Executive Summary

Physical and psychological abuse and inadequate medical care have long been documented in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facilities, where previous infectious disease outbreaks were poorly contained. In 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the United States, it became clear that ICE’s continued negligence, coupled with the vast expansion of U.S. immigration detention, would likely lead to a public health disaster.

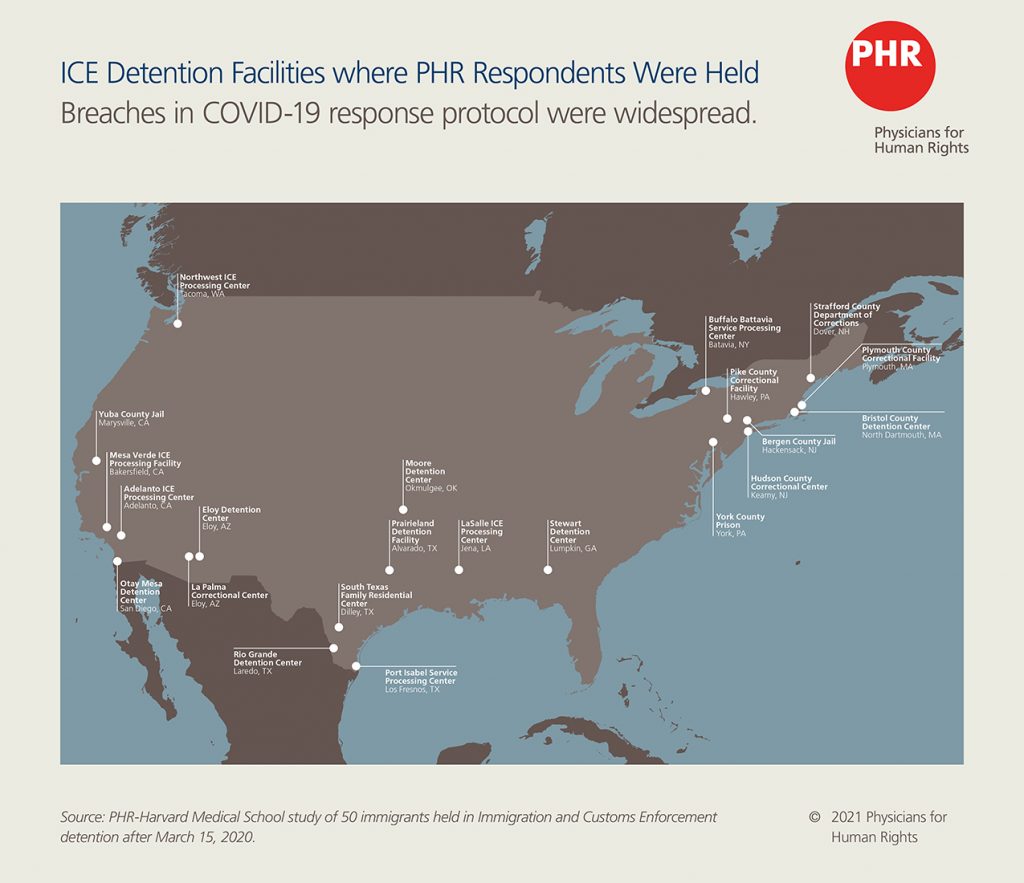

Given the lack of transparent data and the severe health risks in congregate settings caused by the pandemic, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) staff and Harvard Medical School faculty and students sought to document conditions experienced by people recently released from U.S. immigration detention. From July 13 to October 3, 2020, the research team conducted 50 interviews of immigrants formerly detained by ICE using a standardized questionnaire covering 1) Demographics; 2) COVID-19 education; 3) Hygiene and sanitation measures; 4) COVID-19 testing and medical management; and 5) Protests and retaliation. The 50 participants were detained at 22 different ICE detention facilities – representing nine county facilities and 13 private facilities – in 12 different states. Overall, 52 percent of interviewees reported at least one comorbidity that placed them at an absolute high risk of severe COVID-19 if they contracted the virus. All study participants were 18 years of age or older, in the United States at the time of the interview, and had been held in ICE detention with a release date on or after March 15, 2020.

ICE practices did not comply with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance … creating unacceptable health risks which violated the constitutional and human rights of detainees.

Information reported by the interviewees uncovered significant shortcomings in ICE’s response to the virus. Staff efforts to inform people about COVID-19 were limited and inconsistent. The vast majority of respondents (85 percent) first heard about COVID-19 in detention by watching the news on television, while ICE staff in some facilities attempted to downplay the significance of COVID-19 and actively prevented people from learning about the virus from the news by asking them to change the television channel.

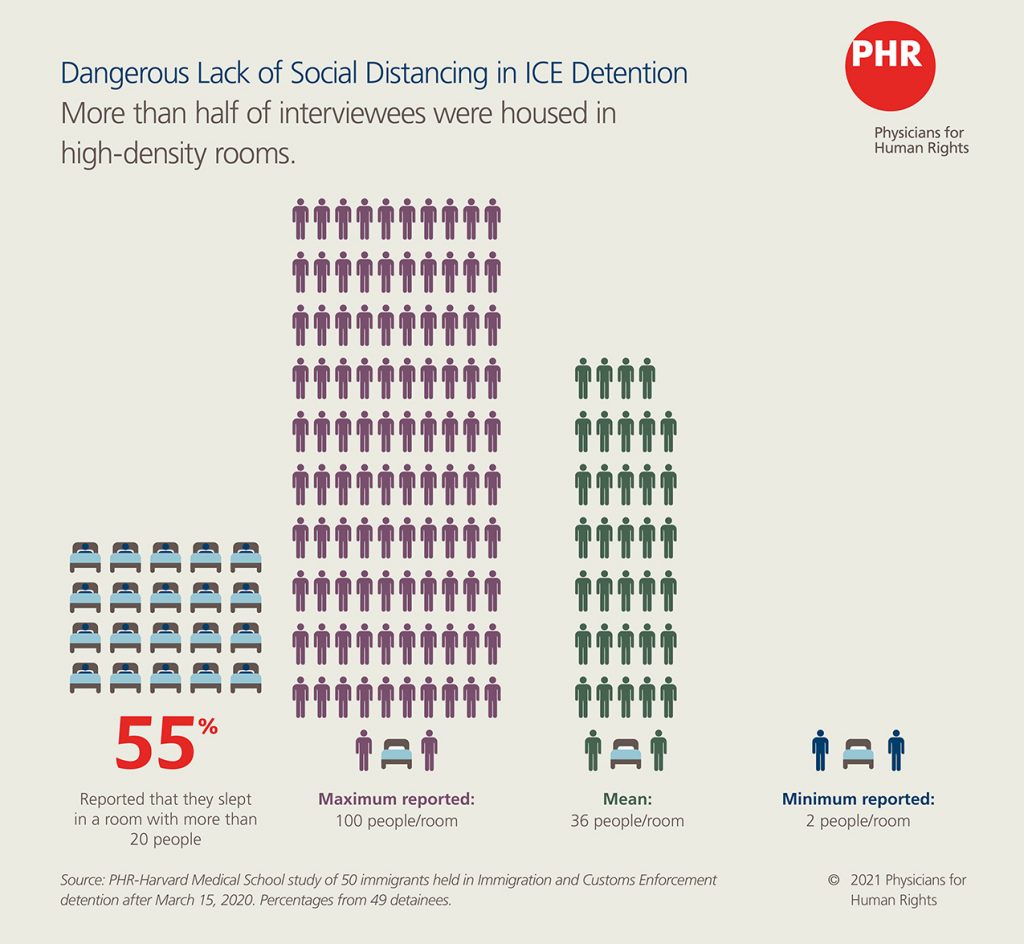

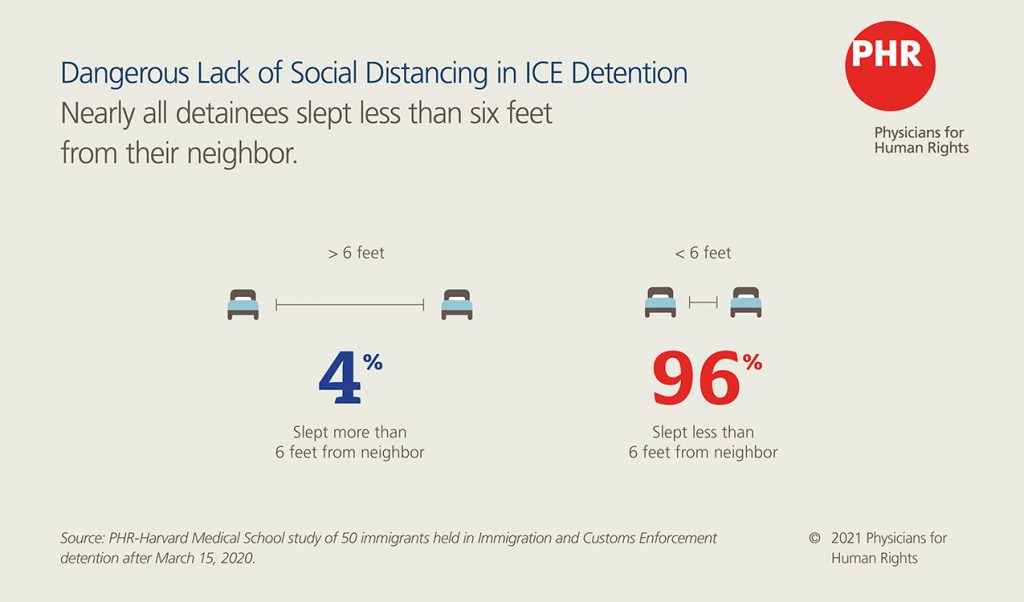

Nearly all immigrants interviewed were unable to maintain social distance throughout the detention center. Eighty percent reported never being able to maintain a six-foot distance from others in their eating area. Some 96 percent reported that they were less than six feet from their nearest neighbor when sleeping. The average distance reported between beds was 2.87 feet. Twenty-seven people reported that when new individuals entered the detention center after March 15, they were not quarantined for two weeks before entering the general unit.

