Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and the Cardozo Law Institute in Holocaust and Human Rights (CLIHHR) are pleased to provide this submission in response to the International Criminal Court (ICC) Office of the Prosecutor’s (OTP) Call for Updates of the OTP 2014 Policy Paper on Sexual and Gender-Based Crimes (2014 Policy Paper). The 2014 Policy Paper was a groundbreaking step forward in articulating the commitment of the OTP to prioritize redress for sexual and gender-based crimes (SGBC) and address barriers to achievement of this vision. This, along with the 2022 Policy on the Crime of Gender Persecution, establishes the commitment of the OTP to adopt a gender-competent perspective and to prioritize accountability for SGBC. As an organization committed to addressing SGBC, PHR and CLIHHR offer this submission to suggest how the 2014 Policy Paper can be updated and further developed to articulate key principles in addressing SGBC occurring during and outside of conflict.

What Constitutes a High-Quality, Comprehensive Medico-Legal Affidavit in the United States Immigration Context?

This fact sheet summarizes the findings of the first published multi-sectoral consensus-building exercise on medico-legal affidavits in the U.S. immigration context. Medico-legal affidavits are underpinned by an expert medical evaluation which can objectively contextualize trauma and corroborate accounts of abuse; they are a critical component in immigration proceedings where somebody is seeking protection on the basis of said trauma or abuse. However, the lack of existing validated guidelines has led to inconsistencies in clinical evaluations’ format, structure, and content, causing confusion for practitioners and adjudicators alike. Drawing on expertise from adjudicators, attorneys, and clinicians, this Physicians for Human Right (PHR) research therefore aimed to pinpoint what experts viewed as the most crucial aspects of medico-legal asylum evaluations and their accompanying affidavits. By using a modified Delphi approach to collect and synthesize expert opinions, a consensus was reached on the defining features of a high-quality, comprehensive evaluation. The study identified seven key areas that were most agreed upon by participants, which serve as a foundation for future efforts to standardize and enhance the overall quality and consistency of medico-legal reports.

Voicing Our Plight

Using Photovoice to Assess Perceptions of Mental Health Services for Survivors of Sexual Violence in Kenya

Executive Summary

Background

Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) is a global health crisis. More than 730 million women worldwide have experienced physical or sexual violence at least once in their lifetime.[1] In Kenya, the Demographic and Health Survey of 2022 showed that 34 percent of women and girls[2] surveyed reported having experienced physical violence at least once in their lifetime and 13 percent reported having experienced sexual violence, with many of these cases going unreported to authorities.[3] SGBV has profound impacts on a survivor’s physical and mental health.[4] Access to mental health care is a major challenge for survivors of sexual violence.[5]

In Kenya, 34 percent of women and girls aged 15-49 years surveyed have experienced physical violence at least once in their lifetime and 13 percent have experienced sexual violence, with many of these cases going unreported. SGBV has profound impacts on survivors’ physical and mental health, and access to mental health care is a major challenge for survivors of sexual violence.

Physicians for Human Rights’ Program on Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones began working in Kenya in 2011 to confront impunity for sexual violence committed during the unrest that followed the 2007 national elections.

From 2020 to 2022, PHR worked with partners, including the Survivors of Sexual Violence Network in Kenya (SSVKenya) convened by the Wangu Kanja Foundation, to address challenges faced by survivors. These included medical-legal documentation of the mental health impacts of sexual violence and access to quality mental health services in Kenya. The project, supported by the Comic Relief & UK Aid Mental Health Programme, aimed to enhance the capacities of health professionals and institutions in Kenya to provide post-rape mental health care and to forensically document the mental health impacts of sexual violence, as well as to strengthen the legal and policy framework on mental health care in Kenya.

This assessment arose out of PHR’s interest in understanding the impact of these interventions and related advocacy from the perspective of survivors of sexual violence, themselves. To ensure the voices of survivors remained at the heart of the assessment, PHR partnered with SSVKenya, an advocacy coalition comprised of survivors of sexual violence in Kenya.

Methodology

To conduct the assessment, PHR and SSVKenya jointly identified 10 survivors of sexual violence from across Nairobi who lived in areas that benefitted from the intervention, were active in SSVKenya, and were engaged in their communities as activists, human rights defenders, and volunteers helping other survivors access health services.

The assessment team selected Photovoice – a participatory action research (PAR) methodology through which community members document their experiences using photography – as well as voice recordings for this assessment.

The use of this methodology reflected a deliberate choice to empower survivors and mitigate the risk of re-traumatization that is inherent in traditional, interview-driven methodologies. The assessment team included self-selected survivors who were motivated to document issues important to them and their community and three PHR staff members. Using this methodology, survivors were equal partners in the assessment.[9],[10]

The assessment team selected Photovoice – a participatory action research (PAR) methodology through which community members document their experiences using photography. Using this methodology, survivors were equal partners in the assessment.

Findings

The assessment team took a total of 223 photos during a one-week period in October and November 2022 representing their experiences accessing mental health services in Nairobi. These photos were accompanied by a total of 99 WhatsApp voice notes.

Analysis of these materials, conducted by the assessment team and the survivor-collaborators, showed that survivors perceived gaps in the availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality (AAAQ) of mental health services. As the AAAQ are the essential elements to realizing the right to health, they provide a powerful framework to understand sexual violence-related mental health services from a rights-based perspective.[12]

Availability

Survivors said mental health services for survivors of sexual violence are often unavailable in their communities, due to closed facilities, missing staff, or infrastructure challenges. They said there is minimal prioritization of mental health care services in general, and specifically of services targeting survivors of SGBV and other vulnerable groups.

Accessibility

Survivors identified difficulties accessing mental health services across Nairobi, with transportation a major challenge. They also experienced challenges accessing private facilities, primarily due to the high cost of mental health services and medication.

Acceptability

Survivors felt that many services being offered were not acceptable for their particular needs, including lack of private spaces for counselling sessions. They feared breaches of confidentiality and others learning about their history of sexual violence. They also noted challenges in accessing survivor-centered care, including the fact that providers multitasked during care.

Survivors said mental health services for survivors of sexual violence are often unavailable in their communities, due to closed facilities, missing staff, or infrastructure challenges.

Quality

Survivors frequently reported challenges related to the quality of services being offered. They shared their doubts regarding the skill level of health professionals on providing mental health services and how to engage with survivors of sexual violence. Survivors saw challenges in the implementation of existing policies and standards ensuring quality care in their areas.

Kenya has a clear obligation under national laws and policies to address these gaps and provide high quality, accessible, acceptable, and available mental health care. The Constitution of Kenya affirms that “every person has the right to the highest attainable standard of health.”[13] The Mental Health Amendment Act’s 2022 revisions state that survivors of sexual violence are entitled to access affordable mental health services in Kenyan health facilities.[14] The Sexual Offences Act Medical Regulations operationalize the provisions of the Sexual Offences Act and provide a legal foundation for access to no-cost post-rape care, which includes mental health services (i.e., counselling) for survivors of sexual violence.[15] The National Guidelines on Management of Sexual Violence in Kenya[16] provide guidance on the survivor-centered implementation of health services for survivors, including mental health services. This solid legal framework provides a robust platform from which Kenya’s national and local governments can implement existing laws to realize the right to mental health of survivors of sexual violence. Despite the strong domestic legal and policy landscape for the provision of mental health care for survivors of sexual violence, there is a gap in the implementation of these policies.

Finally, the government of Kenya, as a party to international human rights treaties and obligations – including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and the Protocol to the African Charter on the Rights of Women in Africa (the Maputo Protocol) – is obligated to ensure that all sexual violence-related care (including mental health care) is provided in line with the AAAQ framework and should address obstacles to the realization of these standards.

Survivors perceived gaps in the availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality of mental health services. They said there is minimal prioritization of mental health care services in general, and specifically of services targeting survivors of SGBV and other vulnerable groups.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This assessment not only deepened understanding of the perceptions of survivors of sexual violence about the challenges they face in accessing mental health services, but it also prioritized the engagement of survivors in advocating for change in their communities. This enables the results of this assessment to contribute to action and advocacy efforts. Finally, this assessment shows that Photovoice, as an example of a participatory research and evaluation method, can be a powerful tool to ensure that survivors of sexual violence can remain in the center of assessments, research, and evaluations conducted to understand their experiences.

Based on the assessment’s results, PHR and the Survivors of Sexual Violence Network in Kenya offer the following recommendations:

To all stakeholders, including national and county governments and civil society organizations:

▪ Ensure that measures are taken to engage survivors’ perspectives and ensure that their voices are included, listened to, and heard in processes to improve mental health services for survivors. This includes ensuring that survivors of sexual violence are able to engage at public meetings at the sub-county, city, national and other levels. Stakeholders must proactively engage survivor networks, such as the Survivors of Sexual Violence Network in Kenya, when developing laws, policies, and programs meant for survivors. Finally, stakeholders should leverage participatory methods to engage survivors to integrate survivor priorities in the design of polices and legislation.

▪ Engage in reparations and transitional justice processes to ensure the inclusion of mental health care and services for survivors of sexual violence, as part of survivor-centered and holistic reparations.

