Press release available in English and Arabic

Executive Summary

Attacking health care facilities has been a deliberate tactic in the Syrian conflict, which is now 12 years old. Even as international recognition of the systematic nature of these attacks has grown in response to widespread documentation of assaults, impunity for perpetrators continues.

All parties to the conflict have perpetrated numerous acts of violence in violation of international humanitarian law (IHL). In the face of substantial evidence, however, member states of the United Nations have taken limited action to hold those responsible to account, or to protect health workers and the provision of vital health care services.

Today, international headlines rarely feature the Syrian conflict. Yet, the war in Syria is far from over. Indeed, since the 2020 ceasefire, three aerial bombardments have been carried out on health care facilities.[1]

The long-term and cumulative impacts of the conflict have generated a health care crisis for the 4.6 million civilians in northwest Syria.[2] Almost half of this population is female. Understanding how these attacks reduce availability and access to care for women and girls, including sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, is vital to protect the human right to health, and to promote advocacy efforts in Syria and beyond.

Based on primary data collected in northwest Syria, this report shines a light on the daily experiences of health care staff who provide SRH services, and, in turn, the patients who try to access these services. Providing health care is ever more tenuous there: during the month of November 2022, almost a million medical procedures took place with supplies and equipment that entered Syria as part of the cross-border operation implemented through the use of the Bab al-Hawa crossing.[3] While the impact of the violence in Syria on health care has been widely documented, the existing literature on the impact of violence on the provision of SRH care is scant. This report contributes to a greater understanding of this underexamined crisis.

The impact of violence across northwest Syria, combined with reduced donor funding and economic collapse, has meant inadequate and uneven provision of health care for Syrians, particularly women and girls. In response to the violence, providers have been forced to leave or relocate beyond the line of fighting, leaving many unable to reach the care they need. This not only impacts civilian access to services, but also increases demand on the service providers in safer areas, undermining the quality of care. The devastating earthquakes which struck southeast Türkiye and northwest Syria in early February 2023 further limit the already precarious access to health care detailed in this report.

“When health facilities were targeted, we saw pregnant women [only] during labor, instead of four or six times throughout their pregnancy. Some presented with ill-managed anemia. When we asked them why they didn’t come for medical care earlier, they said, ‘Who would dare visit the hospital when it’s being targeted? We would be crazy to stay in the hospital.’”

Female health care provider, Idlib

In order to assess the impact of violence on SRH, researchers spoke with more than 260 mostly female respondents, who shared their experience accessing or providing SRH services. Qualitative interviews with reproductive health care workers and extensive focus group discussions with displaced and resident women in Idlib and Aleppo demonstrate that continued violence poses increasing and complex barriers to health care. Syrian women in the northwest reported that fear or experience of bombings, kidnapping, or exploitation all undermine their ability to access health clinics, leaving them without care or reliant on informal health service provision. Attacks on health care facilities are frequent enough that a high number of pregnant women in northwest Syria prefer to undergo a cesarean section instead of a vaginal birth, partly to reduce the time spent inside a health care facility. They also avoid prenatal care visits.

Pregnant women reported they must travel long distances to seek medical care, putting themselves at risk. Providers and patients described deaths because of delays in care provision. Not all consequences were as visible: women also explained how the lack of access to SRH services negatively impacts both their mental health and that of their families.

As economic crisis, inflation, and the impact of the earthquakes continue to grip Syria, the cost of medicine, transportation, and private health care undermines people’s ability to access the often lifesaving care they require. Stigma, cultural expectations, and lack of awareness of their rights and of service availability make access even more difficult. The services that are the most stigmatized, including for sexually transmitted infections and HIV/AIDS care, are also the least accessible, according to those interviewed.

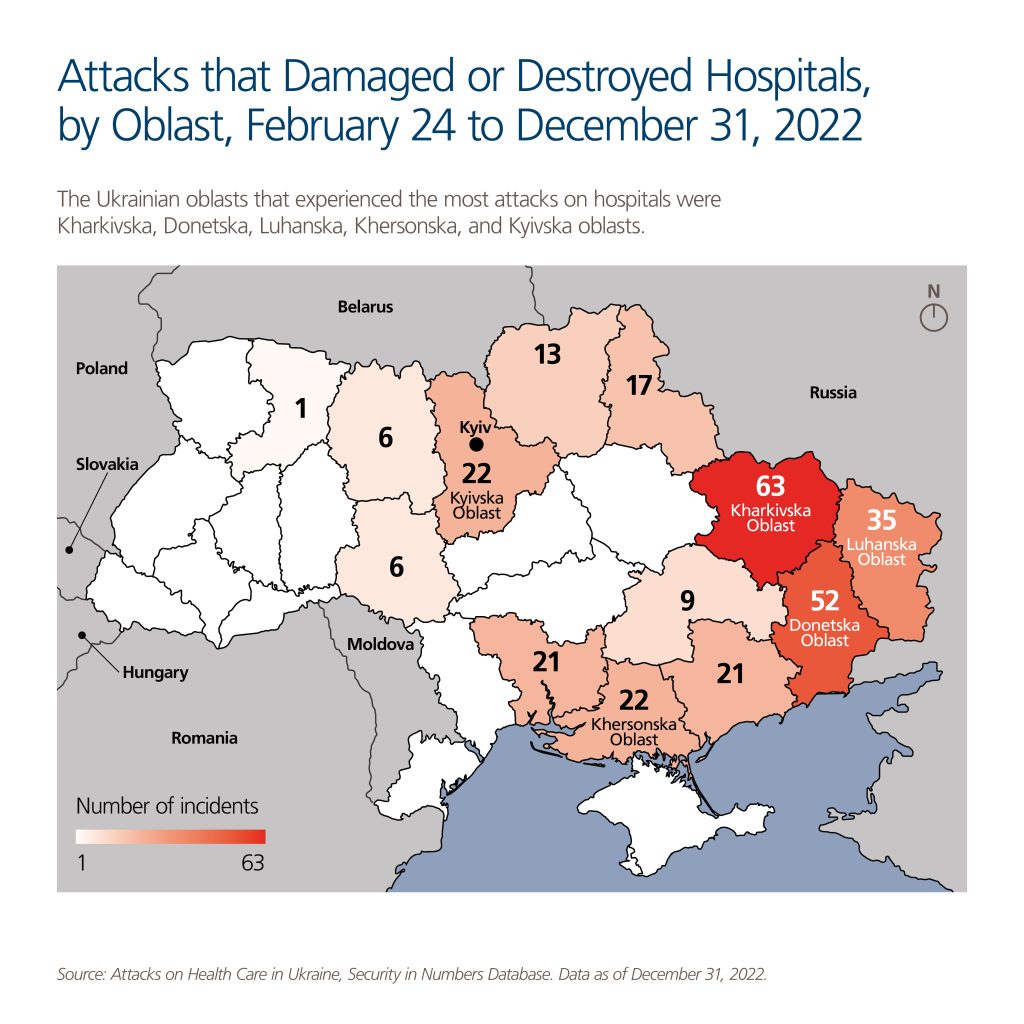

Many of the trends identified in this report can also be mapped to wider challenges that communities experiencing conflict face in meeting their health needs. Civilians and communities currently facing similar systematic violence against health care, such as in Myanmar, Ukraine, and Yemen, likely face similar barriers.

The findings of this research are intended to raise awareness of the ongoing plight of Syrians and to contribute to policy change. While health actors, including humanitarian organizations, have worked to fill the gaps in health care provision, the current approach to the crisis in Syria is inadequate. Urgent changes are needed to protect the right to health for populations in northwest Syria and ensure access for those who require medical care.

