Executive Summary

A cornerstone of President Donald Trump’s campaign in 2016 was to portray immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers as a danger to the United States. Since taking office in January 2017, President Trump has continued such inflammatory rhetoric, deriding the U.S. asylum system as a “big fat con job” and accusing asylum seekers of exaggerating the violence they are fleeing.[1]

President Trump’s administration has matched that rhetoric with a hardline immigration policy agenda that targets people seeking asylum in the United States and obstructs the internationally and domestically recognized right of all people to seek asylum protection.

In the face of an array of restrictions, as of August 2019, an estimated 60,000 asylum seekers[2] were waiting along the southern border for the opportunity to exercise their right to seek asylum. Roughly one third of them were in Tijuana, Mexico. Drawing upon its experience providing forensic evaluations for thousands of asylum seekers in the United States over the past 30 years, PHR documented the cases of 18 asylum seekers waiting in Tijuana to assess the degree to which physical and psychological findings corroborate their allegations of abuse and persecution. This report is a compilation and analysis of those evaluations.

Explore the Stories of Asylum Seekers Fleeing Violence in Mexico and Central America

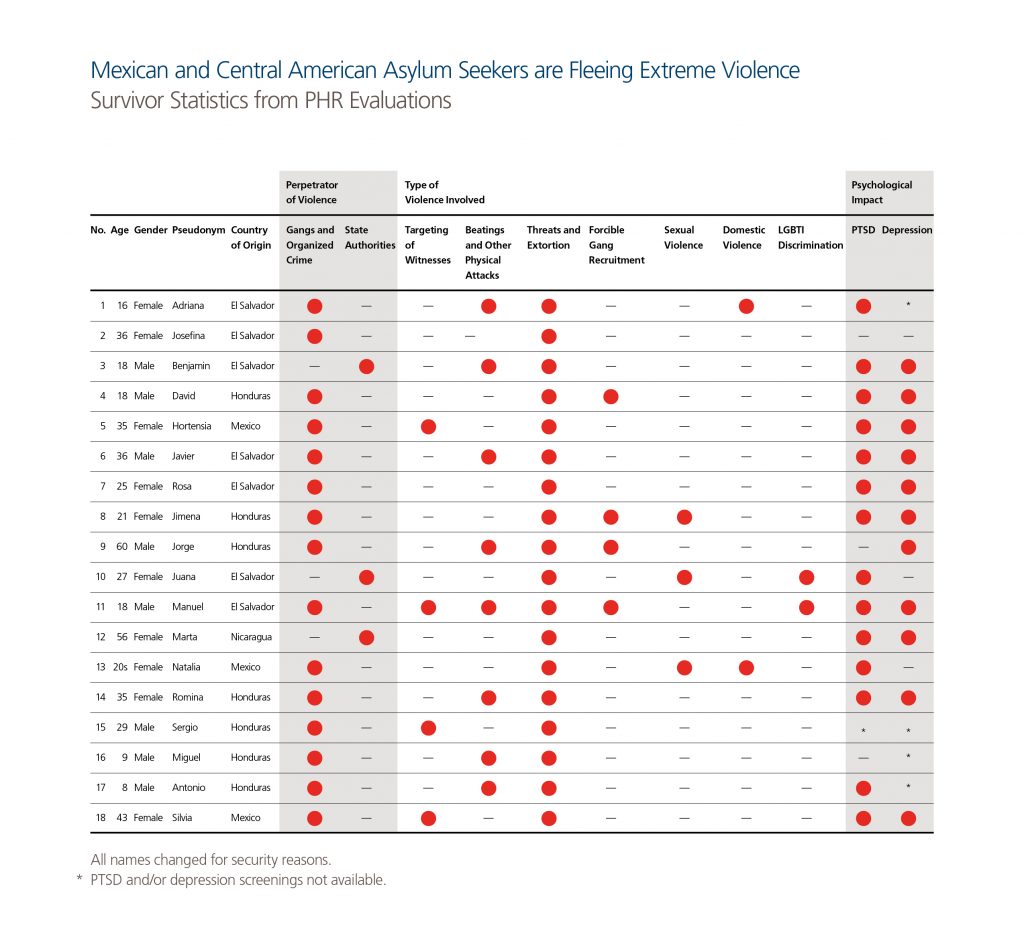

This report examines the cases of 18 asylum seekers (15 adults, three minors) from Mexico and Central America: El Salvador (seven), Honduras (seven), Mexico (three), and Nicaragua (one). While not meant to be a representative sample, these cases provide a snapshot of these asylum seekers’ lives and histories, why they undertook treacherous journeys to seek protection in the United States, and the physical and psychological impact that their experiences have had on them. All of the evaluated asylum seekers provided credible accounts and corroborating evidence that they fled persecution resulting in significant trauma. Several of these asylum seekers endured multiple forms of persecution and trauma, reflecting the compounding violence in several countries that drives so many from this region to seek asylum.

Out of the 18 asylum seekers PHR medical experts interviewed and clinically evaluated, three faced violence perpetrated by state actors, such as police and security forces. The remaining 15 were targeted by non-state actors, such as gangs who pursue specific groups of people. For example, every young male whom PHR interviewed in Tijuana reported experiencing pressure to join a gang. These gangs routinely forcibly recruit youth to carry drugs or collect “protection money” in neighborhoods where they have a stronghold. Those who do not comply face violence in the form of beatings, kidnappings, and killings. Women risk sexual violence if their partner does not comply with a gang, or they do not agree to become a “girlfriend” to one of its members. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex individuals also face threats, arbitrary arrests, killings, and other violence by state and non-state actors.[3] Because governments in the countries of origin lack the will or ability to protect people from these abuses, a bid for asylum often becomes the sole means for people to escape the possibility of deadly violence.

PHR further found that U.S. policies have stranded asylum seekers in Tijuana, where they are vulnerable to violence, theft, and extortion by cartels, gangs, and police authorities. Current U.S. asylum policies that restrict asylum seekers’ right to enter the United States inflict further trauma on them every day they must wait. Many of those interviewed by PHR reported feeling under imminent threat both during their journey to the U.S.-Mexico border and while they waited in Tijuana. Twelve out of the 15 adults interviewed screened positive for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and many who screened positive for depression also experienced fear and hypervigilance. Two out of the three children interviewed reported symptoms of PTSD, and one boy also showed signs of anxiety disorder and somatization, whereby psychological distress manifests as physical ailments and attention problems.

Current U.S. asylum policies that restrict asylum seekers’ right to enter the United States inflict further trauma on them every day they must wait.

PHR’s findings provide a compelling argument for the U.S. government to allow asylum seekers to apply for asylum in a prompt and fair manner and demonstrate how restrictive policies are likely to compound the stressors suffered by this already traumatized group of people. PHR asserts that the U.S. government should immediately stop impeding the internationally recognized right to seek asylum. Specifically, the US government should: 1) abolish the “metering” system which limits the number of people allowed to enter the United States each day to make their case for asylum; 2) ensure that the asylum application process is safe, predictable, and transparent; 3) end all practices, such as the Migrant Protection Protocols (which require applicants to return to Mexico to await their court date), intended to bar or deter asylum seekers from seeking protection in the United States; 4) cooperate with regional and international monitoring mechanisms from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the United Nations; and 5) guarantee that human rights defenders, medical personnel, and legal and humanitarian organizations serving asylum seekers do not face arbitrary restrictions for their work.

“This is a health and human rights crisis that is being treated as a border security crisis.”

Ben McVane, MD, PHR Asylum Network member and assistant professor,

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Methodology

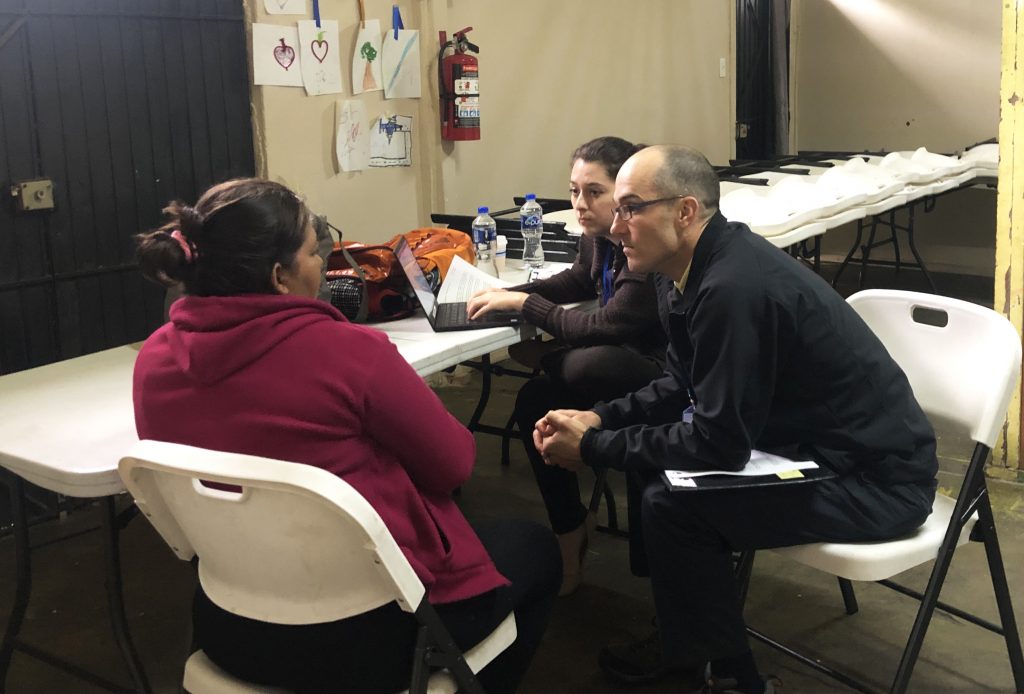

For more than 30 years, PHR has provided forensic evaluations for asylum seekers fleeing persecution. Based on the Istanbul Protocol [4] – the international standard to document alleged torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment – these forensic evaluations assess the degree to which physical and psychological findings corroborate allegations of abuse.