To the Nairobi City County Government:

▪ Prioritize the establishment of the Mental Health Council as per the provisions of the Mental Health Amendment Act. The council should include experts in mental health and representatives of survivors’ groups to ensure that the specific mental health needs of survivors of sexual violence are represented on the council. They should be required to maintain a register of all private mental health facilities operating within their counties and submit these to the Mental Health Board annually. They should also be mandated to inspect these facilities and report their findings to the Mental Health Board for remedial action that may be necessary.

▪ Allocate more financial resources to mental health service provision and increase the number of staff offering mental health services. Dedicate additional funding and conduct annual capacity development for all health care providers on the provision of mental health services to ensure all are equipped with the skills to provide trauma-informed, survivor-centered initial mental health support, forensic psychological documentation, and referrals as needed.

▪ Strengthen the integration of mental health service provision into routine and primary health care, including ensuring that primary health care providers can identify and refer survivors of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) to mental health services.

▪ Fully implement the National Guidelines on Management of Sexual Violence in Kenya at health facilities that provide post-rape care, with particular emphasis on provisions of the guidelines that enhance the survivor-centered aspects of mental health-related service delivery, including ensuring privacy.

▪ In line with the Sexual Offenses Act Medical Regulations and The Nairobi City County SGBV Management and Control Bill, allocate county health funds to guarantee no-cost post-rape care and affordable mental health care for priority populations.

▪ Ensure that mental health providers are available to provide services during the hours of clinic operation.

▪ Train and engage community mental health workers to offer appropriate first-line mental health services to and referrals for survivors of sexual violence. This should include new and formal programs with survivors’ networks to provide peer support and engagement with other survivors.

▪ Conduct public education campaigns to create awareness on the importance of mental health care, psychosocial support, and the mental health impacts of SGBV in order to address community level stigma, discrimination, and negative attitudes related to mental health care and treatment that prevent many survivors from accessing services. This should include dissemination of information on the mental health services that are available to survivors, which clinics offer mental health services, hours of operation, and which services are free of charge.

▪ Develop new programs to ensure mental health services are more accessible to survivors of sexual violence. This should be done by providing transportation or transportation stipends to ensure survivors can return for mandated follow-up counselling sessions. Develop programs to offer home-based, online, virtual, or phone-based counselling services or at the community level to reduce the physical, logistical, and financial barriers to accessing mental health services.

▪ Ensure that health facilities and locations for mental health services are accessible and user-friendly. Additionally, provide wheelchairs, ramps, and signs that indicate where facilitates are located, and update publicly available information about when service providers will be available to provide services.

▪ Ensure that the privacy of survivors of sexual violence seeking mental health is protected at all public facilities, in line with the National Guidelines on Management of Sexual Violence. This should include access to private and separated treatment rooms where survivors can access services without fear of disclosure or interruption.

To the Ministry of Health:

▪ Prioritize the provision of trauma-informed, survivor-centered mental health services for survivors of SGBV, including, specifically, mental health counseling and access to psychological assessments, where needed, to capture critical evidence of sexual violence.

▪ Further develop and implement guidelines and protocols for the health sector on the provision of comprehensive mental health services to SGBV survivors. Specifically, expedite the adoption of the rules and regulations that will operationalize the Mental Health Amendment Act 2022, including ensuring access to mental health care without discrimination.

▪ Design, fund, and implement comprehensive training, campaigns, and awareness-building on the importance of mental health care for survivors of sexual violence for all health care workers, as well the scope and nature of legal obligations and national and international standards on the provision of such care. Develop standardized training materials and continuous medical education courses for health care workers to provide survivor-centered, trauma-informed mental health services and psychosocial to support survivors of sexual violence. This training should be conducted simultaneously with the development/implementation of facility and community health protocols to support the management of SGBV survivors.

▪ Through the National Treasury, allocate resources to county governments for the training, recruitment, and deployment of well-trained mental health service providers.

▪ Ensure the availability of funds at the county level and undertake monitoring to ensure survivors can meaningfully access no-cost services for post-rape care, including psychological assessments and mental health care, as mandated by the Sexual Offenses Act Medical Regulations. Increase the budgetary allocation to mental health services to, at a minimum, the recommended WHO standards at the national level.

▪ Undertake and fund additional assessments, research, and data collection on the impact of sexual violence on survivors’ mental health to be used to increase the accessibility, availability, acceptability, and quality of mental health services for survivors of sexual violence.

▪ Implement accountability processes at the national and county levels to monitor and evaluate the provision of high-quality, acceptable, available, and accessible mental health care for survivors of SGBV, without discrimination, and provide redress and remedy where survivors face barriers in accessing such care, including investigations by the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights where there are suspected violations of rights related to the mental health care of survivors.

▪ Ensure targeted implementation of the existing laws, including the Constitution of Kenya (article 43) and the Mental Health Amendment Act, to ensure that the right to the highest attainable standard of health is realized.

To Donors:

▪ Continue to support survivor’s groups and programs that provide mental health care for survivors, including capacity development for service providers on mental health care, survivor-centered approaches, and psychological documentation.

▪ Support programs that use participatory approaches to engage survivors in assessments, research, and monitoring and evaluation.

To organizations conducting assessments, research, and monitoring and evaluation with survivors of sexual violence:

▪ Use participatory research and evaluation methods, such as Photovoice, to leverage their utility as powerful tools that ensure survivors of sexual violence remain in the center of assessment, research, and monitoring and evaluation conducted with the aim of understanding survivor experiences and producing recommendations that will result in changes in spaces that matter most to survivors.

Acknowledgements

This assessment was written by staff members of Physicians for Human Rights’ (PHR) Program on Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones, Thomas McHale, SM, deputy director, Suzanne Kidenda, senior program officer- Kenya, and Olivia Dupont, MPH, program manager; and Millicent Akinyi, Jane Alfayo, Mercy Etole, Grace Kamau, Beatrice Karore, Margaret Kinyua, Ashura Mciteka, Diana Mushiyi, Lorraine Ong’injo, and Bonila Sisia, members of the Survivors of Sexual Violence in Kenya Network.

The assessment benefitted from review by PHR staff, including Erika Dailey, MPhil, director of advocacy and policy, Christian De Vos, JD, PhD, director of research and investigations, Lindsey Green, MA, senior program officer, Karen Naimer, JD, LLM,

MA, director of programs, Naitore Nyamu-Mathenge, LLM, MA, Kenya head of office, Dr. Ranit Mishori, MD, MHS, FAAFP, senior medical advisor, Payal Shah, JD, director, Program on Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones, Kevin Short, deputy director of media and communications, and Saman Zia-Zarifi, JD, LLM, executive director. The assessment was strengthened through external review by Donna Shelley, MD, MPH. It was reviewed, edited, and prepared for publication by Claudia Rader, MS, PHR senior communications consultant, with assistance from Samantha Peck, PHR executive and program associate and board liaison.

PHR would like to thank Rutgers International for sharing curriculum materials that were adapted and used for Photovoice trainings in this project. This innovative assessment would not have been possible without the generous support of the Comic Relief & UK Aid Mental Health Programme.

Above all, PHR is grateful to partners from the Survivors of Sexual Violence in Kenya Network (SSVKenya) who shared their time, stories, and photographs with us, and for the partnership with SSVKenya, whose members continue to passionately represent the priorities of survivors in Kenya and beyond.

Citations and Endnotes

[1] “Facts and Figures: Ending Violence against Women,” UN Women – Headquarters, https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures.

[2] This statistic only includes women and girls aged 15-19 who were usual members of (or slept at the night before) households sampled as part of the Kenya Demographic and Health survey, 2022.

[3] Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Health/Kenya, National AIDS Control Council/Kenya, Kenya Medical Research Institute, and National Council for Population and Development/Kenya, 2023, Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2022, Rockville, MD, USA: Available at https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR143/PR143.pdf.

[4] “WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women,” n.d.

[5] Nikram Patel, Neerja Chowdhary, Atif Rahman, and Helen Verdeli, 2011, “Improving Access to Psychological Treatments: Lessons from Developing Countries,” Behaviour Research and Therapy 49 (9): 523–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.012.

[6] Survivor-collaborator quote, Data collection period October 28 – November 4, 2023.

[7] Survivor-collaborator quote, Data collection period October 28 – November 4, 2023.

[8] Survivor-collaborator quote, Data collection period October 28 – November 4, 2023.

[9] M. Candace Christensen, 2017, “Using Photovoice to Address Gender-Based Violence: A Qualitative Systematic Review,” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, July, 152483801771774, https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017717746.

[10] “Using Photovoice to Address Gender-Based Violence: A Qualitative Systematic Review.”

[11] Survivor-collaborator quote, Data collection period October 28 – November 4, 2023.

[12] Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, “The Right to Health Fact Sheet,” https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/ESCR/Health/RightToHealthWHOFS2.pdf.

[13] Constitution of Kenya 2010, Article 43(1). n.d., http://kenyalaw.org/kl/index.php?id=398.

[14] “The Mental Health Act,” Kenya, 2022.

[15] “Sexual Offences Act Medical (Treatment) Regulations,” Kenya, 2020.

