Executive Summary

On June 4, 2020, the New York City Police Department (NYPD) used force against protestors of police violence, arresting 263 people in the Mott Haven neighborhood of the South Bronx. Mott Haven is a predominantly Black and Latinx community that historically has experienced high rates of poverty and homelessness. Since March 2020, the community has also faced high rates of infection and death from COVID-19. For many years, both the overall community and individuals living within the community have endured the deleterious effects of systemic racism, including from over-policing.

The Bronx Defenders, a Bronx-based legal assistance nonprofit organization, is representing 23 of the Mott Haven protestors, each of whom was detained and arrested by the NYPD. These 23 people are members of the Mott Haven Collective that is now calling for the City of New York to pay reparations to the community due to the June 4 police violence. In December 2020, the Bronx Defenders asked Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) if it would be willing to provide an analysis of the physical and psychological sequelae of the individual and community-level trauma stemming from these police actions; this was to be done using the relevant facts described by these 23 protestors regarding their reported experiences, including an analysis of both mental and physical harms.[A] PHR’s medical and psychiatric experts conducted an independent assessment of these individuals’ Notices of Claim and prepared this report analyzing these and other factors.

The PHR experts addressed five key questions in this report. First, were there patterns and types of traumatic events experienced at the hands of the NYPD and, if so, to what extent? Second, to what extent were these patterns consistent with the scientific literature about individual mental health harms that result from witnessing or experiencing police violence and mistreatment? Third, did PHR’s experts find that there were ongoing mental health symptoms resulting from this trauma after reviewing the Notices of Claim, and to what extent did these relate to the diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and psychological distress? Fourth, what scientific literature on community trauma is relevant for assessing the community effects of the NYPD actions on June 4, 2020? And, finally, did PHR’s experts believe that there were general principles that should guide necessary individual and systemic responses to address the harms sustained by both individual protestors and the broader Mott Haven community?

Preliminarily, it needs to be noted that the PHR medical and psychiatric experts cannot offer formal diagnoses, because actual clinical interviews or examinations have not been conducted. However, a thorough review of the documentation provided does lead to the conclusion that all of the claimants describe having had exposures to traumatic events consistently reported as being caused by actions of the NYPD. In our opinion, these meet the diagnostic criteria in the American Psychiatric Association’s most recent edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). “Traumatic events” are defined as an exposure to “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence in one (or more) of the following ways: 1. directly experiencing the traumatic event(s); 2. witnessing, in person, the event(s) as it occurred to others; 3. learning that the traumatic event(s) occurred to a close family member or close friend. (In cases of actual or threatened death of a family member or friend, the event(s) must have been violent or accidental); 4. experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s).” The 23 claimants all describe experiencing physical, mental, and/or verbal abuse directed at them and witnessing these abuses against other people. All 23 protestors were subject to the threat of serious injury, with several explicitly expressing their fear of being killed by police. Twenty-two of the protestors themselves described experiencing direct violence against them. Our analysis concluded that there was a total of 84 events.[B]

People who are exposed to traumatic events are at elevated risk for multiple mental health symptoms compared to those with no traumatic exposures. Both the severity of risk and the type of exposure matter. The large and growing body of rigorous evidence from the scientific literature that the report reviews demonstrates that both experiencing police violence and witnessing police violence are independently associated with poor mental health and, at times, poor physical health. The literature further indicates that the “police” in “police violence” may bestow a specific heightened meaning that extends beyond the violence and the threats of violence itself. Nineteen claimants describe experiencing cardinal symptoms of PTSD, depression, or anxiety since the events at the Mott Haven protest, with some describing symptoms consistent with all of these conditions.

Such police violence, as occurred in Mott Haven, can impair the communities in which it occurs, thereby producing community trauma. When perpetrated against predominantly Black, Latinx, and other marginalized communities in the United States that have historically suffered disproportionately from experiencing and witnessing police violence, such violence further compounds collective trauma. The resulting individual and community harms can have broad effects on community members, including negatively affecting community trust and cohesion, overall well-being, and social bonds.

In the opinion of PHR’s experts, the harms sustained by both individual protestors and the broader Mott Haven community require both individual and community-wide responses. There should be redress for the individual protestors. There also should be measures to address the community spillover effects, where members in the surrounding community who did not take part in the protest may experience psychiatric sequelae from the police actions on June 4, 2020, as well as the damage to intra-community and community-government relations. Interventions aimed at reducing the burden of trauma and its outcomes should also include bystanders and other observers in addition to those directly affected. Effective responses should also directly address collective trauma. The report concludes with recommended principles to guide meaningful and, in our opinion, necessary actions.

Section One: Introduction

The May 25, 2020 police killing of George Floyd sparked a wave of public demonstrations across the United States and around the world. George Floyd’s murder occurred soon after other police killings and compounded the loss Black and Brown communities had experienced due to the disproportionate rates of COVID-19 infections and deaths among Black and other communities of color. In the United States, hundreds of thousands of people across the country joined in public Black Lives Matter (BLM) demonstrations to demand an end to systemic racism, racial inequities, and police violence.

On the evening of June 4, 2020, an anti-police violence demonstration began in the Mott Haven neighborhood of the Bronx borough of New York City.[1] Just before 8:00 p.m., when a curfew imposed by the city would take effect, the New York Police Department (NYPD) encircled (“kettled”) approximately 300 protestors who had been marching and prevented their dispersal. Shortly after 8:00 p.m., police officers climbed onto vehicles, punched, kicked, and beat people with batons, threw people to the ground, dragged people through the streets, and launched chemical irritants and kinetic impact projectiles. The NYPD conducted mass arrests, with a reported 263 people arrested, including legal observers, medics, and essential workers.[2] At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York, law enforcement officials crammed large groups of people into transport vans and into small holding cells for hours, and removed facial masks of some of the detained. Many police officers were reportedly not wearing masks.[C] There were reports of absent, blocked, and delayed medical care for protestors’ injuries.[3]

We have been asked to provide an independent expert opinion on physical and psychological sequelae of individual and community-level trauma stemming from these police actions (see attachment A for our qualifications). We have conducted an independent assessment of the Notices of Claim from 23 people who attended the June 4, 2020 Mott Haven protests and were detained and arrested by the NYPD. These 23 people are members of the Mott Haven Collective and are represented by The Bronx Defenders, a non-profit legal assistance organization based in the Bronx. On January 26, 2021, the Mott Haven Collective sent a demand letter to the City of New York calling for the creation of a community reparations fund in the Bronx in response to the police violence that occurred on June 4 in Mott Haven.[D]

A Notice of Claim is an approximately two-page form used to notify the City of New York that someone intends to file a lawsuit against a city agency. It is a summary of the relevant facts and the person’s injuries but not an exhaustive account of the incident. Although we cannot offer formal diagnoses without ourselves interviewing and examining these individuals, their accounts describe events at the hands of the NYPD that meet the diagnostic criteria of “traumatic events” and subsequent symptoms consistent with depression, anxiety, and/or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These 23 protestors all describe experiencing physical, mental, and verbal abuse directed at them and witnessing these abuses against other people. Their accounts also depict trauma from perceived helplessness that they were unable to help – and were, in some cases, prevented from helping – other people in pain and distress.

There is a growing body of evidence that both experiencing and witnessing police violence are independently associated with poor mental health and sometimes poor physical health. Such police violence is collective and harms the communities in which it occurs. This injury is amplified in the United States’ predominantly Black and Brown communities in the United States that have disproportionately experienced and witnessed police violence across generations. Over-policing and violent events such as the NYPD response to the Mott Haven protest constitute collective traumas that have resulted in both individual and community harm. These wounds have additive and broad effects on community members and pose threats to community trust and cohesion, overall well-being, and social bonds.

