Executive Summary

A Child Rights Crisis

Policy debates rage over what has been termed a humanitarian crisis, a human rights crisis, or a national emergency at the U.S.-Mexico border. What is clear is that it is a child rights crisis. Unaccompanied children, adolescents, and young families have fled in increasing numbers from violence in the “Northern Triangle” countries of Central America – El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras – and have been met at the U.S. border with harsh and punitive policies which violate their rights and compound existing trauma, thereby threatening the health and well-being of thousands. These policies are justified in the name of deterrence.[1] However, if persecution and violence are the primary factors influencing migration, harsh border enforcement will not serve as an effective deterrent and will only cause more harm to an already traumatized population.[2]

Though high levels of child migration have captured the national attention, there has been comparatively little medical research in the United States about child asylum seekers’ trauma experiences and resulting negative health outcomes. However, the limited number of studies of immigrant and refugee children who have resettled in developed countries have identified a high rate of trauma exposure and high rates of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, chronic pain, musculoskeletal injuries, scars, and neuro-cognitive problems.[3] The aim of this study is to provide the first detailed case series of recent child and adolescent asylum seekers in the United States.

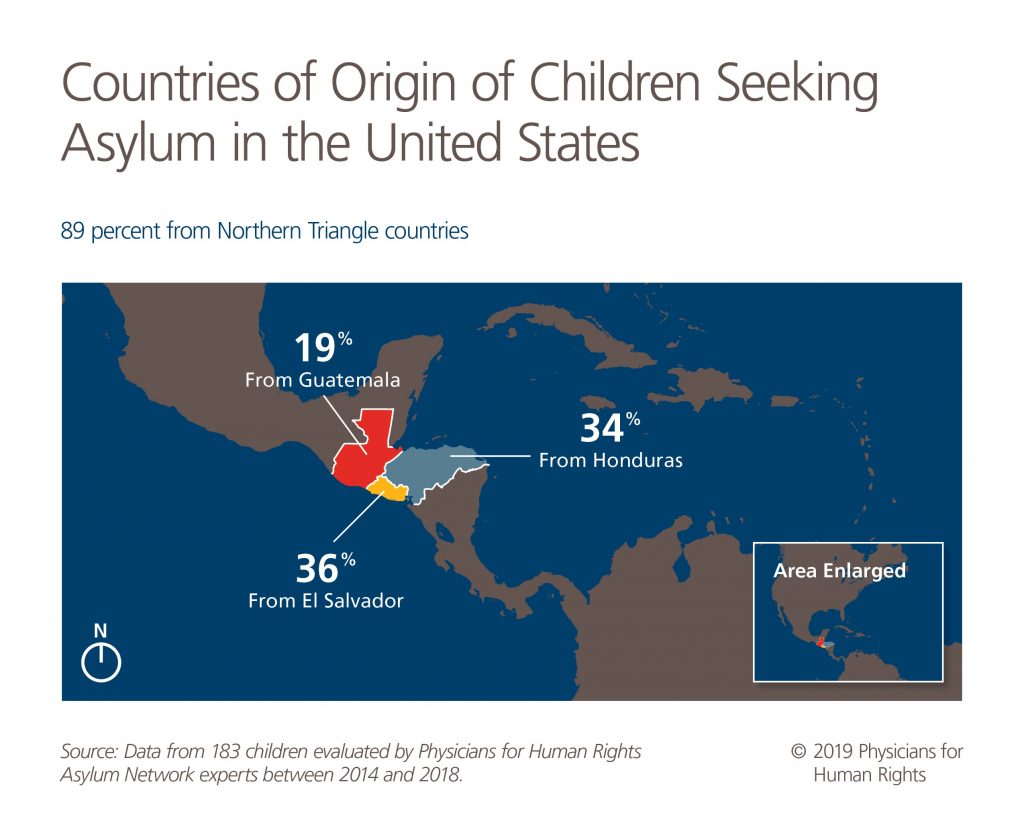

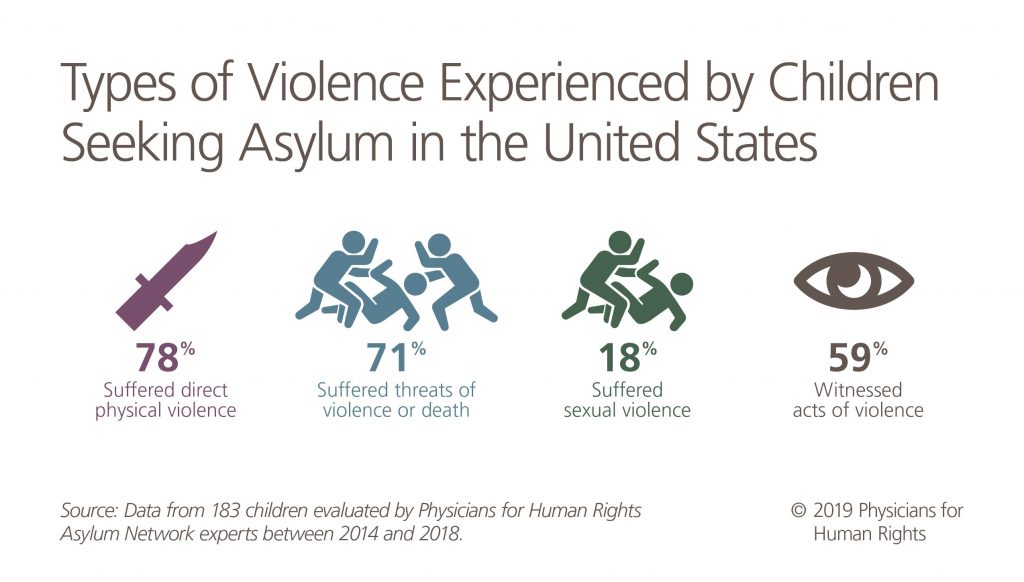

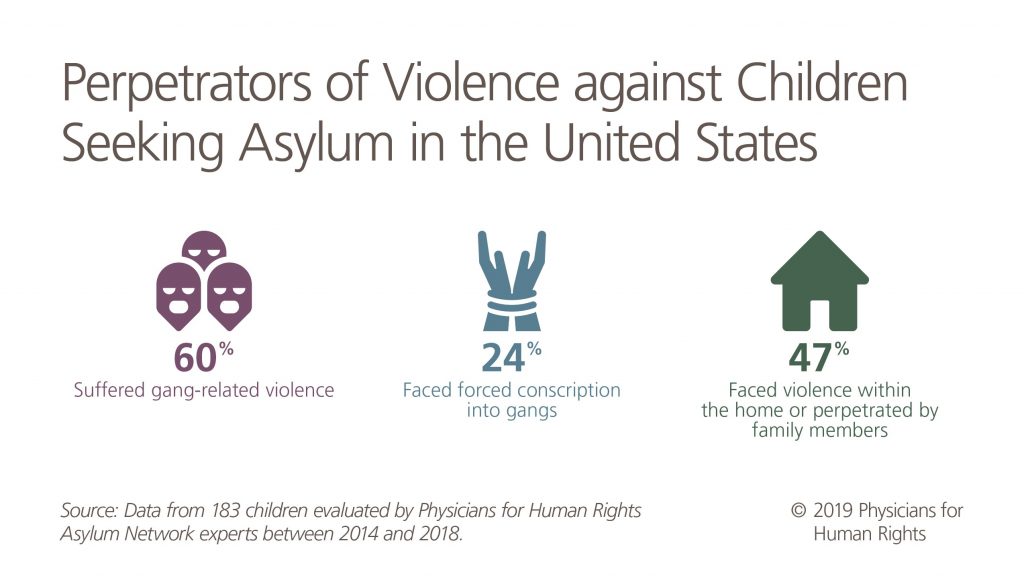

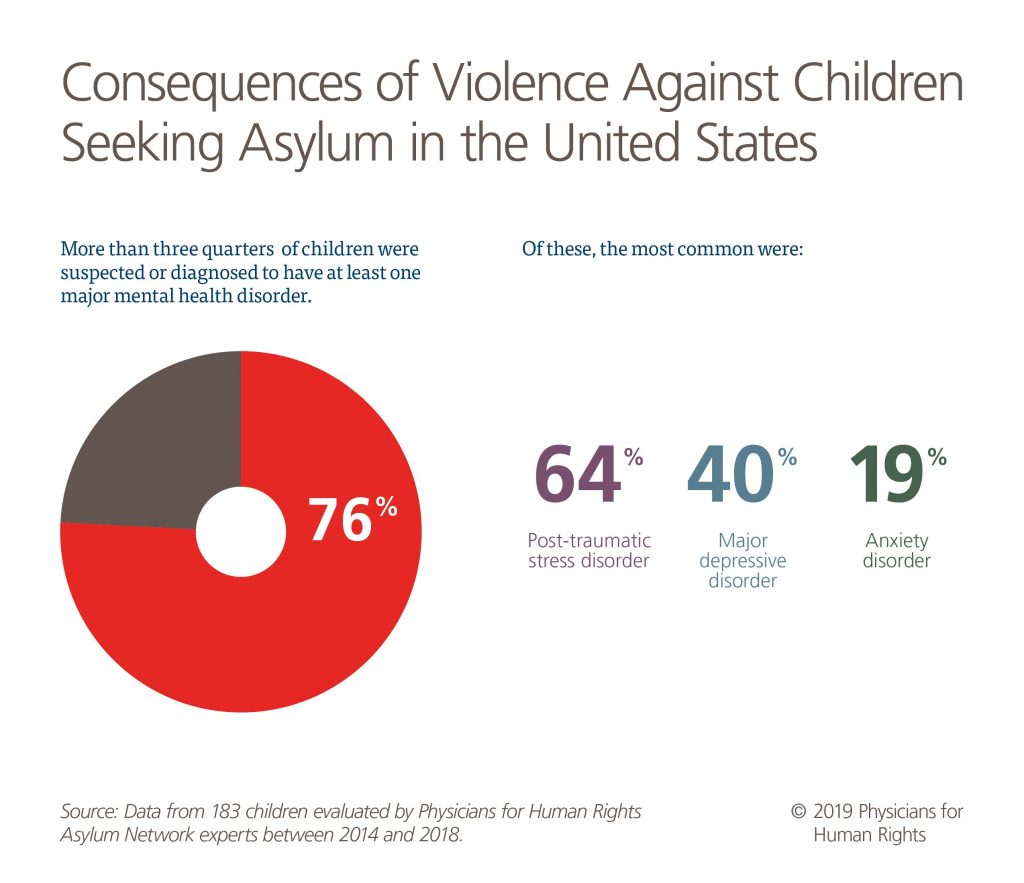

This report communicates the findings from more than 180 physical and psychological evaluations of children seeking asylum in the United States. The evaluations were conducted by members of the Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) Asylum Network between January 2014 and April 2018 and were analyzed by medical school faculty and students from Weill Cornell Center for Human Rights. The vast majority of the children evaluated were from the Northern Triangle countries (89 percent), of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Children reported that they survived direct physical violence (78 percent) and sexual violence (18 percent), threats of violence or death (71 percent), and witnessing acts of violence (59 percent) in their home countries. This violence was most often gang-related (60 percent), but a significant portion of children (47 percent) faced violence perpetrated by family members. PHR’s clinicians documented negative physical aftereffects of this abuse: from musculoskeletal, pelvic, and dermatologic trauma to severe head injuries. 76 percent of children were suspected to have or diagnosed with at least one major mental health issue, most commonly post-traumatic stress disorder (64 percent), major depressive disorder (40 percent), and anxiety disorder (19 percent). Furthermore, children reported that government authorities in their home countries did not effectively prevent, investigate, prosecute, or punish crimes against children.

These findings document that children arriving in the United States are fleeing severe forms of harm which may amount to persecution if their home government is unable or unwilling to control the perpetrators, and if their persecution is based on their race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. Asylum jurisprudence in the United States and internationally recognizes that gang and domestic violence may amount to persecution. In accordance with international and U.S. law, individuals with a credible fear of persecution arriving at the U.S. border have the legal right to apply for asylum. International and U.S. law also prohibit the return of any individual to a country where they face persecution, torture, ill-treatment or other serious human rights violations, with children deserving heightened consideration.[4] Child asylum seekers are also entitled to additional protections under international and U.S. law, including accommodations in the asylum process which take into account their level of development and maturity and their specific health and mental health needs. The right of children to be heard and to remain with their parents, as long as it is in their best interest, is recognized as a civil and political right.