[16] Nairobi, Ministry of Health, 2014, National Guidelines on Management of Sexual Violence in Kenya.

Through Our Lens: Visualizing Perceptions of Mental Health Services for Survivors of Sexual Violence in Kenya

Survivors of sexual violence in Kenya have the right to mental health care, yet services are widely lacking. For those who do attempt to find the mental health care they need, what do they experience?

This is the guiding prompt for images and reflections from survivors of sexual violence in Nairobi, Kenya. Using a participatory methodology called Photovoice, a group of women set out to document their journey to seek out and access mental health care. The resulting collection of images reveals significant gaps in the availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality of mental health services being offered to survivors in Nairobi. Read more about this project

These photos ask us to consider how surviving sexual violence might change how a person looks at their community when using mental health services, where even daily scenes can take on new meaning: Crowded public transportation may induce anxiety; trash in a flooded lot evokes a sense of despair. For one survivor, even a malfunctioning streetlight is a reminder that women in Nairobi are at risk of attacks on the streets. Others described health facilities where survivors receive mental health services in areas that are not private, to show that even the services that are available do not always make survivors feel comfortable. In some of the images, survivors have recreated typical interactions, such as with strangers on the street, or in conversation with mental health professionals, to illustrate experiences of social stigma, isolation, and lack of privacy. Yet the images also convey hope. Women standing together in solidarity, or friends gathered together to talk about health care. Even smooth paving leading to a health clinic is an encouraging sign.

These survivors in Kenya were motivated to document issues important to them and their community. Taken together, their images serve as a reminder that survivors of sexual violence in Kenya have the right to mental health care, and the government of Kenya is obligated to provide it. Explore the galleries below or read the assessment “Voicing Our Plight: Using Photovoice to Assess Perceptions of Mental Health Services for Survivors of Sexual Violence in Kenya”

Ashura Mciteka

Beatice Karore

Bonila Sisia

Diana Mushiyi

Grace Kamau

Lorraine Ong’ijo

Millicent Akinyi

About the Project

In Kenya, 34 percent of women and girls aged 15-49 years surveyed have experienced physical violence at least once in their lifetime and 13 percent have experienced sexual violence, with many of these cases going unreported. SGBV has profound impacts on survivors’ physical and mental health, and access to mental health care is a major challenge for survivors of sexual violence.

Physicians for Human Rights’ Program on Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones began working in Kenya in 2011 to confront impunity for sexual violence committed during the unrest that followed the 2007 national elections. From 2020 to 2022, PHR worked with partners, including the Survivors of Sexual Violence Network in Kenya (SSVKenya) convened by the Wangu Kanja Foundation, to address challenges faced by survivors. These included medical-legal documentation of the mental health impacts of sexual violence and access to quality mental health services in Kenya.

The project, supported by the Comic Relief & UK Aid Mental Health Programme, aimed to enhance the capacities of health professionals and institutions in Kenya to provide post-rape mental health care and to forensically document the mental health impacts of sexual violence, as well as to strengthen the legal and policy framework on mental health care in Kenya.

This assessment arose out of PHR’s interest in understanding the impact of these interventions and related advocacy from the perspective of survivors of sexual violence, themselves. To ensure the voices of survivors remained at the heart of the assessment, PHR partnered with SSVKenya, an advocacy coalition comprised of survivors of sexual violence in Kenya.

Submission from PHR and the Cardozo Law Institute in Holocaust and Human Rights on International Criminal Court Office of the Prosecutor’s Policy on Children

Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and the Cardozo Law Institute in Holocaust and Human Rights (CLIHHR) are pleased to provide this submission in response to the International Criminal Court (ICC) Office of the Prosecutor’s (OTP) call for suggested changes to build upon, and renew, the 2016 OTP Policy on Children. As organizations committed to addressing sexual and gender based crimes (SGBC) faced by children, PHR and CLIHHR offer this submission to suggest how the Policy on Children can be further developed to articulate key principles in addressing crimes occurring at the intersection of age and gender, and to incorporate practical tools, international standards, and reference materials to implement these principles in practice.

Human Rights Must Guide Pandemic Responses: 7 Lessons from COVID-19

Today marks a new chapter in the fight against COVID-19, as the Public Health Emergency (PHE) expires in the United States. Similarly, on May 5, 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the end of the Public Health Emergency of International Concern, downgrading COVID-19 from an emergency to an “ongoing health issue” with a need to focus on longterm management.

While we may be moving out of an acute, emergency phase of the pandemic, people are still dying from COVID-19 in staggeringly large numbers (more than 1000 deaths in the U.S. alone each week). As we can expect to see more incidents of infectious diseases in the future, we must not be complacent, especially when it comes to protecting vulnerable communities.

These transitions also represent a new chapter for Physicians for Human Rights (PHR). For the past year, I have helped lead PHR’s work around the COVID-19 pandemic. As the PHE comes to an end, I want to reflect on our engagement with the emergency over the last three years, to describe PHR’s hopes to continue its work going forward, and to highlight lessons to take forward in preparation for the inevitable next pandemic.

1. Vaccines saved lives. Vaccine equity would have saved even more.

The global bio-pharmacological response to COVID-19 was extraordinary, with tests, treatments and vaccines made at record speeds. International scientific information-sharing and collaboration among scientists, researchers, and health experts were likewise unprecedented. However, nationalism and vaccine hoarding led to many preventable deaths, widened inequities, and prolonged the pandemic.

PHR underscores the importance of centering human rights and equity in both pandemic response and any public health emergency. At the heart of vaccine inequity lies decades of underinvestment in global health and health infrastructure and a general lack of available or affordable access to pharmacotherapies and technologies.

PHR has continuously worked to highlight vaccine equity through various forms of advocacy including letters, data, webinars, press releases, and calls for accountability, as well as working to ensure that marginalized communities – such as those in immigration detention – are included in vaccine allocation and rollout. We joined other organizations calling for waiving intellectual property rules and urging the World Trade Organization to ease patents for COVID-19 tests and treatments. PHR has closely followed the Pandemic Accord (WHO CA+) negotiations and welcomes the inclusion and ongoing discussion of intellectual property, publicly funded goods, and the human rights responsibilities of governments and institutions. At the 77th World Health Assembly in May 2024 we hope to see an accord that has been strengthened rather than weakened, and one that creates a mechanism that protects the right to life for everyone, everywhere.

2. Protecting communities begins with protecting health workers.

In the early days of the pandemic, health workers throughout the world faced enormous challenges responding to the pandemic in clinical settings and at home. Health workers have faced verbal and physical abuse, stigmatization, the scourge of pervasive dis-misinformation, all while struggling to protect themselves both physically and mentally. From lacking adequate personal protective equipment, to needing greater support to combat burnout and increase their resilience, health workers have been tested like never before. PHR has advocated to support and uplift the voices of health workers through research, collaboration, resources, toolkits, and guidance both in the United States and internationally.

Protecting health workers and public health officials must be a core feature of preparing health systems for future emergencies. It is clear that if we cannot protect health workers and uplift their expertise, no one is safe.

3. Health and social impacts fall disproportionately on historically marginalized communities.

Throughout the world, the COVID-19 pandemic spotlighted and worsened existing inequities in access to health and demonstrated persistent threats to international human rights, including the right to equality and non-discrimination, the right to life, and the right to free movement. Understanding the unequal burdens and violations of human rights that have disproportionately impacted certain groups is vital and necessary.

Fear around COVID-19 helped fuel racism, discrimination and xenophobia globally. People of color, immigrants and undocumented workers – all of whom are often overrepresented in public-facing, “essential” jobs – were more likely to be exposed to COVID-19. Similarly, they were disproportionately impacted by inadequate safety net services, poor access to paid sick leave, and unaffordable or inaccessible health. We have seen how governments can weaponize health emergencies against ethnic minorities, refugees and asylum seekers, and impose unnecessary and disproportional limits on travel and border crossing.

In the United States, under the guise of public health, an order known as Title 42 allowed the government to expel children and adults seeking refuge in the US, despite the lack of scientific evidence to support it. PHR has advocated against this rule since it’s implementation and has filed several amicus briefs in federal courts. PHR also studied the impact of expulsions on health and human rights, rallied thousands of medical professionals, repeatedly called for an end to border expulsions, and continuously condemned the ongoing use of Title 42 expulsions. As Title 42 expires today, along with the Public Health Emergency, PHR will continue to monitor the impact of new Biden Administration policies on those seeking asylum. Public health cannot be weaponized to serve political agendas.

4. Misinformation and disinformation is deadly.

The world experienced a flood of constant COVID-19 mis- and disinformation, leading to health harms, erosion of public trust in science, and political battles over public health For example, areas of the United States exposed to television programming that downplayed the severity of the pandemic saw greater numbers of cases and deaths, likely because people ignored or dismissed public health recommendations. A recent analysis found that across the United States, and between January 2021 and April 2022, there were at least 318,000 vaccine-preventable COVID-19 deaths.