In February 2019, PHR staff worked with migrant shelters and a legal aid organization in Tijuana, Mexico to identify asylum seekers who had physical scars or psychological distress/harm as a result of violence which led them to flee. PHR screened 35 asylum seekers – six were unable to undergo evaluations due to logistical constraints, four did not fit the eligibility criteria, and two declined to participate. PHR-trained medical professionals produced 23 detailed and consistent clinical evaluations, which are modified versions of a forensic evaluation – 18 of these asylum seekers are from Mexico and Central America, four from Cameroon, and one from Iraq.

PHR Clinical Evaluations

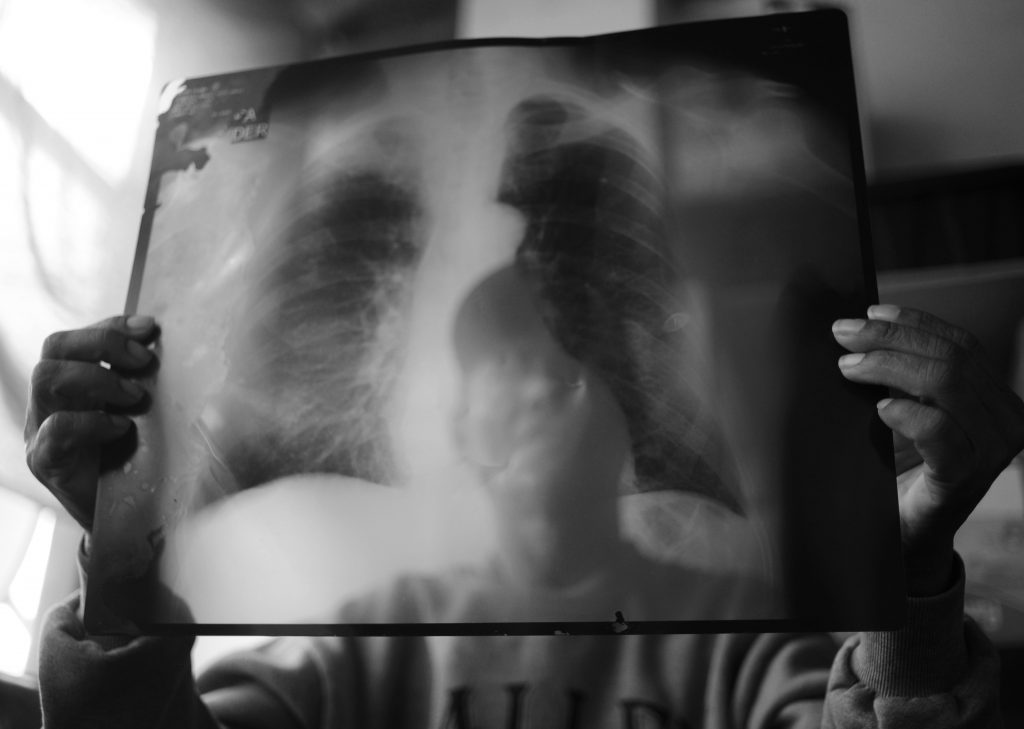

PHR created and applied a three-part clinical evaluation tool for adult asylum seekers for its research in Tijuana: a semi-structured interview documenting the event that drove the person to seek asylum; a physical exam of reported injuries [5] and available medical records; a PC-PTSD-5 psychological questionnaire to assess the presence of post-traumatic stress disorder; and a PHQ-9 questionnaire to assess the presence and severity of depression. Both mental health questionnaires have been independently validated and shown to have high sensitivity and specificity. PHR only interviewed minors between the age of seven and 17 accompanied by at least one parent with informed consent of each parent present and the child. These interviews were conducted by PHR clinicians with expertise in pediatrics and/or clinical psychology.

PHR-trained medical experts conducted clinical evaluations in Spanish or English, with the assistance of interpreters, when needed. Following an explanation of PHR’s work and the purpose of the investigation, PHR obtained verbal and written informed consent from each interviewee. All participants were informed that a clinical evaluation was not a formal evaluation of their asylum claim and received PHR’s contact information so that if/when the interviewee makes a formal claim in the United States with legal representation, they can request a full forensic evaluation to support their case.

PHR’s Ethics Review Board provided guidance and approved this study based on regulations outlined in Title 45 CFR Part 46, which are used by academic Institutional Review Boards in the United States. All PHR’s research and investigations involving human subjects are conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 2000, a statement of ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects, including research on identifiable human material and data.[6]

Cases from Mexico and Central America

To highlight the plight of asylum seekers from this specific region, this report draws upon the 18 cases from Mexico and Central America: El Salvador (seven), Honduras (seven), Mexico (three), and Nicaragua (one). These are 15 adults [7] (nine females, including one transgender female, and six males) and three minors under the age of 18 (one female, two male). For safety and confidentiality, PHR replaced the names of asylum seekers with pseudonyms and uses only deidentified photographs. PHR also omitted from several cases identifying information such as occupation, ages/number of children, dates of flight, and town within country of origin, among other details that could compromise anonymity.

Introduction

The United States recognizes the right of individuals to seek protection from persecution in accordance with federal and international laws. Under U.S. law, an asylum seeker must show that he or she is unable or unwilling to return to his or her home country and cannot obtain state protection there due to past persecution or a well-founded fear of being persecuted in the future “on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.”[8]

In the United States, U.S. Customs and Border Protection historically has been responsible for processing border crossers and then referring those who are afraid to return for a credible fear interview. In that interview, a U.S. asylum officer asks a series of questions to determine whether the asylum seeker faces a “significant possibility”[9] of persecution in their country.[10] Asylum seekers must demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution related to at least one of the protected grounds listed above. In addition, they must demonstrate either that the state is responsible for the persecution they are facing or that the government or state institutions are unwilling or unable to protect them from persecution by non-state actors, such as gangs.[11]

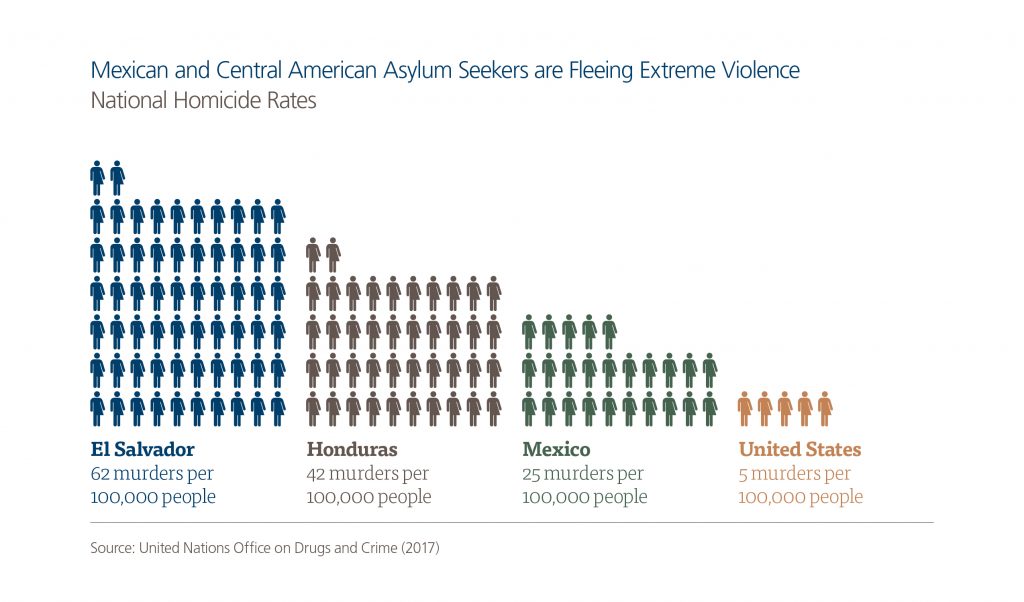

The Trump administration has decried the U.S. asylum system as an immigration “loophole” that is “being gamed,” suggesting that those who seek asylum do not have a well-founded fear of persecution, [12] and that the asylum system itself acts as a pull factor for migration. However, this narrative ignores violence and failed governments who are unable or unwilling to protect their people as a major factor pushing asylum seekers in Mexico and Central America. Despite a recent drop in homicide rates, El Salvador remains one of the most violent countries in the world, with 62 murders per 100,000 people, [13] almost 12 times the U.S. rate. Two thirds of these murders are gang-related.[14] While Honduras halved its homicide rate in 2018, it still stood at 42.8 per 100,000 people in 2017, [15] and eight violent massacres took place in the country in the first two weeks of 2019 alone. [16] Similarly, Mexico also experienced the deadliest year on record in 2018 [17] and the first three months of 2019 showed a 10 percent increase in homicides when compared to the same period in 2018. [18] Finally, the Nicaraguan government’s crackdown on the opposition in the form of arbitrary arrests, killings, beatings, torture, and sexual assault has forced at least 60,000 people to flee the country since April 2018. [19]