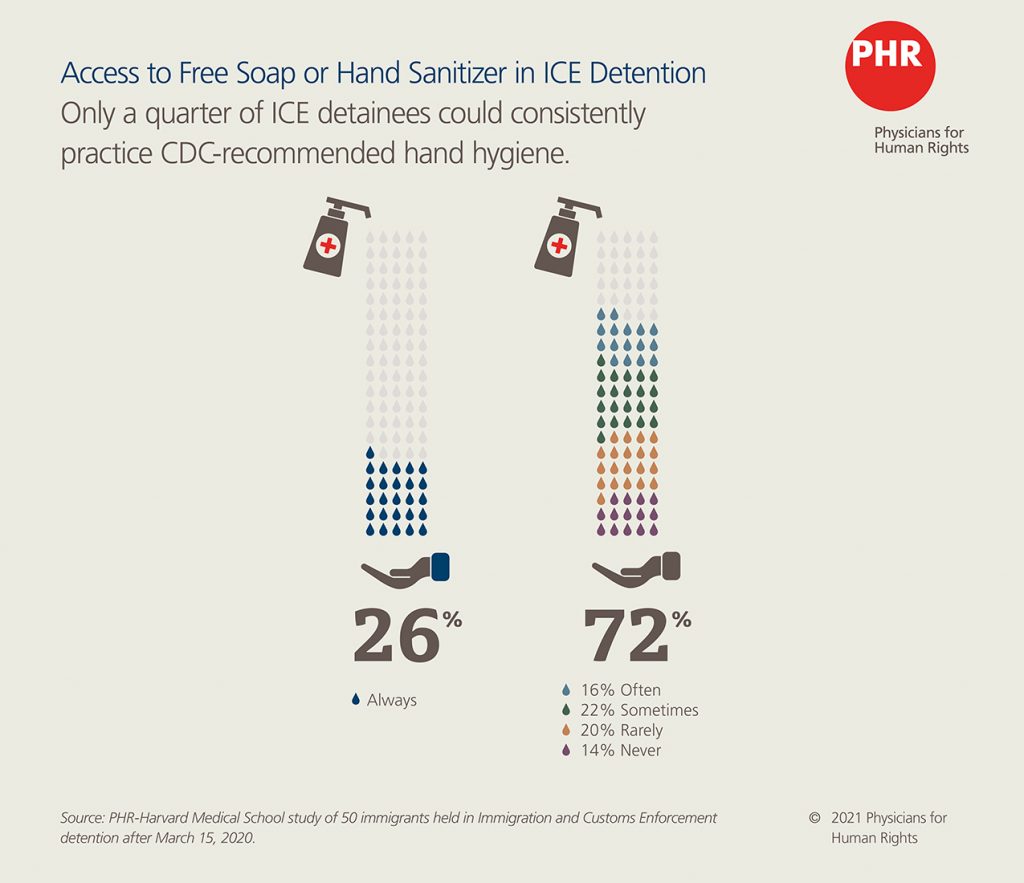

Forty-two percent of participants reported not having access to soap at some point during their detention. When soap or hand sanitizer was not available, some participants reported resorting to using shampoo to wash their hands, and one even used toothpaste. Thirty-six percent of participants reported relying on purchasing soap from the commissary. Several people relied on donations from outside organizations, while others had to forgo other basic necessities to purchase soap. Eighteen percent of participants reported most commonly using water alone to wash their hands. Eighty-two percent of people reported not having access to hand sanitizer anywhere in the detention facility. Twenty-six percent of participants reported never observing disinfection of frequently touched surfaces in common areas (e.g. doorknobs, light switches, countertops, recreation equipment). The overwhelming majority (83 percent) reported that detainees disinfected the common areas themselves.

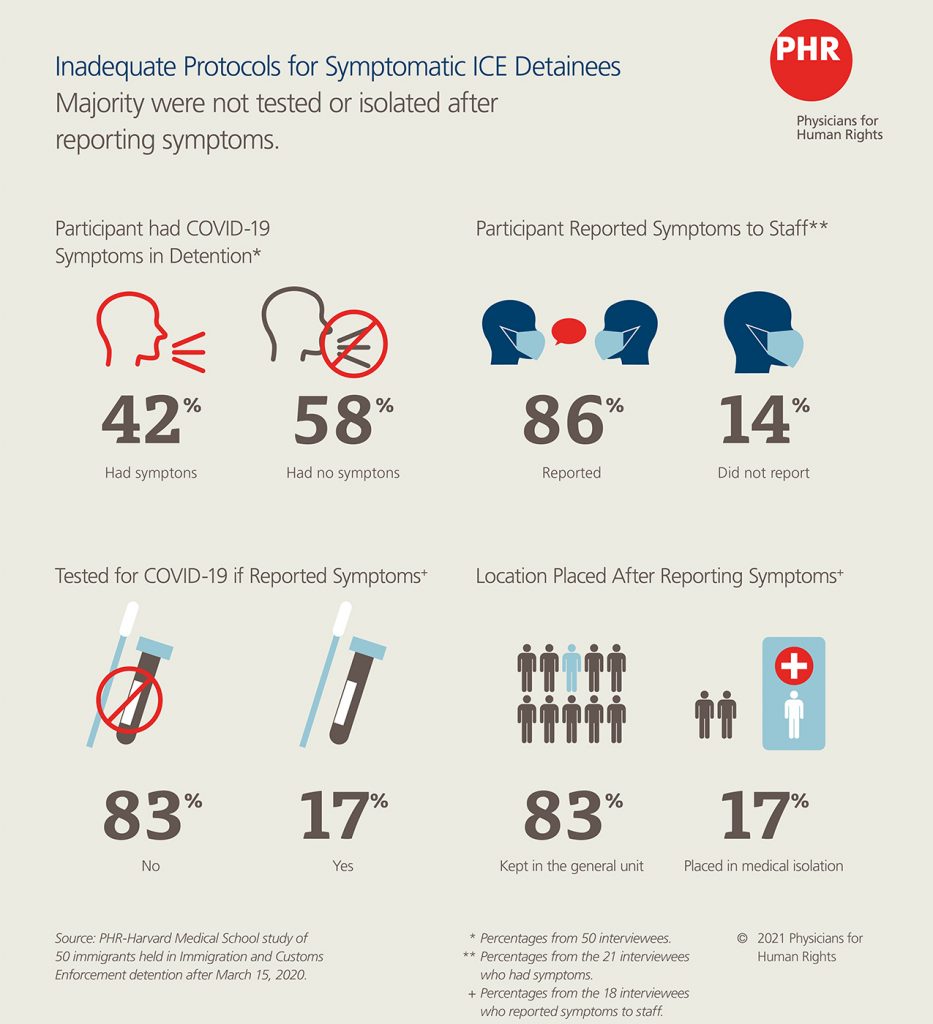

Twenty-one out of 50 people interviewed (42 percent) experienced symptoms of COVID-19 during the pandemic, such as fever, cough, muscle aches, and loss of smell. Three out of these 21 (14 percent) never officially reported their symptoms due to fear of being sent to solitary confinement or other punishment, or anticipation of denial of medical care. Out of all respondents who reported symptoms, only 17 percent (three people) were appropriately isolated from the general population and tested for COVID-19, one of whom tested positive. The remaining 83 percent (15 people) reported their symptoms to facility staff members but did not get tested for COVID-19 and were not isolated.

Interviewees reported facing prolonged wait times before being able to see a medical professional, with an average wait time of 100 hours (approximately four days). One person reported having had to wait a total of 25 days for an appointment. Importantly, two people were never seen by a medical professional at all, even after reporting their symptoms to staff members.

While 88 percent of all participants (44 people) had at least one comorbidity placing them at possible increased risk of severe COVID-19, 56 percent (28 people) reported these risk factors to detention staff, but only four of them were told that they were at high risk of having a serious illness with COVID-19. None of those four were given the option to have an individual room.

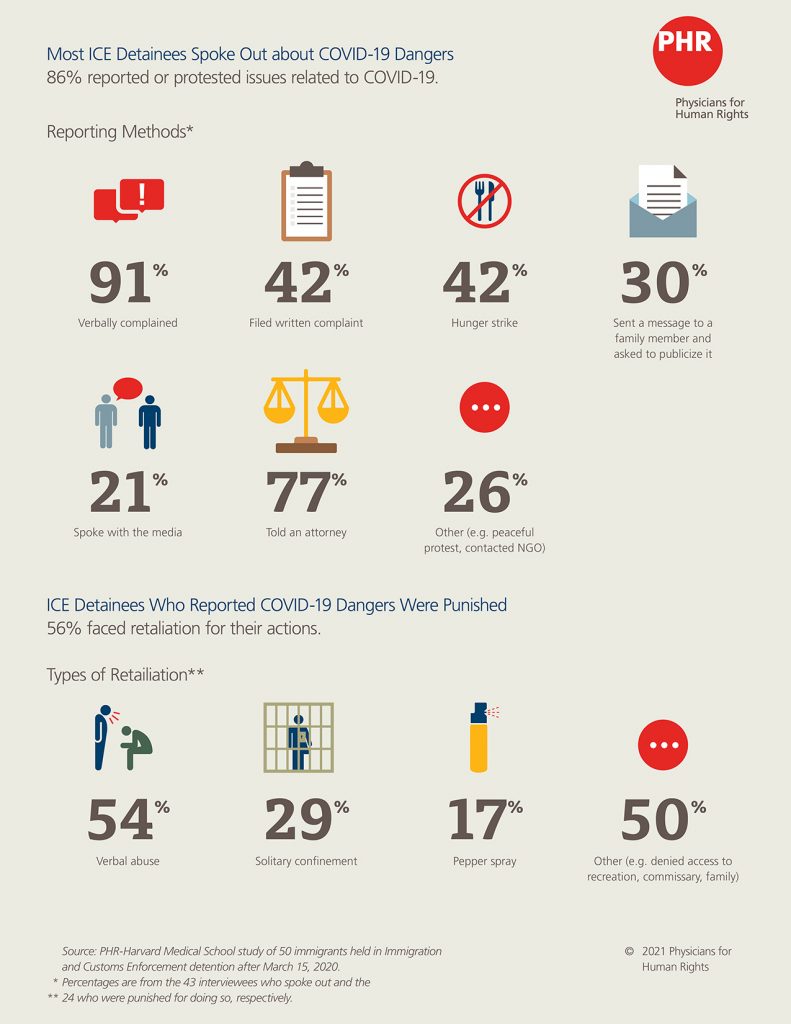

Forty-three study participants (86 percent) stated that they reported and/or protested about issues related to COVID-19, including verbally complaining to staff about unsanitary conditions or lack of personal protective equipment, filing formal grievances, going on hunger strikes, reporting conditions to lawyers, reporting conditions to the media, and sending messages to family members with the hope they would be publicized. Of these 43 who protested, 56 percent (24 people) reported experiencing acts of intimidation and retaliation after their complaints, including verbal abuse by detention facility staff, being pepper sprayed, being placed in solitary confinement, and experiencing threats or actions of limiting food, communication, or commissary access.