Scientists and health workers are important and trustworthy voices; they must be protected whenever navigating any pandemic or public health emergency. Mis- and disinformation attacked the integrity of health workers. In response, PHR has worked to empower physicians and health workers to fight back against health conspiracies. We have publicly supported empowering state medical boards to take action and discipline physicians who undermine public health and endanger their communities.

5. Civil society remains underrepresented at decision making tables.

Civil society organizations (CSOs) are crucial voices for representing the needs of communities and ensuring inclusion and accountability; they also have some of the most experience in advancing social protection and the application of public health measures. These valuable voices were underrepresented during the world’s COVID-19 response and continue to be inadequately engaged in preparedness and prevention discussions.

PHR has called for ongoing and additional inclusion of CSOs in the WHO Pandemic Accord. PHR has advocated for voices of civil society through open letters on participation and key priorities, engagement in high-level meetings, and a more holistic lens centering human rights at the United Nations General Assembly, with partners at the People’s Vaccine Alliance and The Civil Society Alliance.

6. COVID-19 fueled a “parallel pandemic” of gender-based violence.

Sheltering in place came with a rise of domestic and intimate partner violence globally, especially affecting women and children. The United Nations estimated that “6 months of lockdowns could result in an additional 31 million cases of gender-based violence.”

PHR has explored the impact of COVID-19 on clinical care and services for sexual and gender-based violence in the United Kingdom and Kenya and called for health worker education, health system responsibility, and multisectoral collaboration. We have likewise explored the unique challenges of navigating women’s health services during the pandemic, and how particular communities are impacted, including refugee communities and those living in conflict zones.

Future pandemic and public health emergency responses need to adopt a more robust gender lens. Sexual and gender-based violence services must be deemed essential, alongside comprehensive family planning and reproductive services.

7. Accountability is vital to address future pandemics.

To genuinely participate in adequate preparedness, prevention and response, governments, institutions, and organizations must critically review and evaluate decisions made during COVID-19 and be transparent about their findings.

PHR has sought to improve state accountability for inadequate COVID-19 responses by joining partner organizations in calling on global leaders to pledge that the mistakes of this pandemic not be repeated. To that end, PHR has supported the strategic litigation of the Open Society Justice Initiative, which recently filed a complaint before the European Committee of Social Rights (ECSR) against Bulgaria for failing to prohibit discrimination and failing to protect health during their COVID-19 vaccination rollout.

Governments, global health organizations and health-related funders have a duty and moral imperative to engage wholeheartedly in prevention and preparedness, and to uphold human rights in the process.

No One Could Say: Accessing Emergency Obstetrics Information as a Prospective Prenatal Patient in Post-Roe Oklahoma

Executive Summary

In the wake of the 2022 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Oklahoma residents are currently living under three overlapping and inconsistent state abortion bans that, if violated, impose severe civil and criminal penalties on health care providers. Exceptions to these new laws, enacted around the Supreme Court’s overturning of its 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade, are extremely limited and confusing to health professionals and potential patients alike. Because the exceptions drafted by legislators are often conflicting and use non-medical terminology, they sow confusion around what kinds of care and procedures health care providers can legally offer when a pregnancy threatens a person’s health or life. These challenges, combined with the significant penalties under these bans, constitute a situation of “dual loyalty”: health professionals are forced to balance their obligation to provide ethical, high-quality medical care against the threat of legal and professional sanctions. The decision to provide emergency medical care risks becoming a legal question – determined by lawyers – rather than a question of clinical judgment and the duty of care to the patient – determined by health care professionals.

In light of the extensive anti-abortion legal framework newly in place in the state, Oklahoma offers an important insight into the potential effects of near-total abortion bans on pregnant patients and the clinicians who care for them. While bans such as Oklahoma’s have already severely limited access to abortion medication or procedures, reproductive justice advocates have raised concerns that it is especially unclear what care remains accessible in practice in cases of obstetric emergencies. Accordingly, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), Oklahoma Call for Reproductive Justice (OCRJ), and the Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR) have examined Oklahoma as a case study to investigate two key questions:

- Do hospitals have policies and/or protocols that govern decision-making when pregnant people face medical emergencies, and are pregnant people in Oklahoma able to receive information on these policies, if they do exist?

- If information is provided to prospective patients on hospital policies and/or protocols related to obstetric emergency care, what is the content and quality of that information?

To study these questions, PHR, OCRJ, and CRR used a “simulated patient” research methodology, in which research assistants posed as prospective patients and called hospitals that provide prenatal and peripartum care across the state of Oklahoma to ask questions related to emergency pregnancy care.

Not a single hospital in Oklahoma appeared to be able to articulate clear, consistent policies for emergency obstetric care that supported their clinicians’ ability to make decisions based solely on their clinical judgement and pregnant patients’ stated preferences and needs.

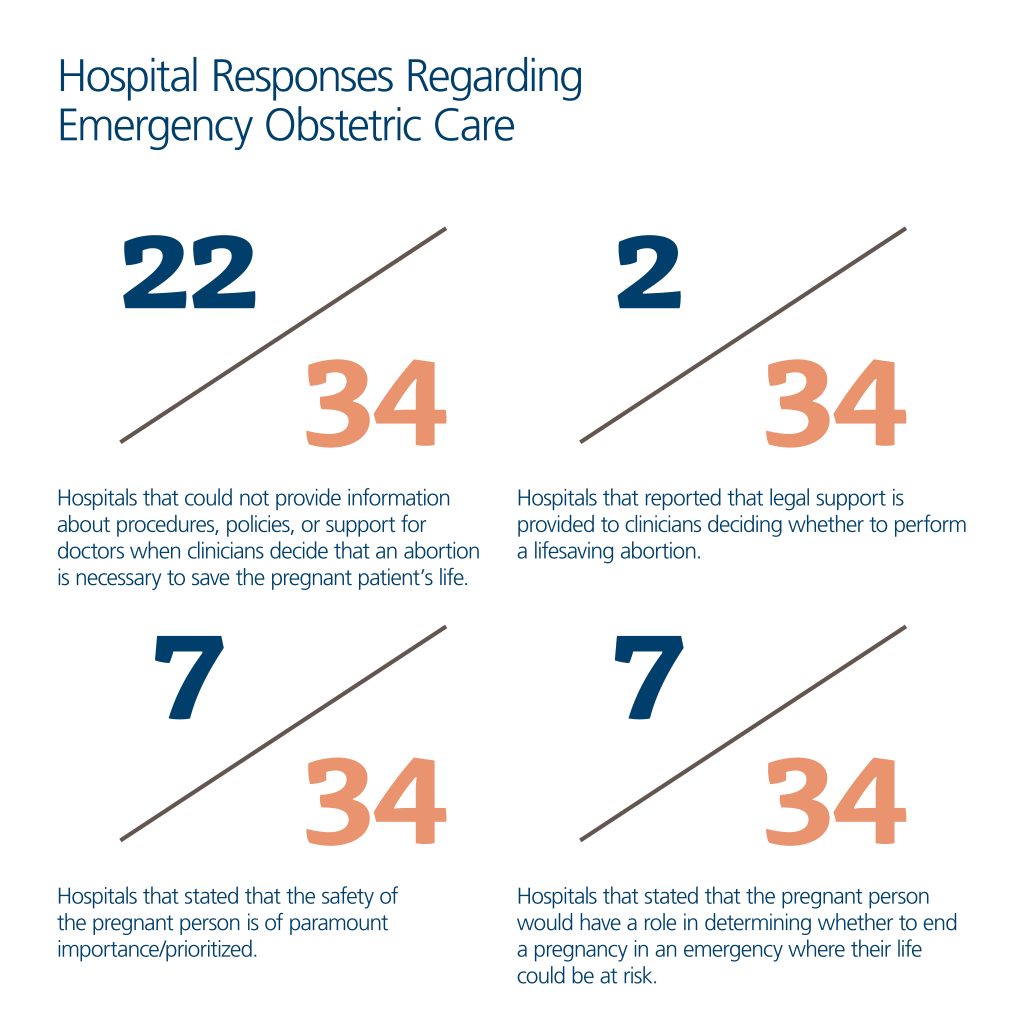

The results of this research are alarming. Not a single hospital in Oklahoma appeared to be able to articulate clear, consistent policies for emergency obstetric care that supported their clinicians’ ability to make decisions based solely on their clinical judgement and pregnant patients’ stated preferences and needs. Of the 34 out of 37 hospitals offering obstetric care across the state of Oklahoma that were reached, 65 percent (22 hospitals) were unable to provide information about procedures, policies, or support provided to doctors when the clinical decision is that it is necessary to terminate a pregnancy to save the life of a pregnant patient; only two hospitals described providing legal support for clinicians in such situations. In 14 cases (41 percent), hospital representatives provided unclear and/or incomplete answers about whether doctors require approval to perform a medically necessary abortion. Three hospitals indicated that they have policies for these situations but refused to share any information about them; four stated they have approval processes that clinicians must go through if they deem it necessary to terminate a pregnancy; and three stated that their hospitals do not provide abortions at all. (Oklahoma hospitals that are affiliated with an Indigenous nation were excluded from the study; because they operate under federal oversight, it is unclear how the Oklahoma bans impact them.) Some examples of the information the simulated patients received include:

- One hospital representative claimed: “If the situation is truly life-threatening, decisions will be made,” without explaining how those decisions would be made or by whom.