The devastating earthquakes that hit Syria and Türkiye on February 6, 2023 and the continuing damage caused by aftershocks further compound the already precarious access to health care detailed in this report. Challenges related to displacement, destruction of roads, lack of fuel, and limited health services provision will likely impact 148,000 pregnant women, 37,000 of whom are due to give birth in the three months following the earthquakes, with 5,550 women who may experience complications requiring emergency obstetric care, including C-section, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA).[4]

This report reflects the SRH concerns of those living and working in northwest Syria. It establishes a record upon which policymakers, donors, and health actors, including humanitarian organizations, may rely in addressing the crisis of SRH in northwest Syria. It provides core recommendations for the United Nations Security Council, United Nations member states, donors, health actors, and the coordination architecture.[5] Respondents emphasized that accountability, improved access to health care, greater awareness, and sufficient resources should be prioritized by policymakers and practitioners.

Introduction

Attacks on health care facilities in northwest Syria (NWS) during the conflict have reduced both the facilities and the health care workers serving the country’s largest internally displaced population. More than two-thirds of the population in NWS is displaced, and the more than 1,400 camps for internally displaced people (IDPs) are a visible reminder of the human cost of 12 years of intense conflict. Civilians in NWS are routinely subjected to shelling, airstrikes, and clashes, and 90 percent of the population lives below the poverty line.[6]

The impact of violence on health is clear. In rural Idlib, a displaced woman explained that “When they continue for a long time, bombing and bad security conditions cause many health problems. People who live in remote places, such as in tents in the mountains, on the outskirts, or in the countryside are unable to secure their basic needs.” [7]

The devastating earthquakes that hit Syria and Türkiye on February 6, 2023 have gravely worsened the humanitarian crisis in northwest Syria. In opposition-controlled areas, more than three million people were affected by the earthquakes, which, as of February 28, 2023, have caused more than 4,500 deaths and 8,700 injuries, mostly concentrated in Afrin, Harim, and Jisr-Ash-Shugur districts.[8] This has increased the need for health services, putting more pressure on medical staff, medical facilities, and health resources at a time when the entire region has been struggling with limited humanitarian access. Before the earthquakes, 30 people a day crossed the border into Türkiye to seek medical care for health issues that are unmanageable in northwest Syria, such as cancer treatment and intensive care for preterm babies. The earthquakes have made this movement largely impossible. A rapid protection assessment conducted by the protection cluster in the affected areas confirms what we know from other crises: women and girls are being disproportionally affected by the surge in needs and safety concerns in the aftermath of the earthquake, which compounds their inability to access SRH services – services that are already limited due to the impact of violence.[9]

2.3 million women and girls in NWS do not have easy access to necessary medical care, including sexual and reproductive health.

Health care in NWS depends almost entirely on cross-border provision of aid through the Bab al-Hawa border crossing with Türkiye. The current mandate for cross-border aid will expire in July 2023, unless the United Nations Security Council chooses to reauthorize it – which makes access to health care even more precarious.[10] In response to the earthquakes, two additional border crossings – Bab al-Salam and al-Raee – were opened for a period of three months.

Against this backdrop, a less visible, but no less severe, crisis of sexual and reproductive health and rights is occurring. Among other basic human rights, sexual and reproductive health (SRH) is fundamental to the right to health.[11] All parties to the conflict are obligated to uphold the right to health, including sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), and to adhere to international humanitarian law, which also protects these rights. Conflict-affected women have additional, specific sexual and reproductive health needs.[12]

This report documents the impact on women and girls of targeted violence on the availability of and access to SRH care, including basic and specialized services.[13] The report findings include:

- SRH services are insufficient due to limited staff, facilities, equipment, supplies, and medication across NWS.

- SRH care provision is limited, among other things, by the fact that many health care facilities have been built in, or relocated to, geographic areas far from the front lines, limiting access to SRH services for communities close to conflict zones. Because of the large population and demand in safer areas, these facilities experience significant overcrowding.

- In areas where SRH services are largely unavailable, respondents reported harmful coping practices, including postponing essential SRH visits and forgoing medication.

- When required SRH services are not available or practically inaccessible, there are far-reaching, negative consequences for women’s health, including for both their psychosocial well-being and that of their children.

- The most marginalized people, including women residing in camps, those with a disability, those with limited income, and those married at a young age, are most adversely impacted by the paucity of SRH care.

Because of the current status of the conflict, health care services in NWS are largely provided by humanitarian organizations. The crisis of SRH in NWS is further impacted by funding gaps, shifts in donor priorities to other crises, the deteriorating economic situation in Syria , and the toll of the devastating earthquake which struck southeast Türkiye and northwest Syria in early February 2023. In June 2021, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs reported a 60 percent funding gap in NWS and a 96.4 percent gap in health sector funding.[14] In 2022, the funding gap for the health sector in NWS increased from 46 percent in June[15] to 71.6 percent in October.[16] In addition to economic factors, social and cultural norms often impact SRH behaviors. In NWS, respondents reported practices that have had multiple negative effects on women’s sexual and reproductive rights and health, including the need to be accompanied by a male family member or an older female family member in order to access care, and the need for this family member to consent to treatment.[17]

This report reflects the SRH concerns of those living and working in NWS. It establishes a record upon which policymakers, donors, and health actors, including humanitarian organizations, may rely in addressing the underexamined crisis of sexual and reproductive health and rights in NWS.

Terms and Definitions

This report employs a number of terms, concepts, and phrases, listed below in alphabetical order.

Abortion: The original research on which this report is based was conducted in Syrian colloquial Arabic. Respondents (interviewed individually or in focus group discussions) used some sexual and reproductive health (SRH) terms in non-medical ways, reflecting their beliefs and practices. For example, many respondents referred to any pregnancy loss in Arabic, whether intentional or unintentional, as an “abortion.” Abortions can be spontaneous, induced, missed, complete, or incomplete. They can be safe or unsafe, depending on who performs them and where they are performed. For clarity, this report uses the terms “spontaneous abortion” or “induced abortion.” Spontaneous abortion is the loss of a fetus in early pregnancy, without interference. Respondents referred to “miscarriage” or a “natural abortion” to indicate spontaneous abortion. The report employs “induced abortion” for an intentional attempt to terminate a pregnancy. Induced abortion is restricted by the Syrian Penal Code and is limited to situations in which a medical specialist orders the procedure to prevent the mother’s death.[18]

Awareness: Many focus group respondents indicated the need for increased SRH awareness programming. In this context, the term “awareness” includes knowledge on the availability and functioning of SRH services as well as an understanding of the relevance of such services to their lives.[19]

Front line: This report uses the noun “front line” and the adjective “frontline” to describe areas where civilian infrastructure is targeted in violation of the 2020 ceasefire agreement. It uses “non-frontline” for areas that have experienced less violence and are closer to the Syrian-Turkish border.

Post-abortion care: A lifesaving, legal intervention, “post-abortion care” refers to therapeutic medical treatment after a pregnancy has been terminated or a spontaneous abortion has occurred. This type of care includes the treatment of any complications, if needed, information sharing, and post-abortion contraception.

Public hospital: In NWS, a hospital that does not take fees and is supported by humanitarian funding.

Sexual and reproductive health care: This report adopts the World Health Organization’s (WHO) SRH service categories, which include maternal and newborn care, contraception and family planning, clinical and psychosocial services for survivors of gender-based violence, HIV prevention and treatment, eliminating unsafe abortion, combatting sexually transmitted infections, and promoting sexual health. While not all of these categories of SRH service are currently available in Syria, they are all key to achieving SRH rights.

SRH care is provided through the “constellation of methods, techniques, and services that contribute to reproductive health and well-being by preventing and solving reproductive health problems,” including sexual health, for women and other vulnerable groups.[20]

Violence against health care: This report adopts the WHO’s definition of violence against health care as any act of physical or verbal violence, threat of violence, or other psychological violence or obstruction that interferes with the availability, access to, and delivery of curative and/or preventive health services.[21]

Methodology

This report examines the impact of attacks on health care on sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services in northwest Syria (NWS) from 2017 to 2022.This five-year time interval covers multiple events which the research team believes are likely to have impacted SRH service availability and accessibility in NWS. Major events include: the forced displacement of the population of eastern Aleppo city in 2017 following a major military offensive in late 2016; the military offensive that targeted Idlib between October 2019 and April 2020, which resulted in the biggest internally displaced person (IDP) crisis of the Syrian conflict; the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; and a cholera outbreak in 2022.