The government cannot put people in danger or act with deliberate indifference to a foreseeable or obvious threat, and is required to provide for the reasonable health and safety of people in detention.

As civil detainees, people in immigration detention are entitled to due process under the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and cannot be held in punitive conditions. The government cannot put people in danger or act with deliberate indifference to a foreseeable or obvious threat, and is required to provide for the reasonable health and safety of people in detention. The UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, which apply in all detention settings, confirm that health care for people who are detained is the responsibility of the state, and that health care also must follow public health principles in regard to management of infectious disease, including treatment and clinical isolation.

In fact, international law limits the use of immigration detention and prohibits criminalizing border crossing for asylum seekers. Article 31(2) of the UN Refugee Convention permits states to restrict refugee freedom of movement only when necessary, otherwise it may amount to a “penalty,” which is prohibited under the Convention. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees’ (UNHCR) Executive Committee considers detention of asylum seekers as meeting the necessity test only when the government detains people to verify their identity or issue documents, to make a preliminary assessment of their asylum claim, or based on an individualized security assessment. International standards consider immigration detention as a last resort and require periodic hearings for all types of detention in order to prevent arbitrary detention.

International bodies and U.S. federal courts have applied these standards to the context of the pandemic. The World Health Organization, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, and UNHCR stated in March 2020 that, given the risk of severe illness and death from COVID-19, people in immigration detention should be released “without delay.” U.S. federal courts have variously ordered ICE to locate and release people at high risk of severe illness or death due to the coronavirus, to give masks and sanitizer to detainees, to ensure availability of testing, and to take a range of precautionary measures, such as isolating people who test positive, temporarily halting intake, enforcing social distancing and mask wearing, and providing appropriate sanitary and hygiene supplies.

The harsh and punitive conditions reported in this study show that ICE practices did not comply with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance or with ICE’s own Pandemic Response Requirements, creating unacceptable health risks which violated the constitutional and human rights of detainees. International law requires governments to use immigration detention only as a last resort, and the U.S. constitution prohibits punitive conditions in civil detention, requiring the government to ensure safe and healthy conditions. As an urgent matter, the U.S. government should release all people from immigration detention to allow them to safely shelter in the community, absent a substantiated individual determination that the person represents a public security risk. Safely releasing people from immigration detention is in accordance with international human rights and U.S. constitutional standards and represents the best way to prevent further outbreaks of COVID-19.

-

0

People held in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Detention, as of January 4, 2021.

Introduction

In April 2020, the United States held more than 56,000 people in 220 immigration detention facilities across the country in what has become the largest immigration detention system in the world[1] – a far cry from the 7,475 people who were held in U.S. immigration detention in 1995.[2] Xenophobia and discrimination against Black and brown immigrants have been driving factors in the increase in the immigration detention population, a manifestation of the systemic racism that has also driven mass incarceration in the United States.[3] Expansion of immigration detention accelerated under the presidency of Donald Trump, whose administration opened numerous government-run detention centers and increased the number of contracts with private for-profit companies to operate additional facilities.[4] Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the federal agency that runs these facilities, has long been accused of human rights violations, physical and psychological abuse, inadequate medical care leading to otherwise preventable health crises, and deaths in custody. Additionally, previous badly contained infectious disease outbreaks all point to “systemic failures of healthcare provision and government oversight.”[5],[6] In fact, independent medical review of detainee death reports concluded that in 8 out of 15 reported deaths in ICE custody between December 2015 and April 2017, medical negligence was a contributing factor.[7] In 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the country, it became clear that ICE’s continued negligence, coupled with the vast expansion of immigration detention, would likely lead to a public health disaster.[8]

Immigration detention facilities are not unlike other congregate settings, such as nursing homes and prisons, where the infection rate of the novel coronavirus virus, SARS-Cov-2, and death toll from COVID-19 are disproportionately high.[9] Despite the risk and calls for decarceration,[10] ICE has been largely unwilling to release immigrants into the community in the United States except under the pressure of litigation, instead stating that it has followed U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines to manage the pandemic in detention centers.[11] However, so far, ICE’s handling of COVID-19 has resulted in, at minimum, reported infections of 558 people currently held at these facilities and eight deaths in custody – numbers considered to be undercounted.[12]

Motivated by the lack of transparency about the COVID-19 public health disaster in immigration detention, this study seeks to shed light on the experiences of immigrants who survived the pandemic in detention. Through the stories of 50 individuals, we aim to provide a snapshot of the conditions in some detention facilities, and to make recommendations for next steps to reduce the risk and harm from SARS-CoV-2 in immigration detention.

Background

The number of people per month who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19) in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention between April and August 2020 was between 5.7 to 21.8 times higher than the case rate of the U.S. general population during that same time.[13] While testing rates increased during that time, so did test positivity rates, demonstrating that increased case rates could not be exclusively attributed to increased testing and suggesting that strategies to prevent infection have largely failed.[14] At the time of this report’s drafting, the number of cumulative infections ICE reports sits at 8545,[15] despite the fact that the number of people held in detention has decreased[16] and now stands at 16,037.

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the country, it became clear that ICE’s continued negligence, coupled with the vast expansion of immigration detention, would likely lead to a public health disaster.

ICE has internal agency guidelines, which could have addressed these challenges from the very start of the pandemic. On March 15, 2020, ICE reported that it was “incorporating CDC’s [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] COVID-19 guidance” into its own existing protocol,[17] the Pandemic Workforce Protection Plan, which was activated to address coronavirus as early as January 2020.[18] Also in January 2020, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issued guidance which included the use of personal protective equipment (PPE). By April 10, 2020, ICE published its first version of the “Enforcement and Removal Operations COVID-19 Pandemic Response Requirements” (PRR). Around this time, public health experts were calling for the widespread release of people from immigration detention as the only way to ensure safety.[19] New versions of the PRR were released on June 22, July 28, September 4, and October 27, and all versions utilized guidance from the CDC.[20] ICE’s updated PRR, issued on October 27, contains positive changes such requiring facilities to identify those with medical vulnerabilities, testing new arrivals, and clarifying that medical isolation is not solitary confinement; however, standards alone do not guarantee proper implementation.[21]

Historically, ICE has failed to meet its own health and safety standards. In 2019, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) of the DHS found “egregious violations” of ICE’s own 2011 Performance-Based National Detention Standards.[22] Violations included multiple issues related to health and safety, such as a lack of hygiene supplies, unsafe food, and unclean bathrooms.[23] In 2016, the OIG also found major gaps in DHS’s ability to respond to a pandemic.[24]

ICE’s adherence to its own COVID-19 standards has been equally poor to date. For instance, CDC guidelines on proper “cohorting” include “isolating multiple laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases together as a group”; such “cohorting” should only occur “if there are no other available options.”[25] However, in April, immigrants at La Palma Correctional Center in Arizona were being cohorted in their respective housing units.[26] Grouping together those who have COVID-19 with those who may not is a recipe for accelerated transmission, and risks deadly consequences.

Though the PRR recommends that facilities provide adequate hygiene supplies and educate people about the virus, individuals in immigration detention have spoken out about a lack of hand sanitizer, soap, and masks, and non-existent educational materials about the virus.[27] Human rights advocates have also reported inappropriate and dangerous use of disinfecting chemicals to sanitize ICE detention facilities; for example, people in detention reported burning, bleeding, and rashes in response to the use of HDQ Neutral, which is an industrial-strength chemical.[28]

Additionally, the standards themselves contains significant caveats which limit their effectiveness in preventing the spread of COVID-19, while problematically and inappropriately limiting ICE’s responsibility to uphold these measures. For instance, while the PRR states that “Whenever possible, all staff and detainees should maintain a distance of six feet from one another,” it also notes that “strict social distancing may not be possible” and immigrants are recommended to “sleep head to foot.”[29] At times, concrete guidelines have not been in keeping with public health principles; for example, advocates have noted that ICE did not recommend testing people who were asymptomatic, though the CDC had already warned that the virus could be spread through asymptomatic carriers.[30] Instead, the PRR required facilities to screen people entering detention centers based on their own verbal expression of a very limited number of symptoms of COVID-19 (when it was already known that the list of potential COVID-19-related symptoms was more extensive), rather than an actual negative test result.[31]

Lastly, the PRR includes clawback clauses which allow for significant exceptions. For instance, the July 28 PRR states that facilities should, “where possible, limit transfers of detained non-ICE populations to and from other jurisdictions and facilities unless necessary for medical evaluation, medical isolation/quarantine, clinical care, extenuating security concerns, to facilitate release or removal, or to prevent overcrowding.”[32] These guidelines do not apply to the many detained immigrants who are not held by ICE, nor do they account for the many exceptions to the rule.[33] In practice, ICE has continued transfers which likely contributed to spread of the virus. For example, in May, an ICE attorney admitted that ICE was not always testing people before transferring them, citing low testing capacity; when a federal judge in Miami ordered ICE to reduce occupancy of South Florida detention centers to 75 percent of capacity, ICE transferred people instead of releasing them.[34] Similar actions have been taken by ICE across the country.

ICE has undertaken a host of other harmful practices during the pandemic, such as: prolonged solitary confinement under the guise of medical isolation[35]; deportation of people from detention center COVID-19 hotspots to countries where these deportation flights contributed to the rise of COVID-19;[36] using tear gas,[37] commissary account freezing, and transfers as retaliatory measures against immigrants protesting their confinement during the pandemic;[38] and using the virus as a pretext to issue a series of executive actions aimed at closing the border based entirely on specious public health grounds generally contested by public health experts.[39]

There has been an overall reduction in the detention population due to expulsions, border closures, and deportation.[40] However, except for a brief pause in March 2020, ICE has also continued large-scale arrests of immigrants, including people with no criminal record, continuing intake of new people into detention during the pandemic.[41]

Despite ample public health and medical research recommendations for release … ICE states that it continues to hold more than 16,000 people in detention facilities across the country.

