Executive Summary

In the early morning hours of June 3, 2019, Sudanese security forces launched a violent attack against pro-democracy demonstrators at the protests’ central sit-in site in Khartoum, near the headquarters of the army, navy, and air force – a neighborhood known in Khartoum as “al-Qiyada,” or headquarters. Reports in the aftermath of that attack indicated that the violence resulted in the deaths of scores of people and injured hundreds more.[11] Witnesses and survivors of the violence – referred to as the June 3 massacre – reported that various uniformed elements of Sudan’s security forces were responsible for extrajudicial killings and forms of torture, including excessive use of force; cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment; and sexual and gender-based violence.[12] In addition, there have been allegations that the security forces forcibly disappeared[13] dozens of protesters detained on or around June 3.[14]

This extraordinary political moment in Sudan was a crucial turning point in the revolution which had started on December 18, 2018, when civilians began protesting for an end to 30 years of dictatorship. The National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS), along with other security forces, had attacked multiple protest sites, causing deaths and injuries. On April 6, 2019, civilians protested at al-Qiyada, and responded to attacks by security forces who used tear gas and crowd-control weapons by creating a public sit-in camp there. Following violent attacks on civilians from April 6 to 10, President Omar al-Bashir stepped down on April 11. The protesters remained at the sit-in to demand civilian rule. Security forces attacked protesters on multiple occasions in early and late May, but the civilian communities that had formed within the sit-in persevered. After April 11, many civilian groups raised tents and chose to live communally within the sit-in area. Participants recalled that the evenings in the sit-in area were full of social and political activities, and that this experience led to a powerful shared vision of a civilian-led Sudan in which freedom, peace, and justice would be available for all.

The June 3 violence against protestors – including the massacre by security forces – shocked participants and observers with its disproportionate ferocity and scale; those violations are the focus of this report. But instead of retreating from further protest in the face of unknown numbers of deaths and injuries, Sudanese citizens persisted in demanding civilian governance. The protests helped sustain negotiations between the Forces of Freedom and Change and the Transitional Military Council, which culminated in the signing of a new Constitution and the formation of a civil-military transitional government on August 17, 2019.

Witnesses and survivors … reported that uniformed elements of Sudan’s security forces were responsible for extrajudicial killings and forms of torture, including excessive use of force; cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment; and sexual and gender-based violence.

Physicians for Human Rights’ (PHR) investigation into the violations that occurred on June 3 focused on: the nature of the injuries and other physical trauma resulting from events on June 3, 2019 in Sudan; patterns in the testimonies of interviewees and medical evidence to assess allegations of a systematic, widespread, and premeditated campaign of human rights violations by Sudanese security forces; and to what extent, if at all, security forces targeted health workers for detention and ill-treatment due to their emergency medical response and other efforts to support the provision of medical care for injured pro-democracy protesters. These issues are central to the discussion among citizens, democratic forces, and human rights defenders in Sudan, where the new transitional government has formed a national commission to investigate the violence. Victims’ families and survivors of these and other serious violations await truth and accountability.

For this report, a PHR clinician-investigator conducted semi-structured interviews and brief structured clinical evaluations based on the Istanbul Protocol[15] in Khartoum between August 23 and November 9, 2019 with 30 survivors and witnesses to the June 3 violence, of whom four were women and 26 were men. These included 21 pro-democracy protesters, and health workers working in a wide range of health sectors: four physicians, one pharmacist trained as a medic, one medical coordinator, one volunteer, and one psychologist.

In many cases, perpetrators identified themselves to their victims as belonging to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a then-paramilitary group now incorporated into the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF).[16] This report documents the nature of the injuries resulting from events on June 3, as well as patterns in the testimony and medical evidence that support allegations of a systematic, widespread attack. While more data may be necessary to generalize knowledge about the intentionality and purpose of the attack, this investigation contributes to the public record of violence carried out against civilians on June 3.

This report indicates that Sudanese authorities had in the days prior to the June 3 violence purposefully pre-positioned large numbers of security forces in and around the sit-in site, particularly in late May, in what appeared to be part of coordinated pre-attack planning. Interviewees who participated in the sit-in from April 6 through the end of May noted that security forces who had interacted peacefully with protesters were withdrawn in the weeks prior to the June 3 attack and replaced with forces that were openly hostile to protesters, including many with accents and features identified as belonging to the Rizeigat tribe from the Sudanese region of Darfur, long known for its participation in the Janjaweed militia, which in 2013 was formed into the RSF. Those forces were armed with weapons including tear gas, whips, batons, sticks, pieces of pipe, and firearms, including Kalashnikov assault rifles.

That hostility and weaponry was deployed in the violence that security forces unleashed on the sit-in participants on June 3 in the form of extrajudicial killings and excessive use of force. Interviewees described how they witnessed security forces shoot unarmed protesters in the head, chest, and stomach from a distance. Large groups of armed men in RSF and riot police uniforms surrounded and beat people with batons, whips, and the butts of their rifles. Interviewees recounted how security forces taunted them while beating, burning, and cutting them. The brutality described by interviewees was supported by PHR’s clinical evaluations of wounds of survivors of the violence. Survivors and witnesses described how security forces continued to victimize pro-democracy demonstrators that they detained through torture and other deliberately degrading treatment, including forcing detainees observing the daylight fasting of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan to drink from puddles of dirty water on the street.

Sexual and gender-based violence was also a key component of the abuse that security forces inflicted on pro-democracy demonstrators. Interviewees described how forces grabbed the genitals of both male and female protesters and threatened to take off women’s pants. A witness described an attempt by armed men to sexually assault him after they detained and tortured him, cutting open a healed wound and putting out cigarettes in it. Several interviewees reported witnessing gang rapes of women in open-air settings. Another described encountering rape survivors while being held in a women’s jail.

The June 3 assault continued a pattern of attacks by Sudanese security forces on health care providers, institutions, and patients, as well as the blocking of access to care at surrounding hospitals. Relevant RSF violations against health workers and health infrastructure included the imposition of siege-like conditions on health facilities, restricting ambulances and other vehicles from transporting injured protesters to health care facilities, and beating or shooting health care workers, patients, or visitors who tried to enter or leave health care facilities on foot.

On August 17, 2019, Sudan established a transitional civil-military government and adopted a new constitution containing explicit commitments to promote human rights and access to justice. Article 7(16) of the Constitutional Declaration created a commission tasked with conducting a “transparent, meticulous investigation” of the violations that were committed on June 3, 2019 but did not provide a clear accountability mechanism. In addition, the Constitutional Declaration did not abrogate or otherwise modify laws that prevent access to justice for survivors and families of the dead, instead incorporating existing laws governing security forces that provide immunity for acts committed in the line of duty.[17] PHR welcomes official reports that victims and family members of the dead will be provided access to justice through the legal system,[18] yet it remains concerned with the well-documented flaws in Sudanese criminal and immunity-from-prosecution laws that remain unchanged by the adoption of the new constitution.[19] The leader of the RSF, General Mohamed “Hemedti” Hamdan Dagalo, serves as the vice president of the governing Sovereign Council. Advocates in Sudan may therefore find it difficult to prosecute cases against members of the armed forces, including the RSF, at the highest levels of command responsibility.[20]

PHR urges all Sudanese organizations – as well as international organizations and governments with an interest in promoting peace and democracy by rejecting impunity in Sudan – to support the pursuit of justice and accountability for the abuses of June 3, 2019 through impartial and independent investigations. Those same organizations should support the longer-term strengthening of human rights mechanisms in Sudan by providing international technical and financial assistance. PHR supports its Sudanese colleagues in rejecting impunity and pursuing justice and accountability for victims, survivors, and their families in every forum available, including, where necessary, in international courts as provided for in Article 67(g) of the new constitution. Experience has shown that peace and justice are mutually reinforcing, and that without acknowledgement of suffering, justice cannot be achieved.

Key Recommendations

To the Sovereign Council of the Government of Sudan:

- Support fully the national commission established to investigate violations that occurred on June 3; permit the commission to accept support from international entities with a demonstrated record of undertaking or supporting impartial and independent efforts for justice and accountability;

- Hold all perpetrators of rights violations related to the June 3 massacre accountable in fair and transparent legal procedures;

- Adhere to provisions of Sudanese law that affirm basic human rights principles, including Chapter 14 of the Constitutional Declaration of 2019, and ratify the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment;

- Fully investigate the deaths that occurred as a result of the June 3 violence, identify bodies, provide families with adequate reparations, including all available information about the fate of their relatives, and return remains to families for proper burial.