Importantly, the research team collected and analyzed the data prior to the devastating earthquakes that hit Syria and Türkiye on February 6, 2023. Therefore, these findings do not reflect the health care situation in northwest Syria after the disaster, which has only been exacerbated due to increased injuries, lack of capacity to address emergency and chronic health care needs, mass displacement, further damage to the health infrastructure and to transport, and the population´s ongoing inability to cover health-related expenses.

Using qualitative data collection and analysis, this research focuses on the availability of and access to SRH services in parts of Idlib and Aleppo governorates not controlled by the government of Syria or the Syrian Democratic Forces.[22] Researchers focused on differences in SRH availability and access in urban, rural, and camp settings, as well as frontline versus non-frontline areas.

Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), the International Rescue Committee (IRC), Syria Relief and Development (SRD), and the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) jointly conducted this original research between September and November 2022 with Shafak supporting primary data collection. The Independent Doctors Association (IDA), Relief Experts Association (UDER), Syrian Expatriate Medical Association (SEMA), and Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations (UOSSM) all contributed data to the study.

IRC and Shafak carried out 36 individual community-based interviews (CBIs) and led 26 focus group discussions (FGDs) comprising a total of 240 women in sub-districts throughout Idlib and Aleppo governorates in NWS.[23] All interviews were conducted in Syrian Arabic by data collectors trained by the organizations and recorded at the discretion of the respondent.[24] This information was supplemented by key informant interviews (KIIs) led by PHR with health experts based both inside and outside of NWS. The KIIs with health care experts, including providers and health sector planners, provided an overview of the status of SRH services in NWS.

The CBIs were conducted with an equal number of male and female professional staff with SRH expertise, including physicians, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, nutrition workers, community health workers, and health administrators. The sample included urban and rural areas (including IDP camp settings) across NWS. Approximately a third of the sample represents frontline areas (Ariha and al-Atareb sub-districts), with a female population of almost 150,000.[25] A total of 26 FGDs of no more than 10 people each were conducted with 240 total respondents between the ages of 18 and 50, including displaced and resident women. The FGDs included a mix of pregnant, breastfeeding, and married women, some with children, as well as service providers working at the sub-district level. All respondents provided verbal or written informed consent. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the IRC Institutional Review Board (IRB) and PHR’s Ethics Review Board (ERB).

Limitations

Historically, little to no data on SRH care in NWS has been gathered or reported. As a result, it is not possible to compare pre-conflict statistics related to SRH, such as maternal and newborn mortality rates, contraceptive access, the average number of antenatal visits, and other SRH services, with those provided during the conflict. Similarly, very little data has been systematically collected on the barriers to accessing SRH care.

Collecting data in conflict settings is challenging, and SRH is a particularly sensitive and stigmatized topic. Strongly held individual and societal beliefs about gender, sexuality, culture, traditions, and health care may have impacted participant willingness to speak openly about SRH issues, especially when the discussions were recorded. To mitigate these challenges, data collectors attempted to interview both males and females and include a variety of perspectives, particularly from female beneficiaries of SRH services in NWS. Female data collectors interviewed female participants in 16 of the 18 CBIs conducted with female respondents, and in all 26 FGDs.

Background: Factors Impacting Health Care in NWS

More than a decade of conflict in Syria has degraded the health care system in northwest Syria (NWS) in complicated ways. Attacks have caused humanitarian NGO-funded hospitals and clinics to relocate to safer areas, and sustained fighting has shifted the population within NWS, which includes the territories of Idlib governorate and northern Aleppo governorate, bordering Türkiye.

“The ongoing war made it necessary for donors, NGOs, and medical staff to operate in safer areas. [These areas have] a high population density, and are away from front lines, continuous hostilities, and bombardment. The international border regions are less likely to be targeted.”

Health facilities, staff, and patients have been subjected to high levels of targeted violence in NWS. Since 2017, Physicians for Human Rights has documented 144 attacks on health care facilities throughout Syria. From 2017 to 2021, the Syrian American Medical Society reported damage from explosions to 368 health care facilities.[26] Attacks have resulted not only in extensive damage to health infrastructure but have also led to high levels of casualties, displacement, and overall attrition among specialized health staff.[27] In combination with the loss of medical equipment and medicine, this has further aggravated a severe health crisis among NWS’s population.

Ongoing significant violence in NWS has not only lowered the number of functioning facilities, it has also increased the internally displaced population. Of the 4.6 million people in NWS,[28] 63 percent (2.9 million) are internally displaced persons (IDPs), of whom almost 80 percent are women and children.[29] IDP access to health facilities is particularly challenging: although 40 percent of the population in NWS live in camps, only 18 percent of all health facilities are in camp settings.[30]

“If my patient wants to go to the nearest hospital, it will cost her 50 Turkish lira ($2.65) [paying for rides in] passing cars and around 200 Turkish lira [$10.60] in a private vehicle.”

Finally, widespread poverty in NWS, exacerbated by years of conflict, has impacted the population’s access to health care because many are unable to afford the cost of transportation to health facilities. NWS is home to more than a quarter of the Syrians in need of humanitarian assistance (4.1 million out of 15.3 million nationwide).[31]Economic deterioration has had the greatest impact on IDPs, vulnerable residents, including the disabled, and the more than 16,000 Syrians who have returned to their areas in NWS after being displaced.[32]An example of the severe economic pressure on civilians is the price of food, which has increased by 85 percent compared to food prices in August 2021.[33]

The NWS Health System: Beyond the Numbers

Health care facilities in NWS provide sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care but have struggled to meet the significant and growing needs of the population. Although SRH care is provided in private and public facilities, the majority of the population can only afford public facilities. The high demand on the free (or public) system results in patient overcrowding. Although NWS technically meets the minimum World Health Organization requirement for health facilities per population, in reality, these facilities are concentrated in areas considered safer from attack. This uneven geographic distribution of health facilities creates an access barrier, especially for some of the most vulnerable.

“[There is] fear of bombing, kidnapping, or harassment. Not all health centers are close to my residence, so I must rent a car to get to the hospital, and then I may be subjected to financial exploitation by the driver…. As a woman, I avoid going to [medical] centers alone.”

A health care expert involved in planning health programs confirmed that donors and non-governmental organizations have been forced to operate in the area closer to the international border with Türkiye, explaining, “The ongoing war made it necessary for donors, NGOs, and medical staff to operate in safer areas. [These areas have] a high population density, and are away from front lines, continuous hostilities, and bombardment. The international border regions are less likely to be targeted.”[34] This northern region has seen a huge population increase, and health workers there reported significant overcrowding of medical facilities, and a lack of specialized health care workers, such as those who provide SRH care.[35]

Families experiencing extreme poverty may be forced to live in areas close to the front line, where housing is less expensive. Women in frontline areas such as Ariha and Jisr as-Shughur reported that long distances and unsafe roads pose a practical barrier to accessing medical care. Transportation costs are prohibitively expensive for people living close to the front line, as well as those in rural and isolated areas. A health care provider in urban Idlib explained that, with a median estimated daily wage for unskilled labor of around one U.S. dollar, patients cannot always afford transportation to access health care. “If my patient wants to go to the nearest hospital, it will cost her 50 Turkish lira ($2.65) [paying for rides in] passing cars and around 200 Turkish lira [$10.60] in a private vehicle.”