One of the most serious issues with ICE’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic is the lack of transparency. A whistleblower, who worked as a nurse in an ICE facility in Georgia, reported that she was demoted in retaliation for speaking up about insufficient COVID-19 precautionary measures in the facility.[42] The June 2020 report by the DHS OIG on ICE’s early pandemic response contained significant shortcomings, such as failing to include data on contracted staff or asking individuals in detention to provide feedback.[43]

When cases began to rise at the beginning of the pandemic, thousands of medical professionals wrote a letter to ICE recommending that the agency release people to community-based alternatives to detention while their cases were pending.[44] ICE ignored this letter. Yet, despite ICE’s objections, federal data has shown that the majority of people who are released from detention show up for their hearings,[45] and most immigrants have family or community connections with whom to reside.[46] Public health advocates’ guidelines describe how to conduct release in a safe way during the pandemic.[47]

Despite ample public health and medical research recommendations for release, and emergency litigation at the national, state, and individual level, as of January 2021, ICE states that it continues to hold more than 16,000 people in detention facilities across the country.[48]

Given the lack of transparent data and the severe health risks in congregate settings caused by the pandemic, PHR and Harvard Medical School faculty and students sought to document conditions experienced by people recently released from immigration detention. These interviews uncovered significant failures in the agency’s handling of the virus within its detention facilities, creating dangerous conditions and leaving immigrants with no recourse to protect themselves.

Methods and Limitations

From July 13 to October 3, 2020, the research team conducted 50 interviews of immigrants formerly detained by Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) using a standardized questionnaire. All study participants were 18 years of age or older, in the United States at the time of the interview, and had been held in ICE detention with a release date on or after March 15, 2020 (two days after the declaration of a national emergency due to COVID-19).[49] All interviews were conducted by WhatsApp call or standard telephone call, directly in the participants’ native languages (English or Spanish), or with an interpreter if needed (n=4). Interviews lasted one to two hours. Participation was voluntary, and all participants provided verbal informed consent to participate in the study. A $40 electronic gift card was offered to participants as reimbursement of a standard meal and phone minutes. This study was reviewed by the Harvard Medical School Institutional Review Board and determined to be exempt from further review. The study was also reviewed and approved by the Physicians for Human Rights’ Ethical Review Board.

Structured interviews included a questionnaire that was designed to assess the implementation of ICE’s National Detention Standards (NDS) (Version 2.0, 2019) as well as ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations COVID-19 Pandemic Response Requirements (PRR) (Version 1.0, April 10, 2020).[50],[51] Many of the questions were written to assess adherence to policies enumerated in the PRR, as well as the NDS, which were in place prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The questionnaire included five sections: 1) Demographics; 2) COVID-19 Education; 3) Hygiene and Sanitation Measures; 4) COVID-19 Testing and Medical Management; and 5) Protests and Retaliation. The data collected during the interviews were both quantitative and qualitative in nature. All quantitative data was statistically analyzed in Excel (Version 16.40).

Participant Recruitment

Participants were recruited through outreach to immigration attorneys. Attorneys were asked to present information about the study to clients who had been released from ICE detention on or after March 15, 2020, using a standardized script and flyer. By March 15, COVID-19 was known to be a serious infectious disease, especially in congregate settings; in that week there occurred the first report of an ICE staff member being infected. Both human rights groups and DHS medical expert whistleblowers issued warnings about the dire consequences of not releasing people from immigration detention.[52]

Attorneys were notified that this study did not include a language restriction. If individuals stated that they were interested in participating, they were referred to the study through their attorneys, who shared the participant’s phone number, time availability, preferred language, and preferred mode of contact (WhatsApp or phone). Attorneys did not share the names of participants with the research team in order to ensure anonymity and protect participants. Fifty-nine people were referred to the study and contacted by research staff. Nine of those decided not to participate in the study. Fifty people participated in the study and completed the entire questionnaire verbally. Forty-nine participants accepted the electronic gift card.

Human Subjects Protections

Referred participants were largely contacted through WhatsApp, which provides end-to-end encryption. For participants who did not have or prefer WhatsApp, a regular phone line was used to conduct the interview. Consent forms were shared with participants prior to the interview in their preferred language (either through WhatsApp message or text message services). Prior to initiating the interview, the consent form was verbally reviewed with participants in its entirety, and verbal consent was obtained. Participants were assured that their interview was confidential and anonymous, and that none of their responses would be communicated to their lawyer or affect their pending immigration case. During the interview, quantitative and qualitative data was collected in real time in a secure REDCap database. No identifying information was collected or stored. Participant information (including name of the referring lawyer and participant phone number) were collected in a separate REDCap database that cannot be linked to participants’ survey responses. Finally, participants who accepted the electronic gift card for participation were sent the electronic gift card through WhatsApp message, short message services, or, if preferred, email. Any email communication with lawyers and participants was conducted through a Harvard Medical School delegated access email account used exclusively by study staff, and all correspondence was deleted 30 days after completion of the study. The study staff’s WhatsApp accounts used to contact participants and conduct the interviews were cleared of correspondence data after completion of all interviews.

PHR shared the findings of this report with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and requested a response but had not received any as of the date of publication.

Limitations

The data presented in the report represent the experiences of 50 individuals held in ICE detention in a limited number of facilities across the United States. Our sample, therefore, may not be representative of the experiences of people held in ICE facilities after March 15, 2020.[53] Another limitation of the study is sampling bias – only people released from detention and still residing in the United States were interviewed, although many people in ICE detention during the pandemic have been deported and many continue to be detained. Additional sampling bias exists in this data, as most interviewees stayed in adult facilities and only one stayed in a family detention facility, therefore not representing the different types of facilities that ICE operates. Additionally, all interviewed detainees had representation from lawyers who in turn decided which clients to refer, reflecting possible selection bias on the part of our collaborating attorneys. Although this study did not include a language restriction, lawyers may have been more likely to refer clients with whom they could communicate more easily without the use of an interpreter. This data also includes recall bias, as responses are based on participant memory of detention conditions. There was additionally potential for variation between interviewers, but care was taken to minimize this variability through extensive interviewer training before and during the study period. The use of a structured questionnaire with consistent wording was designed to reduce interviewer bias. Lastly, the data captures experiences through August 2020 and is therefore a snapshot that will not include additional information that may be shaped by the coronavirus surge in the fall of 2020 with its further strain on resources and capacity.

PHR shared the findings of this report with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and requested a response but had not received any as of the date of publication.

Key Findings

Demographics

Of the 50 participants interviewed, 76 percent identified as male (n=38) and 24 percent as female (n=12). The age range was 20-52 years old (average age: 36 years old), with 46 percent of participants being in their 30s. The participants were originally from 22 different countries (nine from Mexico, eight from Venezuela, four from El Salvador, three from Cuba, and three from Uganda). With respect to languages, participants’ primary languages included English, French, Haitian Creole, Kinyarwanda, Luganda, Russian, Sonikeh, Spanish, Tigrinya, Twi, and Zulu. Many spoke two languages well, one of which was English or Spanish. Twenty-six interviews were conducted in English (52 percent), 20 in Spanish by native Spanish-speaking interviewers (40 percent), and four with a translator (two Spanish, one Russian, one Tigrinya) (eight percent).

Participants had entered the United States as early as 1980 and as recently as March 2020. With respect to their most recent detention, the average length of stay was 241 days (range: 14 days to two years). The 50 participants were detained at 22 different ICE detention facilities – representing nine county facilities and 13 private facilities – in 12 different states. Approximately the same number of people were held in county facilities as in privately contracted facilities. The private facilities were run by GEO Group (five facilities), CoreCivic (five), Ahtna Support and Training Services (one), Akima Global Services (one), and LaSalle Corrections (one). One participant was transferred between two facilities after March 15, 2020, another was transferred between three facilities after March 15, 2020. All were held in adult facilities, except for one person who was held in South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas. Participants were released from detention between March 16 and August 12, 2020, with six released in March, 20 in April, eight in May, 12 in June, three in July, and one in August.

“They didn’t want to talk about it. They were hiding information about the coronavirus from us. They didn’t tell us anything.”

37-year-old man, Plymouth County Correctional Facility

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lists certain conditions as putting individuals at high risk of severe illness from COVID-19, while other conditions might place an individual at increased risk.[54] Notably, these lists have been modified as more data has come out about high-risk comorbidities. In our study population, no participants were over 65 years old. Participants did, however, have several other comorbidities that are listed as either possibly or definitively placing them at high risk of severe illness, per the CDC. With respect to comorbidities listed as an absolute high risk, participants reported having a heart condition (20 percent), immunocompromised state (eight percent), adult-onset diabetes (12 percent), chronic kidney disease (four percent), and obesity or severe obesity (32 percent). Participants also reported having several comorbidities that the CDC lists as possibly putting them at increased risk for severe COVID-19: hypertension (30 percent), chronic lung disease or asthma (30 percent), liver disease (12 percent), and being overweight (38 percent).

Overall, 26 people (52 percent) reported at least one comorbidity that placed them at an absolute high risk of severe COVID-19 if they contracted the virus. When considering all of the comorbidities listed by the CDC as possibly or definitively conferring high risk of severe COVID-19, 44 people (88 percent) reported at least one such comorbidity.

Detention Staff Made Limited Efforts to Inform Detainees About COVID-19

Staff efforts to inform people about COVID-19 were limited and inconsistent, despite requirements to educate detainees as part of the PRR. Of study participants who were in detention after the implementation of the Pandemic Response Requirements (PRR) (41 people),[55] only five percent reported first hearing about COVID-19 from facility staff. The vast majority (85 percent) first heard about COVID-19 in detention by watching the news on television. ICE staff in some facilities even attempted to downplay the significance of COVID-19 and actively prevented people from learning about the virus from the news by asking them to change the television channel.

Early in the course of the pandemic, many people began looking for information on how to protect themselves from contracting COVID-19 in detention centers. While the majority of the 41 interviewees in detention after April 10 (66 percent) saw signs in the facilities about hand hygiene, only 39 percent saw signs about proper coughing etiquette. If any signs were posted, there were on average six signs throughout the entire facility. However, the presence of signs did not mean that immigrants could read or understand them, as the wording was sometimes only in English. Of people who reported seeing signs in facilities, 85 percent reported that signs were also available in Spanish and 11 percent reported that signs were available in another additional language. These trends suggest that ICE did not fully comply with the COVID-19 PRR that requires signage on hand hygiene and coughing etiquette to be offered in English, Spanish, and “any other common languages for the population inside each detention center.”[56] Considering the diverse languages spoken in each detention center, these signs were insufficient methods of education given the inconsistency of implementation and lack of language concordance.