A. Mott Haven and the Bronx

The Mott Haven-Port Morris neighborhood, where the protest and police response occurred on June 4, is located in the South Bronx. The Bronx county population consists primarily of Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black people, ranks last[E] for county health outcomes in the state of New York, and is home to the lowest-income congressional district in the country.[4] Residents of neighborhoods such as Mott Haven face significant institutional and structural barriers to their health and well-being.[F]

Mott Haven is patrolled by the NYPD’s 40th precinct. Among the 77 NYPD precincts, the 40th precinct has received the third highest number of civilian complaints about police misconduct and the most complaints for police use of physical force since 2015.[5] Under NYPD policy and New York State law, the decision to use force and the force itself must be “reasonable.”[6] Any application of force that is judged to be “unreasonable under the circumstances … will be deemed excessive and in violation of department policy.”[7] While the population of the Bronx constitutes 17 percent of the New York City population, 25 percent of police use of force incidents in 2019 were against its residents.[8]

The NYPD, particularly in the Bronx, has demonstrated a pattern of abuse, including “false arrests, warrantless searches, frequent use of strip searches, denial of medical attention, physical abuse, lewd conduct, and arrests without probable cause.”[9] The 40th precinct was among the most active precincts in the unlawful police practice of “stop and frisk.”[10]1 In 2013, a tape played in a Federal District Court revealed that Deputy Inspector Christopher McCormack, the commanding officer of the 40th precinct, pressured officers to conduct more street stops of young, Black men.[11],[12]

B. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19)

The Bronx has the highest number of COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations of the five New York boroughs, with people of color in the Bronx suffering the highest rates of severe illness and death.[13] As of January 2021, COVID-19 had infected one in 22 and killed one in 338 people of the Mott Haven community.[14]In contrast, about three miles south in the Upper East Side of Manhattan, COVID-19 had infected one in 50 and killed one in 1,427 people.[15] The county fatality rate for The Bronx is 6.78.[16] While every New Yorker has been affected by COVID-19, the inequitable impact on Black, Latinx, and low-income communities has been devastating and compounded by underinvestment in these communities.

C. June 4, 2020 Anti-police Violence Demonstration and Mass Arrests

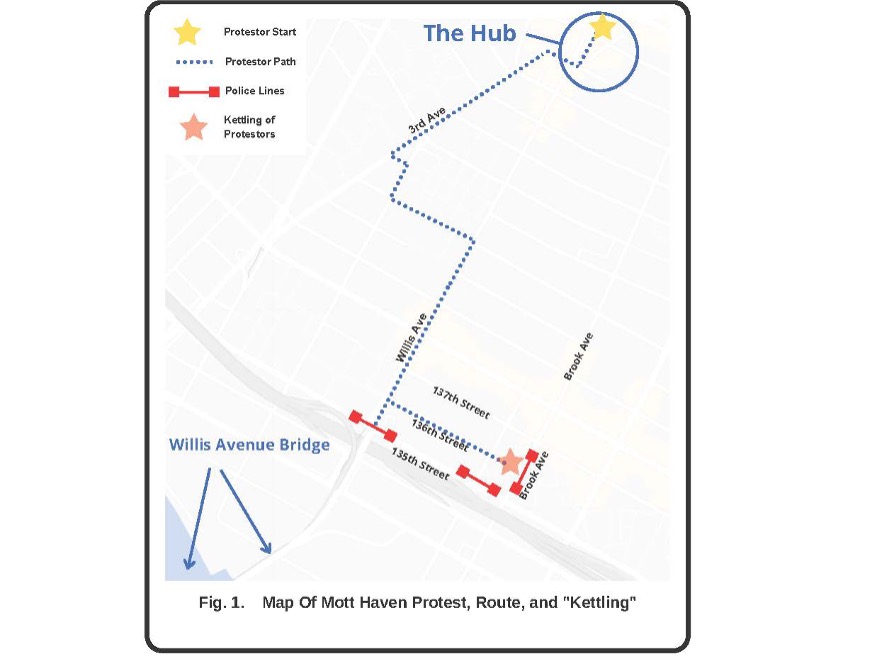

On the evening of June 4, 2020, a number of community-based grassroots organizations planned a demonstration to begin at The Hub, a retail area that lines the northern

border of Mott Haven and marks the convergence of East 149th Street and Willis, Melrose, and 3rd Avenues.[17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]

A Human Rights Watch (HRW) investigation detailed organizers’ flyers that stated a Code of Conduct[G] and specifically instructed demonstrators not to bring weapons. [25] That investigation determined that protest organizers had not planted weapons or posed any credible threat, contrary to what the NYPD reportedly told nearby businesses as they planned an elaborate response to the June 4 protest.

The event started with a mutual aid fair around 6:00 p.m., which included the distribution of food and medical supplies.[26] It was reported that there was already a heavy police presence at and around The Hub.[27]Around 7:00 p.m., approximately 300 people had gathered in preparation for a march through the community of Mott Haven. A curfew, implemented on June 2 and the first New York City curfew in 75 years, would take effect at 8:00 p.m.[28] [29] [30]

As the protestors marched toward the Willis Avenue Bridge, they were met at 135th street with a line of at least 50 police officers dressed in riot gear and with bicycles, blocking their path.[31] The protestors diverted to a side street, 136th street, and were met with more police officers in riot gear off Brown Plaza and Brook Avenue, locking them into place.[32] Reportedly, there were no announcements directing the protestors to leave and no directions given to the crowd. Multiple sources report that the crowd was then surrounded by police officials from all sides with nowhere to escape, a practice termed “kettling.” [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] The protestors were kettled before the 8:00 p.m. curfew and then physically prevented from dispersing.

By 8:10 p.m., the police officers began beating the crowd with batons, shoving, punching, and dragging people in the street, firing pepper balls, and firing pepper spray directly into protestors’ faces.[39] There were also accounts of acts of police violence against community members not directly involved in the protest.[40] As arrests were being made, some protestors were bleeding, and protestors’ hands were bound with zip ties, many so tightly that people reported that their hands went numb and turned blue; some were left with deep indentations and bruising.[41], [H]

Volunteer medics reported dangerous police violence and excessive force, such as jumping off cars into groups of people and striking with batons downward from cars, and that medics were prevented from tending to the injured.[42] The medics also reported being violently shoved, physically intimidated, and threatened.[43] These assaults injured[I] at least 61 protestors.[44] HRW investigators also found, from both video footage and interviews, that, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, many of the police officers were not wearing masks and even pulled masks off of protestors as they were being arrested. Protestors were kept in holding facilities for hours while offered no food and little or no water. Some were released late at night on June 4 or in the early hours of June 5, while others were held longer.[45]

The HRW investigation did not find any credible threats or acts of violence by the protest organizers or protestors during the protest in Mott Haven. They determined the protest was entirely peaceful.

The NYPD’s highest-ranking uniformed officer, Chief of Department Terence Monahan, led the violent operation in Mott Haven, despite taking a knee[J] with protestors a few days prior.[46] Monahan was also seen on camera at the Mott Haven protest and other protests without a face mask, despite face covering requirements at that time in New York City.[47]