The target, nature, and extensive reach of violence and impunity in this region have given entire families and specific groups no alternative but to flee north in search of safety.

Some groups are particularly at risk: Central American youth are 10 times more likely to be killed when compared to children in the United States[20] as they become victims to gangs, state security forces, and organized crime. Gangs especially seek out young recruits, as they can more discreetly smuggle drugs and weapons, or collect extortion payments.[21] Taxi drivers often are forced to carry illicit goods or act as informants in neighborhoods controlled by rival gangs. [22] Women are especially vulnerable: two out of three women killed in Central America [23] are murdered solely because of their gender, a pattern of violence known as “femicide.”[24] Those who resist forced prostitution and/or becoming sexually enslaved by gangs risk being killed.[25] The LGBTI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex) community also faces threats, arbitrary arrests, killings, and other violence by state and non-state actors.[26]

The target, nature, and extensive reach of violence and impunity in this region have given entire families and specific groups no alternative but to flee north in search of safety. Tragically, these groups have come into the crosshairs of the Trump administration’s restrictive policies. Although many of these attempts have been struck down as unlawful, they have nonetheless had an impact on thousands of asylum seekers and prevented bona fide refugees from accessing their legal right to seek protection. For example, the increase in denial rates in the second half of 2018 corresponds with then Attorney General Jeff Sessions’s effort to limit the grounds on which immigration judges could grant asylum, making it increasingly difficult for those with domestic violence and gang violence claims to gain protection.[27] In December 2018, U.S. District Judge Emmet Sullivan ruled that each asylum claim must be considered individually and the government cannot impose blanket denials on asylum seekers.[28] Had Sessions’s decision prevailed, thousands of asylum seekers, including eight of the 18 cases included in this report, would no longer be eligible for asylum protection.[29]

The cases below tell the stories of young men who fled forced recruitment into gangs, women and girls who faced sexual and gender-based violence, and families who could not pay protection money to stay alive. PHR medical experts collected testimonies and conducted clinical evaluations to illustrate how violence unfolds in this region and demonstrate how already vulnerable and traumatized people risk being further harmed by restrictive U.S. policies that deny them the right to protection.

Findings: Asylum Seekers Are Fleeing Violence and Impunity

“There were two to three people killed every day in the neighborhood…. My elementary school friend was killed inside a car the same day she was going to give birth. There are so many killings now. At first, we could go to wakes, but now we cannot even go to pay our respects to a friend or family member. They already killed three of my nephews.”

Silvia, 43-year-old woman, Mexico

All cases in this report tell the stories of asylum seekers who sustained violence in their country of origin that led to physical scars and/or psychological symptoms resulting from violence or serious threats of violence. Physicians for Human Rights’ (PHR) findings describe multiple forms of violence perpetrated either by state actors, such as corrupt police officers (three cases), or by non-state actors, such as gangs and organized crime (15 cases). [30] This violence included beatings, rape, and murder. Many of the people who were targeted by gangs and organized crime described how government authorities in their country failed to protect them from the violence. [31]

Seeking Asylum with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a complex syndrome of somatic, cognitive, affective, and behavioral symptoms that results from the psychological trauma of direct or indirect violence or threats to life.[32] While studies show that asylum seekers who have suffered trauma also demonstrate impressive resilience and are often able to securely resettle their lives once in safety,[33] PTSD can impair asylum seekers’ ability to cope with physical challenges on the journey, and the cognitive effects can adversely impact an individual’s likelihood of obtaining asylum.

Historically, to be granted asylum in the United States, or even to pass the initial “credible fear interview,” an asylum-seeker must make a qualifying claim in a manner that is detailed and specific and demonstrates a “significant possibility” of persecution in their home country. Given the frequent lack of corroborating witnesses or physical evidence, internal consistency in the narrative becomes crucial. However, scientific studies have shown that the trauma narratives presented by PTSD patients are consistently rated as more disorganized than non-trauma narratives of these same patients or the trauma narratives of individuals without PTSD.[34],[35] Asylum seekers often also have more difficulty recounting their story the longer they have to wait.[36] From a clinical perspective, this additional time is likely to impact asylum seekers’ ability to build a consistent claim, which affects their ability to exercise their right to apply for asylum.[37]

PHR’s mental health evaluations included the administration of validated screening tools for PTSD, anxiety, and depression. Results of these clinical evaluations showed that 12 adults screened positive for PTSD. Similarly, 11 adults screened positive for depression; seven of them exhibited signs and symptoms consistent with moderately severe to severe depression. All but one asylum seeker reported that they “tried hard not to think about the event(s) or went out of their way to avoid situations that reminded them of the event(s),” and 15 of them reported experiencing nightmares or unwanted thoughts. For example, Javier (Case 6), a 36-year-old man who was extorted and beaten by a gang in El Salvador, reported symptoms of PTSD, severe depression, and anxiety. His inability to sleep led to physical exhaustion and lack of focus. He also felt constantly on guard and watchful. “Having seen so much violence, sometimes I start shaking … a kind of fear,” he said. “My body begins shaking and I go cold.”

Recounting a traumatic event may induce distressing symptoms. Thus, asylum seekers with PTSD may not share all details of their experiences, diminishing their capacity to effectively make their case. Moreover, an asylum seeker may seek to demonstrate resilience and avoid relaying the most central cause of what led them to seek protection, only bringing it up at the end of their narrative, possibly preventing its full elaboration or unintentionally diminishing its importance. For example, Juana (Case 10), a transgender woman who was sexually violated in El Salvador, only told PHR about the assault that prompted her to seek asylum towards the end of her interview. Similarly, the PHR medical expert who examined Jorge (Case 9), a 60-year-old Honduran whose clavicle was broken by gang members who attacked him with a baseball bat, said Jorge “often seems to intentionally withhold the most difficult parts of his experiences to hide embarrassment and demonstrate his positive attitude.”

“Having seen so much violence, sometimes I start shaking … a kind of fear…. My body begins shaking and I go cold.”

Javier, 36-year-old man, El Salvador

Violence by Non-State Actors: Gangs and Organized Crime

PHR documented 10 cases that involved gang violence. They were all consistent with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) definition of who gangs target and how this violence forces people to flee:[38] forcible youth recruitment into gangs; extortion of small business owners and other specific groups unable or unwilling to pay protection money or provide certain goods and services; threats or killings of witnesses to crimes, or those who have reported crimes; and gender-based violence toward women and girls, among other groups.[39]

As the cases below demonstrate, gangs have a “high level of organized determination as to who should be killed, when and where,”[40] and these are not “random criminal acts.”[41] Moreover, PHR’s research found that in six of the 10 cases related to gang violence, the asylum seekers tried to find a safe haven in their own country or another country before fleeing to the United States, but continued to face insecurity given the gangs’ stronghold. As Manuel (Case 11), an 18-year-old man who fled gang recruitment in El Salvador, explained to PHR, “the country is so small that there are gangs in every corner and in all neighborhoods.”

“They said that they wanted soldiers, people who would work for them … youth.”

Manuel, 18-year-old man, El Salvador

Forcible Recruitment of Youth to Gangs

PHR documented five cases involving the forcible recruitment of youth to gangs.

Salvadoran brothers Manuel and Daniel were home when gang members showed up to pressure Daniel into joining the gang, which he had already refused to do. They took Daniel away, and the next day, his body was found in a canal, strangled with his own shoelaces. Manuel believed that the gang had planned to recruit Daniel, then Manuel, then his other brothers: “They were going to take us one by one.” Because he had witnessed Daniel being taken away by the gang members, Manuel became a target.