ICE staff made few efforts to educate people directly, such as through verbal communication and educational meetings. Aside from signs, 39 percent of individuals reported learning about hand hygiene and 24 percent reported learning about coughing etiquette from staff directly. ICE staff also provided minimal guidelines and education around social distancing: a minority of immigrants reported being told by staff not to share eating utensils (22 percent), not to shake hands with others (37 percent), to stay six feet away from others (59 percent), and to avoid gathering in groups (34 percent). Per the COVID-19 PRR, ICE staff are required to educate detainees about these types of contact to minimize COVID-19 spread,[57] but many people were completely unaware of these policies.

Education from ICE staff about COVID-19 symptoms was also lacking. Only 46 percent (19) of respondents reported that ICE staff educated them directly about COVID-19 symptoms. Of the 19 people who received information about COVID-19 symptoms from staff, 100 percent were told that COVID-19 can present with fever, 68 percent were told about cough, and 63 percent were told about shortness of breath. This represents only three of more than 10 symptoms that can be suggestive of COVID-19. The lack of basic education on COVID-19 symptoms demonstrated that COVID-19 information, even when delivered, was minimal. Many detainees learned only by watching the news about COVID-19 spread and mitigation. Overall, interviewees reported that the lack of comprehensive information contributed to high levels of fear and anxiety among detained immigrants about the severity of the disease and their safety in detention.

Social Distancing Did Not Exist in Detention

Nearly all immigrants interviewed were unable to maintain social distance throughout the detention center. Eighty percent reported never being able to maintain a six-foot distance from others in their eating area. Respondents emphasized that even when they were told to stay six feet apart, it was nearly impossible to do so: “In dormitories, even staying apart three feet is impossible, there’s no way they can say that. How could you tell people to stay six feet apart?” (29-year-old man, Yuba County Jail). One person reported, “When the 80 of us ate together, we were elbow-to-elbow” (27-year-old man, Tacoma Northwest Detention Center).

Interviewees slept in rooms that on average housed 36 people (Range 2-100, Median = 34). Some 96 percent reported that they were less than six feet from their nearest neighbor when sleeping. The average distance reported between beds was 2.87 feet. Some 32 percent of interviewees were told to sleep “head-to-foot” with their nearby neighbors. One person reported: “They told us to sleep head-to-foot after they started getting lawsuits” (51-year-old man, Yuba County Jail). Many reported that sleeping head to foot “didn’t make a difference because our beds were four feet apart.” (32-year-old man, Yuba County Jail).

“On the bunk beds, you could feel the other person’s breath on you, it was too close.”

29-year-old man, Yuba County Jail

ICE acknowledges that strict social distancing may not be possible in detention facilities but still requires facilities to implement several measures to facilitate social distancing, including: avoiding congregating in groups of 10 or more, maintaining a distance of six feet as much as possible, rearranging beds to allow for six feet between people when sleeping, recommending that people sharing sleeping quarters sleep “head-to-foot,” and staggering different housing units’ meal and recreation hours.[58] Despite these guidelines, the interviews indicate that after the PRR was published, because of detention center organization, none of these measures were consistently implemented. As of March 1, 2020, the CDC recommended that people maintain physical distances from one another of at least six feet, especially in congregate settings.[59] Interviews demonstrate that ICE was also not adhering to these guidelines prior to the PRR.

The PRR outlines that facilities should reduce their populations so they can transition people from dormitory-style housing to “hous[ing] detainees in individual rooms.” However, few detention centers implemented changes to their housing practices. Only six people (13 percent) reported that there was a change in their housing after March 15, 2020. In these new housing arrangements, individuals slept in rooms that housed 10 people on average (Range 2-40, Median = 2). However, these changes in housing sometimes came with additional sanitation problems. Two interviewees shared that their new housing had major sanitation and plumbing problems, as the sink and toilet in the cells were not functional.

“When the 80 of us ate together, we were elbow-to-elbow.”

27-year-old man, Tacoma Northwest Detention Center

Another major concern was the extent of contact between different housing units. Thirty-six percent of interviewees reported having meals at the same time as people from other housing units. Thirty percent reported having recreational time at the same time as people from other housing units. Respondents also shared concerns about interacting with people from other housing units when they were transported to the medical units or to court appointments. These patterns were inconsistent with the COVID-19 PRR, which requires that detainees’ access to recreation and meal hours should be staggered to limit inter-housing interaction, which can contribute to the spread of the virus.

Finally, the PRR requires ICE to “limit transfers,” which necessarily create new contacts and points of exposure and transmission. Within this group of 50 participants, 13 were transferred to another detention facility after March 15, including three who reported symptoms. Twenty-seven people reported that when new individuals entered the detention center after March 15, they were not quarantined for two weeks before entering the general unit.

“They told us to sleep head-to-foot after they started getting lawsuits.”

51-year-old man, Yuba County Jail

23.5-Hour Daily Lockdowns Created Adverse Mental Health Impacts

In several detention centers, certain COVID-19 mitigation strategies directly violated immigrants’ rights, as lockdowns were implemented with limited communication and restrictions were placed on basic activities. Four people shared that after March 15, 2020, their movements were extremely limited, and they were at times locked in their cells for 23 to 23.5 hours a day: “They put us in cells with one other person out of fear that we would infect each other. We were kept there for 23.5 hours a day” (36-year-old man, Hudson County Correctional Center).

When lockdowns began, people received minimal information about why these changes were occurring and for how long. As one interviewee noted: “In April, they locked us in our bunkers and would bring food to our cells. They didn’t explain to us why we were not allowed to leave our bunkers anymore; they just told us that was the way it was going to be, like animals” (42-year-old woman, Eloy Detention Center).Additionally, one man held in Plymouth County Correctional Center described that during lockdown, he was not even allowed to shower, watch TV, make phone calls, or talk to other detainees.

“In April, they locked us in our bunkers and would bring food to our cells. They didn’t explain to us why we were not allowed to leave our bunkers anymore; they just told us that was the way it was going to be, like animals.”

42-year-old woman, Eloy Detention Center

In particular, the lack of social interactions and recreational activities led to people feeling isolated and created adverse mental health effects: “One could not go out to the yard, we could not do anything. You felt locked up and you would get depressed” (42-year-old woman, Eloy Detention Center and La Palma Correctional Center). These lengthy lockdowns existed in a setting where mental health conditions and concerns are highly prevalent, leading to potential exacerbations of existing issues.[60] One interviewee stated, “There were lots of suicides, people cutting their veins, hanging themselves. There were six total. They all happened in March. COVID-19 started and people became restless. My bunker was in front of ‘the hole’ and we could see how they brought out the beds with the body on it. After this started happening, they stopped letting us out of our cells and would bring us our food” (52-year-old man, Eloy Detention Center and La Palma Correctional Center).

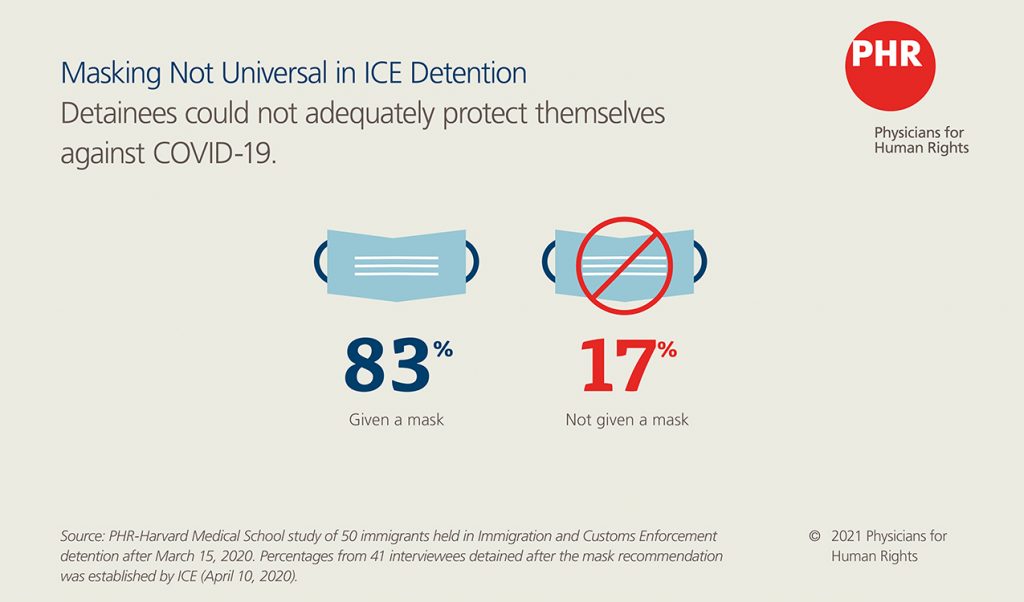

New Masks in Detention Were a Luxury

Per the COVID-19 PRR, free, washable cloth face coverings should be provided to and worn by detained individuals and staff. Specifically, the mask should “fit snugly but comfortably,” “be secured with ties or ear loops,” and “include multiple layers of fabric.”[61] Of the 41 participants who were detained after the PRR’s mask mandate was established (April 10, 2020), 83 percent (34 people) reported being given a face covering during their detention. Interviewees were given their first mask sometime between March and May 2020, depending on the facility. Of people given a mask, 59 percent (20 people) were given cloth face coverings, while 50 percent were given paper surgical masks. Even when people were given masks, it was often a one-time occurrence: of the respondents given a mask, 11 (32 percent) never had their mask replaced, 11 (32 percent) had their mask replaced once, and seven (21 percent) were given a new mask at least once a week. Five people had their mask replaced more than once, but infrequently. The quality of masks was variable, as stated by one respondent: “The mask was almost made out of old sheets with strings to tie at the back of your head. It wasn’t thick or anything. It was just a cover-up for them” (46-year-old man, Franklin County and York County Prisons).

“I had to make my own mask. I used the sleeve of one of my shirts.”

