Executive Summary

Destruction of the health sector is a signature of the conflict which continues to unfold in Syria. It has occurred in the context of one of the most severe humanitarian crises in the world. Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and others have documented deliberate attacks on health care facilities and personnel during the past 10 years of this crisis, but less attention has been paid to the impact of these long years of conflict, human rights violations, and collapse of health systems on health and health care delivery.

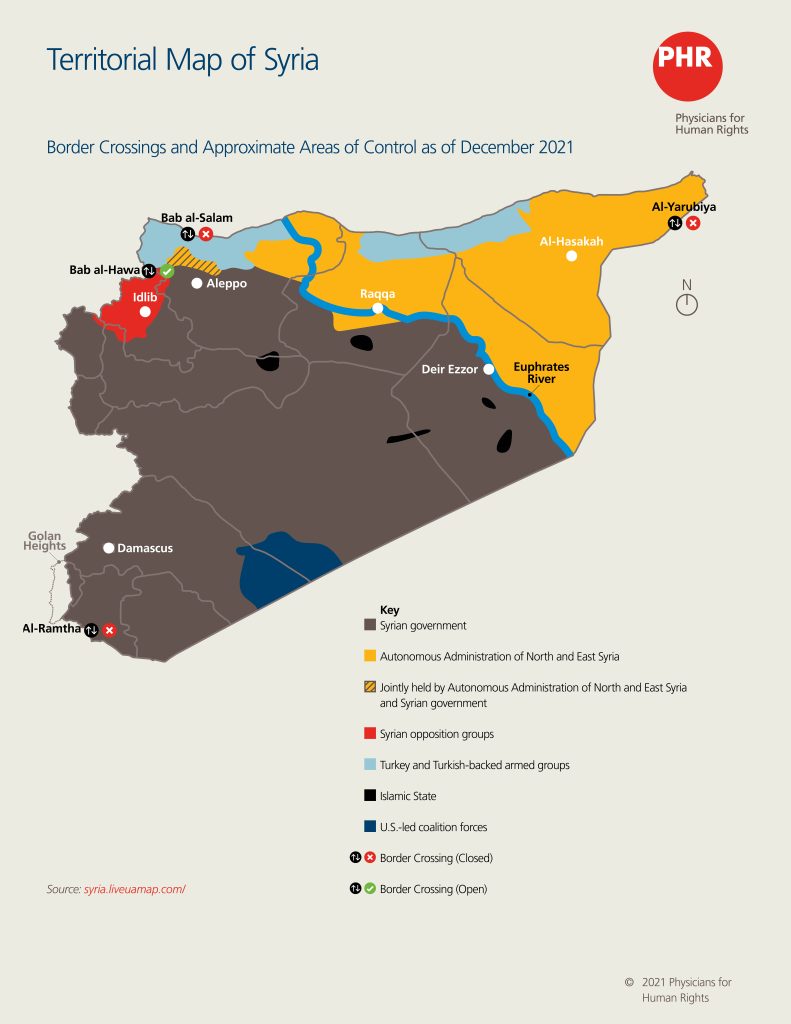

As of November 2021, northern Syria has been divided into three main areas: one controlled by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria in northeast Syria, another controlled by opposition groups in northwest Syria, and the third, the Turkish-controlled areas.[1] For this report, PHR conducted and analyzed 20 interviews with health care workers and experts knowledgeable about the health sectors working in these three areas. The PHR research team coded and systematically reviewed transcripts of the interviews to identify critical themes impacting the provision of health care in each area.

In this report, PHR describes how the Syrian government’s attacks on health infrastructure in northern Syria and its attempts to impede the delivery of humanitarian aid have driven the creation of a patchwork of health systems that has produced deep disparities in access to care, effectively denying people’s right to health. Understanding this complex issue is vital ahead of the United Nations Security Council’s upcoming meeting in January 2022 to consider whether to reauthorize the last remaining border crossing in northern Syria for UN humanitarian aid, Bab al-Hawa, which provides aid to 3.4 million people alone in northwest Syria, three million of whom are considered in acute need of lifesaving assistance.[2]

The Syrian government’s failure to deliver cross-line aid to needy areas from within the country spurred the Security Council’s 2014 resolution authorizing cross-border aid from other countries through four points in the north and south. Currently, the Bab al-Hawa border crossing in northwest Syria is the only entry point open to serve the humanitarian needs of people across northern Syria. In northeast Syria, the al-Yarubiya crossing was closed in January 2020 after Syria’s longtime ally, Russia, and China vetoed renewal of cross-border operations. This has caused the near collapse of the public health care system.[3] If the Security Council fails to reauthorize the Bab al-Hawa crossing, the Syrian government would gain full control over most humanitarian aid going to the north, a potentially disastrous outcome for the 6.4 million people living in areas outside the control of the Syrian government in northern Syria.

The Syrian government’s attacks on health infrastructure in northern Syria and its attempts to impede the delivery of humanitarian aid have driven the creation of a patchwork of health systems that has produced deep disparities in access to care, effectively denying people’s right to health.

Syria’s population arguably needs a functioning health care system more than ever before. Instead, the health system is straining from a decade of deterioration. Disparities that existed between government- and non-government-held areas prior to the conflict have become entrenched. Nine in 10 Syrians live below the poverty line.[4] Areas outside of government control, which host many internally displaced Syrians, have fewer resources but significant public health problems. For example, in northeast Syria, where health resources are reportedly most scarce, 55 percent of households are reported to have at least one disabled member.[5] Health choices are increasingly driven by scarcity and conflict, with women reportedly choosing cesarean sections to minimize time spent in the hospitals, which are known to be targets of attacks. By one estimate, the percentage of cesarean sections has more than doubled since the start of the conflict in 2011.[6]

This report provides a snapshot of the state of the health care systems delivery in northern Syria from August to October 2021, the period in which PHR conducted interviews. It demonstrates that the right to health of millions of Syrians is being violated by a lack of availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality of health care – all of which are mandated by international instruments to which Syria is a party. Furthermore, the lack of coordination among the international aid community, non-governmental organizations, and local actors overseeing health systems has greatly impacted population health, as has structural discrimination. Specifically, women and girls face a lack of gynecological and reproductive medical care because health care administrators do not prioritize these services, and people with physical disabilities face difficulty accessing repurposed buildings, let alone specialized care.

The lack of coordination among the international aid community, non-governmental organizations, and local actors overseeing health systems has greatly impacted population health, as has structural discrimination.

This report also details the challenges northern Syrian health systems face in their response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Northern Syria is now experiencing another major wave of the disease.[7] In September 2021, the number of coronavirus cases in the northwest increased 170 percent, intensive care units were filled, and designated COVID-19 health facilities reached 100 percent capacity.[8] Major issues include the diversion of resources away from non-COVID-19 health services, limited prevention and treatment supplies, and unstable funding for longitudinal pandemic management. Additional behavioral factors include lack of public adherence to health guidelines due to misinformation, financial barriers, and apathy towards the threat of COVID-19 among Syrian civilians. Women and girls in particular face barriers to accessing COVID-19 care that effectively deprive them of care.

PHR calls on donors, humanitarian actors, and all parties to the conflict involved in providing humanitarian aid to northern Syria to uphold the right to health as provided for in the Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, as well as the right to humanitarian assistance provided in the Geneva Conventions. PHR also recommends increased collaboration between donors and the humanitarian agencies they fund with local health ministries, health directorates, and health commissions across northern Syria to increase accountability for aid distribution and emphasize the importance of providing aid that is acceptable to and considers the needs of local communities. Donors and local actors alike must address structural discrimination against vulnerable populations.

PHR calls on donors, humanitarian actors, and all parties to the conflict involved in providing humanitarian aid to northern Syria to uphold the right to health.

Key Recommendations:

To the Syrian Government and Affiliated Forces, and All Parties to the Conflict:

- Fulfil the right to humanitarian assistance as provided for in international humanitarian law; and

- Promote the right to health in areas under their control, including non-discrimination with regards to distribution and accessibility.