“I fled because I knew who was responsible and they were going to take my life. They were looking for me to kill me.”

Manuel, 18-year-old man, El Salvador

Sexual Violence as a Weapon for Recruitment

Women also become targets within the context of forcible recruitment. Jimena (Case 8), a 21-year-old woman from Honduras, was two months pregnant and had a toddler with her husband, Jose (Case 9). He worked at a private security firm and knew how to handle firearms, so a gang repeatedly asked him to join, but he always refused. One day, gang members beat him and told him that they would kill him or “hurt where it would hurt the most” if he did not join.

A few days later, two armed men came to Jimena’s home when she was alone. They threw her on the kitchen floor face down. As she fought back, one of the men kneeled by her head and held her down by the shoulders, while the other man raped her. The whole time she was terrified of losing her baby. Before leaving, the men said they would kill Jimena, her child, and Jose if he did not report to a specific location. The family immediately fled to another town in Honduras. Two months later, while Jimena’s cousin was visiting, two men drove by on a motorcycle and shot the cousin nine times, killing him instantly. Jimena and her husband interpreted his killing as a message from the gang that it had found them and that their lives were in imminent danger.

That same day, Jimena and Jose began the five-month journey to Tijuana; Jimena gave birth to their new baby along the way. She described to PHR her physical state after the rape: “I had bruises on my shoulders where they held me down. I had pain in the abdomen for three days and in my stomach throughout the pregnancy; it hurt to sit down.”Jimena showed signs of depression and PTSD, including hyper vigilance and avoidance of situations that remind her of the gang members who raped her.

Extortion and Threats

Two out of the 10 asylum seekers who faced threats and/or violence from gangs or cartels reported that extortion in the form of demands for protection money was the reason they fled their countries. Estimates suggest that gangs in El Salvador and Honduras collect more than $300 million each year,[42] demonstrating the widespread nature of this practice in both countries.[43] Gangs target specific occupations, such as small business owners, transportation workers, or anyone who is known to have some steady income or can provide them with a needed service.[44] For example, one interviewee explained to PHR how the system works: “They say that they protect you from other gangs…. A young boy 13 or 14 years old will arrive and give you a phone, and someone on the other end tells you that you have to pay and if you do not comply, you will see what happens. And we know how they kill people for not paying, you hear about it daily…. They can increase it as they see fit and one can only say ‘yes.’”

“They said that this was a warning but next time they would kill all of us. That is why we left in the middle of the night. We do not feel safe. They are not playing games.”

Javier, 36-year-old man, El Salvador

Demands for Protection Money Turn Deadly

Javier (Case 6), a delivery man for a bakery in El Salvador, described how he was targeted for protection money because of his profession. He diligently paid roughly one eighth of his income every month to the gang until, one month, his earnings fell short. Two days past the payment’s due date, gang members beat Javier as a warning to pay up and not delay again. They punched and kicked him in the chest, shoulders, and back. He was only able to cover his face and did not fight for fear of being shot and killed. That same night, Javier and his family fled El Salvador.

“They said that this was a warning but next time they would kill all of us. That is why we left in the middle of the night. We do not feel safe. They are not playing games.”

Javier, 36-year-old man, El Salvador

Transportation Workers Are Targeted

Silvia (Case 18) described to PHR how her husband, a taxi driver, was forced to pay protection money to an organized crime group in southern Mexico, which later escalated to using his taxi to transport members. They reportedly told him and his fellow drivers: “We have your names and phone numbers. We know each one of you, where you live, and you can no longer decide for yourselves. If one of us asks you to take us somewhere, you have to do so. The first time you refuse, we will beat you until you bleed. The second time … there will not be a second time because we will just shoot you with bullets.”

Silvia reported that, one morning, organized crime members told her husband to drive them to an area dominated by a rival group. They said, “You already have a bullet in your head anyway; it is better that you just take us.” As they drove, Silvia’s husband heard them speaking about the people they planned to kill and then he realized that the rival groups had planned a duel. Silvia’s husband managed to escape the crossfire unscathed but knew he would now be a target for both groups. Shortly afterwards, he, Silvia, and their children fled.

Silvia screened positive for depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. She described her nightmares as full of: “fear, terror, dread, panic. I wake up from nightmares and start to pray, asking God to help and protect me…. I dream that they kill my kids.… I dream that they muzzle everyone, and I scream.”

“If one of us asks you to take us somewhere, you

Silvia, a 43-year-old woman from Mexico, quoting organized crime members who threatened her husband, a taxi driver

have to do so. The first time you refuse, we will

beat you until you bleed. The second time … there

will not be a second time because we will just

shoot you with bullets.”

Killings and Witness Elimination

PHR documented cases in which witnesses to crimes were targeted by gangs and other forms of organized crime, such as cartels or paramilitary forces. For example, Silvia (Case 18) described to PHR that, in her neighborhood in Mexico, “when there are witnesses [of crimes], they have to kill all of them. This is where the hitmen come in – youth on motorcycles who go on a shooting spree.” Days after one of Silvia’s neighbors denounced a relative’s murder, her husband was shot as they swept their backyard. Another neighbor was killed simply after he saw local cartel members running across rooftops near his home.

Entire Families as Targets

Hortensia (Case 5), a 35-year-old woman from southern Mexico, told PHR that she and her family fled their home after her father was killed. They still did not know why exactly her father was targeted, but Hortensia could only assume that his small ranch was seen as a resource. Hortensia recounted that her father had started receiving threatening phone calls, and a name similar to his then appeared on a death list posted on social media. These did not worry him, however, as he did not owe anyone anything.

On the day of her father’s killing, Hortensia reported that she and some relatives were at her siblings’ shop when some cars stopped on the street. Several young men jumped out and ordered everyone to put their head down. They then moved toward her father and took him, threatening everyone else if they moved. That evening, Hortensia’s sister received a text message with a picture of her father’s beaten body with eight bullet wounds, one of which was lodged in his eye. A couple of days later, Hortensia’s sister received a threatening phone call saying that the whole family would be next. They were left notes that said, “Leave now and do not get yourself into problems.” Three days after they buried Hortensia’s father, the entire family left for Tijuana.

In Honduras, Sergio (Case 15) worked with a farmers’ collective and began suspecting that some members were using the collective to launder money, buy arms, and carry out land evictions. He and his wife, Romina (Case 14), told PHR how one day he was driving his motorcycle on a road and stopped because he heard gunshots. He then saw the dead body of a child. The men at the collective were convinced that Sergio had seen the killers and threatened to kill him. Other acquaintances told him he was a target because he “knew too much” and a member of the collective said to Romina “They are going to kill him anyway. Just turn him in [to us].”

Shortly afterwards, Sergio, Romina, and their son Antonio (Case 17) were riding their motorcycle, when two men on another motorcycle drove up to them and tried to strike them with a machete, missing the eight-year-old boy by just a few centimeters. With assistance from a local human rights organization, the family fled to another town and then crossed the border to Guatemala. They spent two months there before traveling to southern Mexico and later on to Tijuana. Romina still struggles with the trauma of what they experienced: “I feel pressure about everything … my kids, my husband, myself, and the family I left behind in Honduras,” she told PHR. “I am so anguished that I cannot concentrate on anything. I think to myself, ‘I cannot go on’ and then I become short of breath. Twenty minutes later I faint. My head hurts.”

PTSD in Children

One of the children interviewed in Tijuana was Antonio (Case 17), an eight-year old Honduran boy who was attacked by two men with a machete. His attackers missed killing Antonio by just a few centimeters when they hurled the weapon at the boy as he rode on the back of a motorcycle with his parents. Antonio’s experience of violence in Honduras has contributed to signs and symptoms of PTSD and anxiety disorder.

Antonio’s favorite school subject was writing, and he enjoyed playing ball with his friends back in Honduras. But when PHR asked him how he felt about returning to his country, he replied, “I am afraid. I think something would happen to me. I think they would kill me and my parents.” PHR’s medical expert recorded that, since he witnessed violence, Antonio has become sad and cries often. He often holds his breath when he is afraid and often must hold his mother’s hand to be at ease. His parents told PHR that, since he arrived in Tijuana, Antonio often defecates in his bed and suffers from nightmares where he yells in his sleep, “Mom, hurry! Hurry! The guy is going to kill us!” His mother said that Antonio is scared until they comfort him and put him back to sleep. Antonio reported symptoms of PTSD and anxiety disorder as well as somatization, whereby psychological distress manifests as physical ailments and attention problems.

Since arriving in Tijuana, Antonio has not had access to mental health care. Antonio has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; the family does not have adequate medication for him while they wait in Mexico, and this lack of medication is likely to exacerbate his condition. Antonio’s mother explained to PHR her concern for her children’s future: “I still don’t see it [ending]…. I want my children to be OK in a safe place … but we have not found that [safety] yet. Our hope is that they will give us asylum, so my kids will be safe on the other side.”