The findings in this report and the relevant legal standards demand an effective and humane policy response both in countries of origin, to prevent the violation of child rights, and in the United States, to fairly recognize claims of persecution and end practices that expose these young migrants to further trauma. PHR calls on countries of origin to urgently direct resources to end impunity and protect children. As a priority, governments must ensure adequate resources to investigate, prosecute, and punish violent acts against children, and establish or maintain independent investigatory bodies to address corruption and impunity. Governments must also ensure adequate resources for violence prevention and response, such as specialized police units, education initiatives, and specialized assistance for child survivors. Given the extreme levels of violence experienced by the children from the Northern Triangle evaluated by PHR, the U.S. administration must safeguard access to asylum in the United States, in order to meet immediate needs for protection and to maintain vital aid to Northern Triangle countries for addressing violence and instability in the long term. Since children’s health has been affected by repeated trauma exposure, the administration should ensure that all children receive pediatric medical screening upon arrival at custody and uphold child protection standards in custody, prioritizing least restrictive settings and increasing use of alternatives to detention.

Children arriving in the United States are fleeing severe forms of harm.

Background

Rising Numbers of Children and Families Seek Asylum in the United States

Since 2010, U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions of border crossers in the southwest sector of the U.S. border have hovered between 300,000 and 450,000 per year, much lower than in the past three decades, when apprehensions frequently exceeded one million.[5] However, the demographics of the border-crossing population changed in 2014. The number of children and adolescents arriving at the U.S. border rose dramatically, both in numeric terms and as a percentage of the overall number of border crossers, a wave of displacement known as “the surge” and now called by some a “national emergency.” The number of unaccompanied children (zero to 17 years old) apprehended increased from 16,000 in FY2011 to 50,000 in FY2018 (from five percent to 13 percent of total apprehensions),[6] and the number of families rose from 15,000 in FY2013 to 107,000 in FY2018 (from 3.5 percent to 26 percent of total apprehensions).[7] The number of teenagers crossing alone peaked in 2014 but is still high, while the number of families with younger children has remained consistently high for several years. Combined, these groups comprise almost 40 percent of apprehensions in FY2017 and FY2018.

Basic trends in U.S. asylum statistics indicate that the demographic increase in the number of children and families seeking asylum is due to people fleeing high levels of violence in Central America, rather than labor migration. The majority of individuals that Border Patrol has apprehended at the border are from the Northern Triangle countries, which have some of the highest rates of homicide in the world, resulting in epidemic levels of domestic, gang, and gender-based violence.[8] The number of applications for asylum in the United States increased more than seven-fold from FY2009 to FY2013, and 70 percent of that increase was due to asylum applications from the Northern Triangle.[9] From 2012 to 2017, affirmative asylum applications from individuals from Central American countries rose again from 3,523 to 31,066, an almost eight-fold increase, with unaccompanied children comprising 66 percent of applications in 2015 and 56 percent in 2016 and 2017.[10] Asylum grant rates have also increased, which speaks to the validity of rising requests for international protection: 2010 to 2016 saw a 96 percent increase in the percentage of asylum seekers from the Northern Triangle who were granted protection.[11]

Family Separation and Child Detention Increase Health Risks

As early as March 2017, the U.S. government began physically separating thousands of children from their parents at the border, detaining them hundreds or thousands of miles apart, without tracking them or planning for their reunification.[12] This practice was implemented in spite of medical evidence that demonstrated how separation from parents increases the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder and depressive disorders in children, resulting in a negative impact on the cognitive and emotional functioning which can continue into adulthood.[13] The Trafficking Victims Reauthorization Act has substantial protections to ensure that children are screened and separated from traffickers posing as family members at the border, and, in the class action lawsuit won on behalf of the separated families, the government did not provide evidence of a security risk to the children to justify the separations.[14] Following a court injunction prohibiting further family separation,[15] the administration sought other punitive measures to deter children and families from seeking safety in the United States, as part of a return to the Consequence Delivery System known as the Zero Tolerance policy.[16] These measures included seeking to authorize indefinite detention of children in unlicensed facilities.[17] The administration detained thousands of children in a massive tent city[18] and targeted potential sponsors – to whom children could be released – for enforcement action, which resulted in a significant increase in the population and duration of child detention.[19]