A displaced woman in urban Aleppo explained the impact of violence on her health choices, noting that getting care is difficult: “[There is] fear of bombing, kidnapping, or harassment. Not all health centers are close to my residence, so I must rent a car to get to the hospital, and then I may be subjected to financial exploitation by the driver…. As a woman, I avoid going to [medical] centers alone.”[36]

NWS SRH Services Landscape

The humanitarian sector in NWS represented by local and international non-governmental organizations has stepped in to bridge the gap in health services following the withdrawal of the Syrian government from territories that were captured by opposition forces beginning in 2012. Humanitarian agencies have offered services that evolved over time based on the needs, priorities, and available resources.[37] Individual SRH services differ in terms of availability and geographic distribution within and between regions across the northwest, and in some places are simply unavailable.

Humanitarian health care workers in Syria adopted the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP), a set of guidelines for SRH service delivery in crisis settings.[38] The MISP aims to facilitate the coordination of SRH services, prevent and manage the consequences of sexual violence, reduce HIV transmission, minimize maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, and plan for comprehensive SRH services in the post-crisis phase.[39]

Findings

The research yielded several key findings, all of which merit further study. A variety of themes emerged from the significant portion of the data that involved the impact of violence on maternal and newborn care, including availability, supply relative to the population’s need, and the role of violence in shaping birth preferences. Other topics, such as family planning, gender-based violence (GBV) – including early marriage – abortions and post-abortion care, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and the impact on mental health of poor access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care were mentioned in less detail but provide a window into the health care struggles of women in northwest Syria (NWS).

The Impact of Violence on Maternal and Newborn Child Health

Violence has limited the availability of certain services in frontline areas, and driven population shifts that result in high demand on existing facilities. The World Health Organization (WHO) initiative “Health Resources and Services Availability Monitoring System” reported 367 functioning medical facilities in NWS in September 2022.[40] A separate monitoring initiative led by the United Nations Population Fund, and run by the SRH Technical Working Group (health cluster) and the GBV Sub-cluster (protection cluster), reported in 2022 that only seven percent (50) of these facilities offer the packages of maternity care known as either comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care, or basic emergency obstetric and newborn care services.[41] The same assessment found that outpatient reproductive health services are offered in fewer than 40 percent (142) of the facilities. Nevertheless, the SRH Technical Working Group estimates that between January 2021 and September 2022, SRH service providers offered more than 3.9 million reproductive health consultations and performed 220,000 deliveries.[42]

Availability and Need

The SRH Technical Working Group partners provide essential SRH care through the Minimum Initial Service Package at three levels of health care facilities: two levels of primary health centers (PHCs), including facilities that offer basic emergency obstetric care and those that offer comprehensive emergency obstetric care. PHCs include mobile clinics and health points. PHCs distribute male condoms and provide clean delivery kits,[43] treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and oral and injectable contraception. In addition, there are 14 health facilities in NWS providing basic emergency obstetric and neonatal newborn care, which can provide emergency medical care to women experiencing pregnancy or childbirth complications.[44] The 36 highest-level facilities in NWS have comprehensive emergency obstetric and neonatal care, with the capacity to perform cesarean section deliveries, provide blood transfusions, and administer post-rape treatment.[45]

Health care workers confirmed that public facilities provide free delivery care for pregnant women, including after childbirth, in addition to newborn care.[46] However, the large population utilizing public hospitals in areas farther from the front line results in overcrowding, which has caused significant gaps in maternal and newborn services.[47] Rural and frontline areas, on the other hand, have less availability of maternal and newborn care than in urban facilities. A doctor in rural Aleppo explained that although the health centers near his village are supposed to provide obstetric care, they are not equipped to do so.[48]

Areas on the front line, such as Ariha sub-district, illustrate the mismatch between the available resources and the need. Between July and September 2022, only six facilities in Ariha provided family planning counseling and family planning kits to a population of more than 180,000. In contrast, 209 facilities in non-frontline areas of the NWS provided family planning kits and counseling to 4.4 million people. This translates to 4.8 facilities per 100,000 population in non-frontline areas compared with 3.3 facilities per 100,000 in Ariha, a 31 percent greater workload on such frontline area facilities. Unable to cover the population’s needs, these facilities are easily overwhelmed, which forces patients to travel to non-frontline areas, further burdening the system in these localities.

The number of skilled providers operating within facilities also greatly impacts access to SRH care. For example, only two facilities in Ariha provide skilled care to assist with childbirth,[49] while the service is available in 48 facilities in safer areas. A health center director in urban Ariha noted,

“After the last bombing campaign, almost all the [health care-providing] organizations withdrew their projects; the health centers and hospitals did not remain. Some have returned recently, but they are insufficient and do not meet the need.”[50]

The violence has also impacted the number of SRH care providers in Ariha: since 2017, the number of midwives there decreased from 33 to 19 (42 percent decrease), and the number of gynecologists decreased from 9 to only 4 (56 percent decrease). [51]

Attacks Impact Childbirth in NWS

Health facilities, staff, and patients have been subjected to high levels of targeted violence in NWS. Since 2017, Physicians for Human Rights has documented that 55 percent of attacks occurred in NWS, targeting 60 facilities.[52] Almost 90 percent of the attacks were conducted by aircraft or land-to-land missiles.[53] Three attacks were perpetrated in 2021 and targeted facilities in NWS, of which two provide SRH services. The attack on al-Atareb hospital on March 21, 2021 resulted in a 78 percent reduction in the number of reproductive and neonatal care consultations in the facility.[54] The attack on the al-Shifa Hospital on June 12, 2021 destroyed the labor and delivery unit and killed 13 people, four of whom were hospital and ambulance staff.[55]

“After the last bombing campaign, almost all the [health care-providing] organizations withdrew their projects; the health centers and hospitals did not remain. Some have returned recently, but they are insufficient and do not meet the need.”

Health center director in urban Ariha

Health workers reported how violent attacks on health care have impacted maternal and newborn care. During shelling, mothers may give birth while traveling on roads in areas of active fighting.[56] A female health care administrator in a rural internally displaced persons (IDP) camp explained that after the al-Shifa Hospital health center was bombed, people were forced to travel far away to Afrin Hospital and “many women gave birth in the car on the way because of the distance.”[57] Displaced women in focus groups recounted how pregnant women were forced to give birth at home or on the road during heavy shelling, and that women who miscarried couldn’t access the health center for care.[58]

One displaced woman shared the tragic consequences of violence on her family:

“My relative gave birth at night, and the child needed an incubator. Because of the shelling of the village of al-Atareb, she could not reach the hospital, and the child suffered from hypoxia and was transferred to Türkiye, where he died.”[59]

Violence Increases the Preference for Cesarean Sections

Violence has changed childbirth practices in NWS. Seeking to minimize their time in health facilities due to the risks of attacks, more women have opted for cesarean sections over natural births. In 2000, the cesarean rate was 14.8 percent.[60] A study from 2004 showed that the facility-based cesarean section rates were 12.7 per cent in government hospitals.[61] After the beginning of the Syrian conflict in 2011, the rate increased. A study published in 2021 showed a peak in caesarean sections to 33.2 percent in March 2020 after the military campaign on NWS, following a drop in SRH service provision that correlated with the attacks.[62] The SRH working group, using data from a total of 356 SRH-providing facilities between January 2021 and September 2022, found that the average cesarean section rate remained significantly higher than pre-conflict rates at 23 percent.[63]

A health care provider who worked in directly targeted health facilities explained that vaginal delivery can require many hours, whereas a cesarean section takes only a few minutes and requires only six to seven hours for recovery. He explained that while not ideal, cesareans provide an element of certainty in a context in which patients feel “as if they were going to a front line when visiting a hospital, given how frequent attacks on health care were.” He added that he and his colleagues would avoid keeping the mother overnight if the recovery rooms were not underground, to avoid exposing her to bombings. While scheduling cesareans protected the staff and patients from facility attacks during unpredictably lengthy vaginal births, the health care provider observed that this approach often “negatively impacted the physical and psychological patient outcomes,” since the longer recovery period required post-cesarean may increase post-partum infection rates and increase pain.[64]

While scheduling a cesarean has come to be considered safer, during a direct attack on a hospital, nobody is protected. A woman described giving birth during a bombing:

“I was in the operating room. I could hear the sound of planes flying over the hospital, and I was very stressed and crying. I was not fully anesthetized. The doctor had to give me general anesthesia after he had originally started epidural anesthesia so that he could complete the surgery. I was giving birth and heard the planes over the hospital. I was afraid for my family and husband who were in the hospital. As soon as I left the operating room, before I even woke up, they took me home, without examining me or my child. This created a bad psychological condition for me, with constant crying, which led to my loss of milk.”[65]

The Impact of Violence on Other Specialized SRH Services

The impact of violence on access to maternal and newborn health was one of the most documented within this study. However, the provision and ability to access all types of SRH services have been affected by 12 years of conflict. The analysis below discusses some of the main barriers women face when accessing specialized SRH services such as family planning, GBV services, post-abortion care, and STI services – including HIV/AIDS support – and the impact this lack of SRH care has had on women’s mental health. Ultimately, it highlights the role of violence against health care in aggravating the lack of SRH services and the ability to utilize them.