To UN Security Council Member States and the International Community:

- Ensure the provision of humanitarian aid through cross-border supply, the most efficient way possible to deliver assistance to millions of people in need in northern Syria; and

- Reopen the Bab al-Salam and al-Yarubiya border crossings in northern and northeast Syria, respectively.

To International Donors and their Implementing Partners:

- Commit to funding health care in northern Syria, including direct funding support to local actors in providing health care, and to government-held areas where aid is not being adequately distributed;

- Apply the right to the health standards when delivering aid to ensure it is available, accessible, acceptable, and of requisite quality;

- Monitor aid delivery to prevent inequitable and discriminatory distribution of health services; and

- Condition international aid on the Syrian government’s demonstrated ability to provide assistance to areas that it currently controls.

Introduction

The violence in Syria is not over. In the decade since it began, it has engendered an extensive humanitarian crisis. Syria is the location of a protracted, low-intensity conflict that continues in areas outside of government control, punctuated by periodic airstrikes by the Syrian government and its ally Russia. Nearly half of Syria’s population remains displaced – including 6.7 million people internally displaced throughout the country and more than 6.6 million refugees and asylum seekers who have fled Syria.[9]

An estimated 13.4 million people across Syria need humanitarian assistance – needs which increased more than 20 percent in 2020 due to the combined impacts of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and severe economic decline across Syria.[10] As Syria has struggled to address the catastrophic spread of COVID-19 throughout the country, populations in the opposition-held territories in the northwest, the Turkish-controlled areas in the north, and the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria in the northeast have experienced the lack of a unified health sector, attacks against health facilities,[11] and barriers to accessing humanitarian assistance.

Population health needs far exceed the available facilities and personnel in northern Syria. The WHO recommends one hospital per 250,000 people;[12] however, the most recent Health Resources and Services Availability Monitoring System (HeRAMS) report from the Turkish Health Cluster covering April to June 2021 indicates that in northeast Syria, there were no functioning hospitals in two areas: Raqqa, which has an estimated population of 707,496, and Deir Ezzor, which has a population of 765,352.[13] Health care is instead provided at primary health centers and mobile clinics.[14] In al-Hasakah, there is one functioning hospital for a population of 1,127,309, roughly 20 percent of the WHO recommendation.[15] In northwest Syria and the Turkish-controlled areas, the number of health care workers – including doctors, nurses, and midwives – per 10,000 people falls far below the WHO recommended number of 22, with an average of nine health care workers across both areas.[16]

The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the depth of the disparities in Syrian health care. As of March 2021, the Syrian Ministry of Health reported having 6,326 beds to treat COVID-19 cases in isolation and quarantine centers in government-controlled areas.[17] In comparison, there were only 1,160 hospital beds and 1,088 beds in community-based treatment centers for handling COVID-19 cases in northwest Syria and Turkish-controlled northern Aleppo, respectively. In northeast Syria, as of February 2021, there were only 718 operational beds in COVID-19 facilities.[18]

Northern health care systems depend on a large and continuous flow of humanitarian aid to maintain services, including medications, supplies, human resources, and vaccines. Closing off this supply would debilitate these facilities and the organizations that support them. The Syrian government, in an apparent effort to control access to health care, has repeatedly attempted to impede the delivery of humanitarian aid to opposition-held areas.[19] In 2014, this led to the UN Security Council authorizing the use of cross-border aid delivery from Iraq, Jordan, and Türkiye through four international border crossings to supply opposition-held areas, including northern Syria. Currently, only the northeast border crossing of Bab al-Hawa remains open; the failure of the Security Council to keep it open would debilitate the northern health care systems’ facilities and the organizations that support them.

Political Actors and Territorial Control

The following table provides a general overview of factors influencing the health system in each of the three regions of northern Syria outside the control of the Syrian government.

Table 1: General Overview of Factors Influencing Northern Syrian Health Systems

| NORTHWEST SYRIA | TURKISH-CONTROLLED AREAS | NORTHEAST SYRIA | |

| Geography [20] | Comprises the northern half of Idlib governorate, parts of western Aleppo governorate, and sections of northern Latakia and Hama governorates. | Two noncontiguous areas along Syria’s border with Türkiye that include most of northern Aleppo and parts of northern Raqqa and al-Hasakah governorates. | Comprises most of Raqqa and al-Hasakah governorates and the territory of Deir Ezzor governorate east of the Euphrates River. |

| Major cities | Idlib, Jisr al-Shughur, al-Atareb, and Harim | Afrin, A’zaz, Ras al-Ayn, Tal Abyad, Jarablus, Mare’, and al-Rai | Raqqa, al-Hasakah, al-Tabqah, and Manbij |

| Population | 2.6 million[21] | 1.4 million[22] | 2.4 million[23] |

| Political entities with territorial control[24] | The Salvation Government (SG) and local councils | The Turkish government and the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) | The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) |

| Armed actors | Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (affiliated with the SG), Turkish-backed opposition groups, and several smaller jihadist groups. | Turkish military and the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (often referred to as the Free Syrian Army), which is affiliated with the SIG. | Syrian Democratic Forces, which is affiliated with the AANES, and the Syrian military |

| Control of the health system | The SG Ministry of Health controls Idlib Medical School and health facilities within Idlib city and other areas under its control. The Idlib Health Directorate operates independently of any government and oversees hospitals across opposition-controlled Idlib. | The Turkish government directly oversees health care in towns and cities through health directorates, with support from the SIG Ministry of Health in rural areas. | The AANES Ministry of Health oversees the health sector in northeast Syria through the use of health committees in each region. |

| Access to humanitarian aid | Northwest Syria receives nearly all its humanitarian aid through the UN-authorized Bab al-Hawa border crossing with Türkiye. The authorization will be reviewed by the UN Security Council (UNSC) for extension on January 10, 2022.[25] | The Turkish-controlled areas lost direct access to UN humanitarian aid after the Bab al-Salam border crossing with Türkiye was not reauthorized by UNSC Resolution 2553 in July 2020.[26] They receive some humanitarian aid from Türkiye and northwest Syria. | Northeast Syria lost direct access to UN humanitarian aid after the al-Yarubiya border crossing with Iraq was not reauthorized by UNSC Resolution 2504 in January 2020.[27] It is now dependent on the Syrian government for access to UN aid. |

Prior to the conflict, northwest and northeast Syria were among the least well-resourced areas in the country in terms of health care facilities. Over the last decade, the Syrian government’s control over the north has periodically shifted, leading to an eventual withdrawal of the Syrian Ministry of Health from non-government-controlled areas.[28] What follows is a description of the local health authorities in each area which have worked with local community councils, as well as donors and the NGOs they fund, to provide health services.

Northeast Syria

In northeast Syria, the Autonomous Administration Health Commission oversees the health system through “health committees” that operate across the region. In Deir Ezzor governorate, however, the Autonomous Administration exerts minimal influence on the health system, which is mostly overseen by a coalition of NGO workers and UN representatives known as the Health Working Group, overseen by the International Relief-led Northeast Syria Forum.