“I am afraid. I think something would happen to me. I think they would kill me and my parents.”

Antonio, eight-year-old boy, Honduras

Violence by State Actors and the Failure to Protect

Asylum seekers must demonstrate that

the state is responsible for the persecution they are facing or demonstrate

that their government or state institutions are unwilling or unable to protect

them from the persecution of non-state actors such as gangs.[45]

The three sections below draw upon PHR’s cases to illustrate how violence

carried out by the state and/or its failure to provide protection from non-state

actors has left many asylum seekers in Mexico and Central America with no

options but to flee.

State Violence

States are mandated to protect their populations from violence, but corrupt authorities are too often directly involved in human rights violations in Mexico and Central America. PHR documented the three cases below of state actors as direct perpetrators.

Silenced for Her Political Dissent

In Nicaragua, after three consecutive terms in power, President Daniel Ortega faced mass protests in April 2018. A brutal crackdown by police and armed pro-government groups resulted in arbitrary arrests, killings, beatings, torture, and sexual assault.[46] As of April 2019, more than 60,000 Nicaraguans had fled to other countries in search of refuge.[47] Marta (Case 12) is one of these cases.

Marta participated in the first protests in April 2018. Soon after, police officers arrived at her home, accusing her of supplying protestors with explosives because her sister owned a former fireworks workshop. The police raided Marta’s home and found nothing, but vowed to return. When protests broke out in July 2018, Marta stayed home due to a foot injury. She was sweeping her front yard when government supporters almost ran her over. She yelled at them, and, three hours later, police officers and anti-riot forces surrounded her home, accusing her of assaulting the government supporters.

She told PHR, “I felt that they were going to burn my house with me inside. I felt a horrible sense of fear.”Eventually the security forces left, and she never slept another night in her home.

Neighbors told her that from that moment, the police returned at least every other day, threatening that Marta would “pay for what she had done.” A week later, three men approached her, saying that they “wanted her head,” so she fled Nicaragua with her 23-year-old son.

“Most young men are returned [to their families] dead in black bags. And even those are lucky because they often kill the family, too. If I went back to El Salvador, I would not survive.”

Benjamín, 18-year-old man, El Salvador

Profiled as a Gang Member

El Salvador’s state security forces have instituted harsh anti-gang tactics that routinely involve excessive use of force, arbitrary arrests, and extrajudicial executions.[48] They conduct raids without warrants on homes of young Salvadoran men who have been profiled as suspected gang members due to their gender, age, and neighborhood.[49] Police officers wearing uniforms from El Salvador’s elite anti-gang unit took 18-year-old Benjamín (Case 3) from his home one afternoon. They drove for 30 minutes to a remote area, where the officers made him get out and kneel on gravel with his hands cuffed behind his back.

After beating him for hours and forcing him to put his fingerprints on a firearm, three officers drove Benjamín home and held him in the car while they searched his home. Benjamín suspected that they were trying to plant guns and drugs to falsely incriminate him. When his mother arrived, the officers told her that Benjamín was missing and suspected dead due to his alleged gang involvement. After interrogating his mother for hours to no avail, the officers let Benjamín go. Three days later, fearing that he would be targeted again, he fled north. Benjamín told PHR that he considers himself lucky. “Most young men are returned [to their families] dead in black bags. And even those are lucky because they often kill the family, too,” he said. “If I went back to El Salvador, I would not survive. I think it would be worse and they would finish me. I also fear for my family and my younger brother.”

Targeted for Her Sexual Identity

Juana (Case 10), a 27 year-old-transgender woman from El Salvador, faced widespread discrimination and persecution. Her family no longer spoke to her, and she could not get a job. Police officers often harassed her, pulling her long hair and telling her to cut it, or forcing her to do squats to “teach her to be more of a man.” One day, Juana was at a waterpark with a friend when two police officers stopped her and forced her into their car. She thought they were taking her to the station, but instead, Juana said, “They forced me to have sexual relations with them in the car.” When she threatened to report the incident, they replied “We hope you do. Then it will be worse for you next time,” demonstrating the lack of accountability of state security forces in El Salvador. After this traumatic event, Juana fled to Tijuana, sleeping in parks and gas stations along the way, as she had very little money. According to UNHCR, almost 90 percent of the LGBTI asylum seekers and refugees from Central America like Juana reported some form of sexual and gender-based violence in their countries of origin.[50]

Failure to Protect and Impunity

States fail to protect the population when government officials themselves are involved in human rights violations, and when they are unable or unwilling to provide protection from non-state actors. PHR documented how the lack of effective state protection leaves populations in Mexico and Central America at risk, and how this failure to protect influences people’s trust in state authorities. According to UNHCR, a state’s ability or willingness to protect can be assessed by analyzing the population’s willingness to seek assistance from authorities and whether this is perceived as futile or likely to increase risk of harm by gangs.[51] As Jorge (Case 9), a 60-year-old man from Honduras, told PHR, “We do not trust the police. They are part of the gangs. They get a percentage from the drugs they sell.” This sentiment was echoed by other asylum seekers as well.

“We do not trust the police. They are part of the gangs. They get a percentage from the drugs they sell.”

Jorge, 60-year-old man, Honduras

Fifteen asylum seekers interviewed by PHR – seven from Honduras, five from El Salvador, and three from Mexico – were targeted by non-state actors, such as gangs. For example, Javier (Case 6), the Honduran delivery-man whose case was highlighted above, explained to PHR why he decided to flee instead of asking the police for help: “They are linked. If one files a complaint, they themselves [the police] will pass on the information [to the gang].… We have seen people who have gone to testify and are dead in days.” Similarly, Manuel (Case 11), the 18-year-old Salvadoran who was being pursued by a gang, explained that: “It is all one corruption scheme, because in many neighborhoods they [gangs] pay the police to kill people whom they cannot [kill]. The gang pays the police to do the work of the gang.” Finally, Jimena (Case 8), who was raped in retaliation for her husband not joining a gang, told PHR why she did not go to authorities: “If I had told anyone, the gang members would have found out and killed me. If I had told police, this would have happened to me. They would have laughed. I knew a lot of people who filed reports, and this happened.”

“If you denounce a gang member, the police pass your information to the gang, and they make you disappear… A person gives testimony one day, and the next day they are dead.”

Javier, 36-year-old man, El Salvador

Gangs’ Pervasive Influence

Asylum seekers in Mexico and Central America are aware of how gangs exert influence over authorities, which leaves no recourse for protection. For example, PHR interviewed 16-year-old Adriana (Case 1), a girl who faced sexual and gender-based violence at the hands of her boyfriend, Pedro, whose brother was a gang member in El Salvador. In Adriana’s words, “He would always tell me that he would kill me if I did not go with him. He would not let me be with anyone else.… He told me that he would kill me and bury me.”

She also described how Pedro routinely sent her videos showing how gang members killed their girlfriends or forced them to dance naked on camera if they did not follow orders. He also would describe women being gang-raped or having objects forced inside them. When Adriana tried to leave Pedro, he used his gang affiliation to threaten her and her family, and he once beat her when she was 4-1/2 months pregnant, causing her to lose the pregnancy.

Concerned for her safety, Adriana’s mother once told Pedro that she was taking her daughter home. Given that Adriana was a minor, she threatened to involve the police. Pedro replied, “You do not know what you are saying. It appears that you do not love your family. They will all be gone if you open your mouth,” implying that his brother’s gang would retaliate. He later warned again that “blood would flow” if they tried to do anything. Knowing that this could very well happen, Adriana and her mother did not lodge a complaint and instead escaped to another town. They found out through neighbors that their house was then ransacked. As they continued to receive threats from the gang via social media, both mother and daughter felt unsafe and fled El Salvador entirely. Adriana’s case illustrates how authorities are not seen as willing or able to protect people from gang violence, and also serves as an example of a broader pattern in El Salvador, where every 19 hours a woman is killed and every three hours someone is sexually assaulted.[52]

Official Complaints Ignored

PHR interviewed some asylum seekers who did file complaints with authorities in their home countries. For example, Natalia (Case 13) is a mother of three in her 20s[53] who was a schoolteacher and dreamed of running a day care center. She told PHR that as her husband, Alejandro, became increasingly aggressive towards her and her children, he told Natalia that he was connected to drug trafficking and therefore she could not take action against him. When Natalia tried filing complaints with local law enforcement, she found Alejandro was right: nothing ever happened. Eventually, Natalia left him but he continued to verbally and physically abuse her and their children, at times showing up at her workplace with a gun. He also broke into her home and raped her.