Shot in the Head: Nassir’s Story

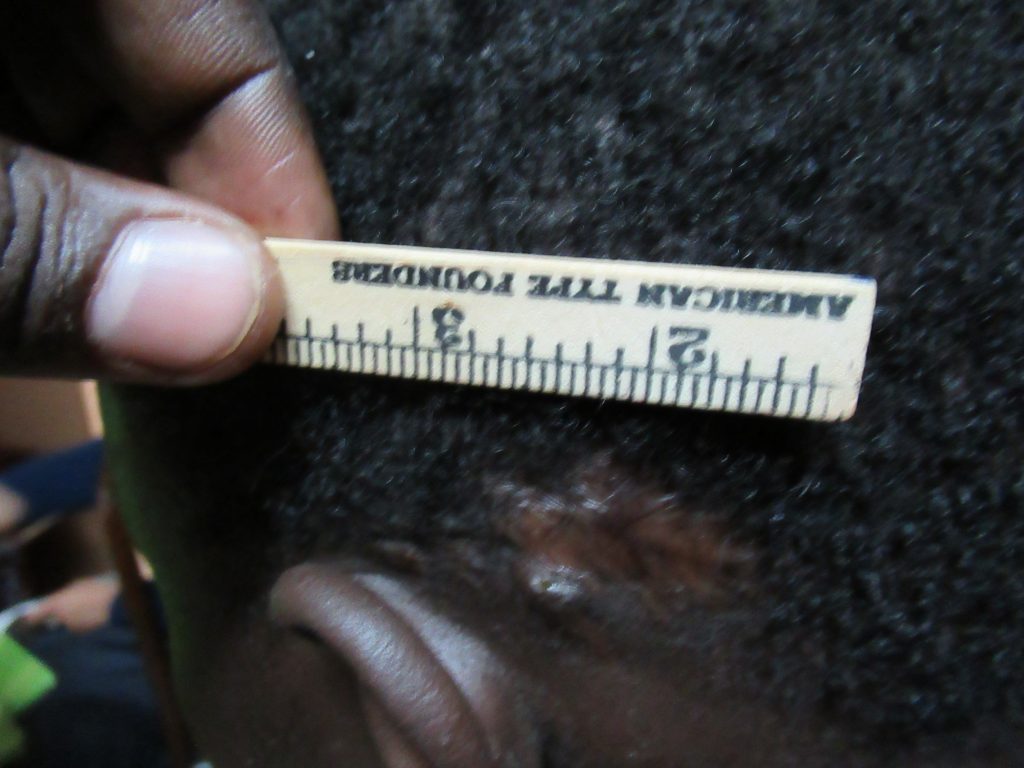

physical examination, which found that Nassir has

difficulties in motor function and speech while retaining

the ability to think and draw, are entirely consistent with a

deep left-sided injury to the parietal lobe of the brain.

PHR’s clinician said that his continued seizures and his

inability to articulate clearly three months after the injury

raise concerns about Nassir’s ability to recover fully

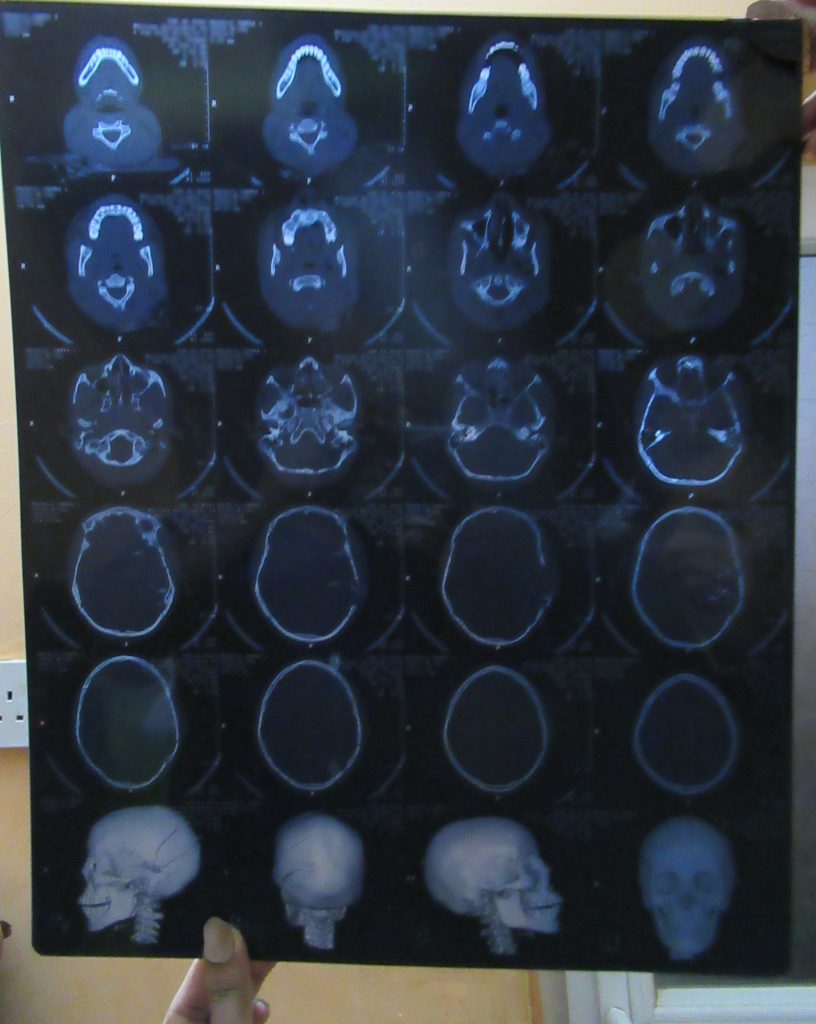

Fifteen-year-old Nassir[21] often attended the protests when he was not working. On the morning of June 3, he was at the sit-in, where he sustained a gunshot wound behind the left ear. Nassir was admitted to Dar el-Elaj Hospital at 6 a.m. on June 3; the medical staff did not expect him to survive. Although it was difficult because of the ongoing violence, the staff located a neurosurgeon to remove the bullet from his brain.

Nassir spent two days in the ICU but, unable to speak because of his brain injury, he remained in the hospital as an anonymous patient for weeks. He showed compulsive behaviors and had to be tied to his bed so that he would not fall out. A group of volunteers working to help the injured from the sit-in put him in contact with a psychotherapist. The therapist, who attended the PHR interview with Nassir and an adult guardian, explained, “He was very scared of us, and he wouldn’t even eat or drink the first few days.”

Although he could not express himself because of the injury, the staff surmised that Nassir had been at the sit-in from drawings he did of the navy headquarters and men wearing Rapid Support Forces (RSF) uniforms with their trademark red hats. Nassir experienced severe episodes of post-traumatic stress and would get scared when anyone came into his hospital room, covering his face to hide from the volunteers. His symptoms improved with antidepressants; however, because he couldn’t communicate, he remained unidentified.

His therapist described how Nassir would become uncomfortable looking out the window. Eventually she realized that Nassir was disturbed by seeing the al-Bashir Medical City construction site, from which witnesses reported seeing snipers on June 3. “He would get uncomfortable and close the curtains. He started drawing the sit-in, the pick-up trucks and officers and blood…. He would draw red hats [the RSF uniform].”

“He couldn’t speak, and we didn’t know his name,” she continued. The volunteers asked Nassir names of areas and he would shake his head or nod until they determined his neighborhood. They made missing person posters and hung them there, with no result. Finally, they recited numbers to him, and he nodded until the volunteers were able to construct a phone number. After multiple attempts, they were able to reach Nassir’s uncle.

According to a clinical consultation carried out by PHR’s investigator, Nassir’s continued seizures and inability to articulate clearly more than three months after the injury raise concerns about his ability to recover fully. For many like Nassir, the extreme violence unleashed upon them on June 3 is highly likely to lead to a lifetime of chronic pain and disability.

* All names in this report are pseudonyms, to protect the participants’ identities.

According to a clinical consultation carried out by PHR’s investigator, Nassir’s continued seizures and inability to articulate clearly more than three months after the injury raise concerns about his ability to recover fully. For many like Nassir, the extreme violence unleashed upon them on June 3 is highly likely to lead to a lifetime of chronic pain and disability.

Introduction

This report focuses on the significant human rights violations against civilians that occurred in Sudan on June 3, 2019 during a large-scale attack by government security forces on the site of a pro-democracy sit-in in central Khartoum. An interdisciplinary team conducted English and Arabic open-source investigation and extensive field-based interviews using established methods, including those informed by medical-legal assessments of injuries. While clear patterns and key events can be established based on the data collected, the data does not permit a forensic reconstruction of the June 3 attacks. Rather, this report demonstrates the need for further in-depth investigations within Sudan by the Sudanese legal and human rights communities, or international bodies such as the United Nations or the African Union.