Since July 2020, only one border crossing between Türkiye and Idlib, Bab al-Hawa in northwest Syria, remains open, leaving the northeast without direct access to United Nations coordinated aid.[29] This has led to further disparities in humanitarian aid distribution throughout areas in northeast Syria outside of Syrian government control and has led to shortfalls in fulfilling the key determinants of health, let alone medical care that fulfils the right to health framework.[30]

Northwest Syria

In Idlib governorate in northwest Syria, the Idlib Health Directorate (IHD) has provided oversight of the health sector. Originally an independent network of health workers, the IHD developed into a de facto health ministry with links to the Syrian Interim Government and local health councils across Idlib.[31] A group of NGOs operating in northwest Syria committed to working within this local governance framework in September 2015 to promote donor collaboration and facilitate coordination of health policy;[32] many still operate in the region. The Hayat Tahrir al-Sham-backed Salvation Government became the dominant governing body of opposition-held northwest Syria in January 2019 (see Annex 1). The Salvation Government Ministry of Health overlaps territorially with the IHD but reportedly has little capacity or experience in managing a health system. This lack of capacity and experience, along with the lack of coordination with the IHD, has reportedly disrupted the health sector in this area.[33]

Turkish-Controlled Areas

In Turkish-controlled areas, Türkiye’s Ministry of Health supports major hospitals in cities such as Afrin, A’zaz, and Jarablus, while the Syrian Interim Government Ministry of Health supports health care in rural areas.[34] Türkiye has made significant investments in the health care system in the areas it controls. It has also imposed a piecemeal system of regulations that have hindered relief efforts, including by preventing Syrian and international humanitarian organizations from operating in Turkish-controlled areas without working through Turkish-approved organizations.[35] While regulation of the health sector is important for ensuring quality, Türkiye has used it to crack down on humanitarian organizations operating in northeast Syria in an apparent effort to limit the amount of aid reaching areas controlled by its perceived opponents, the Syrian Democratic Forces.[36]

Methodology

The findings in this report are based on 20 semi-structured interviews conducted by Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) researchers between August and October 2021 with stakeholders who have experience working in health systems in northwest and northeast Syria, including Turkish-controlled areas. In northwest Syria, respondents included health workers and health facility or hospital administrators, health system researchers, NGO staff, and donors. In northeast Syria, respondents included researchers, a health care provider, NGO staff, and UN representatives. In Turkish-controlled areas, respondents included health care administrators and a doctor. All respondents were selected for their knowledge of the current health care situation in each geographical area and for their firsthand experience responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in Syria.

Interviews were carried out using a semi-structured interview guide, which was developed in English and translated into Arabic by a native Arabic speaker and PHR staff member. Researchers with native Arabic and English skills conducted interviews remotely via Zoom. Most interviews were conducted in Arabic, with a small number conducted in English with international respondents. Following each interview, the interviewers conducted a debriefing to develop a codebook. The codebook reflected themes related to the health system, the right to health, humanitarian access, vulnerable populations, armed groups, relevant actors, COVID-19, non-medical challenges, recommendations made by respondents, and dynamics between actors. Primary data was then transcribed into Arabic and analyzed by Arabic-speaking members of the PHR team using qualitative coding software.[37] Findings were organized by key themes, which were assessed and formulated into legal and policy recommendations at the end of the report.

Researchers also conducted a desk review of academic and gray literature, using search engines including Google Scholar, WorldCat, and PubMed, with key words in English in combination with relevant geographic terms, including: human resources, health system governance, health information systems, medical supplies, technology, finance, governance, health infrastructure, and various types of health conditions (non-communicable diseases, mental health, nutrition, reproductive health, infectious disease outbreaks). The literature reviewed included open-source articles, UN agency reports, NGO reports, think tank white papers, and reports by media outlets on the health systems in northern Syria.

This report has several key limitations. It includes few perspectives from women in the health sector (n=2). Female staff inside Syria were hesitant to speak to the PHR research team for security and personal reasons. Other limitations include reliance on primarily English language resources for the desk review, as documents written in other languages, such as Arabic, Russian, and Turkish, were not included; the lack of recently published data about Syria’s population, public health issues, or health systems operating within Syria; and the challenge of documenting the needs of medical facilities in areas outside of Syrian government control due to ongoing fears of personnel working in these facilities facing retaliation from local actors for discussing mismanagement of resources, corruption, and other sensitive topics.

“The first challenge is the continuous bombing and targeting of health facilities by the Syrian and Russian regime. This constant fear and terror, we do not know at what moment the facility, including its employees and equipment, can disappear.” [38]

Female administrator, Gaziantep

Findings

Ongoing Physical Insecurity: Attacks on Health Care Facilities and Workers

As has been well-documented, violence against health care workers by the Syrian government, its allies, and other armed actors has impaired the health sector’s ability to function. A doctor from northeast Syria reported that in the first half of the conflict, health care workers in Syria established temporary field hospitals in businesses and private homes to avoid repeated aerial attacks on formal health facilities.[39] Attacks continue to preoccupy health care workers and take a psychological toll. A general surgeon from Deir Ezzor expressed concern that any large, well-staffed hospital with supplies and equipment can expect “to be targeted at any moment” and attacked.[40]

The current health crisis in Idlib’s Jabal al-Zawiya region demonstrates the effects of the periodic attacks. Türkiye and Russia negotiated a 2018 ceasefire that allowed northwest Syria a period of relative stability, and the health system in most of Idlib improved. However, in Jabal al-Zawiya, health care services rapidly deteriorated because opposition forces there continued to operate.[41] Before the ceasefire, there were several hospitals in Jabal al-Zawiya district. Due to security concerns, many health workers fled to safer regions, and NGOs stopped supporting health facilities in the area.[42] By 2019, only one medical point remained, the Mara’ayan Medical Center.[43] On September 8, 2021, this last facility was destroyed by an unknown actor operating from an area jointly controlled by the Syrian government and the Syrian Democratic Forces,[44] leaving Jabal al-Zawiya district without a health facility.[45] An administrator of a hospital in a nearby town cited the uptick of patients to his facility after this attack: “Two weeks ago, there was an attack on Jabal al-Zawiya right next to the hospital [effectively destroying it]. In the southwest part of Idlib, there are not many hospitals. If an attack happens far away, patients come here.”[46]

“With regard to cross-border aid, it is the window through which we breathe, and it must not be closed…. The health sector is walking on a crutch, and [if] this crutch is broken, it will bring down the sector.”[47]

NGO administrator, Idlib

Cross-Line vs. Cross-Border Aid

Humanitarian access is essential to meet the most basic needs of the health systems serving the more than 6.8 million people in need of humanitarian assistance in all areas of northern Syria, including areas held by the Syrian government.[48] The dynamic security situation and fluctuating donor priorities threaten humanitarian actors’ ability to provide lifesaving care and sustainable support. Some respondents indicated that the situation was not much better in government-controlled areas.[49]

International humanitarian law guarantees civilians the right to lifesaving assistance in areas affected by conflict.[50] The two main ways of delivering humanitarian aid to affected populations in Syria are through “cross-line” and “cross border” operations. “Cross-line” delivery occurs within Syria, from government-held to non-government-held areas. It usually involves overland convoys, although in a few cases shipments have been made by air.[51] “Cross-border” aid is delivered by convoys from other countries directly into non-government-held areas. Cross-border aid into Syria now comes exclusively from Türkiye, although in the past it also came from Iraq and Jordan.

On July 14, 2014, United Nations (UN) Security Council Resolution 2165 authorized UN humanitarian agencies and their partners to provide humanitarian assistance to Syria through four international border crossings, “to ensure that humanitarian assistance, including medical and surgical supplies, reaches people in need throughout Syria through the most direct routes” (emphasis added). [52] Resolution 2165 established two such border crossings at Bab al-Salam and Bab al-Hawa along the Syrian-Turkish border, a third at al-Yarubiya on the Syrian-Iraqi border, and a fourth, al-Ramtha, on the Syrian-Jordanian border.[53]

Aid organizations channeled significant humanitarian aid to millions of people using these four border crossings. In recent years, Russia – an ally of the Syrian government – and China have used their veto or threats of vetoes in the Security Council to trigger the incremental closure of the border crossings. The lifeline for humanitarian assistance in Syria has therefore been reduced to one border crossing, which the UN Security Council has repeatedly reauthorized for six months at a time.[54] This has placed significant pressure as well as instability for planning on the Bab al-Hawa border crossing, which supplies aid to the entire northern Syria region, including northeast Syria, where humanitarian needs continue to increase. While non-government-controlled areas can, in theory, receive humanitarian aid coordinated through Damascus, PHR’s 2020 report about the obstruction and denial of humanitarian access in opposition-held areas retaken by the Syrian government in the south demonstrated the failings of that system.[55]

A doctor in northeast Syria estimated that doctors working in a public hospital see “40-50 patients in two hours” and that “usually 150-200 patients are waiting.”