- Another hospital representative stated that, “[i]t is tricky because of state laws, but we will not let the mom die.”

- In one circumstance, the caller was told that a pregnant patient’s body would be used as an “incubator” to carry the baby as long as possible.

- At one hospital, a staff member put the simulated caller on hold and, after consulting with a hospital physician, told the caller, “Nowhere in the state of Oklahoma can you get an abortion for any reason,” even though the bans have exceptions.

In sum, in response to questioning, hospitals provided opaque, contradictory, and incorrect information about when an abortion is available; lacked clarity on criteria and approval processes for abortions; and offered little reassurance to patients that their survival would be prioritized or that their perspectives would be considered.

Hospitals provided opaque, contradictory, and incorrect information about when an abortion is available; lacked clarity on criteria and approval processes for abortions; and offered little reassurance to patients that their survival would be prioritized or that their perspectives would be considered.

The study’s findings demonstrate that despite apparently good-faith efforts from most hospital representatives, callers could not access clear and accurate information about the care they would receive if facing a pregnancy-related medical emergency at any given institution. Moreover, the information they received was often confusing – at some hospitals, callers received conflicting information from separate staff within the same hospital. These findings raise grave concerns about the ability of a pregnant person in Oklahoma – and the other 12 states with similar, near-total abortion bans – to receive clear, sufficient, and necessary information to make informed decisions about their medical care, as well as the ability of such patients to receive medically-necessary treatment. Callers also found that some hospital administrations, in an effort to comply with state laws, imposed restrictive policies on medical personnel that would impede their ability to provide prompt and effective care for pregnant patients with medical emergencies, including in cases of miscarriage.

One hospital representative claimed: “If the situation is truly life-threatening, decisions will be made,” without explaining how those decisions would be made or by whom. In one circumstance, the caller was told that a pregnant patient’s body would be used as an “incubator” to carry the baby as long as possible.

Health care providers face a similarly untenable situation under the current abortion bans. The criminalization of abortion denies access to abortion for pregnant people under most circumstances, and narrow exceptions such as “only to save the life” of the pregnant patient lead to confusion, uncertainty, and fear, both for pregnant people and for the hospitals and health care providers that care for them. Clinicians face severe criminal and civil penalties, such as the loss of their medical licenses and long prison sentences, if prosecutors and state legislators disagree with their medical decision-making. In light of these obstacles, pregnant people are faced with the frightening possibility that they will be unable to receive science-informed, patient-centered, and ethical medical care should they face an obstetric emergency.

These results reflect how Oklahoma’s abortion bans threaten the health and well-being of pregnant people and violate their human rights. These violations include individuals’ rights to life, health, equality, information, freedom from torture and ill-treatment, and to exercise reproductive autonomy. These findings further affirm what has been recognized by the World Health Organization: that the criminalization and penalization of abortion care – even with an exception for medical necessity – is fundamentally inconsistent with evidence-based, ethical, and patient-centered health care.

Oklahoma’s abortion bans threaten the health and well-being of pregnant people and violate their human rights.

Given these findings, PHR, OCRJ, and CRR make the following topline recommendations: (full recommendations can be found below)

To the Oklahoma Legislature:

- Repeal Oklahoma’s abortion bans and decriminalize abortion.

- Ensure that health care services for pregnant people and all Oklahomans are accessible and of good quality.

To Oklahoma’s Hospitals and Health Care Professionals:

- Speak out against laws criminalizing abortion or otherwise restricting access to abortions, including during obstetric emergencies.

- Build knowledge and awareness of professional recommendations and guidance for providing abortion services.

To State and National Medical Associations:

- Publicly condemn abortion bans and continue to speak out against the dual loyalty impacts of abortion bans, including citing evidence of how such laws undermine ethical obligations and professional duties of care.

To the Federal Government:

- Enact and implement national laws and policies that ensure rights and remove barriers to abortion care and maternal health care.

Introduction

In June 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturning almost 50 years of legal precedent and eliminating the federal constitutional right to abortion. This decision marked the first time in American history that the Supreme Court took away a right it had recognized as fundamental to personal liberty. As U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland noted, abortion has been “an essential component of women’s liberty for half a century – a right that has safeguarded women’s ability to participate fully and equally in society.”[1]

Oklahoma was one of many states that sought to ban abortion in the lead-up to – and in the wake of – the Dobbs decision. It now has three overlapping abortion bans in effect, each with different elements and exceptions. A fourth ban with criminal penalties was enacted in 2022, but that law was struck down by the Oklahoma Supreme Court in March 2023. Providing someone with an abortion or assisting them in accessing an abortion in Oklahoma remains illegal, except in narrowly and ambiguously defined medical emergencies and circumstances that threaten a pregnant person’s life.[2] State legislators in Oklahoma continued to push legislation in 2023 that creates further legal risk for those involved in receiving and providing care for pregnant people in cases of emergencies.

In light of the many anti-abortion laws enacted in recent years in the state, Oklahoma offers an important view into the potential effects of near-total abortion bans on pregnant patients and the clinicians who care for them, both in Oklahoma and in other states with similar bans. Using a “simulated patient” research methodology, this study examined whether pregnant people could access information about the care they might receive at Oklahoman hospitals that provide prenatal and peripartum care, should they face a medical emergency – and, if they could, the quality and clarity of that information.

The Effect of Dobbs on Abortions Provided Due to a Medical Emergency

In the wake of the Dobbs decision, a number of states swiftly began instituting or enforcing laws that nearly or entirely ban abortion with narrow exceptions, many with criminal penalties for health professionals who provide abortion care. As of April 2023, 13 states have instituted and are enforcing abortion bans.[3] For example, Arkansas bans abortions at all stages of pregnancy, with no exemptions except to “save the life” of a pregnant person.[4] Mississippi similarly bans abortion with narrow exceptions to “save the life” of a pregnant person or in cases of rape or incest that are reported to law enforcement.[5] South Dakota bans abortions with exceptions to “preserve the life” of a pregnant person.[6] The impact of these laws will fall hardest on people who already face discriminatory obstacles to health care: Black, Indigenous, and other people of color, people with disabilities, people in rural areas, young people, undocumented people, and those with limited financial resources.[7]

Many of these states’ laws contain language that does not reflect precise or accurate medical terminology, particularly in describing valid legal exemptions to the bans. Of particular concern, as of February 21, 2023, four out of the 13 states with abortion bans include exemptions phrased along the lines of, “except when necessary to save the life of the mother,” with no further detail, explanation, or other exemptions.[8] Four other states use this language and add only one additional exception written along the lines of, “to prevent severe, permanent damage to major organs or bodily functions.”[9]

In practice, the language used for exceptions to abortion bans is open to interpretation. This may seem like a positive measure – giving deference to clinicians in applying laws. However, against a backdrop of criminalization and inconsistent exceptions that do not utilize medical language, such exceptions only sow more fear and confusion and potentially make clinicians reluctant to take steps to provide necessary medical care to patients.[10] For instance, what circumstances or indicators of medical severity qualify as an emergency that threatens a pregnant person’s life? How imminent or severe must the threat be? What are appropriate mechanisms and policies that health systems must enact to provide support, guidance, and legal protection for health professionals faced with these time-sensitive and critical clinical decisions? To what extent are or should a patient’s own views and tolerance for risk be considered in such decision-making?

These narrow, vague exceptions to criminalization place medical professionals providing care for pregnant patients in the position of balancing their duty to provide ethical, high-quality medical care against the threat of legal and professional sanctions. In other words, physicians must weigh concerns for their patients’ health with the recognition that their actions in medical emergencies could leave them vulnerable to criminal charges, with potential penalties as severe as 15 years in prison, thousands of dollars in fines, and loss of their medical licenses. Such conflicts constitute dual loyalty, a situation in which health care workers “find their obligations to their patients in direct conflict with their obligations to a third party … that holds authority over them” – in this case, state governments.[11]

Physicians must weigh concerns for their patients’ health with the recognition that their actions in medical emergencies could leave them vulnerable to criminal charges, with potential penalties as severe as 15 years in prison, thousands of dollars in fines, and loss of their medical licenses.

This concern has quickly proven true. American Medical Association President Jack Resneck, Jr. has decried the “chaos” into which health care has been thrust since the Dobbs decision, describing physicians as “caught between good medicine and bad law,” struggling to “meet their ethical duties to patients’ health and well-being, while attempting to comply with reckless government interference in the practice of medicine that is dangerous to the health of … patients…. Physicians and other health care professionals must attempt to comply with vague, restrictive, complex, and conflicting state laws that interfere in the practice of medicine.”[12]

American Medical Association President Jack Resneck, Jr. has decried the “chaos” into which health care has been thrust since the Dobbs decision, describing physicians as “caught between good medicine and bad law.”