Natalia reported to PHR that, one day, Alejandro took her children from her home just as she left for work. As he drove with the children, he found Natalia walking on the street and almost ran her over. Natalia told PHR that she heard the eldest boy screaming “Daddy, do not do anything to my mommy!” as Alejandro got out of the car and grabbed Natalia by the hair. He then dragged her to nearby train tracks, where he held her down and waited for a train. Natalia got away by biting his hand, but he warned her: “I have my boss’s permission to do anything. You will not escape, I will kill you. Do not even think of doing anything because the government is with us.” Natalia then escaped to another town, where Alejandro eventually tracked her down, saying: “I found you, bitch. You thought you would escape so easily from me? I already have someone who will buy you and your dirty children. You are going to see how you will suffer when they open up your kids,” referring to the fact that Alejandro had sold Natalia and the children to traffickers for their organs. She immediately sold as many her belongings as she could in one day and bought bus tickets that same night to go to Tijuana.

Law and Policy: The Right to Asylum under Assault in the United States

The Refugee Convention defines refugees as individuals “unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.”[54] The United States government enshrined the goals of both instruments in domestic law with the passage of the Refugee Act of 1980.[55]

The Refugee Convention[56] is based on the principles of non-discrimination, non-penalization, and non-refoulement (a French term meaning “non-repulsion” or “non-return”). These principles translate into basic parameters: States should not discriminate against asylum seekers based on any prohibited grounds, such as race, gender, or sexual orientation.[57] States should not penalize asylum seekers for crossing without valid entry documents or between ports of entry.[58] States should not return asylum seekers to a place where they could be subjected to “great risk, irreparable harm, or persecution.”[59] The principle of non-refoulement is also included in U.S. domestic law,[60] the Convention against Torture (Article 3),[61] and the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (Article 16).[62]

The U.S. asylum system has long been a complex process.[63] Since 2017, the Trump administration has proposed, adjusted, or implemented a series of restrictive policies that have made the process increasingly arduous for asylum seekers and hindered their legal right to seek protection. Those policies include family separation, prolonged detention under inadequate and harmful conditions, bans on eligibility for asylum, and other shifts in how credible fear interviews – the first step for those seeking asylum – are conducted and adjudicated, as well as the suggestion that asylum seekers should pay fees to apply for protection.[64] As discussed below, several of the Trump administration’s policies also may directly or indirectly violate the principle of non-refoulement by forcing asylum seekers to stay in locations where they may face harm and/or returning them to their countries of origin, where they also may experience further harm.

Creating Bottlenecks at the Border: The Practice of “Metering”

The practice of “metering” blocks timely access to asylum procedures. Created by the Obama administration in response to an increase in Haitian asylum seekers at the San Ysidro/Tijuana port of entry in 2016,[65] “metering” is a practice whereby Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers limit the number of migrants who can be processed at a port of entry in any given day.[66] Human rights organizations have argued that “metering” is illegal, filing a class action lawsuit in July 2017 to challenge this practice.[67] U.S. law does not specify any limit on the number of asylum seekers allowed entry into the United States to make a claim, and these individuals must be referred for inspection and processing upon arrival.[68]

CBP’s motion to dismiss this lawsuit against “metering” was denied in July 2019,[69] and the lawsuit was in litigation as of September 2019.[70] Since the lawsuit was filed, the Trump administration has expanded metering at ports of entry across the southern border. This has drastically reduced the number of asylum seekers who are inspected and processed per day. For example, the San Ysidro/Tijuana port of entry generally processed anywhere from 40 to 100 asylum seekers per day in 2018.[71] As of September 2019, roughly 25 people were processed by CBP each day, and there are more than 10,000 people on the waiting list in Tijuana awaiting their turn to cross and make a claim.[72] Data indicates that, as of August 2019, there is a backlog of 26,000 asylum seekers across Mexico on waiting lists to present themselves to U.S. authorities and make their claim for asylum.[73] This number does not include the thousands of others who have been returned to Mexico under the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP).

With few exceptions,[74] virtually all asylum seekers who present themselves at ports of entry along the U.S.-Mexico border are subject to the practice of metering before they can enter the United States. PHR documented the case of Natalia (Case 13), whose case is described in the above “Failure to Protect” section. When Natalia arrived at the U.S. border in Tijuana with her young children, she tried turning herself over to U.S. officials at the port of entry to claim asylum. However, Mexican authorities told her, “You have to get in line,” referring to the waiting list where thousands of asylum seekers have placed their name. With no food or money, Natalia eventually found a shelter where she spent at least two months waiting for the opportunity to make her claim to U.S. authorities.

Sending Asylum Seekers into a Dangerous Limbo: “Remain in Mexico” Policy

In December 2018, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) instituted the Migrant Protection Protocols.[75] Known as the “Remain in Mexico” policy, this protocol requires asylum seekers to await the processing of their case in Mexico, which obstructs their ability to access counsel and secure protection and leaves them vulnerable to violence, with no resources to move their claim forward. DHS has stated that the MPP was created so “vulnerable populations receive the protections they need,”[76] but this policy puts them at risk and violates the principle of non-refoulement.

Human rights groups have challenged the MPP in court. As of August 2019, however, the policy was expected to expand along the entire U.S.-Mexico border.[77] According to CBP, as of September 1, 2019, at least 42,000 asylum seekers have been returned to Mexico.[78] Human rights organizations state that MPP returnees include many vulnerable groups, such as seniors, children, pregnant women, and LGBTI individuals and people with disabilities who were meant to be exempt.[79]

“Returning asylum seekers to Mexico endangers their lives and is a catastrophic stressor to their health. The amount of time they spend waiting is often correlated with an increase in complex physical and mental health problems.”

Mary Cheffers, MD, PHR Asylum Network member and clinical faculty, University of Southern California

The MPP also is putting asylum seekers directly in harm’s way.[80] Gripped by a record rate of homicides in 2018, Mexico is beset by violence from gangs and organized crime that perpetrate extortion schemes, kidnappings, and killings – the very patterns of violence that Central American and other asylum seekers flee. [81] For example, David (Case 4) reported to PHR that he escaped forcible gang recruitment in Honduras by moving to Mexico, where his mother lived. While this country initially seemed safer for him, a group of men murdered David’ neighbors and warned him to leave, as he had witnessed the killing. A month later, the same men returned and told David that he had five days to leave. A close cousin had just been murdered in Honduras, so returning there was certainly not an option. David and his mother then traveled to Tijuana to try to seek asylum in the United States.

PHR interviewed several asylum seekers who faced violence while waiting in Tijuana.[82] For example, Manuel (Case 16) recounted how the same gang he had fled in El Salvador found him at a migrant shelter in Tijuana. When they saw him, several men threw Manuel into a tent and began beating him. As they threw punches, the gang members made phone calls to El Salvador to confirm that he was “the one.” When Manuel denied his identity, the men hit him harder on his chest with a metal rebar. During his interview with PHR Medical Expert Craig Torres-Ness, MD, Manuel recalls the ordeal: “I thought that at any moment I would lose my life.” The men also attempted to stab Manuel in the chest, but he was able to stave them off using his forearm as a shield. PHR’s clinical evaluation found that scars on Manuel’s chest and forearm were consistent with his report. Security at the migrant shelter intervened in time and Manuel escaped, then went into hiding in Tijuana while he awaited his turn to make a claim in the United States.

PHR documented other cases where asylum seekers faced threats or violence while in transit through Mexico. For example, Juana (Case 10) told PHR that on three occasions she was extorted by Mexican authorities, who told her that they would destroy her temporary visa unless she paid them money. Juana added that this sense of insecurity persisted even once she reached the border: “I do not feel safe in Tijuana. Gang members are everywhere; they can find us here and disappear us … I worry a lot. I’m not at peace. I feel like they can find us here at any moment and I do not know what could happen.” Benjamín (Case 3) also told PHR that he faced extortion throughout his journey, with local police officers falsely telling him that his visa was invalid. As Benjamín fled El Salvador because he had been kidnapped and beaten by the police, these interactions were particularly distressing: “Sometimes when I see police on the street, it reminds of the things I went through.”

“El Salvador has many gangs and they communicate with each other to search for people. I am in fear here [in Tijuana] too.”

Adriana, 16-year-old girl, El Salvador

Migrant Protection Protocols Obstructing Access to Legal Assistance

In addition to putting asylum seekers at risk, the MPP effectively blocks those remaining in Mexico from access to a U.S. lawyer. That legal assistance is essential for asylum seekers to adequately prepare to face an immigration judge; obstructing that aid has a deterrent effect on asylum seekers. From October 2016 to September 2017, courts/judges denied the claims of 90 percent of asylum seekers who lacked an attorney. However, judges and courts approved almost half of the claims of asylum seekers who had the benefit of lawyers.[83] For those who remain in Mexico, the prospects of assistance from a U.S. immigration lawyer are slim. As of June 2019, out of a total of 1,155 MPP cases that had been decided, only 14 cases (1.2 percent) had legal representation. Out of the 12,997 pending MPP cases, only 163 cases (1.3 percent) had legal representation.[84]

This lack of access to legal representation has affected how people are able to exercise the right to seek asylum. In February 2019, PHR interviewed Javier (Case 6), who fled extortion by gangs in El Salvador. When his metering number came up, Javier and his family went to their appointment with U.S. immigration officials. They were returned to Mexico under MPP. Given the lack of access to legal counsel, Javier felt that the system was stacked against him: “I do not know the laws in the United States. How will I represent myself? I take it as a lost cause.” If Javier were not granted asylum, he would be deported back to El Salvador, which he said was the equivalent 0f someone saying, “Give me five coffins, I’m sending this family to be buried there.”

