is imperative that COVID-19 measures are maintained in light of the new Omicron variant and continued obstruction of healthcare delivery. The increased transmissibility of Omicron raises concerns about potential outbreaks in prisons and interrogation centers, and among displaced populations, particularly in conflict zones.

Vaccines and boosters must be made available and accessible to all civilians, be it through the government, NGO clinics, or private facilities.

All UN member states should:

- adhere to the provisions of international humanitarian and human rights law regarding respect for and the protection of health services and the wounded and sick, and regarding the ability of health workers to adhere to their ethical responsibilities of providing impartial care to all in need;

- ensure the full implementation of Security Council Resolution 2286 and adopt measures to enhance the protection of and access to health care in situations of armed conflict, as set out in the Secretary-General’s recommendations to the Security Council in 2016;

- strengthen national mechanisms for thorough, impartial, and independent investigations into alleged violations of obligations to respect and protect health care in situations of armed conflict and for the prosecution of the alleged perpetrators of such violations; and

- facilitate the unhindered delivery and distribution of COVID-19 vaccinations, medication, and supplies in areas of armed conflict, as called for in UN Security Council Resolution 2565.

Non-state actors should:

- adhere to the provisions of international humanitarian and human rights law regarding respect for and the protection of health services and the wounded and sick, and regarding the ability of health workers to adhere to their ethical responsibilities of providing impartial care to all in need; and

- sign the Deed of Commitment on protecting health care in armed conflict and ensure compliance with its principles.

Data collection

- This document was prepared from information compiled by Insecurity Insight, Physicians for Human Rights, and the Center for Public Health and Human Rights, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. It is drawn from credible information that is available in local, national, and international news outlets, online databases, and social media reports.

- The incidents reported are neither a complete nor a representative list of all incidents. Most incidents have not been independently verified and have not undergone verification by Insecurity Insight, Physicians for Human Rights, or the Center for Public Health and Human Rights, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

- All decisions made on the basis of or in light of such information remain the responsibility of the organizations making such decisions. Data collection is ongoing and data may change as more information is made available.

- To share further incidents or report additional information or corrections, please contact info@insecurityinsight.org.

This document is funded and supported by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) of the UK government through the RIAH project at the Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute at the University of Manchester, by the European Commission through the “Ending violence against healthcare in conflict” project, and by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Insecurity Insight and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, the U.S. government, the European Commission, the FCDO, or Save the Children Federation, Inc.