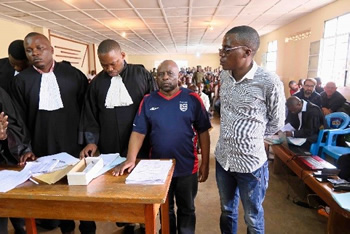

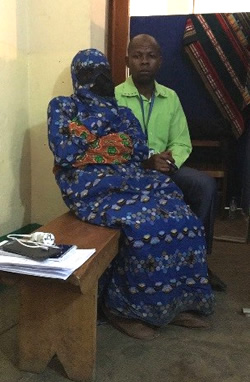

Witnesses are cloaked head to toe to protect their identities in court.

Photo: Physicians for Human Rights

Cloaked from head to toe to shield her identity, the witness was led into the makeshift court room and seated behind a screen. Out of sight of the 18 defendants, she addressed the court.

“Batumike’s militia killed my husband,” she said, referring to defendant Frederic Batumike, a local lawmaker. “They attacked me and I lost consciousness. When I woke up, I found my husband with machete injuries all over his body and no head. They had decapitated him.”

The witness, identified only by the codename T4, was one of dozens expected to take the stand in a landmark sexual violence trial in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). On Friday, November 9, proceedings began in the small village of Kavumu, where prosecutors allege Batumike and an armed militia led a campaign of violence that terrorized the community for four years. The trial is being held in what is known as a mobile court so that the proceedings can take place in the affected community.

Among the defendants’ purported crimes: the kidnapping, rape, and mutilation of 46 girls, some as young as eight months old. Since the first days of the investigation, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) has worked in partnership with doctors, nurses, and psychologists, as well as military investigators, police, and lawyers, to help gather evidence and prosecute these crimes. (Read more about the case and PHR’s role here.)

While efforts to protect the identities of witnesses and victims may seem routine in these types of cases, the director of PHR’s Program on Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones, Karen Naimer, said such measures are seldom taken in Congolese courts.

“In earlier cases, victims were sometimes forced to show their faces to alleged perpetrators or stand before spectators and defendants,” Naimer said. “Not only did that put survivors at incredible risk, it also risked tainting their testimony because the presence of their alleged assailant could intimidate or silence them. Speaking out about crimes of sexual violence already requires an immense amount of courage and has the potential to re-traumatize survivors. Forcing them to do so without any protection is dangerous and imperils the justice process.”

Before the proceedings began, PHR and its local and international partners – including TRIAL International, whose representatives are also in the court room every day – pushed the judges in the Kavumu case to allow witnesses to testify without having to stand before the defense (read all of those recommendations here). The court allowed PHR to provide voice modification devices and said that witnesses and victims could use codenames instead of their real names.

“Congolese authorities and members of the UN peacekeeping force in the country have taken great strides to protect these important proceedings,” said PHR’s police and justice expert, Georges Kuzma, who has been attending every day of the trial so far. “Still, there are perhaps hundreds of supporters of Batumike and his alleged militia members in the community. Those who have spoken out against him have been murdered. These witnesses are bravely testifying in the hopes that such rampant impunity can be halted after so many years of uncertainty and terror.”

For the witness identified as T4, she knows firsthand about such reprisals. Her husband was a local community activist who spoke out against Batumike’s alleged crimes. Prosecutors say that is why, in March 2016, he was murdered. And, despite the safety precautions, an informant who testified against the defendants this past week was threatened outside the court at one point. Military judges warned they would accept no such intimidation during the course of the trial.

At every step of the way, PHR has worked to ensure that sound forensic and physical evidence was properly collected, documented, stored, and entered into the record. During the first week of trial, the panel of judges introduced bags of evidence collected by PHR-trained military investigators. Both Batumike and his wife were asked to answer for their possession of weapons and other incriminating evidence prosecutors presented to the court.

“Good evidence. Good forensics. Good police and medical work. These are the kinds of practices that can bring justice, and that’s why we’ve trained hundreds of health professionals, police, judges, and community activists in these best practices across Congo,” said PHR’s Naimer. “We and our partners believe that staunching sexual violence requires accountability. The survivors deserve at least that much, and trials like this one send a message to the powerful that they are not immune to the rule of law.”

Indeed, as a local lawmaker, Batumike had prosecutorial immunity, but in a show of increasing intolerance for lawlessness in Congo, his fellow lawmakers chose to lift his immunity before the trial. PHR’s Kuzma said that gives a degree of confidence to those who courageously testify against those in power.

“On Wednesday, a witness became very emotional while she was speaking,” Kuzma said. “But with the rigorous protection measures in place, she said she was motivated to speak and provide whatever information she could that would be helpful in bringing justice. That’s an incredible breakthrough.”

The trial is expected to last until late December. Follow day-to-day developments of the trial on our Twitter feed, review photos on our Facebook page, and, for more information, contact media@phr.org.