31-year-old man, Strafford County Department of Corrections

The fact that 17 percent of participants (seven people) in detention after April 10, 2020 were not given a mask indicates that even the most basic and effective mitigation strategies were not implemented at times in some detention centers. One person who never received a mask reported making his own mask, using the sleeve of one of his shirts. Another person reported that he was mocked for not having a mask by the facility staff: “Sometimes the guards, who did have face coverings, would laugh at us and be happy that we did not have facemasks” (33-year-old man in Otay Mesa Detention Center). It often took special circumstances for ICE to provide masks. Interviewees reported that masks were provided to them only after a lawsuit, immediately before a visit by a news team, or after a COVID-19 death in ICE detention.

“I have HIV, and so I asked the doctors and the staff of the detention center to … give me a face mask so that I could protect myself, as I was more vulnerable. They did not want to help me.”

33-year-old man, Otay Mesa Detention Center

Even when masks were provided, people were not consistently educated on how to use them properly. Of the 34 people given a mask, 56 percent (19 people) were told how, where, and when to use their mask. One person reported, “They just give you the mask. If you use it or not, that’s your decision (52-year-old man held in 12 different detention centers).” Mandates on when masks were supposed to be worn varied and were not clearly communicated: “There was a period of two weeks that we had to have our masks on at all times when we left our cells, but then they stopped mandating it. Perhaps because there were others that were sick” (25-year-old woman, Eloy Detention Center). The detention staff also did not lead by example, which could have exposed people to the disease: “They gave us masks every two days but no one wore them – not even the staff and security guards” (51-year-old man, Mesa Verde Detention Facility).

Four people were required to sign a waiver in order to receive a mask. One person believed the waiver absolved centers of liability (as described elsewhere[62]): “They started offering us masks in May after the big lawsuit, but they made us sign a waiver [that] in case we got sick, they wouldn’t be accountable” (27-year-old man, Tacoma Northwest Detention Center). Another person reported language barriers when signing the form: “On April 10, they gave us a mask but they made us sign a document in English, even though many of us did not speak English. The document said that if we signed, we waived the responsibility of the center if we were to get sick with COVID-19” (32-year-old man, Otay Mesa Detention Center).[63]

With No Soap, Immigrants Were Forced to Use Water Alone or Other Bath Products to Wash Their Hands

Per the most recent National Detention Standards (NDS) and the COVID-19 PRR, all facilities that house people detained by ICE are required to “replenish personal hygiene items at no cost to the detainee on an as-needed basis” (NDS) and provide individuals with “no-cost, unlimited access to supplies for hand

cleansing, including liquid soap, [and] running water” as well as “alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60 percent alcohol where permissible based on security restrictions” (PRR).[64], [65] Per the PRR, ICE does not recommend providing bar soap, but, if it is used, facilities must “ensure that it does not irritate the skin as this would discourage frequent hand washing and ensure that individuals are not sharing bars of soap.” The study’s findings show that soap was commonly unavailable to detained immigrants. Instead, people often had to rely on buying soap with their own money, washing their hands with water alone, or using other bath products to wash their hands.

“Hand soap and masks – those were like a luxury. We prayed for that in detention.”

32-year-old man, Yuba County Jail

These requirements were far from the actual lived experiences of the study participants. Forty-two percent of participants reported not having access to soap at some point during their detention: “Before [April], we would have weeks where we would not have soap…. We would request [it] but they would ignore us” (32-year-old woman, Bristol County Detention Center). When participants did have access, they were worried about the quality of the soap. One participant was concerned that “the soap was mixed with water” (39-year-old man, Bristol County Detention Center), while another was worried that “everyone used the same bar soap in the bathroom” (40-year-old man, Mesa Verde Detention Center). When soap or hand sanitizer was not available, some participants reported resorting to using shampoo to wash their hands, and one even used toothpaste.

Detainees were often forced to purchase soap with their own personal funds. Thirty-six percent of participants reported relying on purchasing soap from the commissary. Several people relied on donations from outside organizations, while others had to forgo other basic necessities to purchase soap: “Faithful Friends [a church-based organization] sent $20 per individual to buy soap in the commissary” (29-year-old man, Yuba County Jail). Another person reported: “I was working [in detention] to try to get money to call my family. I couldn’t buy bar soap…. People had to choose between buying food from the commissary or bar soap, they couldn’t afford both” (25-year-old man, Port Isabel Detention Center). Certain people with no funds to purchase soap were left without any ability to practice effective hygiene: “People who did not have money had to wash their hands only with water” (33-year-old man, Otay Mesa Detention Center). Eighteen percent of participants reported most commonly using water alone to wash their hands.

“People had to choose between buying food from the commissary or bar soap, they couldn’t afford both.”

25-year-old man, Port Isabel Detention Center

Hand sanitizer was nearly inaccessible to most participants. Eighty-two percent of people reported not having access to hand sanitizer anywhere in the detention facility. Several people reported that hand sanitizer was provided to the staff, but not to the detained population. One participant reported: “The guards have hand sanitizer in their area. But inmates can’t touch it. They’ll tell you, it’s not for us, just for them” (46-year-old man, York County Prison). Another person discussed how they were told to sanitize their hands but were never given hand sanitizer: “The fliers said we should use hand sanitizer but we didn’t have access to it and they didn’t supply it” (42-year-old woman, Eloy Detention Center).

Immigrants Disinfected Detention Facilities Themselves to Protect Against COVID-19

The NDS requires that all facilities maintain clean surfaces and fixtures and requires that sufficient cleaning equipment and supplies be made available throughout each facility.[66] In addition, per the COVID-19 PRR, facilities must “clean and disinfect surfaces and objects that are frequently touched, especially in common areas (e.g., doorknobs, light switches, sink handles, countertops, toilets, toilet handles, recreation equipment) … several times a day.” Our findings show that disinfection of facilities was inconsistent and that detainees most commonly had to clean the facilities themselves, for little or no pay. The quality of cleaning supplies, and often the lack of cleaning supplies all together, posed immense risk to the health of detained immigrants.

“We had to take on the initiative to clean the common room, especially after we found out that the sickness was getting worse. We would ask the detention center guards to give us cleaning supplies, but they didn’t.”

44-year-old woman, Adelanto ICE Processing Center

Disinfection of common areas was inconsistent and did not follow the NDS or PRR. Twenty-six percent of participants reported never observing disinfection of frequently touched surfaces in common areas (e.g. doorknobs, light switches, countertops, and recreation equipment). Of the 36 people who reported observing disinfection, only 56 percent reported seeing disinfection several times a day. The overwhelming majority (83 percent) reported that detainees disinfected the common areas themselves. Only 11 percent reported that facility staff disinfected the center.

Detainees who cleaned the common areas were often working through a voluntary employment program in the detention centers in order to secure funds for basic goods (e.g. soap, paying for telephone). Four people mentioned that they were paid $1 a day to help with cleaning (an individual bar of soap ranged from $2.29 to $3.00 in various facilities). One person raised concern around the voluntary nature of cleaning: “The detainees that did the cleaning had volunteered, they paid you a dollar a day. But it wasn’t really volunteering, they forced it upon you. I participated in cleaning the medical room” (27-year-old man, Tacoma Northwest Detention Center). Another person described how they stopped being paid once the pandemic started: “If a detainee wants to, they can help clean and are paid $1 per day to help clean. But when COVID-19 started, they didn’t pay any more and so detainees stopped cleaning with the program. Instead, everyone had to clean on their own space” (51-year-old woman, Eloy Detention Center). One person reported that staff threatened to place him in solitary confinement if he refused to clean.

Several people reported that disinfection of common areas was often self-initiated rather than mandated by ICE staff: “We had to take on the initiative to clean the common room, especially after we found out that the sickness was getting worse. We would ask the detention center guards to give us cleaning supplies, but they didn’t” (44-year-old woman, Adelanto ICE Processing Center). Another person reported: “The phones were not cleaned between people. After everyone started complaining in May, they gave us a cleaning agent and towels to clean them” (20-year-old woman, Eloy Detention Center). When detention staff did the cleaning, it was often insufficient: “They never cleaned the bathrooms or doorknobs themselves, they just sprayed Clorox on it, they never cleaned it. Then we cleaned it ourselves (32-year-old man, Yuba County Jail).”

Even when tasked to clean the common areas themselves, several detainees mentioned that they were not given enough supplies to clean properly. They reported not having “brooms or equipment … or hot water” (36-year-old man, Bergen County Jail) and having “to clean the bathrooms only with water” (24-year-old woman, Eloy Detention Center). Sometimes, people reported cleaning their dorms with the “same soap [they used] to clean [their] hands” (P28) or going “weeks without having cleaning supplies:” (24-year-old woman, Eloy Detention Center).

The potential health effects of cleaning supplies on the detained population was also concerning. One person reported that the cleaning supplies “caused many of the detainees to have respiratory issues” (32-year-old man, Otay Mesa Detention Center), while another reported that “many people started getting nosebleed from using the cleaning liquid” (27-year-old man, Tacoma Northwest Detention Center).

Detained Immigrants with Viral Symptoms Were Often Not Tested for COVID-19 or Appropriately Isolated

Participants reported a consistent lack of action by facility staff to appropriately respond to potential COVID-19 cases on the continuum from prevention to treatment. Detainees faced long wait times to see medical professionals, lack of both testing and isolation of symptomatic patients, and misuse of solitary confinement. Many facilities were non-compliant with both the 2019 NDS and the COVID-19 PRR guidelines that outline appropriate medical care, isolation of symptomatic individuals, and testing.[67]

Twenty-one out of 50 people interviewed (42 percent) experienced symptoms of COVID-19 during the pandemic, such as fever, cough, muscle aches, and loss of smell. Three out of these 21 (14 percent) never officially reported their symptoms due to fear of being sent to solitary confinement or other punishment, or anticipation of denial of medical care, because “the doctor would not come until you were very, very sick, almost at death’s door” (32-year-old man, Otay Mesa Detention Center).

“The doctor would not come until you were very, very sick, almost at death’s door.”

32-year-old man, Otay Mesa Detention Center

Out of all respondents who had reported symptoms, only 17 percent (three people) were appropriately isolated from the general population and tested for COVID-19, one of whom tested positive. The remaining 83 percent (15 people) reported their symptoms to facility staff members but did not get tested for COVID-19 and were not isolated. Common reasons that interviewees cited as to why they were not tested were: no one in the facility was able to get tested; detainees’ “symptoms were not severe enough” as perceived by staff; and staff members did not take their issues seriously because they thought the detainees were just pretending to be sick. One asymptomatic person was tested and isolated because his attorney had been exposed, but the nursing staff did not tell him what he was being tested for or why he was being tested.