The report focuses on violations within the sit-in area that occurred on June 3 because of the high number of severe injuries and deaths reported in that location. However, these incidents make up only a portion of the violations that occurred during this period in Sudan. Other serious violations occurred across the country as security forces cracked down brutally on demonstrations in Kordofan, Darfur, and Blue Nile States.

At the time of writing, the political situation in Sudan is dynamic, yet much opportunity for progress exists. On August 17, 2019, Sudan established a transitional civil-military government and adopted a new constitution containing explicit commitments to promote human rights and access to justice. Unfortunately, the new constitution did not abrogate or otherwise modify laws that currently deny justice for survivors of violations carried out by security forces, and families of those killed by them. Instead, it preserves existing laws, in particular those that provide immunity for acts committed by security forces in the line of duty.[22] The future of Sudan’s new democracy in large part depends on how the transitional government fulfills the promise of the constitution for which so many protesters have suffered and died.

Background to the June 3 Incidents and Massacre

As detailed in PHR’s April 2019 report, “Intimidation and Persecution: Sudan’s Attacks on Peaceful Protesters and Physicians,” Sudanese civilians have mobilized in increasingly large protests since December 18, 2018.[23] These protests were triggered by spiraling inflation and the rising cost of bread and fuel and culminated in mass demonstrations demanding that then-President Omar al-Bashir – who had ruled as Sudan’s dictator for 30 years, and who the International Criminal Court formally charged with genocide in 2010[24] – step down.[25] Between December 2018 and April 11, 2019, government security forces, especially the National Security and Intelligence Service (NISS), responded to the protests with excessive force, detaining many protesters. Doctors’ organizations[26] played an important role in organizing and maintaining the protests, in particular as active members of the Sudanese Professionals Association.[27].

After President al-Bashir’s ouster on April 11, 2019,[28] a Transitional Military Council led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan took power, with General Mohamed “Hemedti” Hamdan Dagalo as his deputy. [29] Hemedti leads the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) which would be widely blamed for the June 3 massacre.[30] Under the Constitutional Charter for the Transitional Period, the RSF has been incorporated into the armed forces.[31] Sudanese and foreign commentators agree that the RSF currently dominates the security establishment in Sudan, eclipsing the power of the other armed forces,[32] and witnesses later interviewed by PHR would report seeing armed men in RSF uniforms kill and injure protesters at the sit-in.

The lead-up to the violence of June 3 was a prolonged, mass pro-democracy sit-in that began on April 6, 2019 and sprawled across much of the University of Khartoum’s central campus, as well as in front of the Sudanese army, navy, and air force and artillery headquarters.[33] The participants at the peaceful sit-in were periodically attacked by security forces, including RSF and NISS, who killed and injured dozens of protesters. A well-publicized shooting on May 13 resulted in the death of five protesters.[34] These attacks mirrored previous patterns of violence against health care workers and peaceful protesters in Sudan.[35] These violations, and the many that have occurred across Sudan since the June 3 massacre, lie outside the ambit of this report. However, numerous publicly available media reports and investigations,[36] including those by independent Sudanese civil society groups and international observers, demonstrate that human rights violations committed against civilians involved in peaceful protests from December 2018 through the present constitute serious crimes and merit full and impartial investigation.[37]

Methodology

Physicians for Human Rights’ (PHR) interdisciplinary team of investigators included legal and regional experts, physicians, forensic experts, and investigative personnel.[38] The Khartoum-based team consisted of a clinician supported by three assistants during the interview process. Investigators employed purposive sampling to recruit interviewees who had witnessed or experienced violence during protests from December 18, 2018 through August 2019. The team collaborated with local organizations, health facilities, and community networks to identify initial interviewees and utilized their networks and contacts to recruit additional participants via a chain sampling methodology. Respondents included individuals who sustained physical injuries, or who directly witnessed violations. Health care workers were specifically sought for their knowledge of protesters’ injuries, in addition to their own injuries.

The PHR clinician-investigator obtained consent from each interviewee following a detailed explanation of PHR’s work, the purpose of the investigation, and the voluntary nature of participation, and an explanation of the potential risks of participation. If they provided consent, survivors participated in a semi-structured interview and physical examination based on the Istanbul Protocol, the United Nations guidelines for the investigation and documentation of torture and ill-treatment. [39] To minimize the risk of participation and to preserve the confidentiality of the participants, PHR has replaced their names with pseudonyms in this report and used pictures taken in an anonymized manner.

PHR’s team determined consistency between survivor narratives and physical findings. Investigators evaluated how each injury was sustained; characteristics of any resulting wound, such as depth, shape, scarring pattern, and time frame of the healing pattern; and any additional scars that resulted from secondary infection or surgical treatment. The clinician-investigator corroborated this information with individual testimony and any additional data or medical records in order to make an assessment of consistency for each individual wound and scar, as well as for the totality of the injuries evaluated. In-depth qualitative analysis was then undertaken to determine legally significant fact patterns.

Interviews were conducted between August and November 2019 in secure, anonymous locations in Sudan. Interview questions focused on violence experienced and injuries sustained, and consequences, such as physical disabilities and ongoing psychological issues. For those with physical injuries and scars, the clinician-investigator conducted detailed physical examinations of scars resulting from gunshot wounds, blunt or penetrating trauma, burns, and any other physical injuries. The clinician-investigator used sketches and photographs to document survivors’ scars, and assessed signs and symptoms of psychiatric distress, including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. These assessments were reviewed by a U.S.-based medical expert. However, given time, privacy, linguistic, and other resource constraints, the team did not conduct full psychiatric evaluations. To maintain participants’ anonymity, investigators coded demographic data, incident descriptions, types of injuries suffered, any ensuing disabilities, descriptions of witnessed abuses, and, when known, perpetrator identities – including the specific force to which they belonged.

Contemporaneous with the field investigation, PHR’s partners at the Human Rights Center Investigations Lab (HRC Lab) at the University of California, Berkeley conducted an open-source investigation of social media posts from Sudan at the time of the protests. [40] Using a multi-source verification process, the HRC Lab researchers verified instances of human rights violations in Sudan in June and July 2019. As discussed below, the HRC Lab found significant open-source evidence that the Rapid Support Forces conducted attacks on two private hospitals on June 3, which corroborated information about these attacks provided in interviews.

PHR obtained a list of 71 mortuary admissions related to the events from June 3, 2019 through June 6, 2019 in Khartoum, Sudan.[41] The data included name (where known), age, and cause of death. The locations of these deaths and the contexts in which they occurred were not provided. The data corroborated reports of extrajudicial killings, as detailed below.

PHR’s Ethics Review Board reviewed and approved this report based on regulations outlined in Title 45 CFR Part 46, which are used by academic institutional review boards in the United States. All PHR’s research and investigations involving human subjects are conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 2000, a statement of ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects, including research on identifiable human material and data.[42]

Terminology

In this report, the term “health worker” refers to individuals who, at the time of attack or detention, were engaged professionally or as volunteers in the search for, or collection, transportation, diagnosis, or treatment of the wounded and sick (including provision of first aid); in the prevention of disease; or in the provision of logistical or administrative support to health services. Health workers can include physicians, nurses, paramedics, ambulance drivers, search and rescue personnel, pharmacists, and others.

Limitations

The sample size and purposive sampling methodology was intended to explore the range of injuries, establishing the geographic, temporal, and legal scope and scale of the abuse, and to gather physical evidence of reported human rights violations. This report was not designed to provide prevalence of specific types of injuries, or of exposure to violence. To our knowledge, there are no reliable estimates of how many people were injured during these events, and death estimates vary. Our analysis of the mortuary admissions report was limited by a lack of contextual detail and the unavailability of information about the number of deaths in months in which no violence allegedly took place.

A number of practical constraints may have affected the findings. We attempted to interview an equal number of women and men; however, PHR was able to interview only four female respondents with relevant experience. Although some observers estimate that the gender composition of participants at the sit-in was roughly equal,[43] the chain sampling may have led to introductions to more men than women. The team did not interview anyone who directly experienced sexual violence. This may have been be due to security concerns, religious taboos in this conservative predominantly Muslim country, cultural constraints, and stigma attached to sexual violence. As a result, both male and female rape survivors may be underrepresented in this group. While investigators asked about psychological symptoms, formal psychological assessments were not performed. Finally, we focused our interviews on incidents that occurred only on June 3, potentially limiting our knowledge of other human rights violations that may have occurred on other dates.