Medical experts warned that the overall rise in numbers of detained children was vastly increasing the risk of serious health harm due to the dangerously inadequate conditions of confinement.[20] In December 2018, two children died in U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Customs and Border Protection (CBP) custody[21] and in May 2019, a 16 year old died in CBP custody and a two year old died, released on his own recognizance from CBP detention.[22] However, in February 2019, DHS was still holding an increased number of infants in detention, some for longer than the maximum 20 days stipulated in a 1997 court ruling, the Flores settlement agreement.[23] Research has shown that alternatives to detention are cost effective, humane, and contribute to improved health outcomes.[24] However, the Trump administration shut down the Family Case Management Program, which enabled families with children to remain in the community while their immigration proceedings were pending, with compliance rates of over 99 percent of families attending immigration court hearings and appointments.[25]

Recent Asylum Law Developments Threaten Access to Asylum

Despite indications that violence in Central America is a driving factor in the rise of asylum seekers arriving at the border,[26] the U.S. government has increasingly resorted to policies and practices which limit the right to seek asylum at all, such as “metering” at ports of entry, which requires asylum seekers to wait in a queue for weeks or months before being admitted for inspection.[27] The U.S. government has also implemented an unprecedented turn-back policy by which asylum seekers must wait in Mexico while their asylum case is considered, which puts them in danger of persecution in Mexico and limits their access to legal counsel for their asylum case.[28] Given the levels of violence reported by children in this study, these restrictive policies unacceptably block timely access to asylum procedures and put children in danger.[29]

Emerging displacement trends indicate that gang violence and domestic violence are among the most prevalent forms of persecution reported by asylum seekers in the United States, including children arriving from Central America.[30] Since gang violence and domestic violence can amount to persecution by non-state actors which the government is unable or unwilling to control, extensive domestic and international jurisprudence recognize the validity of asylum claims based on domestic violence and gang violence.[31] In March 2018, then Attorney General Sessions questioned whether domestic and gang violence survivors may be considered members of a “particular social group,” an essential element in an asylum claim, seeking to disqualify these individuals from claiming a credible fear of persecution.[32] However, Sessions’ decision was reversed in December 2018, when the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia issued a permanent injunction, finding that the Attorney General’s policy violated the Immigration and Nationality Act.[33] This ruling reaffirmed that, in line with decades of domestic legal precedent, domestic violence and gang violence survivors have the right to apply for asylum if they express a credible fear of persecution.

Methodology

PHR Asylum Evaluations and the Istanbul Protocol

Members of the Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) Asylum Network collectively conduct approximately 600 forensic evaluations annually for asylum seekers involved in U.S. immigration proceedings.[34] These medical-legal affidavits are requested by attorneys who identify a need to document sequelae (aftereffects) that their clients exhibit as a result of physical and psychological trauma from torture or persecution. The declarations are conducted in accordance with the principles of the Istanbul Protocol,[35] the international standard endorsed by the United Nations to assess, investigate, and report alleged instances of torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment. They are submitted to the Department of Homeland Security’s United States Citizenship and Immigration Services and the Department of Justice’s Executive Office of Immigration Review by PHR Asylum Network members to highlight the degree of consistency between the client’s account of persecution and their physical signs of injuries and psychological symptoms.[36] Although these evaluations alone cannot determine asylum claims, they document severe health and mental health harms experienced by the client, in order to assess whether or not the severity threshold for persecution has been reached. Other essential elements needed for the asylum case, such as determining discriminatory intent of persecutors or failure of the state to control persecutors, are not directly addressed in these affidavits. At times, collateral information in the affidavits may be present related to those elements of the asylum criteria.

Data collection and analysis

In preparation for the current study, PHR Asylum Program staff ran a search in the program’s case management database for the following inclusion criteria: juvenile cases with individuals age 18 or under that received forensic evaluations from PHR Asylum Network members from January 2014-April 2018 and in which full consent for the use of de-identified data for research and advocacy was obtained. At the time of the study’s conceptualization, 368 evaluations of asylum seekers under the age of 18 had been conducted. However, the program had only collected 18 completed affidavits. Program staff contacted the clinicians responsible for the remaining 350 completed affidavits to solicit redacted copies, finally reaching 183 affidavits in total. This sampling method excluded cases with individuals aged 19 years or older at the time of evaluation, cases that had incomplete or missing medical-legal affidavits, and cases in which consent was not obtained for the use of de-identified data. PHR staff redacted the corresponding affidavits of all cases that met the inclusion criteria for identifying personal information and stored them on PHR’s password-protected database.

The Cornell Institutional Review Board reviewed the research plan and approved compliance with Title 45 CRF part 46 provisions for protection of human subjects.

The co-investigators jointly developed a coding tool after reading the affidavits. Sources for the coding categories included United Nations protection assessments and validated clinical assessment tools, such as the Hopkins Symptom Checklist and PTSD Civilian Checklist. PHR staff carefully read through the affidavits to ensure that all were fully de-identified and stripped of their case numbers, with new study numbers assigned to each affidavit. Weill Cornell Center for Human Rights faculty and students coded the data using a standardized instrument capturing basic demographic information, trauma exposure history, vulnerability factors, and medical and mental health outcomes. They then entered data into a secure database using Qualtrics. The investigators also conducted a qualitative analysis of summarized trauma narrative notes entered into the coding tool using a quasi-grounded theory approach to describe emergent themes within the data and identify representative narratives and quotes. The members of the research team independently analyzed each trauma narrative in the affidavit, selecting direct passages and quotes, coding key concepts, categories, and themes/sub-themes through a process of open, axial, and selective coding. Members of the research team grouped text supporting each component and reviewed the initial individual coding results. Through an iterative and consensus-based process, the research team revised themes and sub-themes.

Limitations

This data was not collected uniformly for the purpose of research, because each individual evaluation was developed for use in the specific legal case of the client.

Due to PHR’s program modality, the study considered only child and adolescent asylum seekers with legal representation: it does not capture the experiences of children applying for asylum without an attorney (Nineteen percent of children whose cases began in FY2018 and 23 percent of children whose cases began in FY2019 have no legal representation in deportation proceedings[37]). There were very few detained child and adolescent asylum seekers included in the data set, which means that the findings do not focus on compounded and exacerbated trauma experienced by young detainees.

Finally, although many crossed the border as unaccompanied minors, most of the children and adolescents were reunited with family members prior to the evaluation. Thus, further study is needed regarding the specific experiences of unaccompanied children who do not join family members in the United States, as well as children crossing the border with their families.

Overall, generalizability is an issue with any type of research. Both qualitative and quantitative measures have value in terms of characterizing trauma exposure and health outcomes, just as they have their limitations. The sample in this study is not a representative sample of all child and adolescent asylum seekers in the United States. However, when considered with other available evidence (known to be limited by a lack of appropriate intake processes, health screening, government transparency, and overall inaccessibility of this population), this data seems to support trends of high rates of violence and trauma experienced by children fleeing the home countries represented in this samples.

Findings

Introduction

The following accounts of children are taken from forensic evaluations completed by Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) clinicians who are experts in documenting trauma and persecution. For the purpose of accuracy, quotations are taken directly from the clinicians’ expert affidavits. Direct quotations from children are only included if present in the clinician’s evaluation.

Evaluations for 183 individuals were included in this analysis, including 114 male and 69 female asylum applicants, with an average age of 15 at the time of evaluation. The vast majority – 89 percent – were from the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador (36 percent), Guatemala (19 percent), and Honduras (34 percent). Due to the evaluation’s focus on pre-migration trauma, the child’s experience in crossing the border is not mentioned in 50.5 percent of cases. However, out of the 49.5 percent of cases in this data set that mention the border crossing experience, 67 percent of those children crossed the U.S. border as unaccompanied children.[38]

The analysis which follows describes children’s experiences of violence and harm through the major analytical categories presented by the data: gang violence, sexual violence (perpetrated by both gang members and family members), and domestic violence, which can become implicated in gang dynamics. These three categories overlap considerably but are distinguished in order to identify descriptive characteristics of each. The children’s accounts also demonstrate repeated failure by states to protect children from harm and to prosecute and punish perpetrators of crimes against children. Separation from parents in the country of origin due to migration seems to increase children’s risk of abuse. Though the study primarily focuses on the abuses experienced in the children’s home countries that motivated their flight, some children also mentioned undergoing harm during transit and as a result of U.S. border and immigration enforcement, which exacerbated and compounded the harms they had already experienced. Finally, the study includes an analysis of the physical and psychological consequences or manifestations of trauma, as well as resilience factors in children. The findings are followed by an overview of the legal framework and policy recommendations, which suggest approaches to prevention and accountability for the human rights abuses described by the children.