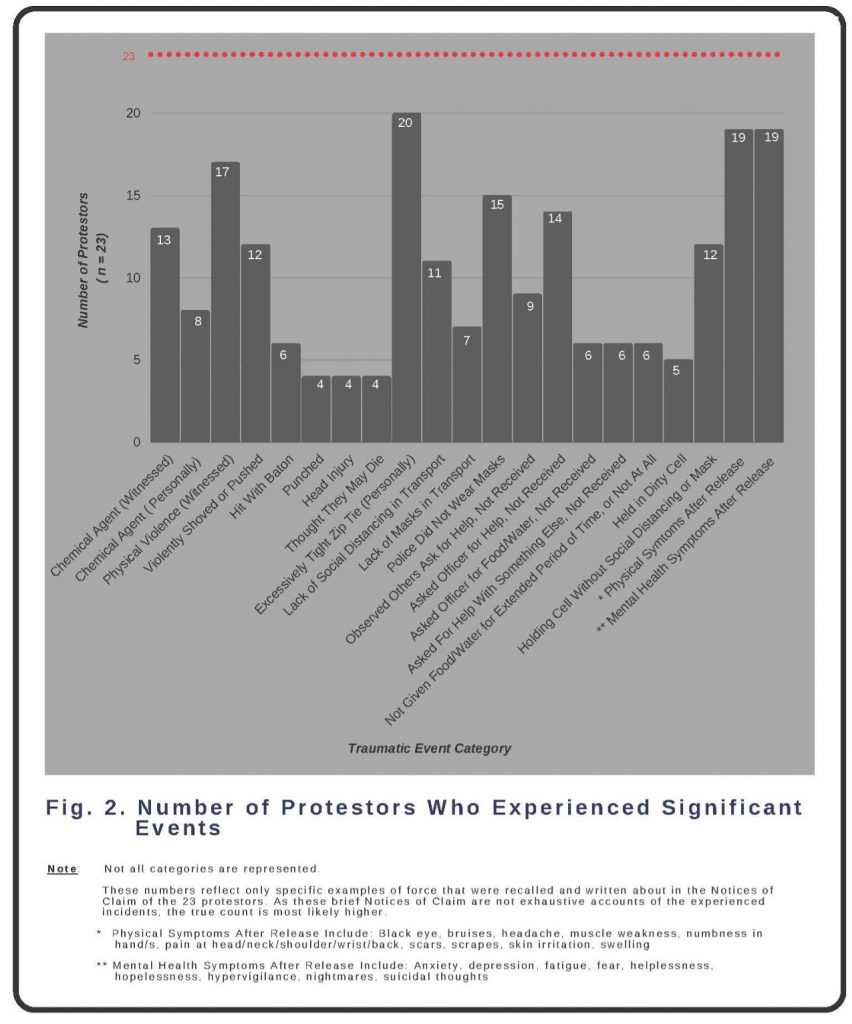

Section Two: Summary of Experiences of 23 Bronx Defenders’ Clients

As medical and mental health professionals with expertise in consequences of exposure to violence and other traumatic events, on behalf of Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), we reviewed the de-identified Notices of Claim of 23 protestors who had been arrested at the Mott Haven protest on June 4. We grouped the recounted experiences of the 23 people into 37 categories of experiences and then consolidated these into 27 categories[K]; examples of 21 pertinent consolidated categories are shown in Figure 2. These represent categories of force, trauma, and other adverse events that the 23 protestors experienced as a whole.

Of note, we only included people in each category if they specifically described experiencing that event or symptom in their Notices of Claim. Based on their statements, all 23 clients clearly experienced and witnessed traumatic events. However, unless a client’s statement specifically included descriptions of ongoing physical or mental health symptoms experienced after these exposures, we did not include that person in the count for that category. Thus, this methodology likely underestimates these individuals’ traumatic events and subsequent symptoms. More complete statements or interviews may have captured additional relevant information.

The mean age of the 23 protestors was 30 years old, with racial identities including Black, Latinx, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and White. Twenty-one protestors live in New York City, with six in the Bronx. All 23 protestors were arrested and taken to a processing center or jail, with 16 of them taken to a precinct outside of the Bronx. It is unclear why some received a summons and others received a Desk Appearance Ticket (DAT) for the same purported offenses.

According to their Notices of Claim, almost all described being kettled, witnessing and experiencing police use of force, either requesting or observing others requesting help from police and not reviewing it in a timely manner if at all, and suffering ongoing mental health symptoms and/or functional decline following the traumatic events they experienced at the Mott Haven protest. One protestor witnessed police preventing a volunteer medic from providing medical aid. Three people reported witnessing officer/s laughing at pain/symptoms/requests for assistance. Four people reported believing that they were going to die at the hands of police.

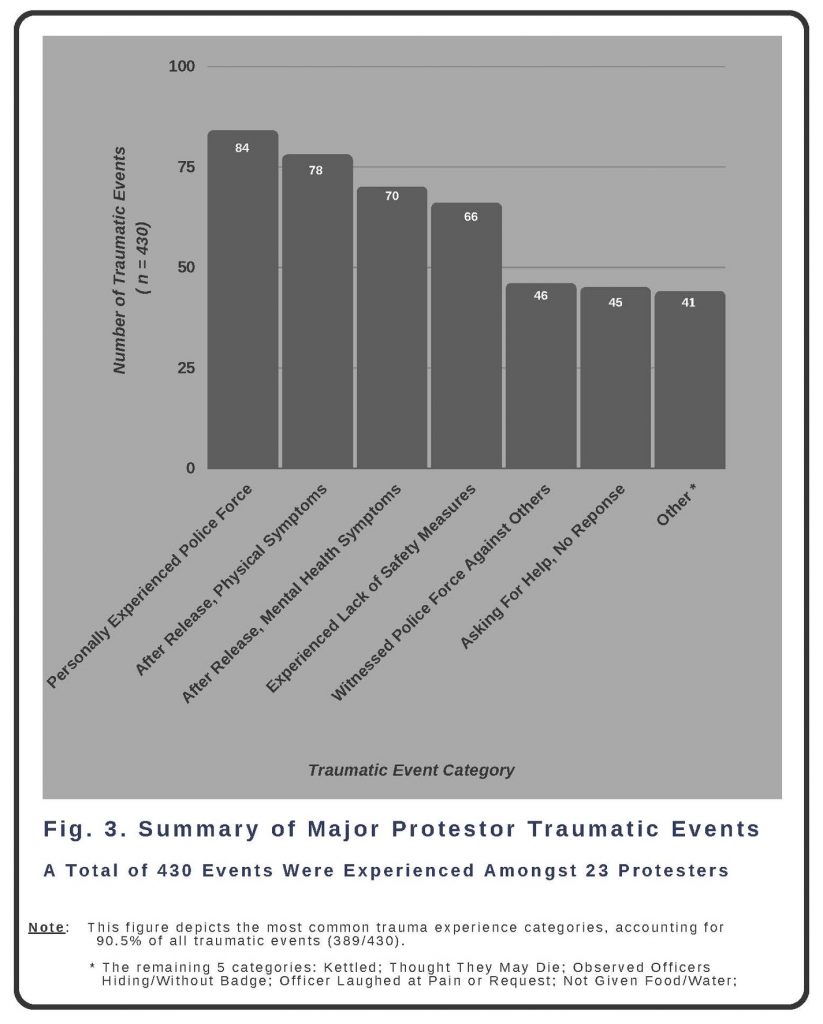

In addition to classifying numbers of protestors reporting each category of harm, we tabulated individual adverse experiences from the June 4 police response in an attempt to quantify the different forms of trauma or injury each individual protestor experienced. PHR experts counted 430 total potentially harmful experiences or events across the 23 protestors, resulting in an average of 18.7 experiences per protestor. The events were combined and nested within 11 umbrella categories:

1. Kettled;

2. Witnessed police force against others;

3. Personally experienced police force;

4. Reported fearing that they might die from police force;

5. Observed officers hiding or covering identification badges;

6. Experienced a lack of public health and safety measures;

7. Observed or experienced asking for help from the police with no response;

8. Reported officer/s laughing at their expression of pain/symptoms/request for assistance;

9. Not given food or water for an extended period of time or at all;

10. After release, reported ongoing physical symptoms; and

11. After release, reported ongoing mental health symptoms.

The vast majority (90.5 percent) of events fall into 6 of the 11 categories: witnessed police force against others; personally experienced police force; experienced a lack of public health and safety measures; observed or experienced asking for help from the police with no response; after release, reported ongoing physical symptoms; and, after release, reported ongoing mental health symptoms. These are defined and described in more depth below.

Personally Experienced Police Force (n = 84 events, ≈ 19.5 percent of total events)

This category includes the following experiences: personally getting pepper sprayed; excessively pushed or shoved (more than one push to the ground during arrest); grabbed or physically intimidated; hit with baton; punched; head injury (from being hit or slammed into something); personally had too tight zip ties/pain/injury from zip tie or arm position; being the direct target of verbal abuse/intimidation; and officer put a knee on their neck. Example incidents:

1. “Officer John Doe 2 … put his knee on Claimant’s neck… Claimant told the officers that he couldn’t breathe but John Doe 2 remained on his neck and the others [police] did not intervene.”

2. “… one officer … pushed claimant against a fence and attempted to cuff claimant. Claimant complied and put his hands behind his back; however [the officer] began to hit claimant’s right side with a baton.”

3. “The claimant was kicked in the head by officer B.”