Note on Internet Suppression

The lack of internet in Sudan beginning June 3 may have limited the availability of open-source material related to the June 3 massacre and later violence. The Transitional Military Council (TMC) governing Sudan suspended the internet during the day of June 3, making visual documentation of the June 3 massacre and the violence that continued afterwards more difficult to obtain. Although witnesses described many videos and photos of attacks on health care that were taken on June 3, many of these were not posted, or were taken down. Protesters filming or taking photos reported they were targeted for violence.[44] Tamador, a protester at the sit-in on June 3, described urging witnesses inside Moallem Hospital, where many of the injured were first taken, not to film the forces outside, because she was afraid this would provoke a more violent attack. Access to social media was limited due to government suppression of mobile networks beginning June 3,[45] with increasing restrictions[46] leading to what the UN independent expert on Sudan described as a “countrywide shutdown” of the internet by the TMC from June 10 to July 9.[47] Zain, the largest internet provider in Sudan, restored service only in response to a Khartoum district court order.

Findings

Of the 83 survivors invited to participate in the report between August and October 2019, 37 accepted: five women and 32 men. The most frequent reason for declining participation was lack of time, followed by fear of persecution and lack of trust. This analysis focuses on the reports of 30 of these survivors – four women and 26 men – who experienced or witnessed human rights violations on June 3, 2019.[48]

Table 1: Demographic Summary of Participants

| Age Group | 11-17 | 18-29 | 30-45 | All |

| Number of Survivors | 1 | 17 | 12 | 30 |

| Number of Males | 1 | 16 | 9 | 26 |

| Number of Survivors Injured on June 3 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 15 |

Countdown to a Massacre

The June 3 attacks occurred on the last day of Ramadan, prior to a three-day celebration known as Eid al-Fitr that marks the culmination of the month of ritual fasting. While there is no consensus on the exact number of demonstrators at the sit-in site, there is agreement among interviewees that numbers had declined as the holiday approached. A focal point of the sit-in and the subsequent violence on June 3 was an area adjacent to the University of Khartoum campus to the north near the Blue Nile Bridge, known, according to interviewees, widely but informally as “Colombia.” The area gained that name because of the widespread illicit trade in marijuana, alcohol, and other drugs that occurred there.[49] Lower-ranking officers in the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) allegedly permitted and at times consumed the illegal drugs.[50] The Transitional Military Council (TMC) would later state publicly that the attacks of June 3 were prompted by complaints about the need to “clean up” the drug dealing and other activities taking place in the area locally referred to as “Colombia.”[51] PHR’s interviews indicate this explanation is not credible, since people living in that area had already been dispersed violently by security forces, including Rapid Support Forces (RSF) personnel, between May 29 and June 2. These attacks appear to have facilitated the placement in strategic areas of RSF transport vehicles, open-bed land cruisers commonly referred to in Sudan as “Thatchers.”[52]

Meanwhile, sit-in participants had undertaken extensive preparations in anticipation of public prayers and communal feasting, and a chef had been brought in by organizers to make traditional food at an on-site kitchen. Many protesters slept on-site in large community tents organized by town, profession, neighborhood, or professional group affiliation. Groups from Darfur and distant towns camped at the sit-in, congregating in the large tents and preparing to celebrate the holiday.[53]

Eyewitness accounts provide insight into the lead-up to the violence against pro-democracy demonstrators on June 3 as well as the size and composition of the security forces implicated in that violence. Interviewees told PHR that during the preceding months of pro-democracy protests in Khartoum, protesters and RSF soldiers interacted positively. Dr. Amina, a witness to the June 3 violence who is a therapist and professor, spent significant amounts of time at the sit-in from its beginning on April 6. She recounted spending most evenings there, returning home often at 3 a.m. She described how the RSF soldiers “used to even eat with protesters…. I remember one time they were sleeping, and protesters were guarding [their posts] for them…. They used to pray with them and everything.”[54] Witnesses reported a shift in the composition of the troops in the weeks before the massacre. Interviewees thought that this reflected a plan to remove soldiers from the sit-in post who might have developed an affinity for the protesters, and which could reduce the likelihood that the soldiers would protect protesters from attack, as they had in the past. Interviewees indicated that during the weeks prior to June 3, the soldiers were replaced with new, antagonistic RSF personnel brought in from Darfur, notable for their distinct accents, Rizeigat features, and lack of familiarity with central Khartoum.[55]

Witnesses said that this change in the composition of the security forces in and around the sit-in area was reflected in the uniforms those forces were wearing. Previously, RSF soldiers in uniform guarded the perimeter of the sit-in, and barricades manned by volunteers kept security forces out of the area used by protesters.[56] Witnesses on June 3 reported seeing soldiers in a mix of uniforms, including RSF, riot police, military police, and military special forces. Other personnel present were reported to resemble the operational unit of the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS),[57] NISS officers in plainclothes, as well as special forces wearing black. Witnesses also spoke of irregular forces deployed to the area. Ahmed, a survivor of the June 3 massacre, reported seeing security force personnel “not wearing the same uniform; some of them were wearing half of their uniforms. Some of them were wearing slippers.” Murad, a protester present at the sit-in on June 3, reported that “mostly they had traditional whips … batons, sticks, every kind of thing someone could use to attack someone…. Metal rods … they would just attack anyone they could get their hands on.”

Usman, an active protester, reported that the forces deployed to the sit-in area on June 3 included boys who appeared to be between 12 and 15 years old, wearing new, oversized riot police uniforms, “like when a child wears their dad’s clothes,”[58] and armed with pieces of metal pipe.

“They had traditional whips … batons, sticks, every kind of thing someone could use to attack someone…. Metal rods … they would just attack anyone they could get their hands on.”

Murad, a protester present on June 3, describing the security forces’ assault

Numerous interviewees told PHR that they heard rampant rumors of an impending attempt to break up the sit-in in the days prior to the June 3 violence. Several noted awareness of unusual troop movements in Khartoum, and particularly on the perimeter of the sit-in area after May 29. However, sit-in participants did not anticipate the brutality that security forces would deploy against them on June 3. In the days prior, buses reportedly dropped off large numbers of newly released criminals, riot police trainees, and RSF in areas of Khartoum North close to the Blue Nile Bridge. Many interviewees reported seeing large numbers of Thatchers[59] dispatched to areas just outside the boundary of the sit-in. Usman was a university student who had been expelled for his activism and who joined the “barricade boys,” groups of young men who guarded the barricades day and night at the sit-in after April 6. He recounted that, after crossing the Blue Nile Bridge to purchase Eid clothing in the neighborhood of Bahri on June 2, he saw “four Thatchers filled with whips…. As I walked along, there were ten Alwali coaches, and I was a bit surprised where they were going towards [North Khartoum Communications Unit of the army]…. They were wearing civilian clothes, but they looked like they were coming from a training camp. I started worrying.[60]”

In the hours prior to the attack, witnesses described hearing reports on social media and receiving phone calls alerting them to the possibility of attack, which began around 5 a.m. on June 3.

“They were so many, they looked like ants, when you’d look at the bridge, you’d just see a blue cover walking … huge amounts of them coming down the bridge towards the barricades.”

Rania, describing riot police arriving at the sit-in site

A Planned, Systematic Attack

While further investigation is warranted, the contours of what transpired on June 3 are clear. Witnesses described seeing a large mass of armed men in uniform, outnumbering the demonstrators in some areas by as many as 10 to 1. Rania, a teacher and frequent protester, described watching the riot police forces approach across the Blue Nile Bridge: “They were so many, they looked like ants, when you’d look at the bridge, you’d just see a blue cover walking … huge amounts of them coming down the bridge towards the barricades.”[61]

Interviewees described attackers wearing the regulation RSF uniform, a well-known beige camouflage with a red hat for officers, and beige or maroon hats for lower-ranking soldiers, with beige boots. Others reported seeing the NISS uniform, which is similar to but distinct from that of the RSF.[62] Some witnesses reported seeing forces in riot police uniforms of either dark blue camouflage or plain blue, with black or beige boots. At least some of these appeared to be brand new and ill-fitting. Dr. Abbas, a physician present at the sit-in on June 3 who was detained, reported being told by his captor under the Blue Nile Bridge that many of the forces were RSF personnel dressed in other uniforms because, he said, “We were too many. We did not have enough uniforms for ourselves, so we take uniforms from other forces.”[63]

Witnesses reported that many RSF could be distinguished by their features and dialect, which they identified as being from the Arab tribes of Darfur, and the Rizeigat tribe in particular. In addition to being deployed within Sudan, the RSF has reportedly brokered deals with Gulf countries for use of its troops abroad. In particular, reports indicate Rizeigat soldiers have entered into lucrative contracts with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to fight as proxies in its war in Yemen. Murad, a protester at the sit-in, recalled, “One of the ones hitting us was mad at us because he was brought from the airport immediately to the sit-in instead of being taken to Yemen.”[64]

The Massacre Begins: “It was just chaos and fire.”