A Snapshot of Northern Syria Health Care Systems

Although each region discussed in this report is different, they share common problems related to availability of and access to health care facilities. PHR’s interviews with administrators, health care workers, and researchers describe health systems crises in northern Syria, in which health care availability and access differed significantly. Across all areas, respondents indicated that, overall, the number of health facilities and staffing was insufficient for the population.[56] Even in Idlib, which was relatively well-served, only 600 doctors served a population of approximately four million in 2019, 15 percent of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommendation for physician staffing.[57] High patient loads have created significant stress for health care workers and have further pushed health care workers to leave Syria. A doctor in northeast Syria estimated that doctors working in a public hospital see “40-50 patients in two hours” and that “usually 150-200 patients are waiting.”[58]

Funding, Location, and Transportation

Each region’s health ministry oversees its own system; respondents indicated that the majority of funding and supplies comes from international aid. Public, private, and NGO-run health facilities exist in a loose framework without strong coordination mechanisms. Individual hospitals and clinics have been forced to compete for funding and supplies in the absence of these mechanisms. Health administrators, health care providers, and researchers all reported significant differences in the amount and level of health care available among the regions, as well as within a given region and in particular communities. For example, northeastern communities in Deir Ezzor and Raqqa governorates have less access to health care services than those in al-Hasakah. Donors are hesitant to invest in these areas, given access constraints due to ongoing security dynamics.

Health facilities in all three areas are concentrated in urban areas, leaving rural and other populations with little to no access to health care. Respondents reported that, as a result of security factors and donor prerogatives across all three territories, health facilities were created in geographical “clusters,” resulting in a relative abundance of health care in some areas and none in others. Additionally, vulnerable populations, including women and physically disabled people, were among those most severely impacted, as discussed further below.

Travel is expensive and dangerous across northern Syria. Patients in underserved areas are forced to travel long distances, ranging from six to more than 370 miles, depending on the type of care required.[59] Transportation costs are a serious barrier to most families, especially if multiple trips are required.[60] In al-Atareb, in northern Aleppo, the estimated cost in June 2021 for a one-way trip to the nearest surgical hospital was $25, an amount 17 times the average daily income.[61] Patients face additional security risks when traveling through checkpoints manned by armed groups between areas for medical care.[62]

“Most hospitals do not have ambulances. Most health centers do not have doctors.”[63]

Administrator in a health facility in Deir Ezzor

Northeast Syria

Since 2019, the Syrian Democratic Forces, the military that supports the government of northeast Syria, has worked with the Syrian military to repel the Turkish military’s incursion into northern Syria. In Deir Ezzor governorate, the Syrian government controls the area to the west of the Euphrates, and the Syrian Ministry of Health provides some funding and aid for that part of northeast Syria’s health system, although it reportedly does not meet local needs.[64] In the northeast, the Autonomous Administration Health Commission oversees the health system through “health committees” that operate across the region. The health system in Raqqa depends heavily on international humanitarian aid, which is administered through local NGOs that rely on funding from the United States to provide services. This funding was halted in March 2018, and although it has since resumed under the Biden administration, U.S. officials project that the effects of the funding freeze will continue through 2022.[65] To the east of the Euphrates in Deir Ezzor, the Autonomous Administration exerts minimal influence on the health system. The Health Working Group, which oversees the health system to the east of the Euphrates, is modeled on the WHO-led Health Cluster operation based in Gaziantep, but respondents indicated that it lacks the resources to serve as a coordination mechanism.[66] In addition, the political struggles between the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria and the Syrian government have created a difficult environment for humanitarian organizations.[67]

The UN estimates there are 1.9 million people in need of humanitarian aid in northeastern Syria alone.[68] The closure of the al-Yarubiya border crossing in January 2020 forced its population to rely on cross-line aid from adjacent regions within Syria, specifically Turkish-controlled areas and areas under Syrian government control. This reportedly resulted in severe shortages of medical supplies, including “medications to treat diabetes, cardiovascular and bacterial infections, as well as post-rape treatment and reproductive health kits.”[69] The problems that resulted from suspending cross-border aid to northeast Syria exemplify the impact on the right to health and humanitarian assistance if humanitarian supplies are not delivered efficiently. For example, soon after the al-Yarubiya border closure in January 2020, there was reportedly a significant coordination problem with delivery of assistance from inside Syria, including the routing of 85 metric tons of medical supplies to Damascus and a nine-month delay before they were sent to northeast Syria, by which time many of the medications had expired.[70] Land-based cross-line operations are fraught with danger, even when the government has granted permission for them to take place.[71] This allowed the Syrian government to ship aid by air to Qamishli, where the Autonomous Administration is based; reportedly, this aid reached only the health facilities in government-controlled areas within northeast Syria.[72] In 2020, only 31 percent of medical facilities in northeast Syria benefited from cross-line humanitarian assistance from Damascus.[73]

Northeast Syria has therefore become almost completely dependent on aid that is transported by land from the Bab al-Hawa crossing in the northwest through Idlib and the Turkish-controlled areas, a journey of at least 275 miles. A hospital administrator in Deir Ezzor reported that small quantities of medications are delivered every three to four months and are often limited to painkillers and antibiotics.[74] Health facilities must factor in the cost of transportation and the payment of bribes to different actors, which can easily triple the price of medications.[75]

Although overall northeast Syria is the least resourced of the three areas, there are multiple health facilities in the governorates of Raqqa and al-Hasakah in the northern part of the region. In 2020, there were reportedly three partially functioning public hospitals in Deir Ezzor governorate on the western bank of the Euphrates River, in territory controlled by the Syrian government. In contrast, the area of Deir Ezzor governorate to the east of the Euphrates River, controlled by the Autonomous Administration – which had an estimated population of 300,000 in 2018 – has had only one large public hospital supported by an NGO, in the town of al-Shaheel.[76] These disparities can be traced back to former ISIS control of these areas,[77] when, according to a doctor practicing in Deir Ezzor,[78] “most doctors in Raqqa and Deir Ezzor fled to Türkiye and [Syrian government-controlled] areas.”[79] He said that many health workers have not returned.

Some health care workers attribute the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration’s perceived lack of engagement with the health system in Deir Ezzor to discrimination against the Arab population living there. The doctor practicing in Deir Ezzor noted that the lack of NGO activity could be due to the dominance of tribal factions[80] and an absence of stability or civilian institutions in the greater Deir Ezzor area:

“Al-Hasakah and al-Qamishli have security, safety and electricity, and courts. In our areas, there are no courts, no police…. Organizations like to go to a secure area in which there is a judiciary, police, and courts. Our areas are governed by tribalism.”[81]

Most training opportunities for health care workers are concentrated in the areas where the Autonomous Administration has direct oversight and where NGOs can operate in more secure conditions, including al-Hasakah and al-Qamishli. This poses challenges for Arab health care workers from under-resourced areas, such as Deir Ezzor and Raqqa, who want to access these trainings. At the same time, ethnically Arab health care providers expressed hesitancy about working in Autonomous Administration-managed facilities. One doctor explained,

“If things changed on the ground, and we ended up needing to go to Free [Syrian] Army[82]-controlled areas or to Türkiye, we might be arrested for having worked with the Syrian Democratic Forces (the military arm of the Autonomous Administration).”[83]

Remote areas along northeast Syria’s border with Iraq are especially underserved, as there are few doctors and the nearest health facilities are hours away along unpaved roads through rugged terrain.[84] For some patients, a trip to a health facility can be a multi-day journey with no guarantee that the treatment they need will be available when they arrive.[85]