Children Suffered Multidimensional, Recurrent, and Sustained Trauma

Complex trauma, as compared to acute or chronic trauma, involves exposure to multiple severe and pervasive events which have negative long-term effects.[39] The children evaluated experienced multiple forms of both direct and indirect trauma. A significant majority – 78 percent – suffered direct physical violence, and 18 percent were subjected to sexual violence. Nearly three quarters (71 percent) were threatened with violence or death (71 percent), and 59 percent witnessed acts of violence. Most of the violence the children experienced was gang-related (60 percent), but a significant portion of children (47 percent) faced violence within the home or perpetrated by family members, which prompted them to flee alone or accompanied by other family members. Additionally, children were vulnerable to other forms of deprivation and harm, including neglect, lack of access to primary education, homelessness, and child labor.

All of these events constitute adverse childhood experiences, which have been strongly linked to a wide range of lifelong negative physical and mental health outcomes.[40] The health impacts of these experiences were further mediated by factors such as poverty and parental separation or death.

A lack of effective intervention from government authorities in their home countries to prevent, investigate, prosecute, and punish crimes against children was a major theme of the children’s stories. The report describes the leading categories of trauma exposure, other vulnerability factors, and negative health consequences experienced by this group of children.

The statistics in this report show that these children not only experience high rates of trauma, but often are subjected to multiple forms of trauma by multiple perpetrators. These results add additional context for the severe abuse described by the qualitative findings.

Gang Violence Terrorizes Communities

“I saw the four of them in their caskets, I never imagined to see them with shots all over their faces. I thought they were shot only once but their whole faces were shot with bullets.”

A teenage boy recalling the image of his murdered brother, aunt, uncle and cousin

A majority of children and adolescents assessed were victims of violence at the hands of gang members (60 percent) or forced conscription into gangs (24 percent). Gang members perpetrated repeated physical assault and beatings, sometimes aggravated assault with weapons including sticks, belts, bats, knives, machetes, and firearms, resulting in serious injuries. One young woman “reports having been beaten all over her body including her head, being dragged through the woods, being tied to her friends, blindfolded and raped by multiple people.” Another young boy describes a series of repeated attacks from gang members, including an attack with a machete “leaving a deep wound on his left knee,” being “cut with a knife,” a gang member “forcefully pulling his left arm behind his back and pushed him to the ground…his shoulder became painful and swollen, purple and painful to move” from a traumatic shoulder dislocation, cigarette burns to his arms, and repeated trauma from punches and kicks to his body.

Additionally, children often witnessed brutal acts of violence against their own families or members of their communities. Witnessing violence is a traumatic event which results in serious negative mental health outcomes for children.[41] One teenage boy recalled the image of his brother, aunt, uncle, and cousin in their caskets: “I saw the four of them in their caskets, I never imagined to see them with shots all over their faces. I thought they were shot only once but their whole faces were shot with bullets.”

Another boy described a memory “seared into [his] brain. At 16, he came upon a decapitated head whose face had been peeled off intact and placed next to the head. This horrific sight caused nausea as well as a growing and persistent sense of fear. This image often intruded into his nightmares.” Gangs often used shocking tactics to incite fear, or as a warning to those attempting to resist. One young woman described her brother-in-law’s brutal murder: “His body had been discovered in the very location she was supposed to deliver [his] children. His body was dismembered and had been put in several different bags, his hands and feet were tied and he had been severely beaten…. She continued to receive threats for over a year after his murder.”

Children reported that the gangs forced them to choose between joining the gang and being murdered.

Children reported that the gangs forced them to choose between joining the gang and being murdered. One boy refused to join the gang, so the gang members took him into the woods and beat him on the head and body with their fists and with rocks until he was unconscious. If children did join the gang, the coercion continued with the demands of the gang. A 16-year-old described how he was faced with an ultimatum to kill his uncle and anyone else in the uncle’s household: “Kill them or you die.” When he found his uncle’s daughter and pregnant wife in the home, “he knew that it would be wrong to kill those children or to leave them without a father so he just could not do it. Instead he greeted the girl and kissed her on her head and left. He went to his girlfriend’s home and held his newborn son. Holding the boy in his arms, he knew he had to change because the life he was living was not one in which he wanted to bring a child.”

Children reported gang members kidnapping them, holding them hostage, or enslaving them. One young girl explained her terror after being kidnapped, “feeling like at any moment the gang would come pick her up and kill her and her family. She described eating and sleeping very little, waking up at night in a panic. She described being unable to close her eyes, and breathing very quickly.” Another young girl who was kidnapped by a gang member describes her brutal ordeal. Her kidnapper “repeatedly raped, beat, and terrorized her over the course of the next 3 years. He forced her to collect money from people, allowed her to be raped and beaten by other gang members, and threatened to kill members of her family if she ran away. He made her pregnant twice and at one point drugged her and tattooed his name on her back.”

[A] young girl … was kidnapped by a gang member [who] repeatedly raped, beat, and terrorized her over the course of the next three years. He forced her to collect money from people, allowed her to be raped and beaten by other gang members, and threatened to kill members of her family if she ran away.

The geographical reach of the gangs extended to private homes and community spaces, giving the feeling that nowhere was safe. One boy detailed his encounter in a grocery store during which a “man grabbed his hand and quickly cut the 5th digit of his left hand with a machete as ‘a warning,’ indicating that if he did not join the gang he would ultimately be killed.” Gangs also used social media to make threats and assert their sphere of influence. One boy reported that even in the United States, gang members on Facebook threaten to kill him if he ever returns to El Salvador. Since arriving in the United States, a girl continues to receive threats of physical harm on Facebook from gang members who wanted her to be their ‘girlfriend,’ saying they will look for her and find her if she returns.

Children Targeted for Sexual Violence

Almost 20 percent of the children evaluated by PHR experts experienced brutal and repeated sexual violence or exploitation, including rapes that resulted in adolescent pregnancy. Children described being kidnapped, exploited, and trafficked for sex. One girl told the PHR clinician that she did not tell her mother about the gang rape, telling her instead that she migrated to the United States out of a desire to study, because she was worried about her mother’s safety.

Much of the violence perpetrated by gang members was sexual in nature, ranging from coercion to become the ‘girlfriend’ of a gang member, to subjecting children to brutal group assaults. One young woman described her experience being gang raped: “When she refused [to have sex with gang members], multiple of the gang members raped her and told her they would hurt her mother and father if she continued to refuse…. She recalls having a severe headache, vaginal bleeding, and pelvic pain for approximately one week.”

Children reported sexual violence committed by family members. One girl described the devastating rape by her cousin as “he started to choke her and then pushed her onto a bed…. He pushed her arms back over her head and raped her. She states that she stopped fighting back at some point so he would stop hitting her.” A young boy described a time “when he was four or five, an uncle he was staying with, who he hardly knew, summoned him and his brother to join him in the shower and was made to touch his genitals under threat of killing his sister.” Another girl described sexual assault committed by her mother’s boyfriend, who groomed her for touching, nude photos, forcing her to perform oral sex, and finally vaginal penetration. “Even though she detested everything [he] made her do to and with him, [she] felt unable to say anything to anyone because [he] threatened to take her away from her family and said that he would force her to do things that she did not want to do. Her family was completely unaware of the daily sexual assault that was occurring while they were out of the home.”

These acts of sexual abuse and assault, especially when experienced at such a young age, lead to lasting trauma, often manifested as feelings of dissociation, impaired psychological development and self-image, and social isolation. A 17-year-old girl described how her rape at age 13 affected her. She said, “I continued walking to school but I felt like it wasn’t really me walking. I felt like it was someone else outside of my body. I felt that everything was different, I didn’t ever want to be with the other girls. I felt that they were little girls and I was not.”

Domestic Violence Normalized

Child abuse is so common that even when a beating resulted in an open cut that required many stitches, no one at the local health facility asked any questions about how the injury happened.