After Release Reported Ongoing Physical Symptoms (n = 78 events, ≈ 18 percent of total events)

Physical symptoms were tallied as one count per symptom per body part. Plural body parts were assigned two counts unless a specific number was assigned (for example: “fingers” versus “three fingers”). Physical symptoms included: black eye; bruises; headache; muscle weakness; numbness in hand/s; pain at head/neck/shoulder/wrist/back; and scars, scrapes, skin irritation, and swelling. Examples:

- “… two months later the claimant continues to experience numbness in her right hand.”

2. “… welts on his inner wrists … required wearing a [wrist] brace, limited mobility … shooting pains … nerve damage to some of his fingers and inner wrists.”

3. “… eye blackened for at least 2 weeks … pain in her eye for a month.”

After Release Reported Ongoing Mental Health Symptoms (n = 70 events, ≈ 16.5 percent of total events)

Ongoing mental health symptoms and emotional trauma included: feeling anxious; feeling depressed; fatigue; fear of police; fear of loud noises; feeling unsafe; helplessness; hopelessness; hypervigilance; insomnia; nightmares; and suicidal thoughts. Examples:

1. “… hypervigilance, intrusive images of violence, triggered by seeing the police.”

2. “… suicidal thoughts …”

3. “… fear of police, fear of loud noise, fear of going somewhere alone …”

Experienced a Lack of Public Health or Safety Measures (n = 66 events, ≈ 15 percent of total events)

The category of events or experiences that broke public health and/or safety laws/recommendations included: transported without social distancing; transported without masks; not given seatbelt during transport; detained in a crowded cell without social distancing; detained in a crowded cell with others not wearing masks; observing that police did not wear masks; and police prevented medical aid.

1. “Officer Jamie Doe 3 … told the claimant and others in line … there was no need for social distancing and the novel coronavirus did not exist.”

2. “The bus claimant was transported on had dried blood on the ceiling. There were many protestors on the bus that were bleeding …”

3. “… [the] holding cell was unsanitary, with no running water, feces covering the walls and cockroaches crossing the cell’s floor…”

4. “While driving, Officer Jamie Doe 16 drove in the rain through a red light without his sirens on and laughed, looked back at the claimant and told the claimant he ‘would have made a ton of money’ if any collision had occurred and the claimant had survived.”

Witnessed Police Force Against Others (n = 46 events, ≈ 11 percent of total events)

The category of directly witnessing police force against other human beings included: witnessing delivery of pepper spray or pepper balls; witnessing force (defined as watching police hitting with a baton, shoving to the ground, or grabbing or using their body or police shield to physically intimidate a protestor); and observing zip ties that were too tight (hearing verbal cries, or seeing swollen, blue, or bleeding hands). It is important to note that “witnessing force” was counted based on the experience[L] and not the number of people who received the police force. For example, if a protestor witnessed a police officer hitting a group of people and shoving three people to the ground, this counted as two experiences (hitting, shoving to ground). If a protestor witnessed five police officers hitting people with their batons for two hours, this counted as one experience (hitting with batons). Therefore, the 46 events are an underestimate.

1. “Claimant saw his friend … hit over the head by a police officer with a baton…”

2. “… witnessed … [people being] pepper sprayed directly in their eyes, hit by batons, punched in their stomachs, had their head sliced open, and/or bodies dragged against the pavement…”

3. “… witnessed … [a police officer] … grab a Black woman by the neck. Two more white officers … hit her in the chest and face.”

Observed or Experienced Asking for Help from Police with No Assistance Provided (n = 45 events, ≈ 10.5 percent of total events)

The category of events or experiences of needing or asking for help that was ignored included: observing others ask for help and not receive it; personally asking an officer for help due to pain or a medical issue and not receiving it; personally asking an officer for food or water and not receiving it; and personally asking for help for something else and not receiving it.

1. “A young man whose wrists were also zip-tied told the officers he was experiencing numbness and pain in his hands…. Another protester said she was an emergency room doctor and pleaded with the officers to replace the young man’s zip ties, the officers refused to do so.”

2. “Officer Jamie Doe 6 … provided 1/2 gallon of water to be shared among the [other people in the holding cell] … upon complaint, Officer Jamie Doe 6 threatened to withhold the 1/2 gallon [of water].…”

3. “... crying out for medical treatment, including a man appearing to be in his 50s who was suffering tremendously … [and] a woman who appeared to be suffering from a seizure, but the police officers ignored the multiple requests for medical assistance.”

The way these experiences were counted minimizes the actual and cumulative effect of what people experienced in Mott Haven on June 4. These numbers reflect only specific examples of potential harms that were recalled and written in the Notices of Claim that we reviewed. Given the nature of trauma and the fact that Notices of Claim are not exhaustive accounts of the incident, we believe the true count to be higher. Protesters were trapped by police, stripped of their freedom of speech, experienced chemical and kinetic impact weapons, experienced physical injuries – including being beaten – which resulted in blood pooling in the street, experienced deliberate indifference to calls for help and medical attention, were denied food and water, were denied a bathroom, and were held in unsanitary and crowded conditions in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic that had already taken an extraordinary proportion of lives in their community.

Research from throughout the world over several decades documents how these types of physical and emotional traumas impact individuals and communities and can manifest as long-term psychological and physical conditions that impair health and well-being. Research and evidence on individual effects are explored in the next section.

Section Three: Individual Mental Health Harms from Protest-Related Police Violence and Mistreatment

People exposed to stressful or traumatic events, such as the events in Mott Haven on June 4, 2020, may experience a range of harmful individual mental health consequences. Within its diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder, the American Psychiatric Association’s most recent edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) employs a strict definition of what constitutes a traumatic event.[48] It is defined as an exposure to “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence in one (or more) of the following ways: 1. directly experiencing the traumatic event(s); 2. witnessing, in person, the event(s) as it occurred to others; 3. learning that the traumatic event(s) occurred to a close family member or close friend. (In cases of actual or threatened death of a family member or friend, the event(s) must have been violent or accidental); 4. experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s).”

By these criteria, the protestors present at the Mott Haven protest – and specifically by the 23 people whose Notices of Claim we reviewed and whose experiences are summarized in Section Two – meet the definition of having had exposures to traumatic events created by the reported actions of the NYPD. As delineated in Section Two, all 23 protestors were subject to the threat of serious injury, with several explicitly expressing their fear of being killed by police. Twenty-two of the protestors themselves described experiencing direct violence against them, totaling 84 events.[M]

These traumatic exposures to violence and the threat of violence were likely exacerbated by the additional additional threat of the police officers forcibly preventing the arrested protestors from observing recommended safety measures (wearing a mask, avoiding immediate physical proximity to other unmasked people) in the midst of a pandemic caused by highly contagious and deadly virus. Further, the trauma inflicted by state actors such as police officers is potentially even more damaging as the violence is perpetrated by people in positions of authority and essentially inescapable.

We are not able to provide formal mental health diagnoses of the 23 people whose Notices of Claim we reviewed without conducting formal interviews and clinical assessments of each individual ourselves. However, the individuals’ statements in their Notices of Claim are supported by a large and growing body of evidence on the principal mental health diagnoses and symptoms most prevalent after exposure to the type of police violence and mistreatment that these people experienced. Witnessing and directly experiencing police violence exposure are each associated with a broad range of adverse physical health and mental health outcomes.

The most common psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses resulting from police violence and mistreatment are those of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), as well as other manifestations of psychological distress. Police violence in the literature encompasses acute events of physical, sexual, psychological, or neglectful violence, as per the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidelines for defining violence.[49] The WHO defines violence as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation.”[50]

A. Definitions

1. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

PTSD is characterized by the development of characteristic symptoms following exposure to a traumatic or stressful event as defined above (Criterion A). To be formally diagnosed with PTSD, a person must re-experience the trauma in at least one of the following ways: unwanted upsetting memories; nightmares; flashbacks; emotional distress after exposure to traumatic reminders; or physical reactivity after exposure to traumatic reminders (Criterion B). One must avoid trauma-related thoughts, feelings, and/or reminders after the trauma (Criterion C). The traumatic event must have induced or worsened at least two of the following negative thoughts or feelings: inability to recall key features of the trauma; overly negative thoughts and assumptions about oneself or the world; exaggerated blame of self or others for causing the trauma; negative affect; decreased interest in activities; feeling isolated; and difficulty experiencing positive affect (Criterion D). Moreover, the exposure must have induced or worsened trauma-related arousal and reactivity manifested by at least two of the following: irritability or aggression; risky or destructive behavior; hypervigilance; heightened startle reaction; difficulty concentrating; or difficulty sleeping (Criterion E). Symptoms must last for more than one month, create distress or functional impairment, and not be due to medication, substance abuse, or other illness. People with Acute Stress Disorder have these symptoms of PTSD after a traumatic event, though of shorter duration.