“If I step on Honduran soil, they will kill us. And they will not care that I have a child.”

Jimena, 21-year-old woman, Honduras

Trying to Block Asylum Altogether: Third-Country Asylum Rule

Most asylum seekers waiting on the U.S.-Mexico border traveled through Guatemala and Mexico to reach a border crossing point. In what seems to be an effort to block asylum seekers from making a claim in the United States, in July 2019, the DHS and the Department of Justice issued the Third-Country Asylum Rule, also known as the “third-country transit bar.” This policy requires applicants to “apply for protection from persecution or torture where it was available in at least one third country outside the alien’s country of citizenship, nationality, or last lawful habitual residence through which he or she transited en route to the United States.”[85]

The Third-Country Asylum Rule practically bans all asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border for all nationalities, except Mexicans: Hondurans and Salvadorans would have to seek and be denied asylum in Guatemala or Mexico before they can apply in the United States. Guatemalans would have to apply and be denied in Mexico before they would be eligible for asylum in the United States. The same would apply to asylum seekers of other nationalities who travelled through these countries to reach the U.S-Mexico border.

The Third-Country Asylum Rule has been met with much resistance, given that it contravenes the longstanding asylum policies that allowed people to seek protection in the United States no matter how they arrived in the country. In July 2019, a California court issued a preliminary injunction against the rule. However, the following month, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit restricted the scope of this injunction to Ninth Circuit jurisdiction, which includes the border states of California and Arizona. This allowed the rule to be applied in the rest of the country, namely the border states of Texas and New Mexico, which are in the jurisdiction of other federal appeal courts.[86] On September 10, 2019, the Third-Country Asylum Rule was blocked again by a California district court, but this was reversed the following day by the Supreme Court. As of October 2019, this policy remains.

Although Guatemala is a gateway for Salvadorans and Hondurans trying to reach the United States’ southern border, the grim realities of its violent crime statistics underscore its likely unsuitability as even a temporary place of refuge for asylum seekers.[87] Guatemalans themselves, many of whom are fleeing violence linked to corruption, drug trafficking, and organized crime, filed almost 40,000 asylum applications in the United States in 2018.[88] PHR’s research shows how asylum seekers who sought to relocate to a third country, such as Mexico or Guatemala, continued to face threats or violence in those countries. For example, as detailed in previous parts of this report, Sergio (Case 15) and his family fled from Honduras to Guatemala. Sergio reported to PHR that, after two months in Guatemala, he was found by the same men he had been fleeing, so his family then went to Tijuana to seek protection in the United States. Similarly, as described in the previous section, David (Case 4) fled El Salvador to Mexico, only to be threatened again by violence there.

In addition to violence and impunity, asylum seekers in Mexico may face the risk of refoulement, given that Mexican officials have been known to return Central Americans to their countries of origin, despite migrants’ fears of persecution and/or torture if returned.[89] [90] As described earlier, Marta (Case 12) fled Nicaragua due to political persecution. She reported to PHR that, after two days on a bus, she and her son were stopped by Mexican immigration officials at the Mexico-Guatemala border. She pleaded not to be deported back to Nicaragua, stating that she would be killed, and asked to be taken to the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance, the government agency responsible for processing refugee claims. Both requests were ignored, and Marta and her son were deported back to Nicaragua, where they were almost sent to a prison where political prisoners are held. Given her previous experience in Mexico, Marta continues to live in fear: “I am afraid of everyone here. I feel that if I go to the corner, someone will come by and kidnap me, asking for a ransom.”

Conclusion

All asylum seekers included in this report sought protection due to targeted violence and intimidation from non-state actors, as well as violence by and/or denied protection by state authorities in Mexico and Central America. While they represent a small sample of the thousands of asylum seekers currently waiting their turn to seek protection in the United States, their cases indicate that they have strong grounds to seek asylum and that their claims should be heard in a prompt and fair manner.

While the Obama administration implemented concerning policies regarding detention and deportation, since 2016, the Trump administration has undermined the integrity of the U.S. asylum system, introducing a series of restrictive policies that defy both international and U.S. law and egregiously obstruct the right to seek asylum. These policies have placed people who are already in vulnerable situations – asylum seekers fleeing violence and trauma in their home countries[91] – at further risk. Physicians for Human Rights’ findings point to the urgent need to protect the right of individuals to seek asylum in accordance with federal and international laws by implementing the following recommendations.

Recommendations

To the U.S. Government:

- Ensure that the right to seek asylum is safeguarded, including when states are unwilling or unable to protect people from persecution by non-state actors, such as gang violence and domestic violence.

- End all practices that bar asylum seekers from adequate and effective physical and legal protection inside the United States, including the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) and “metering” policies.

- Prioritize resources to ensure that ports of entry across the U.S.-Mexico border can process and consider asylum claims in a fair and timely fashion.

- Integrate trauma-informed standards and practices that are culturally and linguistically sensitive into every stage of the asylum-seeking process, from Customs and Border Protection processing through final adjudication.

- Uphold current United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) standards for non-adversarial questioning to ensure fair processes and end any programs intended to authorize law enforcement officials other than trained USCIS asylum officers to conduct credible fear interviews (CFIs).

- Provide the USCIS with adequate resources, staff, training, and supervision to appropriately conduct CFIs.

- Limit detention of asylum seekers and increase access to and availability of community-based alternatives to detention to better facilitate access to essential services such as legal counsel and physical and mental health care.

- Abolish family detention and refer family units to case managers who can connect families with nonprofit resources and representation.

- Apply a presumption in favor of release on bond or parole for asylum seekers who have passed CFIs, which in turn can relieve detention centers and end “metering.”

- Refrain from criminalizing or creating arbitrary restrictions on individuals and organizations working to defend migrant rights on the U.S. or Mexican side of the border.

- Cease to use tariffs, trade sanctions, foreign aid, or other measures to pressure other countries to enter into “third country” agreements, especially if these countries are unable to provide effective legal or physical protection to asylum seekers.

- Immediately grant outstanding requests by the United Nations Special Procedures and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to visit the U.S.-Mexico border for independent reporting and monitoring of policies and practices that affect the internationally recognized right to seek asylum.

To the U.S. Congress:

- Exercise oversight of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Department of Justice, and the Department of Health and Human Services by holding oversight hearings, monitoring through congressional delegation visits, and requesting documentation from government officials involved in the asylum process.

- Direct DHS to immediately abolish the MPP and “metering,” as well as defund any policies that may negatively impact the right to seek asylum, such as pilot programs intended to authorize law enforcement officials other than trained USCIS asylum officers to conduct CFIs.

- Propose and pass new legislation to affirm the full range of rights guaranteed to asylum seekers to counteract any executive or departmental policies or directives that effectively restrict individuals’ access to asylum protection.

- Provide adequate funding to ensure USCIS has sufficient resources to appropriately conduct CFIs.

- Publicly support the work of individuals and organizations working to defend the rights of asylum seekers on the U.S. and Mexican side of the border and monitor any threats to their ability to carry out this work.

To UN Member States:

- Deliver statements under relevant items that address violations of international law pertaining to the situation of asylum seekers on the U.S.-Mexico Border.

- Pressure the United States, Mexico, and the pertinent Central American countries, such as El Salvador and Honduras, to accept visit requests from relevant Special Procedures, including the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants, Special Rapporteur on the right to health, Special Rapporteur on racism and xenophobia, and the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions.

- Issue a joint statement at the UN Human Rights Council reiterating the recommendations made to the U.S. government in this report, and on the rights of asylum seekers on the U.S. border, especially in relation to the UN Resolution on Migration A/HRC/41/L.7.

- Include recommendations about the situation of asylum seekers in the United States’ Universal Periodic Review in May 2020.

- Condemn any measures that criminalize or create arbitrary restrictions on individuals and organizations working to defend migrant rights and provide a safe and enabling environment for their work around the globe.

To the Governments of El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, and Nicaragua:

- Address the factors that drive asylum seekers toward the U.S. border, especially violence by state and non-state actors and endemic impunity for human rights violations.

- Monitor the cases of asylum seekers returned through the MPP and ensure that the principle of non-refoulement is respected, as well as provide adequate essential services while asylum seekers wait in Mexico, including access to physical and mental health services.

- Condemn the MPP and any other policy or measure that does not uphold the principle of non-refoulement, closely monitoring cases that DHS has publicly stated would be exempt from the MPP.

- Create mechanisms to identify any asylum seekers who could face risks if returned to their country of origin and provide them effective and immediate protection.