Currently, ICE publicly reports the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases under isolation or monitoring. However, this number is dependent on how many potential cases are appropriately followed up with testing. The PRR, which adheres to CDC guidelines, recommends that any and all “individuals with signs or symptoms consistent with COVID-19” should be tested for COVID-19. In addition, all suspected or confirmed cases should also be “isolated[ed] … immediately in a separate environment from other individuals.” This appears to be inconsistent with the reported practices inside ICE facilities.

ICE neglected to practice even the most basic measures necessary for identifying, treating, and mitigating the spread of COVID-19 within its detention centers.

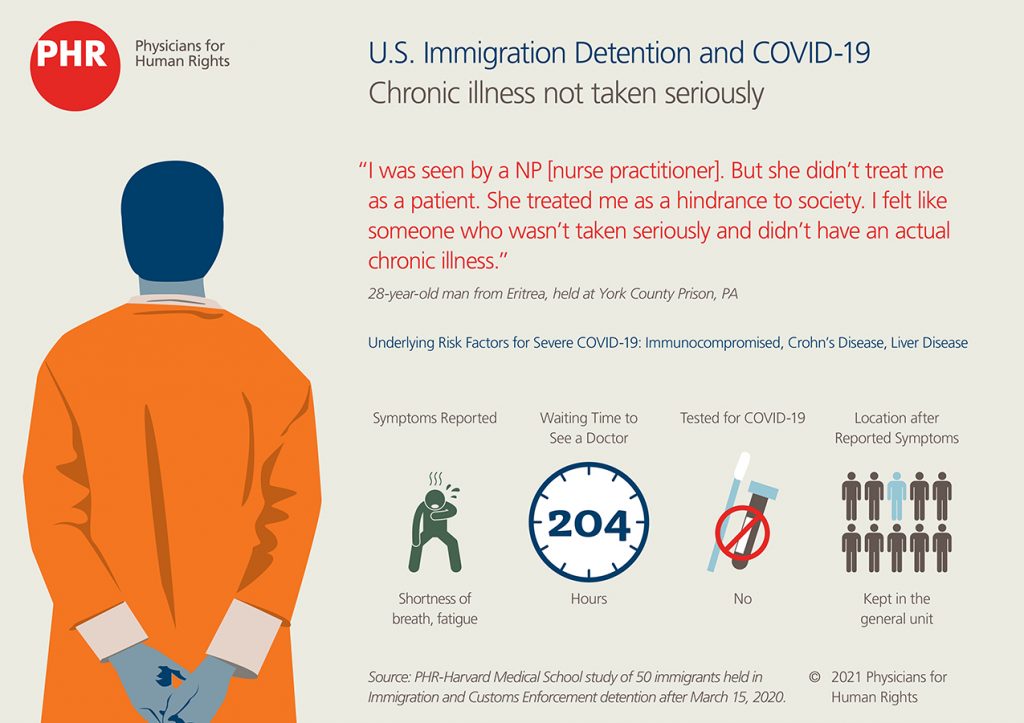

More than half of the people who reported their symptoms had their temperature checked (12 out of 18 interviewees) and were seen by a medical professional (14 out of 18 interviewees). However, long wait times and lack of isolation from the general population dramatically placed both sick people and their neighbors at risk. Interviewees reported facing prolonged wait times before being able to see a medical professional, with an average wait time of 100 hours (approximately four days). One person reported having had to wait a total of 25 days for an appointment. Importantly, two people were never seen by a medical professional at all, even after reporting their symptoms to staff members. These practices directly violate the PRR testing and isolation guidelines as well as the NDS, which state that all facilities must provide “timely responses to medical complaints” and “necessary and appropriate medical, dental and mental health care.”[68]

Although it can be difficult to ascertain the standard of care without a review of medical records, the qualitative interviews provided additional details of people’s experiences in receiving medical care. Several people were told by clinical staff that their symptoms were caused by other issues, such as influenza, bronchitis, or sinusitis, even though interviewees reported that no testing or additional exams were performed to confirm these diagnoses. One man with chronic lung disease, who was having difficulty breathing while lying down and walking, reported that the staff in the medical office “just took my temperature, they didn’t listen to my lungs or ask me questions, they didn’t even let me sit down” (41-year-old man, Stewart Detention Center). Several others reported with concern their perspective that medical staff had “done nothing” for them or fellow detainees with symptoms, or had just given them over-the-counter medication, such as ibuprofen. For example, one man with a fever was denied a coronavirus test and not isolated or given a mask; he reported, “When they found out I had a fever, they told me it was just a flu. They didn’t quarantine me, they just gave me some pills, Advil and something for my dry throat” (21-year-old man, Yuba County Jail).

Overall, these interviewee reports provide evidence that ICE neglected to practice even the most basic measures necessary for identifying, treating, and mitigating the spread of COVID-19 within its detention centers. Symptomatic people were largely kept in the general population, where they might have potentially exposed others, were rarely tested, and were threatened with solitary confinement instead of being provided adequate medical care. The graphics on pages 26, 29, 30, and 34 highlight the experiences of four respondents after they developed symptoms indicating possible COVID-19 infection and their challenges receiving medical care. These results show that, in those circumstances, ICE was not adhering to its own PRR guidelines or complying with CDC guidance on best practices to contain infectious disease outbreaks and provide timely comprehensive medical care that is mandated by the NDS and PRR guidelines.[69]

High-risk People Were Not Provided with Special Accommodation

While 88 percent (44 people) of all participants had at least one comorbidity placing them at possible increased risk of severe COVID-19, only 56 percent (28 out of 50 people interviewed) reported these risk factors to detention staff. Of the 28 people who reported their comorbidities to detention staff, only four were told that they were at high risk of having a serious illness with COVID-19. None of those four were given the option to have an individual room. One was given the option to be placed in a group of other detainees at high risk of suffering severe COVID-19.

“I sent paperwork four times to the parole office … commenting on my chronic asthma that made me high risk for COVID. I asked them if they would release me… but they simply denied me until the end, when I was found to have lung cancer.”

34-year-old man, La Palma Correctional Center

Neglect and Denial

“I am asthmatic. When there were a lot of cases in my tank [detention union], I asked to be isolated from them because I have asthma. They did not pay attention to me until May 21, 2020, nearly one month after I started reporting feeling COVID-19 symptoms. But the doctor told me that it was nothing and returned me to my unit, where I stayed seven days in bed without being able to move because I was so tired.

“They [medical staff from the detention center] then did blood tests because I felt so badly but still the doctors did not say anything more to me. It wasn’t until my asthma deteriorated and I told the doctor that I was fighting to breathe. The doctor saw me and noticed that my hand had become black and blue. She got very scared and called the ambulance. The doctor then told me that maybe I had previously had COVID-19 and that it had left me with a lot of blood clots in my lungs that now were blocking my arteries, causing my arm to lack oxygen. I reminded her that previously she had denied that I had COVID-19 and she told me that we should leave the past in the past and told me it was better to go to the emergency room.

“In the emergency room, they did some tests and saw in my lungs something that looked like cancer, so they told me they had to do more tests. Afterwards, I came back to the detention center and they isolated me. And then, the next day, an official came and told me they were going to release me … because I had cancer.”

34-year-old man held in La Palma Correctional Center

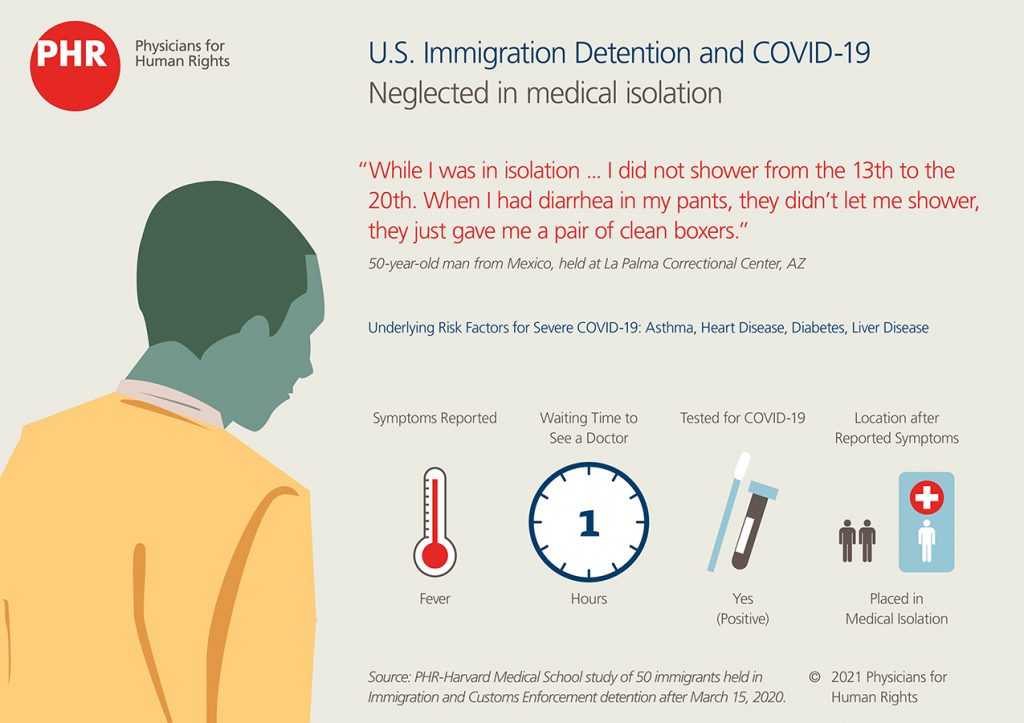

Medical Isolation Was Not Safe

Instead of appropriate medical management of symptomatic patients, interviewees were sent to solitary confinement, a practice which has been shown to potentially cause serious physical and behavioral health effects.[70] Seven people described situations which seemed to indicate misuse of solitary confinement (“the hole”), poor conditions of medical isolation, or both. Medical isolation should provide the same or greater medical and mental health care for the individual, and still allow for the isolated person to have the same rights as detainees in the general population, such as telephone contact with family, friends, and legal counsel, visitation, outdoor recreation, television, access to commissary and legal resources, nutritious food, and hygiene.[71] One person described that staff members would walk around the unit with a stretcher, and “if you were really sick, they took you to the hole” (41-year-old man, Stewart Detention Center). People who were put in medical isolation or solitary confinement lived in dehumanizing and inhumane conditions, describing “spending 12 hours with no soap, no hand sanitizer, no toilet paper … not even a mattress pad to sleep on” (31-year-old man, Hudson County Correctional Center). One person reported that, while in isolation, he didn’t have a mattress for four days and couldn’t shower for a week, even after defecating in his own underwear. Another described that, “When in isolation, you had no communication, you couldn’t even tell your family” (36-year-old man, Tacoma Northwest Detention Center). These practices created an environment of fear so that people avoided reporting symptoms: “I think I got COVID because I had body pain and felt short of breath. But I never said anything to anybody because I was so scared that they were going to punish me” (33-year-old man, Otay Mesa Detention Center).