When the security forces began their attack on the sit-in participants around 5 a.m. on June 3, witnesses and survivors said that army personnel at the site, who had defended civilians in past attacks from the RSF and other forces, denied protection to protesters. Witnesses reported that Sudan Armed Forces personnel had been told not to get involved if an attack against the protesters occurred, and that the army, navy, and air force had been disarmed, an allegation repeated in media reports after June 3.[65] Murad explained what happened when he and other protesters tried to access the army headquarters for refuge from the attack, as protesters had in the past. “We started pleading to provide us any help, to let us in, and they said, ‘We’re sorry, there’s nothing we can do today.’” Witnesses also described senior army officers ordering the junior officers to surrender the protesters to the RSF. Naseem, a student activist present at the sit-in on June 3, reported that army soldiers were escorting him and other protesters away from an area where RSF and riot police were burning tents and stacking bodies.[66] Naseem explained that a higher-ranking officer receiving orders by walkie-talkie instructed the army officers not to protect them. e added, “He told the officers to move away from us, the heartbreak was evident in their faces, but they couldn’t react and just moved,” allowing the RSF forces to beat him and others. Another witness, Karim, described the scene at the sit-in: “All the tents were burnt. They took over. The forces took over, it was just chaos and fire. They came around us and beat us.”[67]

Beaten and Blinded: Adam’s Story

Adam[68] was a 36-year-old professional who was fairly active during the protests before April 6. Beginning April 6, when the sit-in was established, he became more active, staying in the large tent set up for people from his neighborhood. During this period, prior to June 3, he experienced tear gas and other crowd-control weapons and was shot at with live bullets.

Adam was present the morning of June 3. He heard reports on social media around 2 a.m. that security forces were going to disperse the protests. By 5:15 a.m., he witnessed what he estimated were two hundred white pick-up trucks known as Thatchers enter from Mak Nimir Bridge, each carrying security forces in RSF uniform. Adam described seeing approximately the same number of Toyota pick-ups enter after them, transporting security forces in blue riot police uniforms. He explained, “I headed to Nile Street, and walked on the high railway toward Blue Nile Bridge. I saw a huge force of riot policemen entering the sit-in area. It shook me…. They wore the blue camouflage uniform and they stood up on the railway.” Adam noted the leader was holding a gun, but the rest were armed with sticks.

He heard and saw bullets being shot. While people were running away, a small group, including Adam, started throwing rocks at the forces while hiding by the side of the Continuing Professional Development Center. The leader fired at this group and they began to run. While fleeing toward the main stage near the army headquarters, Adam fell into a hole full of rainwater. He got up, dripping wet, and an assailant in riot police uniform beat him on the back with a stick. He escaped but stumbled on the sidewalk when he tried to look back while running and fell again. RSF forces surrounded him. He recounted, “They made a circle of seven or eight soldiers around me, hitting me at the same time, with whips, sticks, and water hoses, for more than 10 minutes.” He sustained three blows to the head and was beaten on his back, legs, and arms; bones in both his hands were broken while he was trying to protect himself. Adam described the sensation of being struck in the eye with a traditional whip: “I closed my eye and felt like something was wrong.… One of them kicked me from the back so it was hard for me to breathe and walk.” He estimated that this beating occurred at 6 a.m. The attackers in riot police uniform instructed him to leave after they tired of beating him.

“They made a circle of seven or eight soldiers around me, hitting me at the same time, with whips, sticks, and water hoses, for more than 10 minutes.”

Adam, who suffered multiple broken bones at the hands of the RSF

Weak, bleeding, and confused, Adam limped toward the Mak Nimir Bridge, where he had seen the trucks enter. He hid in a tent and wrapped himself in a carpet. A different RSF officer discovered Adam hiding there and ordered two other protesters to help hold him up as he walked to Nile Street. “On the way my phone and keys were taken. I arrived at Nile Street and found a lot of injured people. One person was laying on his stomach in his vomit; I didn’t know if he was dead or alive.” He estimated seeing hundreds of injured detainees at the site, including older women and children, being kept there by RSF soldiers armed with whips and sticks. Adam was physically unable to mount the large truck that had come to transport injured people, so he was placed in an ambulance and taken to Omdurman Military Hospital at around 7 a.m. at the Military Hospital, he received treatment for a large laceration on his forehead and several others on his scalp. His left eye was cleaned and bandaged, but no ophthalmologists were available to attend to the tears in his cornea and retina. His arms were both swollen and X-rays taken several days later at Feda’il Hospital confirmed multiple fractures in his hands.

Adam was unable to receive necessary surgery in time to save his sight, and explained, “The doctor told me I was too late. He told me if I came earlier it could be treated but that will not work now.”

Clinical examination confirmed that Adam’s visible scars and injuries are consistent with defensive wounds from blunt trauma, highly consistent with beating from sticks, whips, and water hoses. He sustained fractures in his hands, lacerations over his forehead and scalp, and severe trauma to his eye causing vitreous hemorrhage and retinal detachment and resulting in permanent vision loss in the left eye.

Targeted Violence Against Health Care

The June 3 assault continued a pattern of attacks on health care providers, institutions, and patients, as well as prevention of access to care at nearby hospitals. Relevant violations against health workers – whose ethical duty is to treat the sick and wounded without discrimination – and interference with health infrastructure and delivery of medical care included the imposition of siege-like conditions on health facilities; restricting ambulances and other vehicles from transporting injured protesters to health care facilities; and beating or shooting health care workers, patients, or visitors who tried to enter or leave health care facilities on foot. This animus toward health care workers and facilities may reflect the security forces’ recognition of the role that health care workers, and particularly doctors, have played in pro-democracy protests in Sudan since December 2018. PHR documented in its April 2019 report that at least 136 physicians were arrested and detained as a result of providing care to protesters, making statements supporting the protest movement, or participating in protests.[69] Doctors were arrested while participating in protests, working in hospitals or clinics, and in their homes.

Targeting Doctors

RSF forces specifically targeted doctors and other health care workers with harassment, intimidation, and violence on June 3. Dr. Abbas, a young doctor captured by the RSF while hiding with others on the roof of the University of Khartoum Clinic, reported that when he was forced to show his identification, the soldiers said, “Oh, so you’re a doctor.” They then yelled at him:

“You’re the reason for all this chaos and this whole mess … you’re the reason why the country’s like this, you’re the reason why we kill people, you’re the reason why people die, you’re the reason, you’re the reason!”[70]

The RSF soldiers then separated Dr. Abbas from the other detainees, saying, “This is a doctor so we’re gonna deal with him on his own.” Two soldiers pointed automatic weapons[71] at him and marched him to a nearby shaded area with trees, where they continued to berate him:

“They were yelling at me again like, ‘You’re the reason, you did this, you got us here, you’re the reason we don’t get sleep anymore, you’re the reason we work all the time, you’re the reason, you’re the reason’ and I just basically said my Shahada (prayer) … they took off my glasses from my face and threw them on the ground. Then they just stepped on it, [saying] ‘You’re not going to see anything today, this is the last thing you will see.’”[72]

He reported that the commanding officer came back and asked if he was a doctor, saying, “Leave him, we’re not going to do anything to him today, today is not his day.” Dr. Abbas was then brought to a detention area under the Blue Nile Bridge, where he was required to care for wounded protesters.

Ahmed, trained in first aid and active in providing frontline care to protesters during the sit-in, reported how RSF personnel singled him out from other detainees for specific, targeted torture while detaining him in an empty office building because they mistakenly believed he was a doctor. He said, “They grabbed me down to the floor.” The soldiers then used a pocketknife to re-open a healed surgical scar. Ahmed described how they then made him lie on his back, saying, “Oh, you’re a doctor … OK, we will let you know how we treat bleeding outside the capitol.” The RSF soldiers lit cigarettes, took a few puffs, and put them out in the incision they had made.[73] Ahmed’s physical examination was highly consistent with his description of these events, with cigarette burns and multiple healing bruises and abrasions corresponding to his description of multiple beatings and burns adjacent to a laceration.