Northwest Syria

Two competing opposition entities in Idlib claim control over overlapping areas in which health care is provided (see Table 1). A cardiologist in Idlib described how the competition between the Idlib Health Directorate and the Salvation Government Ministry of Health has resulted in a vacuum of health policy. Subsequently, the funding choices made by donors and international organizations play a significant role in determining local health priorities.[86] A health care professional in A’zaz, in the Turkish-controlled areas, noted that donors prefer to invest in projects in Idlib because it has “a larger population [than northeast Syria or the Turkish-controlled areas], which means that more projects are implemented there, and because organizations have greater presence and weight there.”[87]

The UN estimates that 3.4 million people require humanitarian aid in northwest Syria; as of June 2021, UN aid through the Bab al-Hawa crossing reaches 2.4 million Syrians each month, leaving one million without adequate assistance.[88] In August 2021, a single cross-line shipment of aid was delivered to northwest Syria.[89] Residents of northwest Syria and humanitarian actors protested, fearing it might be an attempt by the Syrian government to demonstrate that cross-line operations can replace the much larger cross-border mechanism.[90] The Idlib health care provider cautioned, “Stopping [aid through] the Bab al-Hawa crossing is a sentence for the region to fall.”[91] The UN Secretary-General noted that cross-line aid, “even if deployed regularly, could not replicate the size and scope of the cross-border operation.”[92] Health care workers in Idlib distrust and fear aid delivered through Damascus. A health care administrator in Idlib noted,

“There is complete lack of trust in the Syrian authorities working from Damascus to secure health care services in areas outside of its control. On the contrary, we think a regime that bombards hospitals cannot be trusted to send medications and treat people.”[93]

Even in comparatively well-resourced northwest Syria, many areas lack access to health care. A cardiologist in northwest Syria explained that most people in underserved areas who need medical care must borrow or rent a car, endeavors that have continuously increased in price due to rising costs of fuel and the impact of the conflict on the local economy.[94] Patients living near large hospitals might be able to request an ambulance or receive transportation assistance from organizations like the White Helmets, first responders who provide ambulance services,[95] but remote, mountainous areas like Jabal al-Zawiya, Jisr al-Shughur, Darkush, and Salqin are far from northwest Syria’s large hospitals,[96] which are located along the border with Türkiye, away from active areas of fighting.[97]As a result, patients in those areas are forced to travel at great costs through dangerous routes to access care.

Because humanitarian aid fails to meet population needs, some humanitarian aid flows into northern Syria by informal smuggling at crossings with Türkiye and Iraq. A health care provider explained that he and his friends resorted to smuggling surgical equipment across the border.[98] He also reported that bribes must be paid, adding to the cost of delivering supplies.

“Local councils manage themselves independently. Turkish hospitals manage themselves independently…. Today, there is not any real planning here or in northwestern Syria, in Idlib.”

Health care provider, A’zaz

Turkish-Controlled Areas

In Turkish-controlled areas, the health system is overseen by the Turkish Ministry of Health, with the Turkish-backed Syrian Interim Government addressing needs in rural areas.[99] Health care has gradually improved in some of the areas in which Türkiye took control through its military campaigns from 2016 to 2019; others, such as Ras al-Ayn and Tal Abyad, remain in great need. Some Syrian health workers have criticized Türkiye for tightly regulating the health sector without providing meaningful planning or coordination support.[100] A health care provider in A’zaz confirmed that the lack of coordination between Turkish health authorities, NGOs, and the private sector has led to an abundance of services in some places, while other areas remain unserved.[101] An administrator in a health facility in A’zaz described this phenomenon, noting, “A’zaz has two women’s hospitals, about 200 meters apart. In another area there are villages with no medical service.” He further explained the political reality behind this inequality:

“We have become mini states in the north. The statelet of A’zaz is not the statelet of Mare’, or the statelets of Jarablus and al-Bab. Each one is a little state acting on its own, with a local council acting on its own. Frankly, [Türkiye’s] policies have encouraged this division and support it.”[102]

In areas where services are available, they do not always reflect community needs. For example, the health care provider in A’zaz observed that the number of primary health care centers exceeds the current need, but the quality of health care they provide is very basic.[103] It has become practically impossible for patients with chronic illness or significant injuries to cross into Türkiye for secondary or tertiary care.[104]

Populations Most Adversely Affected by Health Disparities

While the entire population of northern Syria reportedly suffers from lack of availability and access to adequate health care, multiple respondents mentioned the disproportionate impact of poor health care governance on women and people with physical disabilities.

Health Care for Women and Girls

Northeast Syria

In the northeast, women’s health is limited mainly to routine reproductive health visits and family planning. Specialized medical services for women with ovarian cysts are not supported because organizations consider it a non-primary condition. Similarly, few health care workers in the region have the experience and equipment to diagnose and provide appropriate medical prevention and care for breast cancer. A midwife in Raqqa noted the rise in breast cancer rates and the attendant need for mammograms, stating, “Al-Tabqah, Raqqa, and Manbij do not have any [machines for performing] mammograms. We rarely find a specialist who has experience detecting it.”[105]

In addition to the lack of gender-specific health services, women and girls face formal and informal barriers to accessing health care, including access to female providers.[106] Female patients may prefer – or are culturally expected to be seen by – female providers, yet female providers are rare. Women across Syria are often accompanied for protection by their husbands or male relatives when they travel to access health services.[107] Even female health care workers may be stopped at checkpoints and prevented from reaching patients if they are not accompanied by a male family member.[108] Adult men may avoid crossing checkpoints to avoid detention, which would pose potential travel constraints for women and children seeking care across territorial lines. Women and girls displaced from urban to rural areas are particularly affected, since they are often in unfamiliar settings without the male family members needed to accompany them to access care.[109]

Northwest Syria

A sexual reproductive health technical advisor in Gaziantep who oversees health programming in northwest Syria explained that when health services began to shift to field hospitals in response to aerial assaults by the Syrian government, health facilities functionally stopped providing reproductive health care.[110] The gap widened as the destruction of health facilities and loss of health workers reduced and eliminated services. As health systems were slowly repaired in areas benefiting from ceasefire agreements, she noted that reproductive health care was not prioritized and lagged behind other services.[111] She explained that attempts by NGOs to finance and support health services for women, including reproductive health care, have been met with systemic obstacles. For example, when health care organizations have provided training on health services for women, health workers have shown little interest and lackluster engagement. The same technical advisor indicated that some Syrian health officials have dismissed women’s health care and protection issues as unimportant compared to conflict-related health care or drug addiction.[112]

The sexual reproductive health advisor also noted that implementation has sometimes suffered from the absence of female health experts in decision-making positions in organizations that had invested in providing women’s and reproductive health care.[113] She stated, “When I meet with organizations, [the staff] are all males. There is no female in an important position to talk about the reality of the women and girls to whom I provide humanitarian aid.” Even when providing essential feminine hygiene products, such as sanitary napkins, she reported that lack of knowledge led to issues with the quality of supplies.[114]

The absence of qualified medical personnel has shaped access to health care for women and girls. Without skilled obstetricians and midwives, the rate of natural births has dropped as pregnant women, seeking to control the time of delivery, have opted for cesarean sections. A female NGO administrator working on women’s health issues in northwest Syria estimated that 40 percent of births in Idlib are now cesarean sections, compared to only 19 percent across Syria in 2011.[115] A midwife working in Raqqa reported a similar phenomenon in northeastern Syria.[116]

57 percent of households in northwest Syria and 55 percent of households in northeast Syria have at least one person with a disability. As many as 30,000 new cases are added each month to the number of people with disabilities in Syria.