Even if people do not experience all of the debilitating symptoms to meet diagnostic criteria for a formal diagnosis of PTSD, each of its constituent symptoms can lead to significant psychological distress and impairment.

2. Depression

According to the DSM-5, one must experience one of two main criteria for a diagnosis of depression: 1) depressed mood (sadness or negative emotions); and/or 2) anhedonia (lack of pleasure or interest in things you once enjoyed). Secondary symptoms may include somatic symptoms such as sleep difficulties (too little or too much), changes in appetite or weight, poor concentration, fatigue, and psychomotor agitation or delay. They may also include feelings of worthlessness or guilt, and thoughts of suicide or death.

3. Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

The DSM-5 defines Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) as experiencing excessive anxiety and worry that is experienced as challenging to control and without a specific threat present or in a manner disproportionate to actual risk about a variety of topics, events, or activities over at least six months. The anxiety is accompanied by at least three of the following physical or cognitive symptoms: edginess or restlessness; tiring easily, feeling more fatigued than usual; impaired concentration or feeling as though the mind goes blank; irritability; increased muscle aches or soreness; and difficulty sleeping. The anxiety, worry, and other associated symptoms may make it difficult to carry out day-to-day activities and responsibilities and may cause problems in relationships, at work, or in other important areas of life. The symptoms must be unrelated to any other medical conditions and cannot be explained by a different mental disorder, or by the effect of substance use, including prescription medication, alcohol, or recreational drugs.

4. Psychological Distress

While psychological distress is not a specific diagnosis, it is defined as a set of painful mental and physical symptoms that may be associated with normal fluctuations of mood or may indicate the beginning of major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, PTSD, or other clinical condition. If prolonged, it can result in many of the disruptions to daily living associated with mental health diagnoses, such as GAD, PTSD, and depression.32[51]

Of note, living in conditions of economic hardship and a context of structural racism in and of itself increases vulnerability to PTSD, anxiety, and depression, so additional traumatic experiences are even more likely to result in psychopathology. It is also worth noting that people already living in difficult socio-economic conditions with little room for error can be tremendously impacted by missing even one or two days of work. Even brief impairments that may not meet the duration requirement for a formal mental illness diagnosis could still have negative implications for the individual and their family.

B. Evidence on Individual Mental Health Effects from Experiencing or Witnessing Police Violence and Mistreatment

People who are exposed to traumatic events are at elevated risk for multiple mental health symptoms compared to those with no traumatic exposures. Both the severity of risk and the type of exposure matter. A growing body of research suggests that the “police” in “police violence” may bestow a specific heightened meaning that extends beyond the violence and threats of violence itself. Researchers such as De Vylder et al. have enumerated distinct and pernicious features of police violence that may contribute to especially harmful effects on the mental health of its victims.[52] These include:

- Police officers are in positions of state-sanctioned power. In interactions with civilians, police officers are in positions of greater power because of both the symbolic and state-sanctioned status of their profession and their legal possession of the means (e.g., guns, batons, tasers) to wield force, threat of force, and coercion at their discretion.[53]

- The police are a pervasive presence. A core characteristic of many people’s reaction to violence is avoidance of reminders and triggers – especially of the perpetrators themselves. But this coping mechanism is not available to people exposed to police violence, as the presence of law enforcement officers in the United States is pervasive in public places.

- There are limited options for recourse. Victims of police violence have little legal recourse or opportunities for seeking help in the criminal legal system. Too often egregious behavior is allowed, without consequence or policy change.

- Police culture deters internal accountability. This creates a climate of perceived impunity and a perception of hopelessness among victims that wrongs will be redressed.

- Police are supposed to uphold the law. The police represent a societal institution that some have come to rely on for help when a threat emerges. When police perpetrate violence, this belief is shattered, as the police are no longer protectors but rather the central threat that needs to be addressed.

- There are racial and economic disparities in exposure. Police violence in the United States is disproportionately directed toward people of color, namely Black people and people in low-income communities. These disparities uphold structural and institutionalized racism and classism. [54]

C. Evidence on Effect on Individuals of Negative Interactions with Police

Cross-sectional studies have consistently found clinically and statistically significant associations between a person’s exposure to police violence or ill treatment and a range of mental health outcomes.[55] Many studies show adverse mental health effects from police treatment far less physically violent than that experienced by the Mott Haven protest. For example, community-level data has demonstrated higher rates of mental health symptoms in neighborhoods or cities in which aggressive policing (e.g., “stop and frisk” practices primarily used in neighborhoods predominantly composed of people of color) are more common.[56] A 2014 population-based survey of 1261 young men in New York City found that men who reported unwanted police contact through “stop and frisk” tactics reported more symptoms of PTSD and anxiety than those with fewer police contacts, even after adjusting for demographic characteristics and prior arrests.[57]

Anxiety symptoms were significantly related to the number of times young men had been stopped and to how they perceived the police to conduct the encounter.[58] Young men who reported fair treatment in these encounters reported fewer PTSD symptoms, and both PTSD and anxiety symptoms increased with reported worse treatment during police stops. More lifetime stops were associated with more trauma symptoms, with trauma levels significantly higher among public housing residents.[59]

In a 2020 systematic review, six of 11 studies demonstrated a nearly twofold higher prevalence of mental health symptoms (PTSD, depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation and attempts, and psychological distress) among Black people who reported a prior negative interaction with police compared to those with no interaction.[60] These associations have generally been found to remain statistically significant (and of sufficient effect sizes to support public health significance) even with adjustment for other forms of violence exposure, such as interpersonal violence or lifetime abuse exposure. A 2018 cross-sectional survey of adults living in U.S. urban areas found that respondents who reported negative experiences with the police, even if they perceived these encounters to be necessary, had higher levels of medical mistrust compared to those with no negative police encounters. Such mistrust in turn can contribute to not seeking health care in the face of medical needs, worsening health outcomes.[61]

In a 2017 population-level study, 1615 residents in Washington, DC, New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia completed well-validated measures of psychological distress (K-6 scale), depression (PHQ-9) and prior experiences of police victimization based on WHO domains of violence. These included physical violence (with and without a weapon), sexual violence (inappropriate sexual contact, including public strip searches), psychological violence (e.g., threatening, intimidating, stopping without cause, or using discriminatory slurs), and neglect (police not responding when called or responding too late). Some 18.6 percent reported psychological violence, and 18.8 percent reported police neglect; 6.1 percent reported physical violence, with 3.3 percent reporting physical violence with a weapon. Nearly all forms of victimization were associated with psychological distress and depression after adjusting for possible confounders.[62] An increased prevalence of police encounters is not only linked to elevated stress and anxiety levels, but also with increased rates of high blood pressure, diabetes, and asthma – and fatal complications of those comorbid conditions.[63]

D. Evidence on Effects on Mental Health of Witnessing Violence

Multiple studies have shown that witnessing violence is associated not only with PTSD but also with other mood and anxiety disorders. One nationally representative study in South Africa found that those who reported witnessing violence were 50 percent more likely to develop a mood or anxiety disorder compared to those who did not report witnessing violence.[64] This effect remained even after adjusting for a prior PTSD diagnosis. The researchers further found that people who witnessed violence were not only significantly more likely to develop mood and anxiety disorders, but also developed the disorders significantly earlier than those who did not report witnessing violence.

A 2020 systematic review of 52 studies (n = 57,487 participants) from 20 countries/regions examined mental health outcomes directly or indirectly influenced by an identified collective action such as a protest.[65] In this review, the prevalence of PTSD ranged from 4 percent to 41 percent in communities in which there had been a protest with violence. Following a major protest, the prevalence of probable major depression increased by 7 percent, regardless of personal involvement in the protests, suggestive of community spillover effects. This systematic review found that the negative impact of exposure varied with the level of violence. Proximity to violence was an important predictor for depression.