Family Planning

Focus group respondents indicated that family planning was among the most straightforward services to access. However, health care workers and administrators expressed concern that their patient population lacked sufficient awareness about family planning services, noting cultural and social norms that value fertility and having many children might form a barrier to women availing themselves of such services.

Contraceptive kits and services are available free of charge in NWS’s public facilities, but respondents reported that these cannot meet the high level of need evidenced by patient overcrowding.[66]The lack of accessible public health facilities for IDPs can force them to forgo family planning or to purchase contraception through the private system. Women in al-Jama’a IDP camp in Idlib requested more family planning clinics.[67] Because transportation is costly and dangerous during attacks, a health manager in rural Idlib described the “need to provide mobile teams and awareness sessions on family planning, which positively affects the community.”[68]

Gender-based Violence (GBV)

While GBV is a sensitive topic, both health care workers and women indicated that it must be addressed. In a focus group discussion in an informally organized IDP camp in Aleppo, al-Zeitoun, women reported the need for “increasing awareness regarding family planning and GBV … especially in camp settings and among IDPs.” They added that the camp needed to prevent GBV, since women “may be exposed to marital beatings that prevent them from reaching care.”[69] In urban Idlib, a nurse explained the need to “intensify sessions to raise awareness of GBV and introduce GBV services,”[70] and a health manager suggested provision of in-home awareness sessions to individuals or groups of women.[71]

Early marriage is a form of GBV of concern throughout NWS. In fact, high rates of suicide among adolescent girls in NWS have been linked to early marriage.[72] A nurse in rural Aleppo noted the need for early marriage awareness campaigns for all segments of society, observing, “It may lead to violence, and the girl may be forced to do anything. If she gets married at a young age, and cannot live with her husband, she may be afraid to return to her family. She may do something to herself.”[73]

Access to Post-Abortion Care

Displaced women were concerned about the dangers of not receiving post-abortion care (PAC). Post-abortion risks include bleeding, severe infections, and complications that may lead to death or the inability to conceive again.[74] Unfortunately, PAC availability is uneven, and there are an insufficient number of PAC-providing health care centers in rural and frontline areas of NWS for the population.[75] Access for patients in rural and remote areas is limited by inconsistent and expensive transportation options. In practice, respondents said, husbands or heads-of-household needed to consent in order for women to seek PAC, as well as provide the transportation support to reach PAC services.[76]

In urban Aleppo, a respondent in a focus group described her ever-present fear of attacks when accessing post-abortion care. Describing her spontaneous abortion, she said, “There were planes in the sky of the village [aerial attacks], and my husband was not present, and I needed transportation. I was afraid to go by car with strangers alone. I experienced heavy bleeding, severe anemia, and I passed out.”[77]

Sexually Transmitted Infections and HIV/AIDs

Respondents among both patients and health care workers reported deep stigma based on social and cultural norms around accessing health care for STIs and HIV/AIDS. Provider consultations and treatment for STIs in NWS are available in facilities offering other health services, in order to avoid stigma and protect patient privacy. Nonetheless, more programming is needed.[78] A nurse in urban Idlib reported the need for “programs addressing the urgent human right to HIV care specific to women, children, and vulnerable groups in the context of prevention, care, and access to treatment.[79]

Across NWS, more STI education was requested. In urban Idlib, both male and female health care workers described the need for broad community education.[80] In rural Aleppo, a health director noted that women and girls must understand the health impacts of STIs;[81] this was echoed by a nurse who stated they must understand “the need to treat [STIs] as soon as possible so they do not worsen.”[82]

A nutrition worker shared her impression that, with regard to people seeking STI treatment, “Society does not understand, and takes an inferior, negative, and stigmatized view.”[83] Some health professional respondents appeared reluctant to acknowledge that STIs and HIV/AIDS exist in NWS, reflecting potential widespread bias among providers.[84]

Lack of Access to SRH Services Impacts Mental Health

Focus group discussions with displaced and resident women demonstrated how the lack of access to SRH care and ongoing violence result in mental health issues in NWS. A female midwife in urban Idlib expressed her concern that support for postpartum depression must be made available.[85] In rural Idlib, a focus group participant suggested there should be “mobile teams to provide access to those who cannot leave the house.”[86] Women in focus groups prioritized increased access and community capacity building.

Both health care providers and community member respondents were not always aware of existing efforts and available services, indicating that more resources are needed to educate the community about the availability of mental health and psychosocial support efforts.

Legal and Policy Analysis

All parties to the conflict in northwest Syria (NWS) are obligated to protect the right to health, including the right to sexual and reproductive health (SRH), for civilian populations in areas they control.[87] Donors have an ethical obligation to support humanitarians in promoting the right to health by providing assistance without discriminatory effect. This includes the duty to provide care to the most vulnerable, including women and the disabled.

International Humanitarian Law (IHL)

Any attack that deliberately targets health care facilities, or that does not take appropriate measures to avoid the destruction of health care facilities, is illegal. IHL requires special protections for medical personnel and facilities to ensure the functioning of health care throughout a conflict.[88] It also prohibits the targeting of civilians[89] and protects the care of the wounded and the sick.[90] Finally, IHL requires all parties to a conflict to respect the protection, health, and assistance needs of women affected by armed conflict.[91] Pregnant and breastfeeding women should receive special care with regard to the provision of assistance, including food, clothing, medical assistance, evacuation, and transportation.[92]

Civilians in conflict areas have the right to receive humanitarian aid, including medical and other supplies essential to survival.[93] IHL allocates primary responsibility for meeting civilian needs to the state or party that controls the territory in which the civilians are located.[94] A non-state armed group that is organized and exercises administrative control over territory, as is the case in NWS, has the same duties as a state party to the conflict.[95] Multiple United Nations Security Council resolutions have stated that organized armed groups exercising effective control over territory and carrying out administrative and public functions are responsible for protecting the rights of civilians in the territories they control.[96]

International Human Rights Law

Although Syria is party to numerous treaties that are relevant to SRH, three treaties are of particular relevance to SRH rights.[97]

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) requires states to address the specific health needs of women, including those living in poverty, rural settings, and in situations of humanitarian emergency. CEDAW further requires parties to provide access to educational material “to ensure the health and well-being of families, including information and advice on family planning.”[98] CEDAW also requires that states take measures to eliminate discrimination against women “in the field of health care in order to ensure … access to health care services, including those related to family planning” and requires them to ensure “appropriate services in connection with pregnancy, confinement and the post-natal period, granting free services where necessary, as well as adequate nutrition during pregnancy and lactation.”[99] The Convention further provides that women have the right to decide the number and spacing of their children and “to have access to the information, education, and means to enable them to exercise these rights.”[100]

In regard to SRH, the United Nations (UN) CEDAW Committee, which monitors implementation of the Convention and provides authoritative interpretations as to state party obligations, recommends that parties