Providers have shared concerns about confusion related to medical emergencies and the incompatibility of various state abortion laws with caring for patients facing such emergencies. Tennessee has an abortion ban with no exceptions, although it allows providers to raise a defense in a prosecution that an abortion was medically necessary. Seven hundred doctors signed on to a letter calling on legislators to reconsider the ban for a variety of reasons, including because “it forces health care providers to balance appropriate medical care with the risk of criminal prosecution.”[13] Similarly, Louisiana doctors who are operating under several bans attested that “[f]ear of punishment aligned with lack of clarity on how this law will be enforced can lead to devastating consequences for Louisiana women as well as moral distress for the clinicians who care for them and have taken the Hippocratic oath to do no harm.”[14] Common pregnancy complications may present situations where providers are too cautious in providing necessary care because they are concerned that a patient is not sick enough, such as if a patient presents with preterm premature rupture of membranes (i.e., when the amniotic sac surrounding the fetus prematurely ruptures), potentially serious infections, or with other preterm complications that require emergency medical intervention and are likely to result in pregnancy loss or long-term harm to the pregnant person’s health and reproductive capacity.[15]

The bans also have concerning implications for the medical management of miscarriages (threatened, incomplete, or complete). It is estimated that up to 26 percent of pregnancies end in miscarriage, many of which require medical intervention to avoid health emergencies such as infection or hemorrhage.[16] Media reports reflect that the unclear language employed by many states in their abortion bans is causing confusion and hesitation among health professionals when handling miscarriages that require medical management, such as the surgical removal of a nonviable fetus and cases in which there is still fetal cardiac activity.[17] This is because treatments for miscarriage are the same as those used to provide an abortion.[18] These reports also demonstrate a growing sense of fear among patients about the care they might receive at health care facilities should they present with common symptoms such as bleeding or pain, as well as anxiety surrounding future pregnancies.

Indeed, prospective patients face the daunting task of trying to determine what these laws mean for the care they can expect to receive in hospitals in states with abortion bans. The answers to these crucial questions may vary considerably across health care institutions. Thus, pregnant people in these states struggle to access necessary information about how their own possible obstetric emergencies might be handled at different hospitals to determine their best options for maternity care, what treatment options are legal, and whether they can receive information in advance to better guide their decision-making.[19] Would a hospital they are considering require multiple layers of bureaucracy to secure approvals to terminate a pregnancy – such as oversight committees or requirements for second physicians to agree that their life is sufficiently at risk – that could create delays, leading to their death? Moreover, can patients trust the hospitals to support clinicians who prioritize their lives in the face of a life-threatening medical emergency? Without receiving clarity on these crucial questions, pregnant people struggle to make informed decisions about where to seek care.

To help answer these questions, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), Oklahoma Call for Reproductive Justice (OCRJ), and the Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR) have examined Oklahoma as a case study to investigate two key questions:

- Do hospitals in Oklahoma have policies and/or protocols that govern decision-making when pregnant people face medical emergencies, and are pregnant people in Oklahoma able to receive information on these policies, if they do exist?

- If information is provided to prospective patients on hospital policies and/or protocols related to obstetric emergency care, what is the content and quality of that information?

The following report describes the research methodology for this study, its findings, relevant legal and ethical standards, and recommendations based on what the research revealed.

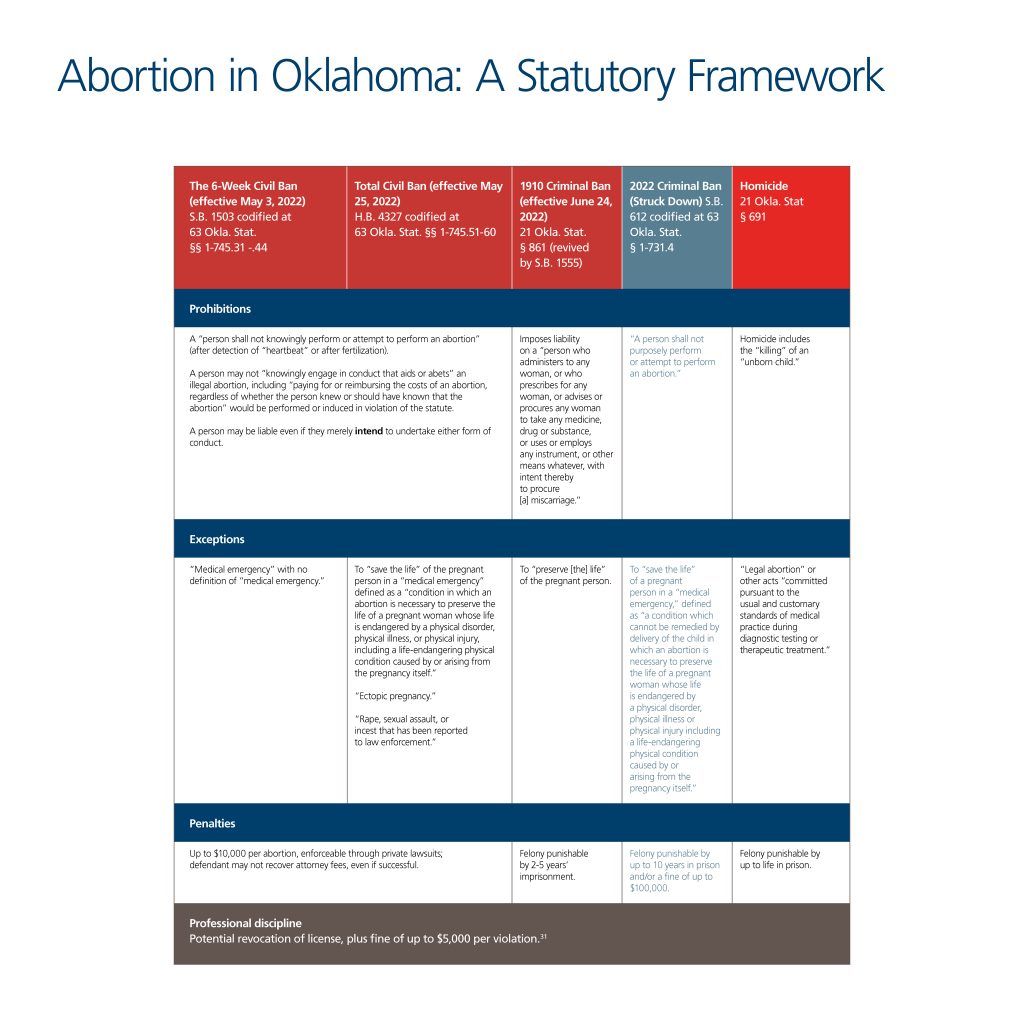

Legal Background

At the time of this writing, Oklahoma has three overlapping abortion bans (two civil and one criminal) in effect as well as a homicide statute that could be applied to the provision of abortion. A fourth ban with criminal penalties was enacted in 2022, but that law was struck down by the Oklahoma Supreme Court in March 2023. These laws have inconsistent prohibitions and penalties, resulting in a dangerous lack of clarity around their application. In particular, the exceptions in the laws permitting abortion in cases of medical emergencies conflict, which has resulted in significant confusion around when abortions are permitted in the face of a medical emergency.

On March 21, 2023, the Oklahoma Supreme Court issued a 5-4 decision upholding the constitutionality of Oklahoma’s 1910 pre-Roe ban on abortion but striking down a 2022 criminal ban on the grounds that its narrow medical exceptions provision violated the “inherent right of a pregnant woman [under the Oklahoma Constitution] to terminate her pregnancy when necessary to preserve her life.” The opinion did not address still-pending challenges to two other civil bans, which both include “medical emergency” language that was found to be unconstitutional in the Court’s decision. The Oklahoma Supreme Court stated that it “would define this inherent right to mean: a woman has an inherent right to choose to terminate her pregnancy if at any point in the pregnancy, the woman’s physician has determined to a reasonable degree of medical certainty or probability that the continuation of the pregnancy will endanger the woman’s life due to the pregnancy itself or due to a medical condition that the woman is either currently suffering from or likely to suffer from during the pregnancy. Absolute certainty is not required; however, mere possibility or speculation is insufficient.” This decision could ultimately provide greater comfort to health care providers treating patients experiencing emergent conditions, but given the other two civil bans still in effect (one of which has the same medical exception deemed insufficient by the Oklahoma Supreme Court), confusion is unlikely to be assuaged at present. At publication, it remains unclear how hospitals will react to the decision.