- Cease to militarize borders and preserve the right to freedom of movement by keeping borders open for those who wish to seek the right to asylum in another country.

- Provide a safe and enabling environment for individuals and organizations working to defend the rights of asylum seekers.

To the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights:

- Conduct a formal investigation along both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border to document actions and policies by Mexico, Central American countries, and the United States that negatively impact the human rights of migrants, particularly asylum-seeking Central Americans who transit through Mexico to reach the United States.

- Hold hearings before the Inter-American Commission aimed at exposing the root causes of mass migration from Central America to the United States and developing standards relating to the treatment of migrants, particularly in connection with policies such as “safe country” that negatively impact or in any way limit the right to seek asylum.

- Publicly support the work of individuals and organizations working to defend the rights of asylum seekers on the U.S. and Mexican side of the border, including civil society organizations, lawyers, and journalists, and monitor any threats to their ability to carry out this work.

Annex: Cases

Case 1 : Adriana, 16-year-old girl, El Salvador

Case 2: Josefina, 36-year-old woman, El Salvador

“He would always tell me that he would kill me if I did not go with him. He would not let me be with anyone else. (…) He told me that he would kill me and bury me.”

Adriana

When Adriana was 14 years old, she left home to live with her then boyfriend Pedro, a 16-year-old boy whose brother was a gang leader. After three months living together, he became increasingly controlling and restricted Adriana in every way. He would not let her wear makeup, see her family, speak to others over the phone or social media, or even go to school.

When they were in public, Pedro often would get angry if Adriana lifted her head to look above the ground, accusing her of flirting with others. He routinely sent her videos showing how gang members killed their girlfriends or forced them to dance naked on camera, explaining that this is what happened when women did not follow orders. He also described women being gang-raped or having objects like bags or bottles forced inside them.

Adriana turned for help to her mother, Josefina, who told Pedro that she was taking her daughter back because she was a minor and that she was prepared to involve the police. He replied, “You do not know what you are saying. It appears that you do not love your family because they will all be gone if you open your mouth,” implying that his brother’s gang would retaliate. On another occasion, Pedro warned the family that “blood would flow” if they tried to denounce the gang.

Adriana was responsible for all the domestic work for Pedro’s family, and rarely had food to eat. When she became pregnant at age 15, Pedro’s mother told her that she would take the child away soon after Adriana gave birth. As Adriana lost weight and became pale during her pregnancy, her family became increasingly worried. One day, Adriana’s grandmother asked her to meet her for lunch. Pedro spent most of his days out, so Adriana visited her grandmother. When she returned, Pedro met her on the street to tell her that he had not given her permission to go. He hit her and took her phone away so she could no longer communicate with her family.

One night when Adriana was 4-1/2 months pregnant, she asked Pedro what they were going to eat for dinner. He said he had no money, so she questioned how he could buy drugs: “How do you have an unending supply of marijuana while I go hungry?” When she threw away his stash of marijuana, Pedro beat her in the back and the stomach. Adriana woke up bleeding in the middle of the night, so she walked to her mother’s home alone for help. A neighbor then drove them to the hospital, where Adriana spent 20 days and eventually lost her pregnancy. That night, she found she had been pregnant with twins.

“They control everything and know where everyone is at all times. I had not told anyone where we were, but he knew where we were.”

Josefina

When they left the hospital, Adriana returned to her mother’s home without telling anyone, but Pedro found out and showed up the following day to take her back. Josefina protested, but he told her, “Do not get involved. I am not in a relationship with you. Since the first day, she knew that this would be forever.” Out of fear, Adriana went with Pedro.

Adriana had scheduled follow-up visits at the hospital and Pedro gave her permission to go only if she went with his mother. A month later, Josefina came up with a plan: when Pedro allowed Adriana to see her grandmother on her birthday, she and Josefina fled to another town. During their two months in hiding they received threats from gang members via social media and they feared for their grandmother’s life. A neighbor later told Josefina that the gang looted the family’s home and took all their belongings.

Eventually, Adriana and Josefina had to flee El Salvador entirely. In late October 2018, they joined the migrant caravan that traveled from Central America to Mexico. After spending two months working in Mexico City to pay for the rest of their journey, Adriana fell ill and had to spend time in another town receiving medical treatment. She and Josefina arrived in Tijuana in February 2019 to seek asylum in the United States. They blocked all communication with family and friends in El Salvador out of fear of being tracked by the gang.

PHR’s Clinical Evaluation

PHR’s clinical findings are highly consistent with Adriana’s narrative. Adriana is tearful during the interview. She reports feeling irritable, stressed, and easy to anger. She has nightmares about the videos Pedro showed her of women being abused, as well as difficult parts of the journey (such as crossing a river) to Tijuana. Adriana reports having difficulty sleeping and she startles easily. She avoids people or situations that remind her of the events that she experienced and tries to block memories of the events. She reported that when she recalls an incident, her heart races.

Like many survivors of domestic abuse, Adriana feels guilty and ashamed; she wonders if she did enough to stop the events or if she brought the events upon herself. However, Adriana is aware that she deserves to be in a safe environment, where she can grow as an adolescent. She is currently in the care of Josefina, who is a loving mother who cares for her. Despite the trauma that she has experienced, Adriana demonstrates resilience, likely because of this protective influence in her life.

Case 3: Benjamín, 18-year-old man, El Salvador

“I was very lucky because most young men are returned [to their families] dead in black bags. And even those are lucky because they often kill the family, too.”

Benjamín

As a teenager, Benjamín spent most of his time studying and playing soccer or basketball, but he was unable to finish high school. Benjamín’s then-stepfather was increasingly hostile as he became involved with arms and drug trafficking through local police officers. He often beat Benjamín’s mother and, when she ended the relationship with him, he threatened her – so she filed a complaint with the police. In retaliation, the stepfather destroyed the kitchen where Benjamín’s mother cooked to make a living. When she went back to the police, the officers claimed that they could not do anything because she still communicated with him. Benjamín believes his stepfather was protected by the police due to their mutual links to arms and drug trafficking.

With no options for protection, Benjamín and his family fled to another town, but this area was dominated by rival gangs and newcomers are often targeted as suspected informants. As Benjamín’s family began to receive threats in this new town, they returned to their hometown, in the hope that tensions with the stepfather had dissipated. However, the stepfather continued to harass the family and he sent Benjamín social media messages which ranged in tone from menacing to conciliatory, asking Benjamín to facilitate communication with his mother.

One afternoon, Benjamín’s stepfather sent him a message to step outside his house. As soon as he did, Benjamín saw three police officers wearing uniforms from El Salvador’s elite anti-gang unit. A friend of Benjamín was arriving at the same time and the officers forced them into a car. They drove for 30 minutes to a remote area, where the officers made the two men get out and kneel on gravel with their hands cuffed behind their backs. For two hours, the officers beat them with their shirts pulled over their faces, so they would have difficulty breathing. One officer forced Benjamín to hold a firearm, which he believes was to register his fingerprints on the weapon. The officer also made Benjamín bite a large rock, threatening to smash his face with it if he refused.

The police officers repeatedly tried to force Benjamín into falsely confessing his involvement with gangs, a common tactic by police forces under fire for ineffective crime-fighting. Benjamín’s friend pleaded with the officers to stop, saying this was a false accusation. In response, they beat the friend until his mouth was gushing blood and said they were going to kill them. They then drove them to a police station, where they were beaten for another three to four hours. Eventually, the officers slowed down the beatings, as they noticed Benjamín and his friend getting weaker.

Six police officers then drove the two young men back to Benjamín’s home. When they arrived, three of the men entered the house, allegedly searching for guns and drugs. Benjamín suspected that they were trying to plant drugs and guns to falsely incriminate him. While the other three officers guarded Benjamín and his friend in the car, the officers inside interrogated Benjamín’s mother for hours about his whereabouts, saying that he was suspected dead due to his alleged gang involvement. Eventually the police told her that her son was alive and returned him to her, but Benjamín’s friend remained in jail for three days.

Benjamín also spent three days in bed recovering from his wounds. He states that his mother understood what had happened, but they had an unspoken agreement not to discuss it in order to preserve their safety. Out of fear, Benjamín fled El Salvador. He waited three months at the Mexico-Guatemala border for a humanitarian visa to travel through Mexico legally. Even with this documentation, he faced extortion by local police officers, who often told him that his visa was not valid and that he was therefore in the country illegally.

“If I went back to El Salvador, I would not survive. I think it would be worse and they would finish me. I also fear for my family and my younger brother.”

Benjamín

PHR’s Clinical Evaluation

PHR’s clinical findings are highly consistent with Benjamín’s allegations of ill-treatment. Benjamín tells his story with a clear, steady voice in a linear manner. As expected, he is uncomfortable when discussing the more violent moments and exhibits signs and symptoms suggestive of both post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder. Moreover, he screened positive for both depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.