The COVID-19 virus has posed a heightened threat to those in U.S. immigration custody. On Monday, June 28, at 11 a.m. EDT, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) hosted a discussion on the health and human rights implications of COVID-19 within ICE detention centers, including how the public health crisis has been handled throughout the pandemic, how vaccination has been managed for detained populations, and what needs to be done to ensure that the right to health is protected.

The conversation was moderated by Lee Gelernt, JD, MSc, a civil rights lawyer at the American Civil Liberties Union, where he serves as deputy director of the Immigrants’ Rights Project and director of the Project’s Access to the Courts Program.

Featured panelists:

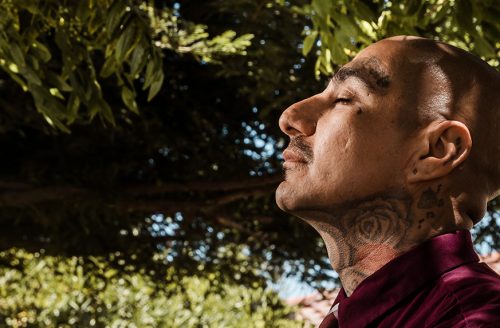

- Nilson Barahona-Marriaga is a native Honduran who immigrated to the United States more than two decades ago. In 2019, he was detained by ICE at the Irwin County Detention Center in Georgia, where he and other detained people organized a hunger strike to protest ICE’s lack of COVID-19 safety protocols and the detention of elderly people and those at high risk of contracting the disease.

- Eunice Cho, JD is senior staff attorney at the ACLU National Prison Project, where she leads the ACLU’s litigation efforts around COVID-19 in immigration detention centers.

- Josiah “Jody” Rich, MD, MPH is a professor of medicine and epidemiology at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and a practicing infectious disease and addiction specialist at The Miriam Hospital and the Rhode Island Department of Corrections. He is director and co-founder of The Center for Prisoner Health and Human Rights.

- Sophie Terp, MD, MPH is an associate professor of clinical emergency medicine at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California (USC).