Access Issues for People with Physical Disabilities

The UN Humanitarian Needs Assessment Programme (HNAP), a joint UN assessment for determining population needs in Syria, estimated in 2020 that 13 percent of the entire Syrian population has a disability affecting mobility.[117] Significantly, HNAP estimates that 57 percent of households in northwest Syria have at least one person with a disability, and 55 percent of households in northeast Syria have at least one person with a disability.[118] Researchers estimate that as many as 30,000 new cases are added each month to the number of people with disabilities in Syria, caused by a combination of war injuries due to explosions and other violence, and disabilities caused by sequelae of untreated illness such as strokes and diabetes.[119]

The disabled population includes 14 percent of people in Idlib, 15 percent in al-Hasakah, 16 percent in Aleppo, 18 percent in Deir Ezzor, and 25 percent in Raqqa.[120] Respondents indicated that the use of repurposed buildings as primary-care health points has limited access to health care for people with physical disabilities. A surgeon working as a director for an organization based in Gaziantep, Türkiye covering northwest Syria explained that in facilities with multiple floors, the lack of elevators and other accessibility features creates additional hurdles for patients with physical disabilities.[121]

Specialized services for people with disabilities are reportedly rare. For example, the midwife in Raqqa explained that for the many people who have lost limbs due to mines and other conflict-related injuries, prosthetics are unavailable.[122] She reported that wheelchairs and crutches were in short supply, and cost poses a substantial barrier. She noted, “An electric wheelchair costs $5,000, a regular wheelchair is $150, and a crutch is $25. If the wheelchair breaks, it will not be replaced.”[123] Even the cheapest options are unaffordable to local populations struggling with poverty: the average laborer in northwest Syria made 69 cents a day in January 2020.[124] The same midwife expressed concern that conflict-related injuries, such as hearing loss due to explosions, have increased and that the limited treatment services available are prohibitively expensive.”[125]

Locally Led Approaches in the Coordination of Humanitarian Aid

Local NGOs have spearheaded the humanitarian health response in northern Syria, supported by international NGOs and their respective donors. The UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs indicates that 25 local health sector organizations operate in northwest Syria and 37 in northeast Syria.[126] The WHO-led Health Cluster coordinates the humanitarian health response in northwest Syria by meeting regularly with health organization representatives based in Gaziantep, across the border in Türkiye. In northeast Syria, the Northeast Syria Forum oversees all health sector responses.[127]However, in both areas, community-led approaches are lacking to identify critical health needs and provide insights on challenges and solutions for these communities.

A Syrian health researcher respondent highlighted the significance of ground-up approaches to humanitarian programming in northeast Syria:

“In northeast Syria, there should be more links between the different levels – the main level of the health department of the Autonomous Administration should have more links with other governorate levels as well as the sub-district level. More work should be done to decentralize health policies; for example, each governorate – Raqqa, al-Hasakah, and Deir Ezzor – should develop its own local health policies and the health department in the Autonomous Administration should coordinate to harmonize these approaches.” [128]

He also observed that models for coordination, like the Health Cluster cross-border operation led by WHO from Gaziantep, are effective but require support to be sustainable:

“In northwest Syria, there have been some innovative practices that need to be supported to ensure sustainability…. Projects that use this bottom-up approach increase the link between international and local actors. For example, they have clusters in Gaziantep that include local actors and encourage them to participate in decision-making. This needs to be maintained and supported.”[129]

Turkish authorities have permitted local NGOs in Turkish-controlled areas to establish primary health care centers. However, the researcher noted that “In northern Aleppo [administered by Türkiye], there should be some local Syrian lead. The Turkish Minister of Health should work with a local health authority – for example, the Aleppo Health Directorate or even the [Syrian] Interim [Government] Ministry of Health or any Syrian lead entity – to plan for the health system in this region.”[130]

COVID-19 Response in Northern Syria

In addition to the struggles with availability and access outlined above, the COVID-19 pandemic has put additional strain on the already weak health systems in northern Syria. The rollout of COVID-19 programming – including the creation of isolation and treatment facilities, new health guidelines, and vaccine campaigns – has been impeded by pre-existing disparities in health care capacity, limited patient access, and lack of trust in institutions. These problems are overlaid on the existing gaps in each system.

In 2020, global public health workers feared the COVID-19 pandemic could sweep through the dense and economically vulnerable populations in northern Syria. To prepare, there was a push by donors and NGOs in northern Syria to establish COVID-19 isolation centers and hospitals and to train health care workers. However, in each region, many Syrians chose to avoid seeking treatment for COVID-19 for a mix of economic and cultural reasons. International actors, including the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) initiative, have worked to ensure access to COVID-19 vaccines in northern Syria, largely through the Bab al-Hawa border crossing. However, the same issues with availability, access, and hesitancy apply. Vaccine hesitancy in the populations of northern Syria is reportedly widespread, often stemming from mistrust in institutions and the spread of rumors and misinformation regarding COVID-19 vaccines.[131]

The number of coronavirus cases in the northwest increased 170 percent in September 2021, filling the intensive care units as COVID-19-designated health facilities reached 100 percent capacity.

Funding: Shifting Priorities for Donors and Providers

Concern over the spread of COVID-19 in non-government-controlled areas led to donors restructuring their health programming priorities in northern Syria. Though this resulted in a surge in funding for COVID-19 prevention and management projects, the resource reallocation came at the expense of other health services. An administrator in Idlib described how the pandemic “forced some health centers to turn into COVID-19 centers, and people had more difficulty accessing health centers.”[132] He further explained that the pandemic greatly affected the decisions of the donor organizations “that carry the health sector” because much of their support was shifted towards establishing community isolation centers. [133] The distribution of these COVID-19 activities appears to have been uneven, however. Health care staff covering both northwest Syria and Turkish-controlled areas expressed concern about the availability of COVID-19 services.

International funding from donors for many COVID-19 projects is set to expire, despite the fact that Idlib is now experiencing its largest wave of COVID-19 cases yet.[134] The number of coronavirus cases in the northwest increased 170 percent in September 2021, filling the intensive care units as COVID-19-designated health facilities reached 100 percent capacity.[135] Health care workers in facilities in northwest Syria are increasingly forced to make difficult choices about who can get care.[136] A surgeon from Idlib reported that oxygen shortages in his hospital have forced them to stop all elective surgeries to conserve oxygen for emergency surgeries and the newborn intensive care unit.[137] A respondent from Idlib reported his belief that the priority should be “to finance COVID-19 hospitals, even if support for isolation centers stops. If you choose between the two, hospitals are more important. It is lack of funding that will determine the health sector’s ability to respond to the potential peak.”[138] Another respondent from Idlib stated, “If the disease spreads again, we do not have enough hospitals and sufficient centers. There are some community isolation centers and corona hospitals … but [the health system] certainly will not survive a pandemic.”[139] The surgeon from Idlib explained, “We have 10 rapid tests in our hospitals. That’s it. We sent the patients to the isolation center – which ran out of rapid tests,” adding that currently health care providers diagnose based only on symptoms.[140]

Widespread poverty has had an enormous impact on people’s ability to follow COVID-19 guidelines. Across the country, nine in 10 Syrians live below the poverty line. The majority of the population relies on humanitarian aid.

Poverty’s Role in Determining Adherence to COVID-19 Protocols

Widespread poverty has had an enormous impact on people’s ability to follow COVID-19 guidelines. Across the country, nine in 10 Syrians live below the poverty line.[141] The majority of the population relies on humanitarian aid. Although it is difficult to track current wages, in December 2020, northwest Syria reported the lowest wage rate in the country (SYP 3,325 or $1.32 a day), followed by northeast Syria (SYP 4,343 or $1.73 a day).[142] Socially distancing from work while symptomatic would be difficult for those who could not afford to lose even a day’s work. An administrator in a health facility in Idlib explained that resistance to prevention practices is based partly on poverty, noting, “If the day laborer works, he eats. If he does not work, neither he nor his family eats.”[143] An administrator in Idlib explained that some people who contract COVID-19 have concealed their condition to avoid social and financial repercussions.[144]

An orthopedic surgeon expanded on this issue, noting the prohibitive expense of personal protective equipment (PPE) could lead to a public health disaster in northern Syria:

“Masks, gloves, and sterilizers are available in general. People did not go out to buy them due to the economic situation…. In Türkiye, in the first wave, they distributed masks to people, who took them for free at the pharmacy. In Syria, there are no possibilities and no preparation, if a major pandemic begins, there is nothing to stop it.”[145]

