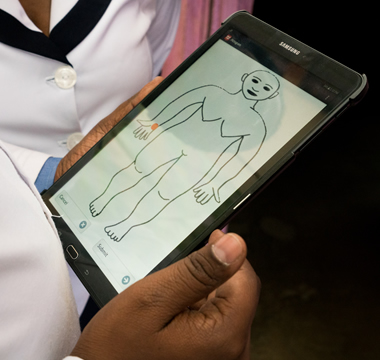

PHR’s award-winning MediCapt mobile app enables doctors, clinical officers, and nurses to collect, store, and securely share forensic medical evidence in cases of sexual violence. After field-testing the app in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, PHR’s Program on Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones launched MediCapt in Kenya earlier this year. Kenya Program Associate Suzanne Obanda Kidenda shares her experiences introducing this innovative tool.

Why is MediCapt necessary in Kenya?

Nearly 40 percent of Kenyan women and girls aged 15 and above have suffered sexual and gender-based violence – and that figure triples and quadruples during periods of conflict and upheaval. We saw this after the elections in 2007, 2013, and again in 2017. In the three months following the 2007 elections, for example, at least 900 women, girls, men, and boys suffered sexual and gender-based violence – and we know that this number is just a fraction of the total because of the difficulty for victims to access health care facilities, which is where this data was collected. But even those survivors who do report face real challenges in seeing their cases get to court. This is where we believe MediCapt can make a real difference.

What do you see as MediCapt’s potential impact and promise in fighting sexual violence in your country?

Often, the doctors, clinical officers, and nurses who examine survivors of sexual violence collect incomplete information that can’t be used as evidence to prosecute the cases in court. Sometimes, clinicians skip sections of the Kenyan Post-Rape Care (PRC) form – the standardized medical-legal form used to document medical evidence of sexual violence – because they feel they lack the expertise to fill it out. Then there’s the problem of lack of resources. Some facilities don’t have PRC forms at all. Sometimes there’s no police car – or, if there is a vehicle, there’s not enough fuel in the tank – to collect or deliver evidence. Many facilities lack secure storage to keep their documentation and evidence safe from tampering, loss, or destruction. And, finally, lack of coordination and distrust among the professionals involved – clinicians, police officers, lawyers, and judges – means that, often, this vital information does not get transmitted across the sectors. MediCapt can help overcome many of these challenges.

How does MediCapt work?

MediCapt is an android application that converts the Post-Rape Care form into a digital format, which allows it to be accessed via a mobile device like a tablet or cell phone. The app prompts the clinician examining the survivor to fill out all the form’s fields – this ensures that there’s a complete electronic record of the patient’s history, report of the incident, injuries, and examinations performed. Using MediCapt’s photo capture function, clinicians are also prompted to take forensic photographs of their patients’ physical injuries. All this information is uploaded to the Cloud and can then be accessed in a secure and efficient way by other professionals working on the case, such as police, lawyers, and judges. By making sure that evidence is properly collected, safely preserved, and securely transmitted, we’re helping to give survivors a better chance at justice. And, with the addition of the GeoMaps feature, MediCapt can help analyze trends and patterns of sexual violence across Kenya. This data collection will be very useful in advocating for better laws and measures to combat sexual violence and support survivors.

What was your strategy for introducing MediCapt in Kenya?

Before the official introduction of MediCapt, we carried out assessments in four counties in Kenya where PHR works in order to evaluate where we might best integrate the app into local medical and legal systems. This involved assessing existing mobile technology, electronic systems at health facilities, and the strength of the referral pathways for sexual violence survivors. We settled on the Naivasha Sub-County Referral Hospital as the pilot site because of the capacities, skills, and resources within the institution and the possibility of partnering with the county government. What was also important was that there was already good cross-sectoral coordination between the police, health care workers, and judiciary in the area following our training workshops over the last few years.

Within Naivasha hospital, we selected 13 individuals who would pilot MediCapt. These were drawn from all the departments that attend to survivors of sexual violence: casualty (emergencies), out-patient, youth-friendly center, comprehensive care center, and the records department. They’ve named themselves the “Pioneers” of MediCapt! Since our initial training in January, these pioneers have been practicing with the app and are giving us valuable feedback on how to improve it.

What are some of the challenges that you are encountering in launching MediCapt?

One concern is not to increase the workload of the practitioners using MediCapt – we want to make sure that we’re easing the burdens related to the current practice of using paper forms to document sexual violence cases. This means making sure that MediCapt works smoothly with the other record-keeping activities at the hospital so other departments can use the information our pioneers are collecting without requiring them to duplicate their work.

Another concern the pioneers have raised is about taking forensic photographs for use in court. Photographic evidence for sexual offences is not currently widely presented in court cases, but the law does allow clinicians to submit photographs as part of their own medical documentation – something which MediCapt solves for.

One other challenge has been with the constant updates that need to be made to the app. The collaborative design approach we use with MediCapt means that we are constantly receiving recommendations for improvement. This is definitely a plus, but it also requires a quick turnaround to ensure the testing process continues seamlessly.

What are the Kenyan partners who are pioneering MediCapt saying about the app?

We’ve received a lot of great feedback. Much of it is focused on the unique features that MediCapt adds to forensic documentation – such as photographs, GeoMaps, and locking forms once they have been submitted to keep them from being tampered with.

You’ve been a key player in the launch of MediCapt in Kenya. How do you feel about the project and its potential?

I thought I knew all that MediCapt was about, but through this piloting period I have gained a deeper appreciation of what the app has to offer and its potential for Kenya.

MediCapt is a game changer, not only in the documentation of sexual offences to support investigations and prosecution, but also because the information that MediCapt collects can be used to improve services in the institutions where it is used. And by analyzing trends and patterns in the data, the Kenyan government can use MediCapt to allocate resources or even for rapid response and emergency preparedness. It also has great potential to improve coordination and collaboration across the various sectors. I echo the sentiments of the pioneers who are currently testing MediCapt: I can’t wait for it to finally go live!