Nearly half of the children in this study (47 percent) reported experiencing violence in the home or at the hands of family members. Children often reported their parents as perpetrators of this abuse, as well as other family members or caretakers including aunts, uncles, grandparents, or older cousins. In addition to the acts of sexual violence described earlier, children reported that family members attacked them physically and subjected them to verbal and emotional abuse. The children evaluated by PHR fled their abusers, either alone or with other family members.

Reporting violence and abuse was dangerous for children, as it could anger their abusers. One girl reported her punishment after a diary detailing her abuse was found: her grandfather burned her with molten pieces of plastic, resulting in severe, painful burns and lasting scars on her legs. Due to the prevalence of violence in some communities, abuse became normalized in community structures. A 16-year-old girl reported that child abuse is so common that even when a beating resulted in an open cut that required many stitches, no one at the local health facility asked any questions about how the injury happened. However, gang members in town knew about the abuse that she was suffering and repeatedly offered to help her “take revenge.” Gangs may perpetrate cycles of violence, as domestic abuse cases become gang-involved. Gang members told a 16-year-old boy that he must kill his uncle because, since everyone in the community knew that the uncle had abused him when he was a child, not vindicating the act would make the gang look “weak.”

Domestic violence was also linked with homelessness, as some children were forced to leave their homes by family members. One child reported squatting in an abandoned house in a neighborhood with high gang activity after feeling unsafe in her home, leaving her vulnerable to being targeted. “One night, when she was staying alone at the house, a man from one of the gangs came by. There were no locks on the door, and she was too frightened to move, so she just lay in her bed, very still, hoping he wouldn’t find her. He found her in the bed, and he raped her. Afterwards, he threatened her, saying that he would kill her.”

Abuse by caretakers is deeply confusing for children, since, as authority figures, caretakers should help children grasp normal behavior; abusive treatment prevents children from properly interpreting the world around them. One boy explained that when his grandmother beat him, “he would space out in a dissociative manner …; he would effectively leave his body as though he were watching himself getting hit. He would wonder, ‘Am I bad?’ in an effort to make sense of the beatings…. He believes that if he’s getting hit it must be because he is bad.”

Children were often punished severely for developmentally normal acts, such as bedwetting or doing housework incorrectly. One girl described how her father would check each night to see if she had wet the bed and, if she had, he would violently pull her out of bed, take her outside, and beat her with his hands, belt, and rubber sandals. Her mother and siblings witnessed the abuse but felt too afraid to stop him. A boy described how he and his brother were both forced to kneel for hours on spikes while their arms were tied behind their backs and burned with a hot knife for not completing chores.

Abused and mistreated children also experienced deprivation and neglect, often manifesting in food insecurity and hunger, homelessness, disenrollment in school and lost access to education, and labor exploitation. One child described living with a physically and verbally abusive father who repeatedly attacked and mistreated him and his siblings. “He continued to beat them with his hands, feet, and belts. He also deprived them of food, spending his money on alcohol, so they regularly showed up to other family members’ homes for meals.” Another child described that his grandparents “would hit [him] and yell at [him]. After being hit, [he] was often forced to gather wood and was not fed.”

Many children were forced to drop out of school due to lack of safety in the community and at school, parental neglect, forced child labor, and exploitation. One girl stopped attending school altogether for about a year after a gang had threatened to tie her brother to a chair and make him watch while she and her sister were raped and murdered. There were a lot of gang members around the school and she felt watched. One 12-year-old boy reported that he stopped attending school because his father forced him to work in corn fields and care for livestock. He was repeatedly told that he was “worthless” and hit with belts and cables. During this child’s forensic evaluation, the evaluator observed that he became very quiet and stared at the floor. When asked if he was alright, he said, “Not really, I am reliving the whole experience.”

States Fail to Protect Children

“I saw that one of my cousins had been shot in the stomach by the police. He was nine. After my cousin was taken to the hospital, [t]he police officer asked

17-year-old boy from Honduras

me and my family where he was so he could finish him off.”

Children articulated a consistent failure of state protection. Although children may be less likely than adults to report crimes to the authorities due to their less developed understanding of government structures, children in this study repeatedly described situations where government authorities actively abused children, failed to effectively protect victims, did not investigate crimes, and did not prosecute or punish perpetrators.

Direct Police Brutality Against Children

Some children reported experiencing or witnessing direct police brutality against children. One boy detailed his family’s experience with the local police, recounting a nearby shooting: “We lived on one street and on the other street we heard all the gun fire that was happening. I saw that one of my cousins had been shot in the stomach by the police. He was nine. After my cousin was taken to the hospital, [t]he police officer asked me and my family where he was so he could finish him off.” Another was sexually assaulted. She was able to identify her attacker and was assigned a detective, who she at first believed was helping her. He told her that he was taking her to see a psychologist who could “erase” everything that happened to her, but instead he took her to a hotel and sexually assaulted her. In another case, after seeing the body of a murdered taxi driver, one boy described his predicament: “The police themselves were corrupt, offering no protection for the citizens but rather engaged in violence and extortion themselves. [He] was both terrified of the police and fearful of retaliation if he cooperated.”

Children reported that some police officers committed or threatened violence in order to extort bribes. The police either demanded money to file a report or robbed the victim. In one case, “the police detained [a boy] on false charges for about two hours. During this incident, the police beat him and stole his possessions before releasing him to his mother.”

Gang Intimidation and Infiltration into the Police

A common pattern related to the failure of state protection is gang intimidation of the police and gang infiltration into the police. Reporting or being thought to have reported crimes to the police brings down swift gang retaliation. One girl explained that “if people reported gang-related crime to the police, they would be very slow to arrive at the scene of the crime or to file reports. The police were scared of the gangs, hence the gangs controlled most of what happened in the town.” One girl realized that her boyfriend was involved in a gang when she found pistols hidden in the house. When she confronted him, he threatened to kill her if she told anyone. The girl told the PHR clinician that her boyfriend’s gang was affiliated with the police and if she had tried to tell the police, they would simply have informed her boyfriend, putting her in danger.

In a case of gang infiltration, a police officer accused a boy of being a member of the MS-13 gang and hit and kicked him to force him to admit to gang membership – then, the same police officer told the boy that he (the police officer) was a member of the rival 18th Street gang. As the boy walked home after the beating, members of the MS-13 gang physically assaulted him, suspecting that he had spoken to the police officer about their activities. The boy told the PHR clinician that he considered reporting the police officer but decided not to because his family was afraid that they would not be protected from reprisals. A girl reported that her family was targeted after her stepfather told the police about seeing bodies dumped in the river; in retaliation, gang members came to her home and raped her. Her family fled the country shortly afterwards without reporting the assault, having understood that the police were providing information to the gang. Another boy mentioned that he never even approached the police after receiving death threats for refusing to join a gang, since the police were known to collaborate with that gang.

“The police themselves were corrupt, offering no protection for the citizens but rather engag[ing] in violence and extortion themselves.”

A boy recounting his dilemma after seeing a murdered taxi driver

Failure of Police to Respond Despite Knowledge of Crimes

In other cases, the children reported that the police failed to take action, despite knowing about crimes committed against children. In one case, some boys, including the client’s brother, were kidnapped, tortured, and killed due to inter-gang violence. Despite knowing about the murders, the police did not investigate or make efforts to protect other children; they simply warned the client that he could be the gang’s next target.

One girl reported knowing from early childhood that the police in her country never protected girls or women in her neighborhood – she knew they would not come to the scene when crimes were committed and that they did not enforce laws against gang violence. A brutal gang rape occurred at a soccer game in her town, but the police, fearing the gang, did not investigate or make any arrests. The girl remained indoors for weeks, saying, “I was terrorized with fear that something could happen to me, that I would be the next victim.” Said another girl, “The police are far away and in any case do nothing to help. There is no one else in the town to call for help.” One young girl’s sexual assault by her grandmother’s husband was videotaped by a neighbor, who tried to use the video to blackmail her into sex. When she refused, the neighbor circulated the video in the community, and she was stigmatized and blamed by community members for the abuse; “It was generally known and accepted as a matter of course that the police would do nothing about cases such as hers.”