“Ensure that … health care includes access to sexual and reproductive health and rights information; psychosocial support; family planning services, including emergency contraception; maternal health services, including antenatal care, skilled delivery services, prevention of vertical transmission and emergency obstetric care; safe abortion services; post-abortion care; prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections, including post-exposure prophylaxis; and care to treat injuries such as fistula arising from sexual violence, complications of delivery, or other reproductive health complications, among others.”[101]

The CEDAW Committee notes the link between conflict and gender-based violence, since conflict exacerbates existing gender inequalities, “placing women at a heightened risk of various forms of gender-based violence by both State and non-State actors.”[102]

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)[103] provides for SRH-related rights, including the right to privacy and freedom from torture, cruel, and inhuman or degrading treatment, as well as the right to life (Article 6). The Human Rights Committee, which monitors the ICCPR, has determined that protecting the right to life includes the following obligation:

“State parties must provide safe, legal and effective access to abortion where the life and health of the pregnant woman or girl is at risk, or where carrying a pregnancy to term would cause the pregnant woman or girl substantial pain or suffering, most notably where the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest or where the pregnancy is not viable.”[104]

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) also provides for the right to health.[105] In interpreting the Covenant, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) has determined that sexual and reproductive health rights are integral to the right to health and are “indispensable to [women’s] autonomy and their right to make meaningful decisions about their lives and health.”[106]

The obligations set out in these treaties must be respected, notwithstanding the emergency conditions prevailing in NWS. The CEDAW Committee has stated that states should “adopt strategies and take measures addressed to the particular needs of women in … states of emergency.”[107]

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has clarified that this means that health facilities, goods, and services must be “accessible to everyone without discrimination.”[108] Importantly, the ICESCR has recognized that international cooperation and assistance are key for realization of the right to SRH. The Committee’s General Comment 22 explicitly states that SRH is a crucial part of the human right to health and places an obligation on states to seek international assistance in situations where it cannot provide for these rights, recognizing the role UN entities play in realizing this right.[109]

All parties to the conflict in northwest Syria are obligated to protect the right to health, including the right to SRH, for civilian populations in areas they control.[110]

Donors have an ethical obligation to support humanitarians in promoting the right to health by providing assistance without discriminatory effect. This includes the duty to provide care to the most vulnerable, including women and the disabled.

Conclusion

For 12 years, mass atrocities have devastated Syria’s population and attacks on civilian infrastructure have choked its health care system. Continued attacks on health care compound the already challenging context within which many health care providers are operating. Violence has severely impacted the availability of and access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, which should be addressed at the community, donor, and service provision levels.

In addition to the direct physical harms to SRH care providers and patients, the indirect impacts of violence on SRH services, though under-studied, are clear. These include SRH-related mental health issues and the increase of negative social practices such as early marriage, which the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women has declared a form of gender-based violence.[111] This means that women and girls disproportionately feel the effects of attacks on health care. When coupled with a shrinking space for humanitarian response and the failure to secure a long-term political solution to the conflict in Syria, the crisis of SRH is likely to worsen, disproportionately impacting women and girls.

The findings of this study amplify the voices of affected women and health care workers regarding SRH needs on the ground. They demonstrate how the damage and destruction of health facilities in northwest Syria (NWS) during the conflict have, over time, resulted in a dire shortage of health facilities and workers to meet the needs of the population. Within this context, SRH services have become increasingly insufficient, particularly affecting the most marginalized, including women in camps, those with disabilities, those with limited income sources, and adolescent girls married at a young age. Further, inflation and extreme poverty have limited the means of many women, preventing them from accessing the full range of services, even when available. The demonstrated shift of donor funding to facilities in non-frontline areas rather than frontline areas has meant that many displaced women and those living in remote areas can’t avail themselves of these services. Finally, social and cultural norms pose additional barriers for women seeking SRH services; these have produced a culture of fear and hesitation among many women and adolescent girls. Meeting their need for care requires as an urgent matter better transportation to services, more information, the tools and knowledge to support their communities, and better overall coverage of SRH services delivery.

These issues are not new, but their documentation and tracking are crucial to measuring the depth of violations of human rights in Syria in how Syrian women and girls are physically and psychologically affected. The research presented in this study is further evidence of the humanitarian community’s imperative to achieve a more coordinated and holistic approach in NWS to health, based on community needs.

As Syria enters its thirteenth year of conflict, it is vital now, more than ever, that the international community reaffirm the importance of adherence to international humanitarian law and redouble diplomatic efforts for accountability. The responsibility to change both the access to and the provision of SRH services lies not only with parties to the conflict, but also with the aid and development sector, and with the international community. There is a need to push for accountability in parallel with a serious commitment to addressing violations of international law by parties to the conflict. There should be a commitment from donors to not only increase overall humanitarian assistance, but also to increase funding for essential SRH services.

Recommendations

Considering the impact of ongoing violence on the provision of health care in northwest Syria and the effects it has had on the ongoing sexual and reproductive health crisis, compounded by the devastating February 2023 earthquakes in Syria and Türkiye, more must be done to support both health care facilities and providers.

We call on the concerned parties to take the following actions in their response to the earthquakes:

To Donors and Health Actors:

- Ensure that humanitarian aid enters northwest Syria at scale and speed through all viable routes without restrictions;

- Provide immediate and flexible funding to support emergency response efforts to the current crisis;

- Reduce current barriers to accessing SRH services, primarily the lack of transport, income, and information, specifically targeting those most marginalized;

- Ensure that lifesaving SRH services are integrated into the emergency health response;

- Ensure that members of the affected population have access to fact-based information about current SRH service availability;

- Continue systematic data collection and analysis to enable prioritization based on needs, such as to women, girls, and other vulnerable populations; and

- Build the local capacity of the health system in northwest Syria to provide SRH services that are only available in Türkiye but inaccessible due to the interruption of cross-border referral services.

To All Parties to the Conflict:

- Ensure immediate, unhindered humanitarian assistance to all communities affected by the earthquakes in northwest Syria; and

- End all attacks on civilians and other violations of international humanitarian law, and protect and respect the right of the wounded and sick to seek health care.

To Active Governing Entities in Northwest Syria:

- Ensure that humanitarian assistance is available and accessible to all affected communities in northwest Syria and is distributed based on need; and

- Ensure that the most vulnerable populations – such as women, girls, and people with disabilities – among those affected by the earthquake have access to emergency SRH services.

To the United Nations (UN) Security Council and UN Member States:

- Ensure that life-saving humanitarian aid is able to enter Syria at scale and speed through all viable routes without restrictions.

There are concrete steps that parties to the conflict, the international community, humanitarian organizations, and donors must take to support the availability of and access to sexual and reproductive health care in northwest Syria. The international aid community, including donor governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), must work to ensure more services are provided, while addressing the barriers to access noted throughout this report.

We call on the concerned parties to take the following actions:

To All Parties to the Conflict:

- Cease all attacks on health care and ensure the protection of health care workers as obligated by international humanitarian law.

To Health Actors:

- Provide additional financial and technical support for sustainable strategies to increase access to SRH services, such as support to existing health networks and the use of mobile health facilities;

- Build health work force capacity, prioritizing the work of female health care providers in order to overcome potential cultural barriers to accessing SHR services, and support to local medical schools;

- Ensure meaningful access is available to a full package of SRH services, prioritizing such interventions to marginalized groups and ensuring there is fair geographic distribution and equity in service provision within communities, both displaced and host;

- Comply with minimum standards for coordination of humanitarian health system rehabilitation to avoid inequitable access to SRH care;

- Support health facilities, health workers, and social workers in addressing misinformation and awareness-building initiatives for women, men, girls, and boys to better understand what SRH services are available and how to access them;

- Adopt a holistic approach to SRH service provision, which includes awareness-raising campaigns around SRH rights and de-stigmatization at the community level, and that focuses on both health-seeking behavior and perceived health priorities;

- Ensure that SRH service provision is integrated into wider health strategic planning;

- Integrate mental health and psychosocial support activities into SRH service provision and adopt a cross-cutting approach; and

- In hard-to-reach areas, strengthen community networks through structured psychosocial support programs.