“I think I got COVID because I had body pain and felt short of breath. But I never said anything to anybody because I was so scared that they were going to punish me.”

33-year-old man, Otay Mesa Detention Center

Detainee Complaints Led to Retaliation

Forty-three study participants (86 percent) stated that they reported and/or protested issues related to COVID-19. Those who reported or protested pandemic-related issues often did so in more than one way. For those reporting issues, reporting mechanisms included verbally complaining to staff about unsanitary conditions or lack of personal protective equipment (91 percent), filing formal grievances (42 percent), going on hunger strikes (42 percent), reporting conditions to lawyers (77 percent), reporting conditions to the media (21 percent), and sending messages to family members with the hope they would be publicized (30 percent). Four respondents also stated that they wrote letters to ICE leadership, federal and state courts, and state departments of public health.

“One person who was Mexican and transgender helped me and they punished her and put her in ‘the hole’ … for like two weeks for helping me write to the news. I was very scared that the same thing was going to happen to me.”

33-year-old man, Otay Mesa Detention Center

Of these 43 participants who reported and/or protested COVID-19 issues, 56 percent (24 people) reported experiencing acts of intimidation and retaliation after their complaints. The acts of retaliation included verbal abuse by detention facility staff (54 percent), being pepper sprayed (17 percent), being placed in solitary confinement (29 percent), and experiencing threats or actions of limiting food, communication, or commissary access (12 percent). For those who did spend time in solitary confinement after reporting or protesting, the time spent in solitary confinement ranged from a few hours to two weeks. Other forms of intimidation and retaliation described by study participants included having one’s access to the legal library and recreational areas revoked and limiting one’s access to water for hand cleaning, as well as frequent threats of pepper spray, solitary confinement, and deportation.

“We were so scared to complain sometimes. We don’t know if it will affect our case or get us more in trouble. We were scared.”

32-year-old woman, Bristol County Detention Center

Fear and Punishment

“There was a rule that they shouldn’t bring in people from other jails, but they kept bringing in people from other facilities to my unit. One time, a new person came from outside and the CO [correctional officer] tried to assign this person to my bunk, but I didn’t want to be near that person because he was sneezing all the time. I told the CO how I felt, and he started cursing at me, so I told him that if I get sick, it will be his responsibility. They sent me to the hole and didn’t even want to hear my side of the story. I was in there for one week.

“I used to be outspoken before that. I told my lawyer about what happened, and he gave me a number to call but I was scared to talk to anyone after that happened because I thought I would get punished.”

26-year-old man held in Bristol County Detention Center

Legal and Policy Framework

U.S. Government Must Ensure Health and Safety in Detention

As civil detainees, people in immigration detention are entitled to due process under the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and cannot be held in punitive conditions.[72] Under the Fifth Amendment, the government cannot put people in danger or act with deliberate indifference to a foreseeable or obvious threat.[73] The government is required to provide for the reasonable health and safety of people in detention,[74] and must take reasonable measures to prevent serious harm.[75] Courts use the standard of “deliberate [indifference] to [objectively] serious medical needs,” which the Supreme Court developed for Eighth Amendment violations of the prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment.[76]

It is difficult to ensure accountability for detention conditions. Accountability is also made difficult by the fact that ICE has deported detainees who speak out about mistreatment.

There are no detailed, legally binding standards for U.S. immigration detention center conditions, resulting in little accountability and a morass of regulations.

Detention centers are ostensibly governed by agency guidelines, such as the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) 2019 National Detention Standards. This is the pared-down Trump administration revision of the Obama administration Performance-Based National Detention Standards,[77] but its observance varies from facility to facility; as a result, it is difficult to ensure accountability for detention conditions. The 2019 National Detention Standards require that each facility maintains contingency plans in the event of an infectious disease outbreak, but these plans are not publicly accessible. Accountability is also made difficult by the fact that ICE has deported detainees who speak out about mistreatment and that stakeholder visitation is limited by the pandemic.[78]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued guidance on measures to be taken to ensure safe conditions in correctional and detention settings, but the recommendations are not specific and contain caveats for individual facilities to adapt based on their “physical space, staffing, population, operations, and other resources and conditions,” rather than insisting on a high standard of precaution.[79] Similarly, the ICE COVID-19 Pandemic Response Requirements do not go into detail about clinical care, isolation measures, and transfer to offsite care for people who test positive.[80] Medical care in ICE facilities is quite fragmented, with the federal ICE Health Service Corps providing health care in 22 out of more than 200 detention centers, while others use private contractors.[81]

The lack of detailed U.S. legislative or internal policy guidance means that, in practice, often the only resort for immigrants who face unsafe conditions of confinement is to seek constitutional protections.

The United States has signed, though not ratified, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, whose Article 12 recognizes the “enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” as a human right. Signatories are not bound to treaty obligations, but they are obligated to refrain from conduct which defeats the “object and purpose” of the treaty.[82] The UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, which apply in all detention settings, confirm that health care for people who are detained is the responsibility of the state, and that health care also must follow public health principles in regard to management of infectious disease, including treatment and clinical isolation.[83]

Solitary confinement or segregation is a harmful practice with grave health implications. Although the U.S. Supreme Court has not determined that solitary confinement is itself “cruel and unusual punishment,” it has ruled in support of procedural protections for prisoners transferred to long-term solitary confinement.[84] The UN Human Rights Committee has stated that prolonged solitary confinement in detention may constitute torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, which is prohibited under Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).[85] After extensive study of global practices, former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Juan Mendez concluded that solitary confinement should be banned in most cases and absolutely prohibited beyond 15 days, at which point it constitutes torture due to the harm inflicted by social and sensory isolation.[86] The UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners also state that prolonged solitary confinement should be absolutely prohibited.[87]

Ultimately, the government cannot inflict punishment in immigration detention because civil detention is not punitive. If conditions of confinement are poor to the point of constituting punishment,[88] remedies should include consideration of alternatives to detention and avenues for release.

International Law Limits Use of Immigrant Detention and Prohibits Criminalizing Border Crossing for Asylum Seekers

The international legal framework discourages detention of asylum seekers and immigrants except for limited purposes and as a last resort. Article 31(2) of the UN Refugee Convention permits states to restrict refugee freedom of movement only when “necessary” and only until their legal status is “regularized” or they are admitted to another country. Detention or other restrictions of movement of asylum seekers must pass the Article 31(2) necessity test, otherwise it may amount to a “penalty,” which is prohibited under the Convention.[89] The UN High Commissioner for Refugees’ (UNHCR) Executive Committee considers detention of asylum seekers as meeting the necessity test only when the government detains people to verify their identity or issue travel or identity documents, to make a preliminary assessment about their asylum claim, or based on an individualized security assessment.[90]

International law also requires states to uphold the Article 9 ICCPR standards of reasonableness, necessity, and proportionality in detention, such as notification about the reason for detention and ensuring periodic judicial review. Arbitrary and unlawful detention are prohibited by Article 9; detention is arbitrary when it reflects “elements of inappropriateness, injustice, lack of predictability and due process of law,” or fails to be reasonable, necessary, and proportional.[91]

The UN Human Rights Committee (HRC) states that beyond very brief periods, any further detention of migrants must be based on an individualized risk and security assessment, taking into full consideration alternatives to detention, such as reporting requirements or bond, and giving consideration to the impact of detention on migrants’ health.[92] The HRC has stated that detention of asylum seekers must be subject to periodic review to ensure that the detention is not arbitrary.[93] International human rights law requires governments to proactively ensure “adequate medical care during detention.”[94]

U.S. Law Flouts International Law Limitations on Immigrant Detention

International standards consider immigration detention as a last resort and require periodic hearings for all types of detention in order to prevent arbitrary detention. U.S. law requires the government to imprison several categories of immigrants without a hearing to consider if they are a risk to public safety or a flight risk.[95] The majority of people in immigration detention, however, have no criminal record,[96] and 77 percent of people released from immigration detention complied with their appearance obligations in immigration court.[97] Both of these facts are inconsistent, then, with detaining so many immigrants.

In addition to mandatory detention laws, the Trump administration short-circuited the established channels of release, such as bond and parole for asylum seekers, resulting in de facto indefinite detention.[98] A federal judge later stated that the practice of denying parole requests without justification amounted to arbitrary detention and required ICE to follow its own policy to consider parole requests.[99] Ultimately, options for release – such as release on bond if people crossed the border between ports of entry, through parole, if they entered through a port,[100] or challenging their detention before a judge[101] – are vulnerable to rollback under political pressure.

Another driving factor in the growth of immigration detention, in addition to mandatory detention laws, is the criminalization of border crossing, which violates Article 31 of the UN Refugee Convention. According to Article 31(1), refugees are not to be penalized for illegal entry, if they are fleeing persecution, “present themselves without delay,” and “show good cause.” Presence in the United States without authorization is a civil offense, but in the 1920s, nativist laws also made illegal entry[102] and reentry[103] to the United States criminal offenses.[104] These laws were increasingly prosecuted starting in the 1990s, despite evidence showing that prosecutions did not deter border crossing.[105] These prosecutions were renewed under the Zero Tolerance policy used by the Trump administration to forcibly separate families in 2018.[106]

Release from Immigration Detention is the Most Appropriate COVID-19 Remedy

During the pandemic, questions about restrictions on state use of immigration detention and standards for adequate conditions and health care have collided. When detention system medical care and public health measures during a pandemic are inadequate, as has been documented in this report, release from detention is the most appropriate and safest remedy.