A particularly debilitating symptom of PTSD is hypervigilance, the feeling of being constantly on guard so as to detect potential danger, even when the risk of danger is low.[66] A 2020 study of adults in Chicago found that exposure to police violence was associated with a 9.8-percentage-point increase in a well-validated hypervigilance score (on a 100-point scale), nearly twice that associated with exposure to community violence (a 5.5-percentage-point increase).[67]Among participants who reported having had a police stop, experiencing the stop as a traumatic event (defined as an exposure to actual or threatened death or serious injury) was associated with a 20.0-percentage-point increase in the hypervigilance score. Scoring in the highest quartile of hypervigilance was associated with higher systolic blood pressure (an increase of 8.6 mmHg).

E. Evidence on Effects on Individual Mental Health of Exposure to Police Violence in Protests

There is a growing body of research focusing specifically on the mental health effects of exposure to police violence during protests. A 2020 survey of 523 adults who had participated in the Yellow Vest protests in France examined links between being exposed to police violence and depressive and PTSD symptoms. They found that 49 percent of the protestors reported symptoms of severe depression and 15.5 percent met diagnostic criteria for PTSD, with exposure to police violence strongly associated with reporting these symptoms, after adjusting for multiple potential confounders such as physical injuries, demographics, and political views.[68]

A 2016 study examining the mental health effects of exposure to police violence during the August 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri found high rates of PTSD symptoms, depression, and anger among those exposed to violence during the protests.[69] The amount of fear one experienced secondary to exposure to violence emerged as the strongest correlate of psychological distress, not only for PTSD, but also for depression and anger. Black community members reported more symptoms of PTSD and depression than White community members.

Most studies on prevalence of PTSD after witnessing or experiencing police violence are cross-sectional, so the incidence and course of PTSD following these exposures remain unknown. To date, prevalence of PTSD drawn from probability samples has ranged from an estimate of 4.1 percent of subjects six to eight months after the 1992 Los Angeles uprisings to 41 percent of residents in affected areas seven to nine months after ethnoreligious riots in Jos, Nigeria.[70],[71] Experiencing violence was most consistently associated with increased risk of PTSD. Witnessing a personal attack and being in close proximity to violence have also been associated with PTSD risk.[72]

F. Evidence on Effects on Individual Mental Health of Being Stopped and Arrested by Police

Being arrested and detained by police, even without being incarcerated, is associated with poor health outcomes. For instance, those on probation have a higher age-standardized mortality rate than does the general population.[73] Exposure to the criminal legal system has been found to impair individuals’ overall well-being, defined as a person’s overall condition, encompassing physical health as well as emotional, social, and spiritual components, even when multiple other factors influencing well-being are taken into account. Well-being is a critically important indicator of individual and population-level social welfare. Validated measures of well-being based on self-reported life evaluation are also strongly associated with key indicators of population health, such as life expectancy. In a nationally representative study, each of three types of criminal legal system exposure – being stopped and searched by police, being arrested, and being incarcerated – were associated with lower proportions of thriving in overall life evaluation and in every domain of well-being.[74] The negative association between exposure to police stops with searches and odds of a thriving life evaluation was similar in magnitude to the association estimated for those who experienced multiple incarcerations. This illustrates the extent to which even lower-level contact with the criminal legal system is negatively associated with quality of life. These associations between police contact and well-being persisted in sensitivity analyses that excluded formerly incarcerated people, suggesting that this association is driven by factors independent of incarceration.

G. Mental Health Symptoms Reported in Notices of Claim of 23 Mott Haven Protestors

This body of evidence provides important context for the symptoms described in the Notices of Claim of the 23 protestors we reviewed. Nineteen claimants describe experiencing cardinal symptoms of PTSD, depression, or anxiety since the events at the Mott Haven protest, with some describing symptoms consistent with all of these conditions.

Symptoms of PTSD

We do not know how the 23 protestors are doing since providing the Notices of Claim we reviewed, or how long their symptoms have lasted. Without including diagnostic time requirements, 11 of the 19 protestors describing mental health sequelae described symptoms consistent with PTSD. They described experiencing unwanted upsetting memories; nightmares; flashbacks; emotional distress after exposure to traumatic reminders; or physical reactivity after exposure to traumatic reminders (Criterion B). Additionally, claimants described experiencing the following: “triggering when sees police or hears police sirens”; “triggering when sees location of incident”; “recurring and intrusive images of violence”; “flashbacks induced by certain triggers”; “nightmares”; and “night terrors.”

These symptoms can cause severe impairment and lead those who experience them to resist going to sleep for fear of having nightmares or to have difficulty falling asleep because their bodies are constantly on edge, creating a cycle of sleep deprivation. This loss of vital rest contributes to worse daytime functional impairment and distress. Moreover, fear of being exposed to traumatic reminders (e.g., hearing police sirens, being near site of trauma), discussed below under Criterion C, can lead to severe restriction of activities, agoraphobia (fear of being in situations where escape might be difficult), social isolation, and inability to meet daily responsibilities, such as traveling to and engaging in work or school, or even family life.

Claimants described avoiding trauma-related thoughts, feelings, and/or reminders after the trauma (Criterion C). Examples of statements from the claimant Notices of Claim that exemplify Criterion C include: “avoidance of activities that could result in a law enforcement encounter”; “fear of seeing police, loud noises, sirens, going places alone”; “daily recurring thoughts about what happened.”

Claimants further described experiencing negative thoughts about the world and increased negative affect (Criterion D).

And claimants described trauma-related arousal and reactivity manifested by hypervigilance, heightened startle reactions, difficulty concentrating, and/or difficulty sleeping (Criterion E). Examples of these include: “feeling unsafe even in his own home”; “experiencing an omnipresent sense of hyper-vigilance”; “racing thoughts about the experience that prevent him from staying focused during the day and cause him trouble sleeping at night”; and “fear of going outside.”

Each of the symptoms associated with PTSD can be highly disruptive and deleterious. They can undermine an individual’s well-being, daily function, and community interactions. Even everyday situations like walking down the street can become a source of significant stress and anxiety, as people feel a continual sense of potential danger. These symptoms are especially severe when the danger is associated with the police and when individuals live in highly policed communities. Over time, the cumulative effects of hyper-reactivity, negative affect, insomnia, and restriction of activities can lead not just to mental but also to physical health consequences. Further, these symptoms may cause the loss of livelihoods and supportive social relationships.

Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety

All 19 of the claimants relating mental health sequelae described symptoms consistent with depression and anxiety. These include descriptions of “feeling depressed,” having “high levels of anxiety,” and “having panic attacks.” Other descriptions consistent with symptoms of depression and anxiety from the claimant Notices of Claim include: “having insomnia”; “trouble sleeping”; “low mood”; “a sense of helplessness”; “suicidal thoughts”; “feeling broken emotionally”; “diminished energy” as well as “feeling overwhelmed since release from detention.”

Again, each of these symptoms creates significant individual psychological distress that also makes even routine daily activities difficult, and may lead to social withdrawal, impaired capacity to engage in work and educational activities, and overall diminished ability to meet responsibilities.

Physical Symptoms

We are unable to fully assess physical sequelae to the harms experienced by the 23 claimants without conducting in-depth histories and physical examinations. It is of note, however, that 19 of the 23 claimants reported physical symptoms after their release from police custody. Some protestors had ongoing symptoms at the time of their Notices of Claims. These included joint pains, shooting pains to their hands from possible nerve damage, numbness in the hands, body pain, concussion, skin lesions, and scarring.

H. Community Trauma

The effects of exposure to a violent event often are not limited to a specific incident. Instead, they must be considered within the larger context in which the incident occurred. The concept of continuous traumatic stress can be applied to situations in which the threat of police violence is pervasive and recurrent. It has been identified as a contributor to compromised mental health and functioning, with negative effects not just on individuals but on social relationships and networks throughout a community. Police response to the Mott Haven protest was a shared traumatic event experienced by an entire community comprising different subgroups, each of which may have been influenced differently by a host of contextual variables. This is explored in more depth in the next section.

Section Four: Evidence on Community Trauma

What is community trauma? What creates community trauma?