Even when child victims or their parents try to pursue legal action to protect the children, the system is ineffective. An eight-year-old girl explained the authorities’ reaction when her family reported that she had been sexually assaulted: they refused to investigate and “even became angry that they were ‘bothered’ about something like childhood sexual abuse.” Another girl described a time when she tried to call the police for protection from her abuser. The police came to the scene, but instead of helping her, they told her to “take care of [her] family problem.” In one case, a daughter told her mother that the mother’s boyfriend was sexually abusing her. Her mother believed her, forced him to leave the house, and filed a police report; however, there was no police investigation of the case or action against the abuser.

Without Parental Protection, Children Face Greater Risks

Many children in this study were separated from their parents in their home country as one or both parents either left for the United States or were killed. Out of 183 children, 130 reported some form of parental separation or death; in the remaining evaluations, that data was not collected. Out of the 130 children reporting separation, 63 percent reported that at least one parent was in the United States (usually the primary caretaker), 36.9 percent reported that both parents were in the United States, and 16 percent reported that their parents had died, usually killed by gangs.[42] Results of parental separation included an increased susceptibility to further trauma, neglect, and the burden of becoming a caregiver for younger siblings and family members.

While parental separation can itself be traumatic, the resulting lack of parental protection left children vulnerable to further trauma perpetrated by extended family members or others in the local community. For example, one victim of repeated sexual abuse pleaded with the perpetrator, her cousin, and asked why she was being targeted; the cousin replied, “Because there is no one here to protect you.” Another girl had been left under the care of her grandfather, but he passed away when she was 13, whereupon other family members repeatedly sold her as a prostitute.

One victim of repeated sexual abuse pleaded with the perpetrator, her cousin, and asked why she was being targeted; the cousin replied, “Because there is no one here to protect you.”

Parental absence left children at risk for neglect. One child described his experience being shuttled between distant family members: “Over the next three years, they did not have stable shelter, sometimes slept on the streets, went hungry, did not regularly attend school, and faced the abuse by family members, strangers, and gang members. He reports feeling ‘alone in the world’ though also felt responsible for his younger brother.” In addition to the lack of parental protection, these children were targeted due to the remittances sent by the absent parent. One girl said that she “did not feel safe and felt there was no one to protect her. The only thing she felt she could do to escape abuse was to go to another family member’s house, but then often the abuse continued.… ‘no one loved me’, she stated, ‘They didn’t care about me, they just wanted the money my mom sent them for me.’”

Smugglers Harm Children in Transit

Though the focus of the evaluations was pre-migration trauma related to the asylum application, numerous children assessed in this study described traumatic experiences while in transit to the United States. Many of the vulnerabilities of the children in their home countries were exacerbated during the journey.

Children report being abused, threatened, and assaulted by smugglers or other migrants during their journey. One girl described her travel alone toward the United States and detailed how a trafficker sexually assaulted, kidnapped, and threatened to murder and dismember her: “One of the coyotes who had a gun, began to touch her breasts and genitalia, and no one did anything, although others noticed. ‘You’re mine now. No one is going to help you,’ the coyote said to her.”

One boy was only seven years old when he traveled from Guatemala to Mexico. In Mexico, the smugglers separated him from his mother and told him to hide in a sewer. He was chased by police officers, with dogs, who threw a kind of gas that made him cough and vomit. “He wasn’t expecting this ordeal and wanted to go home. Later he was taken to a house where he cried for his mother, fearing that she’d been detained. He was in several houses over the course of one month and he reports being abused – his head was shaved; he was hit on his back when he cried.” An 11-year-old girl fleeing sexual harassment and domestic abuse travelled to Mexico with a group of children. The group stayed at a housing facility for people waiting to cross the border, which was a large, filthy room with rats, spiders, and piles of garbage. When she refused to engage in sexual relations with “El Gordo,” one of the people in charge of the housing facility, he punished her by making her sleep near the garbage.

In addition to facing cruel treatment from those they met on the journey, the children described the surrounding terrain and overall conditions of the voyage as harsh and extremely dangerous. A boy fleeing gang extortion and forced conscription described traveling through the desert to cross the border. “There was a time when he was lost for three days without food or water. He feared that he would die of dehydration or from an animal attack.” One girl described a frightening and unsafe river crossing: “The person helping her to the United States was taunting her and the other children when they got to the river. She reported that he was discussing the consequences of falling into the river, including certain death. She stated that the group used a tire and rope (which had been tied to a tree) to cross the river.”

U.S. Border Enforcement and Immigration Detention Traumatize Children

Children continued to recount negative experiences at the hands of U.S. government officials upon arrival in the United States. A girl reported that dogs and immigration officers chased her through a field and that one of the dogs tried to bite her. The officer handcuffed her and put her in a car. Another child felt he would be protected if he could only get to the United States. He explained that when he crossed the border and was apprehended by U.S. agents, he shouted out, “I am fifteen,” because he knew that 15-year-olds are entitled to rights as a minor. He described those few minutes as “the scariest moment of [his] life.”

Children also described U.S. detention centers as intimidating, scary, and inadequate. One girl reported that another person in detention had groped her. The officer took her statement and reviewed video footage, but questioned her account, saying that he could not see the event on the video. She asked, “What would I gain from lying about this?” However, the detention facility staff returned her to the same detention area in which she had been groped. One boy recounted that, after being handcuffed, he and his cousin were taken to a facility and interrogated. Because he was a minor, he was separated from his older cousin and taken to a children’s residence. He later found out that his cousin had been deported. He described the fear caused by the lack of information about the immigration process and whereabouts of his family members: “When I was there, I was scared and I didn’t know what was going to happen. I didn’t know what had happened to my cousin.” Another boy spoke of his experiences in La Hielera (‘the icebox,’ a term used to describe U.S. Customs and Border Protection holding cells). He suffered hunger because he was only occasionally given cookies and juice to eat. He remembered that his first day at La Hielera was also his birthday. A clinician observed in an interview with a girl, “She was stoic throughout the interview when describing her torture, and only became tearful when describing being detained in a cold cell on the U.S. side of the border.”

Physical and Psychological Manifestations of Trauma

“The rape is still with me…. I am no longer the same as all the other girls my age…. I’m different. This has changed me forever.”

18-year-old girl from El Salvador

The impact of this complex trauma often resulted in serious effects on these children’s health. The surveyed group presented many medical problems, including acute musculoskeletal and dermatologic trauma, such as bruising, cuts, bleeding, and both acute and chronic pain. Sexual assault survivors often reported pain, bleeding, and, in several instances, unwanted pregnancies. Physical injuries resulting in scars were documented in numerous cases from lacerations, burns, gunshot wounds, and other acute trauma injuries. Head injuries resulting in concussions and potential neurocognitive effects were also suspected in some evaluations. However, the most significant burden of illness in this population was the psychological sequelae of trauma and abuse.

In our sample, 76 percent of children were suspected or diagnosed to have at least one major mental health diagnosis, most commonly post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)(64 percent), major depressive disorder (40 percent), and anxiety disorder (19 percent). The affected children exhibited a broad range of symptoms, from dissociative reactions to symptoms of flashbacks, nightmares, sad and depressed mood, hopelessness, guilt, anger, irritability, and many others commonly associated with these conditions.

76 percent of children were suspected or diagnosed to have at least one major mental health diagnosis.

A nine-year-old boy continues to have PTSD symptoms, such as intrusive thoughts about his abusive father, waking several times per night in fear. He feels safe in the United States but fears that his mother will be killed if they return to Honduras. The clinician noted that his symptoms, along with his young age, may make it difficult for him to consistently narrate his experiences clearly and coherently, especially in high pressure settings such as an asylum interview or an immigration court hearing. A clinician evaluating a seven-year-old boy noted that he laughed and then refused to speak during the evaluation; these are normal reactions to cope with the stress of recounting abuse but could negatively impact credibility in asylum proceedings. Said the clinician, “I had brought a variety of dolls and action figures to the interview. He chose a very big action figure and a smaller doll and had the action figure hit the doll hard several times. When he used the action figure and doll to demonstrate how his father used to repeatedly hit his mother, he began to laugh. In part, this was due to the developmentally normal pleasure in play. It was fun to have dolls at his disposal. However, it is my clinical judgment that the laughter was primarily generated as a defense against keen anxiety. After enacting the father’s attack on the mother through the dolls – an attack in which the attacker was strikingly larger than the victim – he appeared exhausted, stating, ‘I’m done.’”