COVID-19 has added a layer of challenge due to global competition for supplies, placing a more significant strain on humanitarian workers to secure medical supplies by any means possible. In March 2020, Türkiye prohibited the export without pre-approval of many kinds of medical equipment and supplies, including PPE, ventilators, oxygen concentrators, and intensive care monitors.[146] The Turkish export ban forced NGOs in northwest Syria to procure the necessary supplies on the black market from inside Syria with difficulty and at great cost.[147]

COVID-19 in Northeast Syria

Respondents indicated the COVID-19 response in northeast Syria has been weak and unsustainable. As discussed above, the northern areas, including al-Qamishli, benefit from many of the health resources, while Deir Ezzor has one functioning public hospital for the entire governorate, and few health facilities. An NGO mission director whose organization covers Raqqa and Deir Ezzor explained that humanitarian organizations have provided intermittent support to isolation and COVID-19 centers, but

“Once the [COVID] wave ends, so does the funding. In Deir Ezzor, at the start of the second wave, only one out of four COVID-19 and isolation centers was functioning. The other three had closed after their funding stream was suspended.”[148]

A general surgeon working in Deir Ezzor described how patients slept on their own bedding on the isolation center floor because there were more than three times as many critical patients as available beds:

“When COVID-19 hit, in Deir Ezzor, the COVID-19 center had 40 beds, but there were approximately 130 patients in critical need. People used to sleep on the floor. They would bring their mattress and cover from home. We are talking here about critical cases that require oxygen.”[149]

The lack of capacity reportedly impacted testing. An NGO program manager explained that, in the early phases of the pandemic, there were no COVID-19 labs in the northeast. Instead, health authorities would send PCR tests by air from al-Qamishli to Damascus.[150] Reportedly, there is now one laboratory in al-Qamishli and PCR tests are free, with the results provided in 48 hours. However, there are constant complaints about the lack of PCR kits. The same staff member reported that for three months the al-Qamishli lab had been “calling for more kits. This lab covers al-Qamishli, al-Hasakah, Raqqa, and Deir Ezzor. This lab’s response is very weak compared to the needs.”[151] As a result, the NGO mission director stated that “no one trusts the official reported cases of COVID because the lab itself does not have enough number of kits.”[152]

An NGO administrator explained that since Deir Ezzor is a very large governorate, his hospital had wanted to fund a project to establish its own PCR lab there. However, he noted that “the local authority refused and there was no room at all for discussion,” adding that “they considered it [a] political [matter].”[153]

The administrator noted that the lack of PCR tests and laboratories resulted in underreporting in regions without them, highlighting the disparities between areas in the northeast:

“The [reported] numbers are wrong. For example, last month in al-Hasakah, there were 1,500 positive cases compared to 63 in Deir Ezzor. This is mainly because in al-Hasakah, the distance between where the swab is taken and the lab takes only a few minutes, but swabs in Deir Ezzor can take four to five days to arrive [at the lab] in Qamishli. Most arrive damaged.”[154]

In Raqqa, an NGO staff member reported that vaccines are freely available at fixed vaccination points for anyone who wants one; however, there are high rates of vaccine hesitancy.[155] A surgeon in Deir Ezzor explained:

“People in the northeast do not trust the regime. Since the vaccines provided by the World Health Organization were delivered to the Syrian government and then transferred to areas held by the Autonomous Administration, people didn’t accept [the vaccines] because they thought they had been tampered with.” [156]

He added that doctors and health care workers were among the largest percentage of those vaccinated, “because it was explained to us that the vaccines were coming from the WHO and that the regime had not interfered in the process.”[157] As of November 4, the WHO reported that 42,077 people in northeast Syria had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, including 20,885 who had received a second dose.[158]

COVID-19 in Northwest Syria

In neighboring Idlib, ventilators have become more readily available than in other areas,[159] yet the need is greater than the supply. The surgeon in Idlib stated, “We see people die in front of our eyes for many reasons. Now, we see people dying from a lack of oxygen. Türkiye is next to us – why can’t we receive oxygen cylinders [from Türkiye]?”[160] According to the Syrian American Medical Society, the lack of oxygen stems from difficulties in the supply chain, including the logistical challenges of maintaining oxygen generators, procuring spare parts, and transporting oxygen cylinders over poorly maintained roads.[161]

The global impact of COVID-19 also resulted in some international donors withdrawing from their commitments as their economies were impacted and they began focusing on their own COVID-19 responses. An administrator from Idlib reported that his organization has struggled to deal with the loss of a major donor from East Asia when it fully cut funding in 2020.[162]

In Idlib, health care staff were reportedly trained on COVID-19 protocols. An NGO administrator in Idlib stated, “Almost all the health sector has been trained on coronavirus procedures. My organization worked on capacity building in this field and included almost all health personnel. People are ready to deal with disease.”[163] Another respondent, a cardiologist, added that, at first, an orthopedist ran the COVID-19 program but that eventually internists were recruited.[164]

An administrator in Idlib noted that cultural issues may prevent effective management of the virus:

“The biggest problem is what happens after entry into the community COVID-19 center. The measures were not encouraging for people. For example, when a patient enters the isolation center, he was not allowed [visitors]. When a death occurred, the method of burial and protocols are without social mixing…. [Because of this], people hesitated.”

He added that COVID-19 patients remain at home, going to the hospital only when the situation deteriorates.[165]

Women were reportedly among the least likely to use a community COVID-19 isolation center. An administrator at an NGO in Idlib explained that “The nature of the services and centers designated for corona do not pay much attention to privacy, especially for women, which makes them less likely to obtain the service.”[166] A sexual and reproductive health care administrator working for an NGO remarked, “If I lived in Idlib and I got corona and they told me that I have to go to the isolation center for 15 days, I would not go. My husband will divorce me, and my family will abandon me. We know the stories about what happens in Syria and what it means for a woman … a young or old girl, married or unmarried, to sleep 15 days outside her home.”[167]

Vaccine skepticism has reportedly intensified the impact of the current wave of the virus in Idlib, where there have been reports of between 1,000 to 1,500 infections a day.[168] Even among medical staff in Idlib, there was mistrust in the vaccine, leading some organizations to threaten not to renew the contracts of unvaccinated doctors.[169] A former field doctor who now works in an administrative role for a health NGO in Idlib reported that acceptance of the vaccine has improved over time in Idlib and that larger segments of the population have turned out to receive vaccines.[170] However, the Türkiye Health Cluster, which provides cross-border aid to areas of Idlib and Aleppo outside the control of the Syrian government, reports that the vaccinated population is only around 1 percent.[171] The WHO reports that, as of November 12, 2021, 176,360 people in northwest Syria had received at least one dose of vaccine.[172]

COVID-19 in Turkish-Controlled Areas

An NGO administrator based in Gaziantep observed that, from the onset of COVID-19, health workers “started monitoring deaths at home…. There are a good number of people who died at home, and this is a serious matter that may indicate the inability of people to reach health facilities during that period.”[173] Syrians who suspect that they have COVID-19 may avoid isolation centers for multiple reasons, leaving response programs and resources underutilized. An administrator in a health facility in A’zaz explained, “Despite the establishment of these hospitals and projects, most people are treated at home.”[174] In Turkish-controlled areas, COVID-19 patients do not have access to quarantine centers and ventilators due to limited availability. An administrator in a health facility indicated that, instead, patients requiring ventilators must travel to other governorates in northern Syria or to areas controlled by the Syrian government to receive treatment.[175]

The change in donor focus reportedly triggered a shift in staffing, as physicians from other specialties were taking positions in COVID-19 centers. A respondent in A’zaz noted, “We have isolation centers, but we don’t have infectious disease specialists,” adding, “These centers are often run by a general or thoracic doctor, or a doctor with a completely unrelated specialty.”[176]

Respondents indicated that news about the vaccine reaches people via social media platforms laden with conspiracy theories, which may have contributed to the low demand for vaccines in Turkish-controlled areas.[177] A doctor from A’zaz described the vaccine hesitancy, saying, “There was a two-month vaccination campaign in the north. Not many people accepted it, but it was implemented.”[178]

“People used to tell me [while I was giving a] training, ‘Should we be afraid of this small virus, or the chemical weapons above our heads, or the bombing? Bashar [President Assad] has tried everything on us. Let the virus come and kill us all.’”