Community trauma may be defined as the shared injuries to a community’s social, cultural and physical ecologies. It is a type of “collective trauma,” a term first coined by the sociologist Kai Erikson, who researched communities in the United States that had survived natural disasters. He distinguished community trauma from the experience of individual trauma. Erikson defined the effect of a traumatic exposure to an individual as:

“a blow to the psyche that breaks through one’s defenses so suddenly and with such brutal force that one cannot react to it effectively. [It constitutes] a deep shock as a result of their exposure to death and devastation, and, as so often happens in catastrophes of this magnitude, they withdraw into themselves, feeling numbed, afraid, vulnerable, and very alone.” [75]

In addition to these individual effects, Erikson definedcollective trauma as:

“a blow to the basic tissues of social life that damages the bonds attaching people together and impairs the prevailing sense of communality. It is a gradual realization that the community no longer exists as an effective source of support and that an important part of the self has disappeared.”[76]

Collective trauma thus undermines people’s basic sense of belonging, creating a deep sense of insecurity and lack of safety.

The concept of community trauma is important in helping broaden the understanding of the effects of trauma beyond just the effects on the individual of a singular highly stressful event.

Community or collective trauma is more than the sum of the experiences of individuals who have been exposed to highly stressful events. The disruption of relationships in a group (e.g., family, neighborhood, community, organizations) from trauma often causes high levels of distress and mental health difficulties well beyond the individuals directly exposed to the triggering events. This traumatic stress response at the collective level can take place without individuals themselves having symptoms of PTSD. [77]

Community trauma places these disruptive events in a larger context – one in which trauma is understood as an existential response that carries with it a community’s particular ways of coping with multiple traumatic events. Historical trauma may be transmitted intergenerationally, coded within the body, while over time losing its meaningful connection to context. In the context of the United States, for example, experts like Resmaa Menakem (2017) argue that contextualizing personal and embodied experiences of pain and distress and recovering their historical meanings are necessary for Black people to find pathways to healing from racialized trauma.[78] Across cultures, there is a diversity of ways that communities reckon with recent and/or historical traumatic events as attempts to move past collective traumatic events.

Collective traumatic events such as the police violence in Mott Haven in June 2020 often initiate a process by which a community asks, “What happened? How did this happen? Why did this happen? What do we need to do as a community to restore what has been disrupted? What do we need to do prevent what has happened to us in the future?” This collective process of narration may emphasize spiritual, moral, political, or scientific explanations and responses. For instance, following the terrorist attacks of 9/11, communities around New York City came together in spontaneous vigils to ask such questions and seek shared meaningful responses, with symbolic recognition of this shared trauma reflected in the creation of the 9/11 memorial.[79]

Viewing what happened in Mott Haven on June 4 through a collective trauma lens is particularly important because a primarily individual approach to trauma tends to locate trauma in the psyche of the person. It thus fails to address the destruction of human connections by organized physical and structural violence.[80] In locating trauma also in the relationships within families, kinship, and communities – and between communities and institutions like the police – we can take a systemic perspective on the ways in which traumatic events impact all levels of human systems, from bodies to psyches, social groups and institutions, to cultural and physical environmental ecologies.[81]This systemic perspective is a critical first step in designing the needed systemic interventions and remedies.

The collective trauma following police violence such as occurred at the Mott Haven protests in June 2020 must be considered in this context. The excessive use of force and mistreatment of the protestors will further exacerbate the Mott Haven community’s legitimate distrust and fear of the police. As the NYC Department of Investigation report on the NYPD Response to the George Floyd Protests noted:

“… public trust is at a low ebb, hampering the ability of the police to do their jobs. A perception that the police operate with impunity damages the morale of the vast majority of good and dedicated police officers, makes recruiting a diverse police force more challenging, and makes the NYPD’s core crime-fighting mission more difficult. While NYPD leadership may believe in good faith that they can effectively monitor themselves, we urge them to accept that in this moment their own efforts are not enough to restore and preserve trust with the public, and to seek a true partnership with robust civilian oversight.”[82]

Some of the most serious effects of community trauma are the tensions that develop within communities. In the case of the Bronx’s Mott Haven community, a history of police violence is coupled with the harm cause by the systemic under-investment of resources. This pairing simultaneously creates increased need of assistance and decreased access to it. There may be trauma reactions on both an individual and collective level in the form of increased mental health sequelae, including, but not limited to, PTSD. Further, these reactions are exacerbated by community residents’ increased vulnerability to trauma and stress due to lack of access to financial, nutritional, educational, and other resources.

Community Impact of Police Violence

Police violence not only directly harms the physical and mental health of individuals, it also harms families and communities by contributing to a climate of fear, chronic stress, and lowered resistance to diseases, even among those not directly harmed by police. For example, a 2018 population-based study found that 38,993 of 103,710 Black respondents were exposed to one or more police killings of unarmed Black people in their state of residence in the three months prior to the survey. Each additional police killing of an unarmed Black person was associated with significantly more additional poor mental health days among these respondents.[83]

The severity of traumatic symptoms may be difficult to understand if one examines only isolated incidents of police brutality.[84] We need also to look at intergenerational or historical trauma in order to analyze the antecedents and consequences of police brutality. Predominantly Black and Brown communities in the United States have historically experienced state-sponsored violence perpetrated against them, including through the trans-Atlantic slave trade, internment, abusive detainment, sexual assault, murder, brutality, family separation, forced assimilation, denial of rights and resource access, and mass incarceration.[85] [86] [87]As Bryant-Davis et al note, “Historical traumas that were legally supported and carried out by governmental agents such as police officers, have had lasting impact on the direct victims and their descendants.”[88]

Collective trauma on predominantly Black and Brown communities that have historically suffered from experiencing and witnessing police violence compounds on itself when it is experienced constantly. And thus, the violence on June 4 in Mott Haven can be expected to have an even larger impact on the community because it is just one event in a long history of over-policing and police abuse in the Bronx.

The use of force by police to suppress political opposition also creates traumatic effects reaching far beyond its individual victims. This violence toward communities demonstrates the risks of engaging in protest and may be intended or seen to be intended to discourage citizens from exercising their constitutional right to free speech. From the police abuses in apartheid-era South Africa, to crimes committed by forces under the control of the military juntas in Chile and Argentina, to the ongoing police abuses taking place in Brazil and the Philippines, there is ample evidence of such government actions contributing to community trauma.[89]

Community trauma is further exacerbated in its aftermath when its reality is denied by the government, and any efforts to bear witness to what happened are suppressed. Often referred to as the “trauma after the trauma,” the silencing leaves victims unable to have their experience acknowledged by society. Without acknowledgement, their chances of receiving material and social support are diminished. Not only are they harmed by direct violence but also by their reality of their abuse being invisible, unacknowledged, or denied. The tendency toward silencing the traumatic experience is often aided by the survivors and the public not speaking about past traumatic experiences, referred to as the “conspiracy of silence.” The survivors’ shame of being victimized and the public’s guilt and fear of harming the survivor by having them speak about their painful experiences often lead to this avoidance of communication.

The extent to which a population will continue to be affected by collective trauma is in part a consequence of what responses, if any, follow the violence. Without adequate acknowledgment of the seriousness of police violence, the community’s distress is perpetuated by the perceived inevitability of continued police abuse. This chronic stress is compounded by the lack of an appropriate response to the seriousness of the abuse and may contribute to the eventual occurrence of mental health difficulties. Monetary compensation alone for harms to individuals abused by the police, while important, does not constitute a reparative process on the community level. Compensation in and of itself is never satisfactory in such situations. There must also be a serious symbolic and structural dimension for communal redress to be effective. One of the most severe threats undermining the reparative process is impunity – the failure of the city or police department to acknowledge the seriousness of the violence, let alone hold those responsible accountable. The recommendations in Section Five further address why impunity undermines both the victims’ and the community’s process of healing.

Section Five: Responses to Individual and Collective Harms

The harms sustained by both individual protestors and the broader Mott Haven community require both individual and systemic responses. There needs to be redress for the individual protestors. There also must be measures to address the community spillover effects in the surrounding community. People who did not take part in the protest may experience psychiatric sequelae from the police actions on June 4, 2020 and the subsequent damage to intra-community and community-government relations. Interventions aimed at reducing the burden of trauma and its outcomes must include bystanders and other observers and not just those directly affected. Effective responses must also directly address collective trauma.