Even after children arrived in the United States and were placed in stable environments, the lasting impact of trauma was evident in their ongoing difficulties with emotional regulation, social interactions, and bonding with parents and other caretakers. Children often spoke of continued distress, and family members or evaluators frequently described abnormal development and relationships. One evaluator wrote, “He has difficulty connecting to his parents, is extremely quiet, and only speaks when spoken to.” The same child was also described as having verbally and physically violent outbursts, and “has expressed suicidal thoughts and emotional numbing.” He is further described as having “a lack of psychological fluency, impoverished personal narrative, and apparent difficulty working with perceived authority figures.” These children also often described difficulty forming healthy relationships and an inability to trust others because of their experiences.

One boy stated that he “does not feel as though he can trust anyone at his school or community.” Additionally, children faced frequent reminders and triggers of their past trauma. An evaluator described the reactions of a young woman she interviewed, detailing her current experiences in the United States: “When she sees a group of men, which will trigger memories of what happened to her … she feels a 9/10 [degree of fear]…. In these moments she does not know what to do and feels confused and frozen. She avoids activities such as shopping if there is a chance she will see men there. She feels afraid if she hears men yelling. She thought that the ‘white’ immigration officers would assault just like they did in Honduras. She can’t trust people and feels on edge; once a male friend tried to give her a hug but she felt frightened.” The client herself described how she does not “want to get married because [she] feel[s] disgusting.” Trauma expertise is essential to support children to tell their persecution story. One clinician stated, “X was helped with gentle breathing and grounding techniques to help her compose herself. Given her dysregulation and concern of re-traumatization, the self-soothing techniques helped her regain emotional regulation [while narrating the sexual abuse she survived].”

In some of the most alarming examples, young children and adolescents reported emotional distress from both past and recent suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Some of these experiences occurred during past periods of trauma and abuse in their country of origin. For example, a child described her suicidal feelings after years of abuse by her aunt. The years had taken quite a toll on her, until she finally “attempted to kill herself by cutting her wrists with a razor blade. She recalls ‘not knowing what else to do.’ When her aunt saw what she was doing, she grabbed her cut wrist and said, ‘If you really want to die, you have to do it deeper,’ and dug her long fingernail into one of the cuts.” In other cases, the psychiatric illness and suicidal ideation are present at the time of evaluation. One eight-year-old child’s mother reported, “He loses his temper every day, throws things at the wall, smacks himself, and is not aware of what he is doing.” This type of irritability is common in children who have experienced trauma and is considered a symptom of depression. The clinician noticed that his facial expressions were either sad or flat and expressionless; even when saying,“Playing makes me happy,” his facial expression did not match the statement. His mother told the clinician that when her son is in a bad mood, he says he would rather die.

Children Demonstrate Resilience

Despite the extreme trauma these children have experienced, and their resulting developmental, psychological, and physical harm, many reported successfully rebuilding their lives in the United States, where they are safe and secure from physical harm. An adolescent explained his transition, stating “Whatever happened in my country can stay in my country – now that I’m here, it’s like a different world; I don’t want to remember the other world anymore.” Another boy describes being free to live without hiding his sexual orientation: “I didn’t plan to come here, it just happened [because] the situation was getting worse, especially for gay people. They don’t have the freedom to go out, have parties, or have relationships. They are criticized, and they can be killed. Here I don’t hide who I am.” Another young boy, who is an evangelical Christian and comes from an indigenous group, reported that in his country he hid his ethnic and religious identity even from his friends; he was particularly afraid that his traditional dancing would cause him to be a target of violence, as it did not fit dominant cultural views of masculinity. In the United States, he has joined a dance group in his church where he is able to wear his traditional costumes and dance to indigenous folk music.

Many of the children whose cases were analyzed for this study demonstrated resilience and significant physical and psychological improvement since coming to the United States. One boy explained the change, describing how “ever since coming to the United States [he] feels happier. [He] states that he no longer feels scared, can sleep through the night, concentrates well at school, and gets along well with his family. [He] states that he has made many friends at school and has a few friends that live near him and will sometimes meet them to play soccer in the park.” A girl described her life in the United States: “I walk, work, get fresh air, listen to music, try to have conversations with other people. I guess I can see the beauty of the world.” Another boy has scars and joint pain from the blunt force trauma he sustained during beatings, during which he also sustained significant head injuries resulting in concussion and post-concussive syndrome (loss of consciousness, vomiting, months of headaches). Due to years of abuse by gangs, he made two suicide attempts in his home country. The clinician concluded, “Although his current symptom burden is much less, it is significant that this drastic improvement seems largely facilitated by finding relief from his violent circumstances and safety in the United States”

Another crucial component of these children’s recovery is the ability to envision a better and more hopeful future and to make a contribution as a valuable member of society, including through turning their negative experiences into a way to help others. One child described how “she feels safe in the United States. She hopes to attend university to become a psychologist. She wants to feel better herself and then help others overcome fears and trauma, especially sexual trauma.” Another explained his goals, describing how “when he is older he wants to be a lawyer so he can protect and defend his family. He also wants to be in the military in the United States to defend the United States and his family from danger. He wants to stay in the United States so he can reach his goals.” One “likes the idea of being a police officer so he can help people;” another “wants to study criminal justice. He says he is very interested in justice. When asked why, he states that he ‘wants to help provide justice to people who don’t have it, including those of [his] country.’”

Legal Framework

Human Rights Law Standards

Since 89 percent of the children in the data set come from countries in the Northern Triangle – El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras – and transit through Mexico to seek asylum in the United States, the legal framework reviews relevant provisions governing the protection of children from the forms of violence mentioned in the study, both in Inter-American regional standards and national laws in the children’s respective home countries. When states persecute or fail to prevent persecution on the basis of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership to a particular social group, international law provides asylum as a solution to meet those protection needs. Since the study’s findings indicate a failure of state protection according to these standards, we then review the legal basis for possible asylum claims in the United States as well as international and U.S. legal and policy standards governing the treatment of child asylum seekers.

Protections under International and Regional Law

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights guarantees rights to all individuals within a state party’s jurisdiction, regardless of national or social origin, without discrimination.[43] These rights include the right to life, the prohibition of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, prohibition of arbitrary detention, and humane treatment for detainees.[44] Protection of the family unit by the state is also a recognized civil and political right.[45] Finally, children’s right to special protection, regardless of national or social origin, is also recognized as a civil and political right.[46]

The American Convention on Human Rights explicitly establishes the rights of children. For example, article 19 states, “Every minor has the right to the measures of protection required by his condition as a minor on the part of his family, society, and the state.”[47] The American Convention does not permit suspension of any rights pertaining to children or the family; the Convention is different from all other human rights instruments in this aspect.[48] The Inter-American system integrates regional documents and court decisions with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and decisions of the corresponding committee to establish the rights of children.[49]

In this respect, the Inter-American system recognizes principles such as the best interests of the child, as established in the CRC.[50] Numerous advisory opinions and court decisions of the American system have confirmed the validity of child rights standards in practice,[51] including protections for street children,[52] protection of children from police brutality,[53] reparations for denial of education for children,[54] and accountability for detention conditions.[55]

Specific protection against gender-based violence, including domestic violence, is also addressed at the regional level. The Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women, known as the Convention of Belém de Pará, calls for the protection of women and girls from physical, sexual, and psychological violence.[56] The Convention specifies that women should be free from violence perpetrated by assailants who are known or unknown, including when occurring in domestic or interpersonal relationships.[57] The Convention has been ratified by 27 states and acceded to by another five states, evincing recognition in the region of state obligation to protect women and girls from violence.[58]

Protection under National Laws

The Northern Triangle countries – El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras – and Mexico have laws in place to protect children, but enforcement remains a challenge. El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras have criminalized child abuse, but it remains a serious problem in all three countries as well as in Mexico,[59] with an extremely high rate of impunity for crimes against children in Guatemala.[60] Domestic violence is against the law in El Salvador and Honduras,[61] however, domestic violence laws are poorly enforced in El Salvador, and punishments for domestic violence vary widely in Honduras.[62] In Mexico, spousal abuse is not criminalized under federal law, and state laws on domestic violence are often unenforced.[63] Guatemala, El Salvador, and Mexico have enacted statutory rape laws,[64] but Honduras does not even have a law criminalizing statutory rape.[65] Reports indicate that the sexual exploitation of minors remains a problem in El Salvador, Honduras, and in the border regions of Mexico.[66] The U.S. State Department reported that rape laws were ineffectively enforced in both El Salvador and Guatemala in 2018.[67]

Responses to gang violence in the region mostly take the form of punitive security policies with names like “Iron Fist” and “Zero Tolerance”, which rely on mass arrest, incarceration, and militarized policing, with reports of police brutality and extrajudicial killings.[68] Alternative approaches such as safe school initiatives, specialized services, and violence prevention measures are positive, but chronically underfunded and limited in capacity.[69] High-level initiatives to end corruption and impunity for violence, such as the UN’s Commission against Impunity in Guatemala, though widely popular, face political opposition and an uncertain future.[70]

In spite of the existence of regional and national laws which should protect children, these laws are not adequately enforced, which may amount to failure of state obligation to protect children.