To Active Governing Entities in Northwest Syria:

- Ensure that humanitarian health sector services are available for all populations, equitably distributed geographically, accessible, and at a level commensurate with community need;

- Promote coordination within the health governance sector by engaging with local actors, including NGOs, United Nations (UN) agencies, and donors;

- Empower community-led initiatives to increase the number of ground-up approaches to health care system development to reflect patient populations’ needs and desires; and

- Prioritize accessibility and availability of health care for the physically disabled and for women.

To Donors:

- Increase support to the health sector of the Syria Humanitarian Response Plan through increased, flexible, multi-year funding that covers population needs in both the short- and long-term;

- Sustain and increase SRH and mental health and psychosocial support funding, with a focus on sustainable service provision strategies;

- Ensure the adequate funding of SRH services, particularly emphasizing that they reach the most vulnerable populations (i.e., those closest to the front lines, displaced people, adolescents, and those with disabilities);

- Ensure resource allocation and planning is informed by evidence and guided by the voices of those most affected: women, girls, and health staff; and

- Plan specific investments in programs that repair, restore, and fortify damaged or destroyed health facilities, in addition to other civilian infrastructure impacted by such attacks.

To the United Nations Security Council and UN Member States:

- Call on all parties to the conflict to uphold their obligations under international humanitarian law and ensure the protection of health care from attack;

- Elevate humanitarian diplomacy and center Syria-focused strategies and policies around the protection and expansion of humanitarian access to ensure aid delivery is needs-based, independent, and depoliticized by all parties to the conflict;

- Reauthorize UN Security Council Resolution 2672, before the July 2023 deadline, to maintain UN-led cross-border access into northwest Syria through the Bab al-Hawa border crossing for a minimum of 12 months;

- Break the cycle of impunity by ensuring that perpetrators of attacks against health care and other violations inside Syria are held to account; and

- Work to strengthen implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 2286 to protect health facilities and personnel from attack and hold perpetrators accountable.

To the Wider Whole of Syria Humanitarian Coordination System:

- Demand protection of health care workers and facilities;

- Enforce standards for SRH service delivery, including the Minimum Initial Service Package;

- Track the rebuilding and rehabilitation of facilities that provide SRH services;

- Support comprehensive monitoring and analysis of attacks against health care and its impacts;

- Deliver SRH-related medication and supplies to northwest Syria to address inequitable distribution; and

- Monitor SRH needs and the provision of SRH services and share regular analysis to inform priorities for programming, advocacy, and funding activities.

Acknowledgments

Principal Contributors

Physicians for Human Rights (PHR)

Houssam al-Nahhas, MD, MPH, Middle East and North Africa researcher

Adrienne L. Fricke, JD, MA, PHR expert consultant

Diana Rayes, MHS, PhD student, Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

International Rescue Committee (IRC)

Ihlas Altinci, MD, Emergency Response Team health coordinator

Jennifer Higgins, MA, Syria policy, advocacy, and communications coordinator

Leonie Tax, LLM, MSc, health and protection data specialist

Syria Relief & Development (SRD)

Abdulselam Daif, MD, MSc ENT surgery, MSc, Epi., senior strategic advisor

Okba Doghim, MD, MSc student, programs director, Sexual and Reproductive Health Technical Working Group co-lead

Amany Qaddour, MHSA, regional director; DrPH candidate and associate, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; Visiting scholar, Brown University Center for Human Rights & Humanitarian Studies

Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS)

Ahmad Albik, MD, MEAL (monitoring, evaluation, accountability, and learning), and information manager

Mohamed Hamze, DDS, CES, DU, MSc, Health Research Department manager

The contributing agencies of this report would like to thank the following individuals and partners who provided guidance and support during the research project.

PHR leadership and staff contributed to the writing and editing of this report, including Erika Dailey, MPhil, director of advocacy and policy; Christian De Vos, MSc, JD, PhD, director of research and investigations; Michele Heisler, MD, MPA, medical director; Thomas McHale, SM, deputy director of the Program on Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones; Karen Naimer, JD, LLM, MA, director of programs; Catherine Pilishvili, MA, international advocacy officer; Payal Shah, JD, director of the Program on Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones; Kevin Short, deputy director, media and communications; Gerson Smoger, JD, PhD, interim executive director; and Middle East and North Africa interns Samia Daghestani and Justin Liu.

IRC leadership and staff contributed to the data collection, analysis, writing, and editing of this report, including Bushra Acam, MSc, northwest Syria (NWS) health information management officer; Mohammad AlJasem, MD, NWS health coordinator; Moder Almohamad, MSc, NWS senior protection manager; Nur Barakat, NWS senior health officer; Sanni Bundgaard, MSc, technical advisor SRH (sexual and reproductive health) & WPE (women’s protection and empowerment) integration; Haya Qdeimati, MEAL expert and researcherconsultant, Marcus Skinner, MSc, humanitarian and conflict policy lead, and all IRC northwest Syria technical teams.

SRD leadership and staff contributed to data collection, technical review, writing, editing and outreach related to this report, including Boraq Albsha, media manager; Hassan Al Qasem, MEAL coordinator; Sosan Azmeh, marketing & advocacy manager; Ahmad Odaimi, MD, MSc, SRD country director (interim), and all SRD northwest Syria technical teams.

SAMS leadership and staff contributed to the writing and editing of the report, including Evan Barrett, SAMS Head Quarter advocacy manager, and Dima Marrawi, Türkiye office advocacy manager.

The contributing agencies would like to thank Anas Barbour, MA, Shafak senior health and nutrition program manager, Mahmoud Sabsoub, Shafak health project manager, and all Shafak data collection teams; the Independent Doctors Association (IDA); the Relief Experts Association (UDER); the Syrian Expatriate Medical Association (SEMA); and the Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations (UOSSM) for their data contributions to the study. The team would also like to thank the more than 260 respondents who shared their experiences as part of this survey.

The report benefited from review by Adam Richards, MD, PhD, MPH, PHR board member and associate professor of global health and medicine at The George Washington University, Milken Institute School of Public Health and School of Medicine and Health Sciences. It was reviewed, edited, and prepared for publication by Claudia Rader, MS, PHR senior communications consultant, with assistance from Samantha Peck, PHR program and executive associate.

The contributing agencies are grateful to Ali Barazi and his associates for Arabic translation services and to Elif Kaya for the Turkish translation. The contributing agencies are especially thankful for the health care and humanitarian aid workers and health experts inside Syria and beyond who are working tirelessly to provide sexual and reproductive health services in northwest Syria.

This document covers humanitarian aid activities implemented with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Union, and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Annexes

Annex I – Methods

Annex II – Survey Tools

Annex III – Availability of Selected Reproductive Health Services in Northwest Syria

Endnotes

[1] Physicians for Human Rights, “Illegal Attacks on Health Care in Syria,” Feb. 2022, https://syriamap.phr.org/#/en.

[2] United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), “North-west Syria Situation Report,” Jan. 24, 2023, https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/syria/.

[3] UNOCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: Cross-Border Humanitarian Reach and Activities from Türkiye (November 2022),” Jan. 16, 2023, https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/syrian-arab-republic-cross-border-humanitarian-reach-and-activities-turkiye-november-2022.

[4] UNOCHA, “Flash Appeal: Syrian Arab Republic (February – May 2023,” Feb. 14, 2023, https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/flash-appeal-syrian-arab-republic-earthquake-february-may-2023.

[5] For a history of the development of the global humanitarian coordination structure, referred to as “humanitarian architecture,” see ICVA, The IASC and the global humanitarian coordination architecture: How can NGOs engage?, May 15, 2017, https://www.icvanetwork.org/uploads/2021/07/Topic_1_humanitarian_coordination.pdf; to understand how the UN cluster system works within the humanitarian coordination architecture, see UNOCHA, “Who does what?,” Jan. 14, 2019, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/coordination/clusters/who-does-what.