What actions should government take to address collective trauma?

There are a few different ways to approach this question. First, what would the community favor as an adequate compensatory process – and how does a community come to some consensus about what would be satisfactory? There is a body of research on how communities around the world reach such a consensus on addressing damage from political violence, and there are different trends in the kinds of compensations different communities favor, whether compensation is financial, symbolic, or consists of measures to promote systemic change and/or the prevention of future violence.53 How might the stakeholders and residents of Mott Haven be actively involved in a process to arrive at adequate reparative measures? Such processes of imagining preferred futures for the community may serve as an important tool for building community.

Many compensatory efforts initially focus on care for direct victims and their families as well as addressing deficits created by long-term under-investment in the community. Some of the initial methods of compensation may focus directly on building historically underfunded services (social services, health, and education). The movement to shift resources to other needed services in the community may be the most direct way of addressing such communal deficits. At the same time, it is important to build on and strengthen already existing capacities and community assets. As we have seen in many global humanitarian programs, exclusively focusing on addressing deficits often ignores and may even undermine existing capacities that need to be supported and strengthened. These capacities include community volunteerism and mutual aid, existing community social service programs, and programs that promote education and the arts.[90] [91]

This leads to a second important approach to strengthen community resilience in the face of long-term chronic abuse and systemic underinvestment. It is part of the history of many communities suffering from racial violence and inequality that efforts at building resilience are repeatedly undermined by insults such as redlining and communal displacement, increased incarceration and channeling residents in the criminal legal system, and failure to provide health, education, and housing services. One framework developed by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Culture of Health program envisions the strengthening of community capacity along three lines – promoting social cohesion, political or civic participation, and access to resources.[92] All three of these capacities may be harmed by systemic and police violence. To build social cohesion, it is important to understand how it has been hindered – communal fragmentation, polarization, and conflict are often the consequences of collective trauma. What strategies of organizing for social cohesion have been tried? What cultural mechanisms – like neighborhood festivals – have traditionally reinforced communal identity? What is the history of neighborhood organizations in promoting cooperation?

Political participation can be diminished by state repression. The recent demonstrations against violence and racial injustice that took place in Mott Haven may be seen by members of the community as a positive effort at political participation that was then crushed by police violence. Such efforts at participation need to be celebrated and reinforced along with other community actions that may have been strengthened as a consequence of protest.

A critically important component of helping strengthen community resilience is to foster a community building process to determine community priorities for reparations. As mentioned, it is important to memorialize the event of police violence in response to protest. Such events are important in the life of a community as examples of collective agency and civic participation, and as a powerful way of telling the community’s story of resistance. It is also important for the community to see that individual officers and NYPD leadership who are responsible for the police violence are held accountable and appropriately disciplined. The police violence that was perpetrated in Mott Haven and other communities in New York City must not be minimized – the types of injurious behaviors which were not prevented by police leadership is indicative of a particularly harsh and abusive approach to crowd control. Without severe reprimand and punishment, the police are condoning such behavior.

Material compensation for harms done and holding leaders and particularly violent police accountable for the police violence are important, but insufficient, as an effective remedy. Replacing just the leaders of a dysfunctional organization alone will not lead to effective reform. The community will still be living under ongoing threat and distress due to the underlying issues of racism and economic inequality that underlie both the dysfunctional police force and society in general. Police culture will not change from just outside pressure and accountability mechanisms, though these are necessary. The Department of Investigation report with recommendations for more effective oversight to prevent future police violence is insufficient to affect significant police organizational change and improve police/community relations. This is likely to be met with community skepticism and hopelessness in the absence of organizational change within the police department.

From a human rights perspective, there must be accountability and consequences for reckless, aggressive, and illegal behavior. There should be development of a broader collective narrative which places police violence in the context of societal racial injustice. This will first involve a process of truth telling, not just by victims, but also from bystanders, the general public, and the police themselves. Police violence is just the “sharp end” of a whole system of violence toward Black people, Brown people, and other oppressed communities in the United States. Structural change will not take place until what it means to be a person of color in U.S. society is raised and discussed honestly. People of color face an ongoing and daily threat from police, institutional and structural racism, and governments who continue to neglect these communities. This narrative needs a process of storytelling as well as symbolic acts of reparation – such as public memorials and other methods of remembering, naming streets, including education in schools, and teaching about the history of racial violence and its impact on society. Such symbolic reparation, however, must be accompanied by accountability and systemic changes. Changing the narrative must also include confronting the destructive permissiveness for violence against marginalized communities experienced under multiple presidential administrations, which has exacerbated anti-protest sentiment and the harsh approach to protestors by police forces.

The reparative process must also find a way to break the cycle of police violence, including the way that the United States polices. Participating in violence may itself lead to a range of mental health difficulties, from PTSD to substance abuse, domestic violence, moral injury, and suicide. Law enforcement may face retaliation for bringing attention to morally bankrupt behavior in their organization.[93],[94] Efforts should be made to support and protect whistleblowers who come forward to tell the stories of how police violence destroys communities.

To respond to the individual and collective harms stemming from the June 4 police violence in Mott Haven, we recommend guiding principles and call upon the Mott Haven community, activists, abolitionists, experts in police reform, and others to expand and develop these principles into meaningful actions. Recourse cannot be performative; there must be action that results in meaningful, measurable, and inclusive change.

Guiding Principles

1. The Mott Haven community must be involved in all decisions and plans.In order to promote community recovery, it is essential that community stakeholders be actively involved and represented in all decisions about appropriate compensation and redress. Such efforts should additionally include symbolic representations acknowledging collective harms from police violence in the community, such as the reparations ordinance and public memorial created in the south side of Chicago.[95],[96]

2. Increase funding for services that help meet social determinants of health. Health care services alone are insufficient for community and individual healing. Resources must also strengthen local capacity to provide needed social services, housing, employment, education, healthy food, green space, and other community services.

3. Inclusive, evidence-based, and person-centered mental health resources must be provided. There must be provision of funds for mental health support and treatment for individual protestors and community members. Resources need to be provided to enable those affected to receive evidence-based treatments for mental health sequelae from exposure to traumatic events. These include cognitive-behavioral therapy, exposure-based therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy to address social disruptions that may have occurred, as well as psychosocial, peer-based and other community-based approaches that have been found to be effective with marginalized communities.[i] There may be a need for both short- and medium-term behavioral health services. These services must be accessible, affordable, contextually sensitive, culturally and structurally informed, and appropriate to meet community needs.

4. Create a health care force that understands trauma. Support is needed for training and other measures to ensure that health care services for the community of Mott Haven meet the highest standards of “trauma-informed health care,” defined as health services “based on the knowledge and understanding of trauma and its far-reaching implications.”[i]

5. Law enforcement and governing must be aligned with anti-racist actions and policies. Measures must be taken to ensure trauma-informed governing, and that any required law enforcement interactions with residents are consistent with the trauma recovery process and reduce the risk of re-traumatization during encounters. If data on racial inequities is not already routinely gathered, analyzed, and made transparent, it is essential to begin immediately to monitor and document such inequities in order to identify racist practices and policies in law enforcement and governing. Systematic data collection is a necessary foundation to evaluate practices and policies.

6. There must be accountability for police officers who used excessive force. This is an important component of individual and community healing in the light of the psychological harms associated with impunity. There must be the guarantee that perpetrators of police violence will be disciplined and held to account by their departments.

7. Empower health care workers. Health care and public health workers are important allies to social and human rights movements and should be encouraged, supported, and funded to help make underserved communities like Mott Haven safer and healthier. In addition, emergency medical practices must be reviewed and reformed to enable the immediate provision of emergency medical care in protest and other situations in which police are involved.

8. Reforms must go beyond Mott Haven for equitable and meaningful change. It is essential to place the events of June 4 and the Mott Haven community within the larger picture. Governing bodies across the United States must rigorously examine police-community relations and the structures and systems that have allowed policing to be violent and trauma inducing.

Section Six: Summary and Conclusion