Dr. Asim, an orthopedic surgeon treating trauma patients on June 3 at Royal Care International Hospital, reported that on the day after the June 3 massacre, security forces detained fellow physicians returning to their homes from the hospital:

“The level of suppression was unbelievable … the roads were already all barricades and blocked, but anything that proves that you are a doctor you’d have to hide … we heard that some of our colleagues were on their way home, and were arrested on the way just because they are doctors.”[74]

“The level of suppression was unbelievable … the roads were already all barricades and blocked, but anything that proves that you are a doctor you’d have to hide … some of our colleagues were on their way home, and were arrested on the way just because they are doctors.”

Dr. Asim, reporting on security forces’ targeting of health professionals

Forced Medical Care in RSF Detention

Witnesses reported that the RSF forces on June 3 forced physicians to work while held in detention after the dispersal of the sit-in. Dr. Abbas recounted how RSF personnel brought him with other doctors to an RSF site under the Blue Nile Bridge. The RSF soldiers screamed at him, “Aren’t you a doctor? You’re going to save these people.” Dr. Abbas explained that “the doctors with me … were beaten up as well … but almost all of us doctors could function, so we started helping patients.” He was detained there for seven hours, providing treatment at the direction of an RSF doctor, with RSF-provided medical supplies. Dr. Abbas reported that during this time he saw four critically injured patients transferred to Omdurman Military Hospital in military ambulances.[75]

Attacks on Informal Sit-In Clinics

aid to protesters, was detained and

tortured by Rapid Support Forces

soldiers, who cut open a healed scar

(visible at the left middle of the photo)

and then extinguished lit cigarettes in

and around the open wound. Ahmed’s

physical examination by a PHR clinician

was highly consistent with his narrative,

with cigarette burns and multiple

healing bruises and abrasions.

PHR interviewed multiple health care workers and former patients who worked in different clinical settings inside the sit-in.[76] All described similar patterns of violent behavior by security forces on June 3: attacks on medical staff, and patients, and the creation of threatening and insecure conditions in and around areas designated for medical treatment.

Security forces attacked the makeshift clinics that had served the sit-in population, including those inside the protester care center staffed by volunteers housed inside of the University of Khartoum Clinic. Other well-staffed clinics were attacked, including one at the Continuing Professional Development Center (CPD) near the navy headquarters and the makeshift medical clinic in the Electricity Building near the navy headquarters. Security forces also attacked smaller, less permanent medical stations, including two organized by Ahmed near the Blue Nile Bridge, and one located inside a small campus mosque near Nile Street.[77]

Dr. Abbas observed the attack on the University Clinic by RSF forces wearing riot police uniforms as he hid on a rooftop nearby: “They broke [into] almost all the rooms; you could hear glass shattering, people screaming afterwards, and then you hear them threatening [people] to get out or they’re going to shoot them.” He and his fellow protesters were eventually discovered. The RSF soldiers stole their belongings and beat and detained them.[78]

Dr. Yaseen, a general surgeon, was in the CPD clinic around 6 a.m. on June 3 preparing to perform surgery on a protester with a head wound when a bullet pierced a window near the ceiling. The bullet narrowly missed Dr. Yaseen but struck his patient’s chest, killing the patient. Despite his outrage, Dr. Yaseen maintained his ethical obligation to treat the sick and wounded without discrimination throughout the morning, treating an injured RSF soldier in civilian clothes. Dr. Yaseen explained, “He said ‘I belong to the RSF but I’m not happy about what they are doing…. We must move on to a civilian government.’ Then I started to treat him because I’m a doctor at the end.”[79]

Munir, a protester at the sit-in on June 3, described seeing large numbers of wounded brought to the clinic in the Electricity Building with wounds from live bullets. He noted that many of them were already dead upon arrival.[80] Usman, the student who had joined the ranks of the “barricade boys” defending the sit-in, was shot multiple times in the right thigh on June 3. Usman was brought by fellow protesters to the Electricity Clinic several hours after the attack began. While receiving IV fluids and resting on a cot, he watched a “large force” of RSF storm the Electricity Clinic:

“They broke [into] almost all the rooms; you could hear glass shattering, people screaming afterwards, and then you hear them threatening [people] to get out or they’re going to shoot them.”

Dr. Abbas, describing an RSF attack on the University Clinic

“We were around seven injured, and there were children hiding under a table … people hiding inside the Electricity Building to protect themselves.… [The RSF] entered with whips and started hitting everyone randomly.”[81]

Usman described how, during the raid, a protester applied pressure to Usman’s gunshot wounds “at the same time the RSF were beating him.” Eventually an SAF captain arrived and ordered the RSF soldiers to stop torturing the detainees and “made them leave.”

Attacks on Hospitals

The RSF attacked multiple hospitals during the June 3 massacre, preventing access to care for injured protesters and severely restricting the flow of medical supplies and health care worker access.[82] The World Health Organization issued a statement that the violence to hospitals in Khartoum “resulted in emergency services being shut down, the unwarranted transfer of patients, injuries to five medical staff and patients, and threats to others.”[83] The Central Committee of Doctors reported on June 9 that the RSF targeting of medical personnel had led to the closing of eight hospitals.[84] PHR interviewed multiple witnesses, including former patients and care providers, who confirmed the impact on Moallem Hospital and Royal Care International Hospital. Other witnesses reported observing a security force presence while receiving treatment at Omdurman Military, Feda’il, Imperial, and al-Saha hospitals.

Verifying an Assault on Health

PHR’s research partner, the Human Rights Center Investigations Lab at the University of California, Berkeley, identified the following verified examples of video documentation of violence against health care perpetrated in Khartoum on June 3:[85]

Attack on Royal Care International Hospital

On June 3, security forces attempted to enter the Royal Care International Hospital, blocking access for ambulances carrying injured protesters, attacking medical staff, and firing into the hospital. Forces ordered the hospital staff to evacuate protesters. This video uploaded to Twitter shows soldiers arguing with doctors and hospital staff, beating a man on the hospital grounds with a stick, and then walking quickly toward the hospital entrance.

Violence at Al-Moallem (Teaching) Hospital

On June 3, security forces chased protesters into al-Moallem Hospital grounds and beat them. Reports detail forces preventing ambulances from dropping off wounded protesters at the hospital. This video on Twitter, tweeted by the television channel al-Jazeera Mubasher, shows a man inside Moallem Hospital compound being beaten with sticks by security forces.

Al-Moallem Hospital

PHR interviewed survivors who were in or around al-Moallem Hospital on June 3. Several described al-Moallem as effectively besieged by forces wearing RSF, riot police, and black military uniforms. These forces prevented patients and treating physicians from accessing the hospital by beating, detaining, and threatening them. All interviewees mentioned attempts by the security forces to raid the building, although some expressed their belief that the nearby presence of the army intelligence headquarters forced the RSF to exercise restraint. Dr. Amina, who had fled with colleagues to al-Moallem, reported that forces wearing RSF and riot police uniforms “tried to break in three times.”[86] While the role of the army in the June 3 attacks on health care require further investigation, some witnesses reported violent clashes between members of the army and the RSF near hospitals. For example, at 6 a.m., Dr. Yaseen reported seeing a Sudanese army officer in military uniform being beaten by RSF outside the hospital.[87]

Mu’min, an attorney at the sit-in, described the injuries security forces inflicted on him at the Clinic Gate at the University of Khartoum campus: “They started attacking me because I was carrying a phone…. Five of them surrounded me and [were] hitting me with sticks.”[88] Mu’min was rescued by protesters who threw rocks at his assailants, but he fell while running and lost consciousness. He vaguely remembers someone taking him for admission to Moallem Hospital at 5:20 a.m. on June 3 for a hand injury and eye laceration.

Dr. Amina explained that she fled towards al-Moallem after witnessing gunshot fatalities: “I could hear the barricade boys shouting, and … I started seeing people falling.” She added that the shots were coming “from above” and caused protesters to flee toward the hospital. Dr. Amina recounted that the RSF attacks on the clinics outside the main hospital building began around 6 a.m. and resulted in the destruction of an area for conducting magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a costly and sophisticated diagnostic technology.[89]

Inside the hospital, Dr. Amina described how terrified people hid under the reception table in the lobby while the sounds of shooting and screaming continued outside. “After a while, there was no fewer than 700 persons in the hospital … [and] about 300 injuries. At about seven or eight a.m. we had seven martyrs at the hospital. Five of them were known, and two were unknown.” (Protest fatalities in Sudan are commonly referred to as martyrs, because they died for their belief in civilian rule).[90] While the circumstances of each of the dead held at Moallem are not clear, several witnesses recounted bringing injured people for care who died upon arrival. Jamal, a teaching assistant active in the protests and present on June 3, reported finding the prominent 26-year-old activist Mohammed Mattar shot dead,[91] and bringing his body to al-Moallem.[92] He also reported seeing two people injured by shots fired by forces surrounding the hospital.