Legislators have not been able to articulate how these bans operate together. An investigative journalist contacted all 42 lead sponsors and cosponsors of the four recent abortion bans and found that none could “answer basic questions about the bans’ enforcement.”[20] Oklahoma’s attorney general acknowledged confusion about the application of these bans in guidance to law enforcement that was issued on August 31, 2022.[21] The guidance is not binding, and it does not clearly remedy the conflicts, nor does it address the two civil bans.[22]

The four recent abortion bans took effect one after another starting just before the Dobbs decision was released on June 24, 2022. First, Oklahoma enacted two abortion bans modeled after Texas S.B. 8, allowing private citizens to bring lawsuits against those who provide abortions or assist those seeking abortions. Then the state enacted two more abortion bans with criminal penalties. Three remain in effect:

- S.B. 1503 (“6-Week Civil Ban” or “Heartbeat Law,” effective May 3, 2022): The 6-Week Civil Ban prohibits physicians from “knowingly” providing an abortion after “detect[ing] a fetal heartbeat” or if the physician “failed to perform a test to detect a fetal heartbeat.” [23] The law creates a civil enforcement mechanism by which any person not affiliated with the state or local government “may bring a civil action against any person” who performs a prohibited abortion, “knowingly” aids or abets a prohibited abortion, or intends to engage in these activities.[24]

- H.B. 4327 (the “Total Civil Ban,” effective May 25, 2022): The Total Civil Ban shares a similar civil enforcement scheme with the 6-Week Civil Ban, but it applies from the moment of “fertilization.” [25]

- 21 Okla. Stat. § 861 (the “1910 Criminal Ban,” effective June 24, 2022): The 1910 Criminal Ban was an old law blocked after Roe v. Wade was decided, which was revived when “the Attorney General certifie[d] that … [t]he United States Supreme Court … overruled in whole or in part Roe … and … Casey.” [26] Oklahoma’s attorney general issued this certification on June 24, 2022, the same day Dobbs was decided. The statute prohibits an abortion at any point during a pregnancy.[27]

- S.B. 612 (the “2022 Criminal Ban,” struck down by the Oklahoma Supreme Court on March 21, 2023): The 2022 Criminal Ban prohibited abortion at any stage of pregnancy, with more extreme criminal penalties than the 1910 Criminal Ban.[28]

Oklahoma’s homicide statute could also be used to prosecute providers of abortion because the law considers the “killing of an unborn child” to be a homicide, punishable by up to life in prison.[29] Further, medical licensing boards are empowered to discipline clinicians and take action to suspend or revoke their licenses based on any violations of state law.[30]

Oklahoma’s homicide statute could also be used to prosecute providers of abortion because the law considers the “killing of an unborn child” to be a homicide, punishable by up to life in prison.

The resulting statutory framework includes inconsistent definitions, intent provisions, exceptions, and penalties (see table below).

Understanding the scope and nature of permitted exceptions for abortion is particularly challenging under these laws. The Total Civil Ban permits abortion only when necessary to preserve a person’s “life in a medical emergency,” defined as a “condition in which an abortion is necessary to preserve the life of a pregnant woman whose life is endangered by a physical disorder, physical illness, or physical injury, including a life-endangering physical condition caused by or arising from the pregnancy itself,” although the 2022 Criminal Ban was struck down because of an almost identical “medical emergency” exception.[32]

The other abortion bans in effect, however, do not discuss exceptions based on specific medical emergencies. The 6-Week Civil Ban contains an exception for medical emergencies but does not define what counts as a medical emergency.[33] The 1910 Ban, which has now been upheld by the Oklahoma Supreme Court, similarly includes no mention of specific medical emergencies, as it only permits abortions to “preserve [the] life” of the pregnant person.[34] Meanwhile, Oklahoma’s homicide statute criminalizes the killing of an “unborn child,” except for a “legal abortion” or other acts “committed pursuant to the usual and customary standards of medical practice during diagnostic testing or therapeutic treatment.”[35] Further, the Total Civil Ban explicitly exempts care for an “ectopic pregnancy” and allows abortion for pregnancies resulting from “rape, sexual assault, or incest that has been reported to law enforcement.”[36] None of the other bans expressly carves out such exemptions.

Under these provisions, physicians cannot know when they are legally permitted to end a pregnancy. In a “medical emergency” that merely “endangers” the life of the patient, must they wait until the patient’s life is in immediate jeopardy? What criteria must be used to determine that this threshold is met? For example, are ectopic pregnancies (a dangerous medical condition in which a fertilized egg implants outside of the uterine cavity, typically in a fallopian tube) clearly exempted? The Oklahoma bans fail to answer these vital questions.

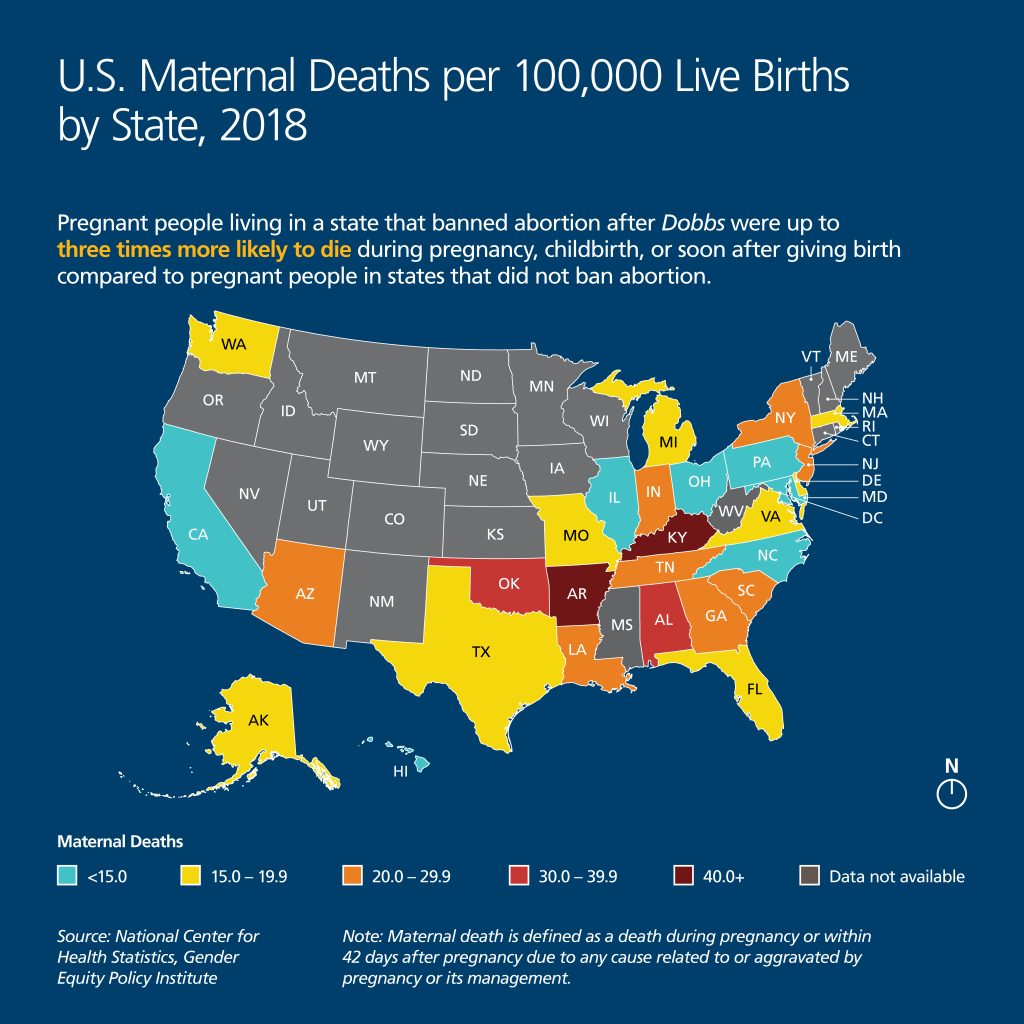

Impacts on Health

The medical literature is clear that criminal abortion bans are linked to a range of negative physical and mental health outcomes for pregnant people, in the United States and around the world. The unworkability of even an exception in the context of medical emergencies particularly implicates maternal mortality and morbidity. Constraining physicians from providing necessary care in medical emergencies is extremely dangerous for patients. The United States already has the highest maternal mortality rate of all high-income countries, with the U.S. maternal death rate further increasing over the COVID-19 pandemic, from 20.1 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2019, to 23.8 in 2020, to 32.9 in 2021.[37] Moreover, “For every U.S. woman who dies as a consequence of pregnancy or childbirth, up to 70 suffer hemorrhages, organ failure or other significant complications, amounting to more than 1 percent of all births,” according to data from ProPublica and NPR.[38] This crisis in U.S. maternal health outcomes disproportionately impacts people from Black, Indigenous, and low-income communities, who consistently face the greatest risks during their prenatal, pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum phases linked to historic discrimination and inadequate access to quality health care. [39]

The medical literature is clear that criminal abortion bans are linked to a range of negative physical and mental health outcomes for pregnant people, in the United States and around the world. Constraining physicians from providing necessary care in medical emergencies is extremely dangerous for patients.

According to the Gender Equity Policy Institute, pregnant people living in a state that banned abortion after Dobbs were up to three times more likely to die during pregnancy, childbirth, or soon after giving birth compared to pregnant people in states that did not ban abortion.[40] This continues a trend in the United States wherein states that support reproductive health services, including by expanding Medicaid and supporting access to abortion and contraception, have lower maternal mortality rates than states that have restricted access to reproductive health care.[41] These disparities will likely increase as abortion bans continue to take effect around the country, with people of color among the most likely to suffer.[42]

Oklahoma exemplifies this alarming trend. Black and Indigenous residents of Oklahoma face significantly higher rates of maternal mortality than white residents. Moreover, Oklahoma “persistently ranks among the states with the worst rates” of maternal deaths in the United States, and maternal deaths in Oklahoma have “increased in recent years.”[43] According to the Oklahoma State Department of Health, from 2004 to 2018, Black pregnant women in Oklahoma suffered “more than 2.5 times the rate of deaths compared to the white population,” a statistic the Oklahoma Maternal Mortality Review Committee called an “alarming disparity.”[44] The Department further concluded that Indigenous pregnant women in Oklahoma “have experienced up to 1.5 times the rate of deaths when compared to white women over the years.”[45]

According to the Gender Equity Policy Institute, pregnant people living in a state that banned abortion after Dobbs were up to three times more likely to die during pregnancy, childbirth, or soon after giving birth compared to pregnant people in states that did not ban abortion.