[6] Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor, “Syria: Unprecedented rise in poverty rate, significant shortfall in humanitarian aid funding” Oct. 17, 2022, https://euromedmonitor.org/en/article/5382/Syria:-Unprecedented-rise-in-poverty-rate,-significant-shortfall-in-humanitarian-aid-funding.

[7] FGD #22, Rural, Armanaz, Idlib.

[8] UNOCHA, “Earthquakes: North-west Syria: Flash Update No. 14 (as of 28 February 2023),” Feb. 28, 2023, https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/earthquakes-north-west-syria-flash-update-no-14-28-february-2023.

[9] Protection Sector, “Rapid Protection Assessment Findings: Syria Earthquake, February 2023 Protection Sector Report,” Feb. 21, 2023, https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/rapid-protection-assessment-findings-syria-earthquake-february-2023-protection-sector-report.

[10] Physicians for Human Rights, ““A Nightmare Every Six Months”: UN Security Council Extension of Cross-Border Aid Keeps Millions of Syrians in Dangerous Limbo,” Jan. 10, 2023, https://phr.org/news/a-nightmare-every-six-months-un-security-council-extension-of-cross-border-aid-keeps-millions-of-syrians-in-dangerous-limbo/.

[11] SRH is related to multiple human rights the government of Syria is obligated to uphold, including the rights to life, health, non-discrimination and equality, privacy, freedom from torture and ill treatment, benefits of scientific progress, and determination of the number and spacing of one’s children. See the “Legal and Policy Analysis” section of this report for more information.

[12] Women and girls in conflict settings have increased SRH needs resulting from their increased vulnerability, including a higher risk of infectious diseases and experiencing gender-based violence. Mariella Munyuzangabo et al., “Delivery of sexual and reproductive health interventions in conflict settings: a systematic review,” BMJ Global Health, vol. 5, Suppl. 1, (Jul. 21, 2020): https://gh.bmj.com/content/bmjgh/5/Suppl_1/e002206.full.pdf. Although the SRH needs of men and boys in NWS merits study, this report focuses on the needs of women and girls, who are disproportionately impacted because of the social and economic situation in NWS.

[13] Many important issues related to SRH are implicated by, but lie outside the scope of, this study, including a full evaluation of the impact of violence on decision-making, autonomy, and health outcomes for SRH.

[14] UNOCHA, “Northwest Syria Funding Gap Analysis,” Jul.–Sep. 2021, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/20210701_funding_gap_analysis_all_clusters_final.pdf.

[15] UNOCHA, “Northwest Syria Funding Gap Analysis,” Jul.–Sep. 2022, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/nws_funding_gap_analysis_july_to_sep_2022_final_14072022.pdf.

[16] UNOCHA, “Northwest Syria Funding Gap Analysis,” Oct.–Dec. 2022, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/nws_funding_gap_analysis_oct_to_dec_2022.pdf.

[17] As noted in endnote 10, while a deep analysis of such social and cultural practices lies outside the scope of this report, the topic merits further study.

[18] Paragraph 39 (f) of United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, “Concluding observations on the second periodic report of the Syrian Arab Republic,” Jul. 24, 2014, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/778824; for the prohibition on abortion, see articles 524-529, 532, and 544 of The Syrian Penal Code 148 of 1949 (amended by Legislative Decree 1 of 2011) which apply to those who seek, cause, or perform an induced abortion, available at http://www.parliament.gov.sy/arabic/. Respondents also noted the limited conditions under which abortions may be performed to save the life of the mother. See, e.g., CBI #6, Female, Urban Aleppo, Medical.

[19]A practical example of this definition of awareness can be seen in the publication International Rescue Committee, Access to sexual and reproductive health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed methods assessment, May 2022, https://www.rescue.org/sites/default/files/document/6817/srh-bangladesh.pdf.

[20] Although the Cairo International Conference on Population and Development of 1994 (ICPD, paragraph 7.2), first provided a global policy framework for reproductive rights, the right to sexual and reproductive health was incorporated in the Nairobi Statement (ICPD+25). For a detailed discussion of the components of SRH rights, see Ann M. Starrs et al., “Accelerate progress—sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission,” The Lancet, vol. 391, no. 10140, (Jun. 30, 2018): 2642–2692, https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0140-6736%2818%2930293-9.

[21] World Health Organization, “Attacks on health care initiative: Documenting the problem,” Jul. 22, 2020, https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/attacks-on-healthcare-initiative-documenting-the-problem.

[22] The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) is a multi-ethnic alliance of Kurdish and Arab militias. It is led by the Syrian Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) and is heavily dominated by Kurdish fighters. See Al Jazeera English, “Who are the Syrian Democratic Forces?,” Oct. 15, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/10/15/who-are-the-syrian-democratic-forces/.

[23] For more information, see Annex I (Methods).

[24] IRC led one-day training sessions for data collectors to establish research ethics and principles and familiarize the staff with the questionnaire, data collection protocol, and data management/protection considerations. In addition, the training explained SRH concepts and sensitivities. Two data collectors were present in each interview: one data collector asked questions and the other transcribed the interview if participants did not consent to recording.

[25] Humanitarian Needs Assessment Programme (HNAP) Population Baseline Data NWS, Nov. 2022, on file with authors.

[26] Note that a different methodology was employed to produce this number. See page 16: “There is reason to believe that violations against international law were … committed, and … investigators [should] explore further whether crimes against humanity or war crimes have taken place” of Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), “Report limitations,” A Heavy Price to Pay: Attacks on Health Care Systems in Syria 2015-2021, May 2022, https://www.sams-usa.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/202205-SAMS-A-heavy-price-to-pay_Final_Version_En-1.pdf.

[27] SAMS, “Impact of attacks,” A Heavy Price.

[28] UNOCHA, “North-west Syria Situation Report,” Key Figures, as of Jan. 31, 2023, https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/northwest-syria-factsheet-21-september-2022.

[29] Ibid.

[30] World Health Organization, “Health Resources and Services Availability Monitoring System HeRAMS – Third Quarter, 2022 Report – Türkiye Health Cluster for Northwest of Syria, Jul – Sep 2022,” Jan. 10, 2023, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/herams_q3_2022_final.pdf.

[31] UNOCHA, “Humanitarian Needs Overview: Syrian Arab Republic,” Dec. 2022, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/hno_2023-rev-1.12_1.pdf.

[32] UNOCHA, “Northwest Syria Factsheet: As of 21 September 2022,” Sep. 22, 2022, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/northwest_syria_key_figures_factsheet_20220921.pdf.

[33] World Food Programme, “Syria Country Office Market Price Watch Bulletin,” Aug. 2022, https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000142857/download/.

[34] KII #40, Male.

[35] CBI #26, Male, Rural Aleppo, Medical.

[36] FGD #21, Urban, Atareb, Aleppo.

[37] For more information, see Annex III (Availability of Selected Reproductive Health Services in Northwest Syria).

[38] For a description of the MISP, see Inter-Agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises, “Quick Reference for the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH),” May 16, 2022, https://iawg.net/resources/misp-reference.

[39] For a history and analysis of the MISP and its effectiveness, see Monica Adhiambo Onyango, Bretta Lynne Hixson, and Siobhan McNally, “Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for reproductive health during emergencies: Time for a new paradigm?,” Global Public Health, vol. 8, no. 3, (Feb. 11, 2013): 342–356, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23394618/. Note that while the MISP does not address all aspects of SRH care as defined by the WHO, it aims to provide SRH in crisis settings and as such can be the basis for future expanded care. In NWS, a comprehensive SRH plan is being developed that is hoped will provide expanded services beyond the MISP. Telephone communication, Co-lead of the SRH TWG, Gaziantep, Türkiye, Jan. 26, 2023.