Health care worker in Idlib

Social Behavior and Lack of Adherence to Public Health Guidelines

The populations of northern Syria, though divided among different regions of control, reportedly share a widespread desensitization to the danger of COVID-19. A respondent observed that social distancing and mask wearing is practically nonexistent, explaining that some people believe that the virus is no more deadly than the flu or common cold.[179] However, others report that the population has become numb to the threat of COVID-19 after a decade of horrific, and often indiscriminate, violence.

A health care worker in Idlib recounted, “People used to tell me [while I was giving a] training, ‘Should we be afraid of this small virus, or the chemical weapons above our heads, or the bombing? Bashar [President Assad] has tried everything on us. Let the virus come and kill us all.’”[180] An administrator from a health facility in Deir Ezzor remarked that throughout northern Syria, fatalism has set in: “People have forgotten that there is such a thing as corona during the past months. He who dies, dies, and he who gets better, gets better.”[181]

An administrator at a health services NGO in Idlib ascribed public complacency about COVID-19 to early successes in combatting the disease following dire warnings from the heath sector.[182] A health care provider in Idlib opined that the impact of the first wave of COVID-19 was less severe than anticipated, in part because of restrictions on entering Idlib governorate that helped curb the spread.[183] In Idlib, the early warning and vaccination teams responded quickly and effectively to the initial wave of cases. The health services administrator remembered,“In March 2020, the College of Medicine launched a wide campaign, visited homes, distributed brochures, and gave lectures in mosques. Many organizations carried out a big campaign against this illness.”[184] Campaigns like these, led by medical schools and NGOs, have been effective in lieu of mandatory COVID-19 prevention and isolation policies, which were not enforced in either northwest or northeast Syria and led to a lack of engagement from local communities.[185]

Legal and Policy Analysis

Syria, Türkiye, and the non-state armed groups in northern Syria are bound by international legal obligations to provide for the right to health and to humanitarian assistance for populations under their control. In addition to their obligations under international human rights law, discussed below, both Syria and Türkiye were among the countries that voted to adopt the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,[186] which includes the right to life (Article 3) and the right to a standard of living adequate for “health and well-being,” including medical care (Article 25.1). Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) also recalls the ethical obligations of donors and the humanitarian organizations that carry out their work to promote the right to health by providing assistance without discriminatory effect. This includes the duty to provide care to the most vulnerable, including women and the disabled.

The Right to Humanitarian Assistance

The parties to the conflict in Syria must allow for delivery of humanitarian aid in areas under their control and refrain from impeding access to health care. Civilians in areas of armed conflict have a right to receive humanitarian aid, including medical and other supplies essential to survival.[187] International humanitarian law allocates primary responsibility for meeting civilian needs to the state or party that controls the territory in which the civilians are located.[188] Multiple UN Security Council resolutions have indicated that organized armed groups which exercise effective control over territory and carry out administrative and public functions are responsible for protecting the rights of civilians in the territories they control. [189] For example, in Sudan, Resolution 1574 called on the Justice and Equality Movement and the Sudanese Liberation Army – both opposition groups holding territory – to uphold human rights; in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Resolution 1376 called on all parties, particularly in “territories under the control of the rebel groups,” to end human rights violations and Resolution 1417 identified the opposition group Rassemblement Congolais pour la Democratie-Goma, as the “de facto authority” responsible for ending human rights violations in the territory it holds.[190] In short, a non-state armed group that is organized and exercises administrative control over territory, as exists in northwest Syria, has the same duties as a government party to the conflict.[191]

If a government or another party with the responsibility to meet essential civilian needs fails to do so, humanitarian organizations and other states can offer to provide relief, as long as they are impartial in character and give priority to those in most urgent need of care.[192] The affected state must consent to delivery of humanitarian assistance to civilian populations in need. However, a state may not withhold consent arbitrarily.[193] The Security Council may also adopt a binding decision permitting UN agencies and their humanitarian partners to deliver aid. In Syria, such a decision was made in 2014, when Security Council Resolution 2165 first authorized UN humanitarian agencies and their partners to deliver humanitarian assistance to Syria across conflict lines – meaning from territory held by one party into another – and through border crossings with Iraq, Jordan, and Türkiye. These UN crossings did not require the consent of the Syrian government or other parties to the conflict.[194] Seven years after establishing the four border crossings, Russia, with the assistance of China, has used its veto power on the Security Council to reduce the UN authorization to one border crossing, Bab al-Hawa.

International Human Rights Law

The Syrian government is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR),[195] which provides for the right to life (Article 6) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), [196] which provides for the right to health (Article 12).[197] The Turkish government is party to the ICCPR and the ICESCR,[198] in addition to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities,[199] and therefore may be responsible under international law for upholding these rights in the two enclaves in northern Syria which it controls.[200] Non-state actors must prevent violations of the right to health to the extent that they exercise territorial and administrative control.

The Right to Health

Critically, the health systems described in this report fail to meet the standards established for the right to health as described in the ICESCR. The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) has stated that health is a fundamental human right indispensable for the exercise of other human rights. The right to health imposes four essential standards on health care services: availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality.[201] The CESCR monitors the implementation of the treaty and has stated that parties must ensure, at the very least, “minimum essential levels” of each right, including the right to health.[202] Health care systems in each area discussed in this report are highly fragmented to a degree that effectively violates Article 12(d), “The creation of conditions which would assure to all medical service and medical attention in the event of sickness.” Instead, services are clustered in one geographic area, while most areas are effectively deprived of service because of the difficulties with transportation and security.

The ICESCR requires signatories to “to take steps” to the maximum of their available resources to achieve progressively the full realization of the right to health (Article 2.1). Regardless of the resources available, however, the “non-discrimination” clause of the ICESCR (Article 2.2) applies, providing that the rights in the covenant “will be exercised without discrimination of any kind as to race, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”[203] The Committee has clarified that this means that health facilities, goods, and services must be “accessible to everyone without discrimination.”[204] The inequities described in this report within each area and compared with other parts of Syria overall make clear that health care is currently provided unequally, to the extent it is being provided at all. For example, in 2019, pro-government governorates received greater health care staffing support than those in areas retaken by the government.[205] In 2020, the annual WHO survey listed seven public hospitals in Deir Ezzor governorate, but over half are nonfunctioning, and the other three are considered “partially functioning.”[206] In Raqqa, three of the four public hospitals are partially functioning, and one is nonfunctioning, while in al-Hasakah province, the only fully functioning hospital is in al-Qamishli, a city in an area known to support the Syrian government. In Idlib, all four public hospitals are considered nonfunctional.[207] A different 2020 WHO report on public health centers in Syria found that 65 percent of the less than 6 percent of health centers that were “fully functioning” were located in Aleppo, the majority of which is controlled by the Syrian government.[208] In comparison, the majority of health centers in every government-controlled governorate, except for Dara’a, were “fully functioning,” and less than 13 percent of health centers were “non-functioning.” Of the total number of non-functioning health centers in Syria (553), 73 percent were in northern governorates. In northern Syria, the Syrian government’s apparent policy of impeding delivery of humanitarian assistance and its documented attacks on health care facilities and personnel have effectively limited access to health care, as has the Turkish government’s patchwork of regulations.

Conclusion

Physicians for Human Rights’ (PHR) research on the health systems of non-government-controlled regions of Syria reveals extreme disparities in health care among northwest Syria, northeast Syria, and Turkish-controlled areas. The right to health is being violated by the failure of all those providing aid – including humanitarian actors and donors – to ensure minimum standards for health care in crises.