As the siege of the hospital continued throughout the day, it interfered with medical treatment, including transfers to better-equipped hospitals. Moneim, a protester who had accompanied injured friends early in the morning to al-Moallem, described hiding there for 12 hours with acquaintances from the sit-in, including a 15-year-old boy who had sustained a gunshot wound to his arm.[93] By 11 a.m., the surrounding RSF and riot police forces beat anyone who tried to enter or leave al-Moallem, blocking access of injured protesters to medical treatment and functionally closing the hospital. Dr. Amina reported that there weren’t enough medical supplies or staff to take care of all the injured people who were stuck inside.[94]

trying to save a gunshot wound victim

who died in his arms. He was carried to

al-Moallem Hospital, which was attacked

by security forces as he arrived. PHR’s

clinical examination of Suleiman showed

bullet entry and exit wounds consistent

with his report of being shot while trying to

run away

Suleiman, who had been shot in both hips while trying to save a gunshot wound victim who died in his arms, was carried to al-Moallem by other protesters. He witnessed RSF forces breaking the door to al-Moallem hospital; after they withdrew, fellow protesters carried him inside, where he reported seeing a fellow patient with “his stomach cut open” and another with multiple gunshot wounds to the chest.[95] Because there were insufficient medical staff and supplies to deal with the severity of his wounds, Suleiman was transferred to al-Saha hospital by ambulance. He reported that al-Saha was “also surrounded by RSF and they tried to get into it multiple times.”[96]

“[Forces] carrying whips and in police uniforms … tried to attack the hospital. One of them shot tear gas … they were trying to kick down the doors.”

Bilal, an injured protester, describing the assault on Moallem Hospital

While hiding on the grounds outside the hospital compound, Murad described seeing armed men on “the rooftops that were around us … [with] long-range firearms weapons, AK 47s, and sniper rifles.” Murad recounted watching protesters run inside al-Moallem, while being pursued by “people … wearing black uniforms, special forces, uniforms of policemen, different uniforms of police, purely blue, blue and black. Some of the group we were with ran into the al-Moallem Hospital and were followed by forces of different uniforms…. I saw forces running into the hospital holding sticks and batons.”[97]

Bilal, a protester who had sustained a bullet graze wound, witnessed the assault on al-Moallem from nearby, while hiding inside a compound wall. He said forces “carrying whips and in police uniforms … tried to attack the hospital. One of them shot tear gas … they were trying to kick down the doors.” Bilal made it inside the hospital after the troops sought another entrance. Once he was let in, he said,

“They closed the doors with sacks of sugar; … someone immediately came to wrap up my wound.… there were no beds or anything, the entire hospital was basically just blood everywhere. They stitched my leg on the ground, without anesthesia, there was none.”[98]

Dr. Amina recalled that, even after the shooting subsided, RSF forces remained, with no guarantees of safety for health care workers or patients:

“Although the gunfire stopped around 3:00 or 3:30, no one left the hospital because they [RSF] were standing outside. After that, a young man from the Army Intelligence came and said people can go out. I said to him that we can leave the hospital, but can you guarantee the safety of these people? He said no.”[99]

Royal Care International Hospital

Royal Care International Hospital received transfers of critically injured protesters from al-Moallem. Emergency Medicine specialist Dr. Haitham was treating patients there, and explained, “In the early morning we were contacted and told that there are a lot of injured people starting to arrive at Royal Care Hospital.” Witnesses and staff members reported that armed forces wearing RSF and riot police uniforms surrounded the hospital and prevented the injured from accessing it, as early as noon.[100] By later afternoon, Royal Care International Hospital was surrounded by RSF pursuing protesters fleeing the sit-in site who were seeking safety in the hospital. Dr. Asim, an orthopedic surgeon who worked at Royal Care on June 3 because both al-Moallem and Imperial Hospitals were inaccessible, reported that what provoked the RSF to come and beat up people at the hospital was that “they saw people leave al-Qiyada (the central sit-in area) and come into Royal Care Hospital.”

Witnesses and staff members reported that armed forces wearing RSF and riot police uniforms surrounded the hospital and prevented the injured from accessing it, as early as noon.

Dr. Asim described the aggressiveness of the RSF troops outside the hospital:

“[W]hen we were giving emergency aid … we had people (medical staff) stand in front of the hospital emergency gates at Royal Care [to prevent RSF intrusion into the premises], and [the RSF] would come and beat them.”

Dr. Asim noted, “[Injured protesters] couldn’t come into Royal Care,” which forced patients to go to other hospitals nearby. He described how the Royal Care ground floor was “filled with patients,” and that an RSF soldier “wanted to fire an RPG [rocket propelled grenade] at us at the hospital” but was stopped by an officer.[101]

Abdelaziz, a medical services coordinator working with protest organizers, described how forces in blue camouflage uniforms flooded the streets surrounding Royal Care, attacking those trying to approach and blocking people from entering the hospital. When he was able to enter the hospital, Abdelaziz and his colleagues attempted to collect data on the numbers of injured. He noted, “When we finally … did the information gathering … it was around 380-something injured people on that day, just in Royal Care.”[102]

“They told us that if the protesters were not evacuated from the hospital within two hours, they would use aggressive force, even shooting and killing.”

Dr. Haitham, reporting on RSF demands at the Royal Care Hospital

A member of the Royal Care medical team, Dr. Haitham, told PHR that the RSF forces demanded that the medical director at Royal Care evacuate all protesters sheltering inside the hospital: “They told us that if the protesters were not evacuated from the hospital within two hours, they would use aggressive force, even shooting and killing.” The medical director responded by instructing the protesters to leave the building “out the back door.” Dr. Haitham reported that despite the hospital complying with the evacuation order, RSF forces continued to surround it for two days, firing so much tear gas that he could feel its effect inside the building.[103]

Extrajudicial Killings

While the total number of dead from the sit-in massacre remains contested, many activists and organizations have compiled lists of civilians reportedly killed on June 3. On June 6, 2019, Sudan’s Ministry of Health acknowledged 61 deaths,[104] although by June 27 it had acknowledged 87.[105] In contrast, a Sudanese lawyers association in the United Kingdom lists the names of 241 dead.[106] Based on eyewitness reports of shootings, including from people injured on June 3, PHR believes that the larger number of fatalities is more accurate. Reports of dozens of alleged enforced disappearances by security forces on and following June 3 could increase the death toll if more victims are discovered. Interviewees reported witnessing the extrajudicial killing of individuals, as well as seeing dead bodies in streets or clinical settings. For example, Ahmed reported giving first aid to “a man who died in front of me while I was treating him from a direct gunshot in his heart.” He also recalled seeing two dead women, although he noted that identifying the gender of corpses was difficult because their heads were covered “with clothes.”

“I saw bodies scattered around the gardens to the left and right, nearby the main road, with blood all around.”

Ahmed, describing the 37 dead bodies he counted near the University of Khartoum gates

In total, Ahmed counted 37 dead bodies lying near the main gate of the University of Khartoum, as he fled the sit-in area. He explained, “I saw bodies scattered around the gardens to the left and right, nearby the main road, with blood all around.”[107] In some cases, witnesses knew those they saw killed, such as Suleiman, who personally knew many of the young male activists killed that day. More often, witnesses described the dead as fellow protesters fleeing the attack. A member of the medical community provided PHR a morgue census of 71 bodies for the week of June 3 through 6.[108] Although this record does not represent all deaths resulting from the sit-in massacre, an independent analysis prepared for PHR indicates that most deaths on the list were due to violence: gunshot wounds were the primary cause of death in 72 percent of cases, including 10 children under the age of 18, the youngest of whom was six years old. The second most frequent cause of death was stab wounds (20 percent).[109]

Table 2: Sample of Mortuary Admissions, Greater Khartoum Area, Sudan June 3-6, 2019

| Reported Cause of Death | Number | % |

| Gunshot Wounds | 51 | 71.8% |

| Stab Wounds (Sharp Force) | 14 | 19.7% |

| Drowning | 3 | 4.2% |

| Traffic Accidents | 1 | 1.4% |

| Run Over | 1 | 1.4% |

| Crushed Skull (Blunt Force) | 1 | 1.4% |

| Combined (Sharp/Blunt) | 0 | 0% |

| Undetermined | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 71 | 100% |

Multiple witnesses reported their impression that much of the shooting was from the rooftops or elevated structures such as the railway or the al-Bashir Medical City Center.[110] Ahmed described watching a soldier in black uniform shoot protesters with a weapon outfitted with a sniper scope near the army headquarters.[111] Usman watched two snipers position themselves on the railway near the Blue Nile Bridge. He saw one of them shoot an unknown protester in the head and noted, “Around sunrise, I began to hear the sound of the bullets hitting the metal close to me.”