Methodology

The findings of this report are based on a “simulated patient” research methodology, in which research assistants posed as prospective patients and called hospitals that provide prenatal and peripartum care across the state of Oklahoma to ask questions related to emergency pregnancy care.[46] The value of this methodology is its ability to elicit realistic responses from staff, akin to how they would behave when dealing with an actual patient, thus avoiding the social desirability biases associated with self-reporting.[47] These methods have been used successfully in multiple studies of hospital practices and have been deemed scientifically and ethically sound.[48] This study was reviewed and deemed exempt from U.S. requirements for human subjects research by Physicians for Human Rights’ (PHR’s) Ethics Review Board (ERB).[49]

Two PHR research interns and one staff member were trained and used a standard script to call all hospitals in the state listed as offering labor and delivery services. Presenting themselves as prospective maternity patients choosing which hospital to go to for prenatal and peripartum care, they requested information about each hospital’s policies and procedures that would guide decision-making in: 1) cases of medical emergencies, where their life could be at risk if a pregnancy with a viable fetus were not terminated; and 2) cases of miscarriage that require procedures both when there is and when there is not fetal cardiac activity.

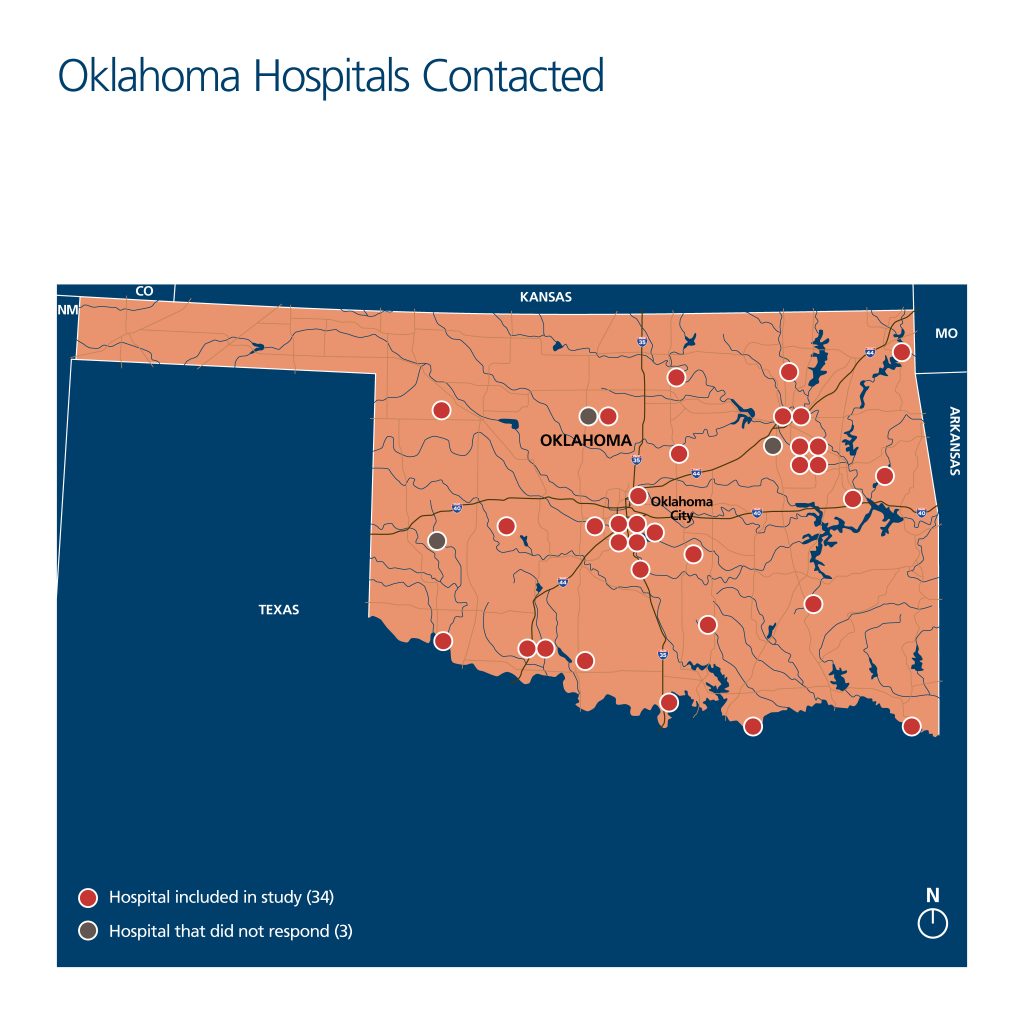

To identify hospitals to be called, the research team reviewed several databases of all registered hospitals in Oklahoma maintained by the Oklahoma Hospital Association and by OfficialUSA.com.[50] The team then examined each hospital’s website to identify facilities that offer prenatal and peripartum services. In obstetric emergencies, hospitals’ obstetrics and labor and delivery clinical teams and departments are typically where difficult decisions about what constitutes “medically necessary” abortions are made and where such procedures are eventually carried out. From the review of each hospital’s website, the research team identified 41 facilities providing labor and delivery services in Oklahoma.

Since a prospective patient would likely first seek information from hospital websites, staff reviewed each hospital’s website in October 2022 for information on care in cases of potential miscarriage and medical emergencies during pregnancy. Two hospital websites described surgical procedures to remove ectopic pregnancies. No hospital website discussed care provided in other cases of medical emergency that could threaten the pregnant person’s life, and no hospital website described possible procedures or other treatment in cases of a potential miscarriage.

Staff members then built profiles for each of the 41 identified hospitals, categorizing them according to their religious affiliation, academic affiliation, size, association with an Indigenous nation, and geography. The four identified hospitals affiliated with an Indigenous nation were not included in the calls because it is currently unclear what the legal effects of Oklahoma’s bans are within these facilities, given that the Indian Health Service, which operates them, is under federal rather than state oversight (these facilities are also affected by the Hyde Amendment).[51] Thus, a total of 37 hospitals were called during the months of November and December 2022.

The simulated patients were assigned specific regions of the state to call (east, north, central, south, west), with a greater distribution of hospitals in Oklahoma’s central and northeastern regions. Each was trained to use a caller script and standardized note-taking sheet but was encouraged to alter the language and cadence of the questions, in the interest of appearing as realistic as possible and as individual conversations warranted. Each caller introduced herself under the following identity: a 36-year-old, highly educated, affluent, married woman with mild pre-existing conditions who had recently moved to Oklahoma.[55] The researchers stated that this was their first pregnancy and that they were currently six weeks pregnant. Callers used their real first names and a fictional last name in conversations and were provided an email address and the name of a universally accepted insurance plan (Blue Preferred PPO) to give hospital staffers if requested. If asked about their ethnicity, the research assistants were instructed to give their real backgrounds; all three callers were white women. Lastly, if callers were asked about their place of residence, all explained that they lived near the hospital called.

Written notes from the calls were kept on a standardized form. When relevant, the researchers wrote down verbatim quotes from hospital staff; however, none of the calls were recorded. Personal cell phones were used to make all calls.

During the calls, simulated patients requested to be informed about hospital policies that guided decision-making processes for “medically necessary” abortions to save the life of a pregnant patient and about the internal approval processes, if any, for conducting these procedures. The caller initially asked general questions about the hospital facility, such as if the hospital offered private delivery rooms, before shifting to more specific questions about the hospital’s guidelines in cases where an abortion might be required to save the life of the pregnant patient. As a pregnant person who recently moved to Oklahoma with her spouse, each caller’s questions were meant to convey a relatively informed patient’s concerns about how state-level abortion bans might affect the care they would receive in the case of a medical emergency, particularly given the existence of pre-existing, if routine, conditions.

In all calls, the simulated prospective patients requested to be connected to a qualified hospital representative who could answer their questions about care options during pregnancy. When hospital staffers provided vague or unclear explanations of hospital policies, callers gently probed for further clarification and, when necessary, requested to speak to another hospital employee who might have more complete information. If their efforts to speak to someone knowledgeable about hospital policies were unsuccessful during the call, the caller would thank the staff member, hang up, and call again later. Calls were considered complete if the callers were able to receive an answer about hospital policies or lack thereof from a member of the staff. If the initial call was inconclusive, the researchers would call hospitals back up to two more times before concluding the case. When a hospital provided information about its policies and guidelines for clinicians (or the lack thereof), verbally or through written communication, this was considered a “complete” call, and the call sheet was finalized. As discussed below, researchers were able to conduct “complete” calls with 34 Oklahoma hospitals.