International Law Requires a Due Diligence Standard

Adequate legal framework is important, but not sufficient for the protection of children. Even when violence or persecution is not committed directly by state actors, international law and jurisprudence makes clear that states are responsible for exercising due diligence to protect all people in their jurisdiction from attacks by non-state actors. Remedies must be accessible and effective in order to fulfill state obligations.[71] The due diligence standard requires that states effectively investigate, prosecute, and punish perpetrators, as well as provide effective protection mechanisms; failure to do so represents an abrogation of states’ legal obligations.[72] In addition to state failure to investigate, which results in de facto impunity and encourages future violations, failure of the state to provide specialized services for children who are abandoned, neglected, or exploited can amount to a violation, because it exposes them to increased risk.[73]

More comprehensive approaches not only define the elements of a crime, such as domestic violence,[74] but also establish proactive measures to prevent and protect from violence, including creating specialized police officers to assist female victims[75] and promoting public education on gender equality and the rights of women.[76] Laws can designate appropriate methods of assistance for courts, health care workers, and police officers.[77]

Protections under Asylum and Refugee Law

U.S. and international refugee law provide a legal solution – asylum – for instances where severe harm on a discriminatory basis is combined with failure of state protection. When states fail to protect the basic rights of those within their jurisdiction, mechanisms for international protection are triggered. The principle of non-refoulement, which exists under international refugee law[78] and as customary international law,[79] prevents states from returning a person to any country where their life or freedom would be threatened on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.[80] A state is also prevented from returning a person to a third state where there is a risk of further return to the country where the threat exists to their life or freedom.[81] Non-refoulement also implies an obligation of temporary admittance of asylum seekers at the border in order to assess asylum claims so as to ensure meaningful review and prevent returning individuals to serious harm.[82] Non-citizens who are lawfully present in the state’s territory are entitled to procedural protections before removal, including the opportunity to appeal the decision of removal.[83] The United Nations General Assembly has affirmed the principle of access to a fair and efficient refugee status determination process.[84]

The Cartagena Declaration on Refugees expands the definition of ‘refugee’ to any person fleeing persecution on one of the five protected grounds in the Geneva Convention, or based on threats to safety or freedom by “generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights, or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order.”[85] The adoption of this definition by 14 countries, including the Northern Triangle countries and Mexico,[86] indicates emerging local consensus that regional trends in forced displacement support a wider definition for application of refugee protections.

Asylum Protection from Persecution from Gang Violence

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees Handbook on Refugee Status Determination states that acts committed by non-state actors can be considered persecution if the authorities knowingly tolerate the acts, or if the authorities refuse or are unable to offer effective protection.[87] Asylum jurisprudence, in the United States and internationally, confirms that discriminatory attacks by non-state actors such as gang members can qualify as persecution for the purpose of asylum claims.[88] U.S. law recognizes persecution by non-state actors, as long as the asylum seeker is able to prove that the government is “unable or unwilling” to control the persecutors.[89] High rates of impunity, police and government corruption, and failure of police to either investigate reported crimes or offer protection indicate government inability or unwillingness to control non-state actors who are harming children. Relevant factors to understand the basis for gang violence survivors’ asylum claims include past resistance to gang activity, former or current gang membership, and whether they are victims or critics of the state’s anti-gang policies and activities.[90] When assessing the presence or absence of state protection, a lack of effective witness protection and public perception of seeking police help as futile or actually increasing the risk of harm are important factors to consider.[91] Generally, gang-related claims have been assessed under political opinion or membership in a particular social group.[92] For children targeted or recruited by gangs, courts have recognized that their age, in other words, their identity as “children,” may also be considered as a protected particular social group which may fall under criteria for asylum.[93]

Asylum Protection from Persecution Involving Domestic Violence

International human rights law makes clear that severe forms of domestic violence, in the absence of state protection of victims, can amount to violations of the right to freedom from torture and inhumane treatment.[94] Asylum jurisprudence, in the United States and internationally, confirms that, for the purpose of asylum claims, discriminatory attacks by family members or intimate partners can qualify as persecution when government authorities do not provide effective protection.[95] UN High Commissioner for Refugees’ interpretive guidance advises that domestic violence survivors may be considered members of a particular social group with gender as an immutable characteristic, or gender combined with relationship status, national origin, or other characteristics.[96] A recent U.S. court ruling has reaffirmed the right of domestic violence survivors to pursue asylum claims based on credible fear of persecution as members of a particular social group.[97] U.S. courts have also recognized domestic violence as a form of persecution, which triggers the application of asylum protections, specifically in the case of abused children.[98]

Asylum Protections for Children

Children are uniquely vulnerable to child-specific forms of persecution, such as under-age recruitment, child trafficking, female genital mutilation, underage marriage, child labor, child prostitution, and child pornography.[99] Children are also likely to be more affected by harms to family members, especially parents, due to their dependency. However, states cannot expect children to participate in immigration systems and asylum proceedings in the same way that adults can.

Children may need accommodations or assistance in order to tell the story of their persecution, which takes into account their trauma, level of development or education, submission to authority figures, and lack of understanding of events in their home country and of asylum procedures.[100] In recognition of the particular vulnerability of children, U.S., regional, and international law provide additional protections for child asylum seekers above the standard of asylum protections for adults.

The CRC requires state parties to consider the best interests of the child in all actions.[101] The Convention mandates that a minor seeking asylum be afforded “appropriate protection and humanitarian assistance in the enjoyment of applicable rights.”[102] Experts also advise that the child’s best interests be seriously considered as an independent source of international protection during child asylum and removal decisions.[103]

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights has applied the principle of non-refoulement to children, even when the child has not yet received refugee status but has asserted their intent to apply for asylum, including at the border.[104] The Court stated that the decision on the return of a child to their country of origin or to a third country should always be based on the best interests of the child.[105] According to the Court, states must protect the need of children to grow and develop, and must accordingly offer “the necessary conditions to live and develop their aptitudes taking advantage of their full potential.”[106] Furthermore, states should account for “the specific forms that child persecution may adopt, such as recruitment, trafficking, and female genital mutilation” when adjudicating asylum claims.[107] The procedures for seeking asylum, including permitting asylum-seekers to enter the country at the border, must be executed irrespective of whether or not a child is accompanied by a parent or adult relative.[108]

Regarding child detention, the CRC forbids unlawful or arbitrary imprisonment, and states that “[t]he arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child shall be … used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.”[109] Moreover, the Convention states that “[e]very child deprived of liberty shall be treated with humanity and respect for the inherent dignity of the human person, and in a manner that takes into account the needs of a person of his or her age.”[110] Although the United States has not ratified the CRC, and is the only country in the world not to have done so, as a signatory to the treaty, the United States is bound by customary law not to violate the object and purpose of the treaty.

Family unity is a fundamental tenet of refugee law, recognized as an essential right which obliges governments to protect families.[111] The Inter-American Court of Human Rights stressed the importance of the family unit in the context of migration and noted that a child “has the right to life with his or her family.”[112] The concept of family unity was recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court as a fundamental right protected by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution: “The interest of parents in the care, custody, and control of their children.”[113] The right includes the ability to make decisions regarding the upbringing of children, to establish a home, and to control the child’s education.[114] U.S. government actions to separate parents and children in the context of immigration law enforcement in 2018 were halted with an injunction, and the government was required to reunite the separated parents and children, demonstrating the continuing importance of family unity as a guiding norm.[115]

U.S. Laws and Policies Recognize Child Asylum Rights