Ahmed described watching a soldier in black uniform shoot protesters with a weapon outfitted with a sniper scope near the army headquarters. Usman watched two snipers position themselves on the railway near the Blue Nile Bridge. He saw one of them shoot an unknown protester in the head.

Usman reported that later in the morning he was with a group of friends attempting to defend the sit-in by throwing rocks. When he stood to look for his friend who had advanced toward the Blue Nile Bridge, a different sniper in black positioned on the top of a tunnel nearby shot him in the right leg.[112] Dr. Haitham noted that the sniper bullets removed from patients on June 3 at Royal Care were “quite big compared to those of the M16 [an assault rifle designed to provide maximum firepower].” He described the types of injuries Royal Care received the morning of June 3:

“I arrived there around 7:30 a.m. A lot of patients started coming to the ER with different types of injuries … gunshot to the lower limb, to chest, even the head…. I cannot recall the exact number actually, but most were in the lower limb…. We made a triage area according to the severity. When Royal Care hospital is full (around 40), we move the rest of the patients (30 or more) to al-Saha Hospital.” [113]

Dr. Yaseen described the injuries he was forced to treat near the Blue Nile Bridge on June 3 while he was detained there:

“What was strange is that they didn’t shoot in the limbs … in the arms, in the legs, no. They were shooting either directly to the chest or to the head…. Even the tear gas should not kill you, but rather than using the tear gas just to shoot in the air, no, they shoot directly to the head.”[114]

Multiple witnesses saw RSF soldiers shoot unarmed protesters. Murad, who was also at the Blue Nile Bridge detention site, reported seeing a fellow detainee shot under the Blue Nile Bridge:

“There was this guy shouting and screaming ‘What are you doing?’ He was very angry and traumatized…. I looked at them [RSF] and then I saw him get shot…. Then even the floor we were sitting on, our pants, our clothes, were covered in blood.”[115]

Suleiman described carrying a man in his 40s whom he had seen shot: “We reached the Resilience Barricade and this person I was carrying became very heavy and his mouth was bleeding. He passed away.”[116]

Excessive Use of Force, Torture, and other Cruel, Inhuman, and Degrading Treatment

Sudanese authorities have claimed that the events of June 3 were part of an effort to “clean up” the reputed drug dealing area north of the sit-in, known locally as “Colombia.”[117]

Multiple witnesses reported that conditions in the area did not justify the use of force; even had force been justified to dispel illegal activity, the force was excessive, in that it was not necessary or proportionate, and extended far into the area of the sit-in.

Survivors of the sit-in massacre reported being assaulted with tear gas, rubber bullets, whips, sticks, batons, rifle butts, and pieces of pipe. Gunshot wounds on victims of the violence revealed that security forces deployed live ammunition against these unarmed civilians.[118] Interviewees reported seeing uniformed security forces personnel, men in civilian garb carrying assault rifles, and snipers on rooftops.

As demonstrated in the table below, half of the 30 people interviewed had injuries with visible scars. A third sustained gunshot wounds, and two-thirds experienced blunt force trauma. Almost a third of those injured had permanent disabilities.

Table 3: Injuries, Disabilities, and Symptoms among 15 respondents with Physical Injuries

| Age Group | 0-17 | 18-29 | 30-45 | All |

| Number of People Injured with Physical Injuries | 1 | 11 | 3 | 15 |

| Gun Shot Wounds | 1 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| Blunt Force Trauma | 0 | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| Permanent Disabilities | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

One of the victims of that excessive use of force was Muna, a sit-in participant. Muna was hiding from security forces with four other young women in the University of Khartoum clinic. A group of RSF, led by a helmet-wearing soldier in a black uniform carrying a large gun, broke into the clinic and beat them:

“[T]hey started beating us up…. He was beating me on the head and beating all of us a lot…. [Using] a baton, some others were carrying whips, and … thin sticks, they were beating us everywhere, they didn’t care what part of the body it was, whether it was the head or the body.… They were fighting within each other, saying ‘Take them outside, let them kill them,’ and others were saying ‘No leave them here,’ there was a good cop, bad cop situation.”[119]

Survivors of the sit-in massacre reported being assaulted with tear gas, rubber bullets, whips, sticks, batons, rifle butts, and pieces of pipe. Gunshot wounds on victims of the violence revealed that security forces deployed live ammunition against these unarmed civilians.

Rania, a teacher who had participated in the sit-in and other protests since April 6, described being beaten by uniformed soldiers while attempting to find shelter in the nearby navy headquarters:

“We headed toward the Navy quarters to try and get inside…. At a point, RSF men came down off of their trucks with their sticks and started beating us with them…. We were getting beaten for a while there, then some army soldiers came out and told us to just leave.”

Rania then recounted how she ran through the streets in an effort to escape the beating, but eventually collapsed:

“I had my arms up to cover my head until they were broken … a broken bone on my left hand, and a broken wrist on my right…. I felt like something was wrong with my hands, but I didn’t know what was going on, my arms fell to my sides, so I just kept running…. Since the first hit, my entire body went numb, so I didn’t feel all those beatings. The last hit I got was in the face, I could taste blood and that’s when I fell.… RSF soldiers would walk by and antagonize me, saying ‘I thought you said you wouldn’t leave the sit-in,’ and they kicked and stepped on me.”[120]

Dr. Abbas described hearing beatings while hiding on the roof of the University clinic: “You can hear them screaming, and then you can’t hear them anymore. Some people were begging for them to stop.” Dr. Abbas reported that, later in the day, he treated injuries caused by severe beating with batons and “the backs of guns” (rifle butts, or dibshik):

“[T]he minimum injury is … [a] broken arm or lashes on the back, like very deep [abrasions] .… Some of the patients had both arms broken … an arm or a leg or two legs broken…. Some had all their limbs broken.”[121]

Multiple interviewees reported that pregnant women miscarried as a result of beatings. Murad described seeing the RSF in the detention area under the Blue Nile Bridge beating a visibly pregnant women of “darker ethnicity” with “very African features,” and therefore more likely to be targeted. He recounted,

“Some of these soldiers were holding whips and beating her up, asking who the father is. And then one of the doctors [being forced to work in the detention area] said, ‘She’s gonna go into labor. Leave her, she’s gonna go into labor.’ And then they were like ‘Who cares about this bastard child of this woman?’ And they continued beating her up until she lost consciousness.”[122]

I had my arms up to cover my head until they were broken.… Since the first hit, my entire body went numb, so I didn’t feel all those beatings. The last hit I got was in the face, I could taste blood and that’s when I fell…. RSF soldiers would walk by … and they kicked and stepped on me.”

Rania, who was beaten by RSF soldiers while trying to flee

Samir, an active protester, witnessed the RSF shaving the dreadlocks of six young men near Feda’il Hospital, and was himself shaved at a checkpoint after being questioned about his participation in the sit-in. He explained, “They shaved me with a pair of scissors. For some other people it was a razor, for some other people it was a knife.” [123]

Murad described seeing an acquaintance whose dreadlocks were ripped out by hand, while he was beaten: “Some of them were pulled out of his head when they brought him in. You could tell some of the bones in his arms were broken. The bones were not straight.”[124] Mustafa recalled seeing soldiers wearing the RSF uniform with red caps stop cars and force people to get out for beatings near Mak Nimir bridge. He heard soldiers say, “[Y]our hair is long,” and then give the order to administer “30 lashes with sticks and cut his hair.”[125]

Intimidation, Humiliation, and Ethnic, Racial, Religious, and Sexual Insults

In addition to beatings, interviewees reported that security forces forced them to do and say things designed to humiliate them under threat of physical violence. Witnesses reported watching RSF forces strike detained protesters with sticks, batons, rifle butts, and whips and force them to say “Askariya” or “Military rule” as an act of symbolic submission. Some of these interactions indicate the attackers’ allegiance to Hemedti and their status as RSF troops drawn from the ranks of the Janjaweed militia. Dr. Abbas described RSF officers insisting that he say “Janjaweed,” explicitly referring to the role of the Rizeigat Abbala in the paramilitary from which the RSF emerged:[126]

“They wanted me to say Janjaweed and I [said] … ‘I know only Rapid Support Forces … I don’t know, what do you call yourself?’ ‘Janjaweed.’ And then he asked me again, ‘What do you call [Hemedti]?’ I [said], ‘Vice President’…. [I asked] ‘What do you call him’… He [replied] ‘ra’iy abl (camel herder).’”[127]